Testing Provincial Welfare Generosity and Leftist Politics As Macro-Social Determinants of Population Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Report the 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The

Canadian Political Science Review Vol. 13, No. 1, 2019-20, 97-122 ISBN (online) 1911-4125 Journal homepage: https://ojs.unbc.ca/index.php/cpsr Report The 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The Solidification of an Uncompetitive Two-Party Leader-Focused System or Movement to a One-Party Predominant System? David McGrane Department of Political Studies, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan – Email address: [email protected] Tom McIntosh Department of Political Science, University of Regina James Farney Department of Political Science, University of Regina Loleen Berdahl Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan Gregory Kerr Vox Pop Labs Clifton Van Der Liden Vox Pop Labs Abstract This article closely examines campaign dynamics and voter behaviour in the 2016 Saskatchewan provincial election. Using a qualitative assessment of the events leading up to election day and data from an online vote compass gathered during the campaign period, it argues that the popularity of the incumbent Premier, Brad Wall, was the decisive factor explaining the Saskatchewan Party’s success. Résumé Ce texte examine de près les dynamiques de la campagne et le comportement des électeurs lors des élections provinciales de 2016 en Saskatchewan. On fait une évaluation qualitative des événements qui ont précédé le jour du scrutin et une analyse des données d’une boussole de vote en ligne recueillies au cours de la campagne électorale. On souligne que la popularité du premier ministre Brad Wall était le facteur décisif qui explique le succès du le Parti saskatchewannais . Key words: Saskatchewan, provincial elections, Saskatchewan Party, Brad Wall, New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan, CBC Vote Compass Mots-clés: Saskatchewan, élections provinciales, le Parti saskatchewannais, Brad Wall, le Nouveau parti démocratique de la saskatchewan David McGrane et al 98 Introduction Writing about the 2011 Saskatchewan election, McGrane et al. -

Canadian Politics

Canadian Politics Outline ● Executive (Crown) ● Legislative (Parliament) ● Judicial (Supreme Court) ● Elections ● Provinces (and Territories) Executive Crown ● Canada is a constitutional monarchy ● The Queen of Canada is the head of Canada ● These days, the Queen is largely just ceremonial – But the Governor General does have some real powers Crown ● Official title is long – In English: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. – In French: Elizabeth Deux, par la grâce de Dieu Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Défenseur de la Foi. Legislative Parliament ● Sovereign (Queen/Governor General) ● Senate (Upper House) ● House of Commons (Lower House) Sovereign ● Represented by the Governor General ● Appoints the members of Senate – On recommendation of the PM ● Duties are largely ceremonial – However, can refuse to grant royal assent – Can refuse the call for an election Senate ● 105 members ● Started as equal representation of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime region ● But, over time... – Regional equality is not observed – Nor is representation-by-population Senate ● 24 seats for each major region ● Ontario, Québec ● Maritime provinces – 10 for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, 4 for PEI ● Western provinces – 6 for each of BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba ● Newfoundland and Labrador – 6 seats ● NWT, Yukon, Nunavut – 1 seat each Senate Populate per Senator (2006) -

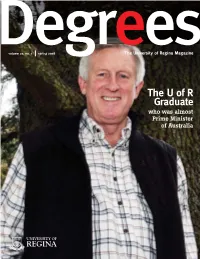

The U of R Graduate

volume 20, no. 1 spring 2008 The University of Regina Magazine TheUofR Graduate who was almost Prime Minister of Australia Luther College student Jeremy Buzash was among the competitors at the Regina Musical Club’s recital competition on May 10 in the Luther College Chapel. The competition included performances on piano, violin, flute, percussion and vocals. Up for grabs was a $1,000 scholarship. The winner was soprano Mary Joy Nelson BMus’01. Nelson graduated summa cum laude in 2006 from the vocal performance program at the University of Kentucky where she is completing a doctoral degree in voice. Photo by Trevor Hopkin, AV Services. Degrees spring 2008 1 Although you’ll find “The I read with interest your I was interested to read the Who’d have thought, after all University of Regina tribute to Professor Duncan fall 2007 article by Marie these years, that two issues in Magazine” on our front cover, Blewett in the Fall 2007 issue Powell Mendenhall on the arowofDegrees would have that moniker is not entirely of Degrees. I thought that I legacy of Duncan Blewett. I content that struck so close to accurate. That’s because in should balance the emphasis was one of a few hundred home? the truest sense Degrees is on psychoactive drug research students in his Psychology 100 I was an undergraduate your magazine. Of course we in the article with a story class in about 1969. I don’t and graduate student at the enjoy bringing you the stories about one of Professor remember what he looked like then University of of the terrific people who Blewett’s other interests. -

New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents Faculty Scholarship 4-2021 Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen - New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report Gerry Scott Judy Bradley Modeste McKenzie Craig M. Scott Brian Topp Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/reports Part of the Election Law Commons Repository Citation Scott, Gerry; Bradley, Judy; McKenzie, Modeste; Scott, Craig M.; and Topp, Brian, "Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen - New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report" (New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan, 2021). Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents. Paper 217. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/reports/217 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report April 2021 This page has been intentionally left blank. Index Introduction and Executive Summary ........................................................................page 3 Part 1: Our Results 1. Eligible voter turnout in Saskatchewan has declined .............................................page 8 2. The NDP is struggling to rebuild its caucus ...........................................................page 9 3. A regional breakdown tells a more complex story ...............................................page 10 4. Conservatives enjoy a massive fundraising advantage.........................................page 11 5. Party membership has steadily declined since its peak in 1991 ...........................page 12 Part 2: Why These Results? Political issues: 1. The so-called “Saskatchewan Party” proved to be a loyal pupil of the NDP .......page 14 2. -

Saskatchewan Elections: a History December 13Th, 1905 the Liberal Party Formed Saskatchewan’S First Elected Government

SaSkatcheWan EleCtIonS: A History DecemBer 13th, 1905 The Liberal Party formed Saskatchewan’s first elected government. The Liberals were led by Walter Scott, an MP representing the area of Saskatchewan in Wilfred Laurier’s federal government. Frederick Haultain, the former premier of the Northwest Territories, led the Provincial Rights Party. Haultain was linked to the Conservative Party and had advocated for Alberta and Saskatchewan to be one province named Buffalo. He begrudged Laurier for creating two provinces, and fought Saskatchewan’s first election by opposing federal interference in provincial areas of jurisdiction. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 25 16 52.25% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 24 9 47.47% Independent 1 - 0.28% Total Seats 25 AuguST 14th, 1908 The number of MLAs expanded to 41, reflecting the rapidly growing population. The Liberals ran 40 candidates in 41 constituencies: William Turgeon ran in both Prince Albert City and Duck Lake. He won Duck Lake but lost Prince Albert. At the time it was common for candidates to run in multiple constituencies to help ensure their election. If the candidate won in two or more constituencies, they would resign from all but one. By-elections would then be held to find representatives for the vacated constituencies. This practice is no longer allowed. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 41 27 50.79% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 40 14 47.88% Independent-Liberal 1 - 0.67% Independent 2 - 0.66% Total Seats 41 July 11th, 1912 The Provincial Rights Party morphed into the Conservative Party of Saskatchewan, and continued to campaign for expanding provincial jurisdiction. -

April 12, 2018 Hansard

SECOND SESSION - TWENTY-EIGHTH LEGISLATURE of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan ____________ DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS ____________ (HANSARD) Published under the authority of The Hon. Mark Docherty Speaker N.S. VOL. 59 NO. 41A THURSDAY, APRIL 12, 2018, 10:00 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN 2nd Session — 28th Legislature Speaker — Hon. Mark Docherty Premier — Hon. Scott Moe Leader of the Opposition — Ryan Meili Beaudry-Mellor, Hon. Tina — Regina University (SP) Lawrence, Greg — Moose Jaw Wakamow (SP) Beck, Carla — Regina Lakeview (NDP) Makowsky, Hon. Gene — Regina Gardiner Park (SP) Belanger, Buckley — Athabasca (NDP) Marit, Hon. David — Wood River (SP) Bonk, Steven — Moosomin (SP) McCall, Warren — Regina Elphinstone-Centre (NDP) Bradshaw, Fred — Carrot River Valley (SP) McMorris, Don — Indian Head-Milestone (SP) Brkich, Hon. Greg — Arm River (SP) Meili, Ryan — Saskatoon Meewasin (NDP) Buckingham, David — Saskatoon Westview (SP) Merriman, Hon. Paul — Saskatoon Silverspring-Sutherland (SP) Carr, Lori — Estevan (SP) Michelson, Warren — Moose Jaw North (SP) Chartier, Danielle — Saskatoon Riversdale (NDP) Moe, Hon. Scott — Rosthern-Shellbrook (SP) Cheveldayoff, Hon. Ken — Saskatoon Willowgrove (SP) Morgan, Hon. Don — Saskatoon Southeast (SP) Cox, Herb — The Battlefords (SP) Mowat, Vicki — Saskatoon Fairview (NDP) D’Autremont, Dan — Cannington (SP) Nerlien, Hugh — Kelvington-Wadena (SP) Dennis, Terry — Canora-Pelly (SP) Olauson, Eric — Saskatoon University (SP) Docherty, Hon. Mark — Regina Coronation Park (SP) Ottenbreit, -

Party Competition in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba

CODE POLITICS: PARTY SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT ON THE CANADIAN PRAIRIES Jared J. Wesley Department of Political Studies University of Manitoba [email protected] For Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario Please do not cite without permission. May 29, 2009 Abstract Similar in so many ways, questions persist as to why Canada’s three Prairie Provinces have developed such distinct patterns of party competition. Right-wing dynasties thrive in Alberta; Saskatchewan’s natural governing party is avowedly social democratic; while party politics in Manitoba remains relatively balanced between the forces of the right and left. This paper supplements conventional solutions to this “prairie paradox” - grounded in political culture and settlement patterns - with an ideational analysis of campaign narratives. This examination reveals that each system is focused around a unique provincial “code.” In Alberta, Social Credit and Progressive Conservative leaders have emphasized “freedom” over “security,” whereas New Democrats in Saskatchewan have stressed precisely the opposite. Successful politicians in Manitoba have steered a middling course, underscoring the importance of “moderation” in their campaign rhetoric. Cultivated by, and constraining, prominent leaders over time, these dominant discourses help explain the persistent differences between the three worlds of party competition in the region. Introduction Considering their many commonalities, the three Prairie Provinces ought to feature similar patterns of party competition. Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta are each separated by essentially artificial boundaries, their borders based on arbitrary longitudinal lines, rather than topographic or ethnic divisions (Elton, 1970). All three are associated with a common iconic landscape: one with vast stretches of prairie, bounded only by mountains to the West and the Canadian Shield to the East. -

Going Negative: Campaigning in Canadian Provinces

Canadian Political Science Review Vol. 9, No. 1, 2015, 14-27 Going Negative: Campaigning in Canadian Provinces Alex Marland Department of Political Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland – Email address: [email protected] Abstract The study of political communication in Canada’s provinces suffers from an absence of pan-Canadian information. This descriptive article bridges the gap by documenting some observable trends. It submits that negative advertising is more intense in larger provinces than in smaller jurisdictions. Permanent campaigning is the new normal as electioneering ramps up in anticipation of a fixed date election. Provincial parties and citizens avail themselves of new technology by communicating with digital video, which is not subject to the same financial, technical, content or regulatory constraints as television. Similarities of political communication across Canada are noted, including copycatting of federal-level practices. Keywords provincial politics, political communication, negative advertising, permanent campaigning, fixed date elections, new information and communication technologies, video communication. Résumé: Les études en communication politique au Canada souffrent de l’absence d’observations pancanadiennes. Cet article descriptif comble cette lacune en documentant les tendances observables. Il soutient que la publicité négative est utilisée de manière plus intensive dans les grandes provinces que dans les plus petites juridictions. La campagne permanente est devenue la nouvelle norme, alors que l’électoralisme s’accélère dans l’attente d’une élection à date fixe. Les partis provinciaux et les citoyens tirent profit des nouvelles technologies en communiquant au moyen de vidéos, lesquels ne sont pas soumis aux mêmes contraintes financières, techniques et règlementaires qu’à la télévision. Les similitudes entre les pratiques de communication politique utilisées à travers le Canada sont constatées, incluant l’imitation des pratiques au niveau fédéral. -

1 Provincial Politics Questionnaire March 2020 PQ1. BASE = ALL

1 Provincial Politics Questionnaire March 2020 PQ1. BASE = ALL SINGLE CHOICE Do you approve or disapprove of the performance of [Premier and leader of…]? [BC] Premier and NDP leader John Horgan [AB] Premier and United Conservative Party leader Jason Kenney [SK] Premier and Saskatchewan Party leader Scott Moe [MB] Premier and Progressive Conservative leader Brian Pallister [ON] Premier and Progressive Conservative leader Doug Ford [QC] Premier and Coalition Avenir Québec leader François Legault [NS] Premier and Liberal Party leader Iain Rankin [NB] Premier and Progressive Conservative leader Blaine Higgs [PEI] Premier and Progressive Conservative leader Dennis King [NL] Premier and Liberal Party leader Andrew Furey [RESPONSES] Strongly approve Moderately approve Moderately disapprove Strongly disapprove Not sure/Can’t say PQ2. Base = ALL SINGLE CHOICE GRID Do you think the current government of [PROVINCE] is doing a good job or a poor job in each of the following areas? [ROWS][RANDOMIZE] Health Care The Economy Coronavirus/COVID-19 response The Deficit/Government spending Jobs/unemployment Housing Affordability Poverty/homelessness Environment/Climate change Education Drug Use/addictions Energy - Oil & Gas/Pipelines 2 First Nations/Indigenous issues Seniors care [COLUMNS] Very good job Good job Poor job Very Poor job Not sure/Can’t say PQ3. BASE = ALL MULTI-CHOICE, MAX 3 And which of those issues would you say are the most important to you, personally. Please select up to three: [Same order as PQ2] Health Care The Economy Coronavirus/COVID-19 response The Deficit/Government spending Jobs/unemployment Housing Affordability Poverty/homelessness Environment/Climate change Education Drug Use/addictions Energy - Oil & Gas/Pipelines First Nations/Indigenous issues Seniors care PQ4. -

Saskatchewan Party Platform

We faced the pandemic - together. Then we reopened our economy - together. And now, we will build and recover - together. Our province is well positioned for a strong recovery. The Saskatchewan Party has the best plan to lead that strong recovery and the best plan to make life more affordable for everyone. Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will drive Saskatchewan’s economic recovery and cre- ate jobs. We will lower power bills for homeowners, renters, farmers and businesses. We will help with the cost of home renovations. We will build hospitals, schools, highways and other important infrastructure projects. And we will reduce taxes on small businesses. Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will make life more affordable for everyone - families, students, seniors, homeowners and others. And Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will see the provincial budget balanced by 2024. Today, Saskatchewan is much stronger than when the NDP was in government. The NDP drove people, jobs and opportunities out of Saskatchewan. They closed 52 hospitals, 176 schools, and 1200 long-term care beds for seniors. Imagine how much worse the NDP would be for our economy now. Let’s never go back to that. The Saskatchewan Party has a plan for a strong recovery and a strong Saskatchewan. It’s a plan for: A strong economy and more jobs Strong communities Strong families Building highways, schools and hospitals Making life more affordable for families, seniors and young people On Monday, October 26, join us in voting for a strong economy, a strong recovery and a strong -

Download the E-Book

THE SASKATCHEWAN ELECTION: A 2020 PERSPECTIVE ISBN 978-0-7731-0758-8 Dedicated to our colleague, Joe Garcea, whose contribution to our understanding of local, provincial and federal politics has been outstanding. Table of Contents The Co-Editors 1 Foreword – Mandates and the Eight Most Powerful Words in Politics 2 BRAD WALL, former Premier of Saskatchewan 1 The 2020 Saskatchewan Election in Context 3 KEN RASMUSSEN, University of Regina 2 Saskatchewan’s Political Parties in the 2020 Election 5 JIM FARNEY, University of Regina 3 A Campaign over Before It Began 7 MURRAY MANDRYK, Regina Leader-Post 4 The Players, the Game, and Election Narrative: Media and the 2020 SK Election 9 MERELDA FIDDLER-POTTER, University of Regina 5 Social Media and the 2020 Saskatchewan Election 11 ARJUN TREMBLAY, University of Regina ALANNA DECORBY, University of Regina 6 COVID-19 and the Saskatchewan Election 13 LOLEEN BERDAHL, University of Saskatchewan KIRSTEN SAMSON, University of Saskatchewan 7 Elections in the Time of COVID: The Economic Effects of COVID-19 on the 2020 Saskatchewan Election 15 DIONNE POEHLER, University of Toronto 8 Fiscal Anchors Aweigh 17 JASON CHILDS, University of Regina 9 A Predictable Fiscal Path during a Turbulent Time 19 HAIZHEN MOU, University of Saskatchewan 10 Federal-Provincial Issues: The Politics of Discontent 21 DALE EISLER, University of Regina 11 Leadership: Signs of the Times 23 DALE EISLER, University of Regina 12 Indigenous Issues and Governance Inclusion 25 JASON BIRD, First Nations University of Canada 13 Saskatchewan: