The Survival and Success of the CCF-NDP in Western Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Democratic Parly and Labor Political Action in Canada

^ •%0k--~* ^'i'^©fc: s $> LABOR RESEARCH REVIEW #22 The New Democratic Parly and Labor Political Action in Canada • Elaine Bernard Political humorist Barry Crimmins recently remarked that the Perot phenomenon in the last Presidential election showed the depressing state of U.S. politics. "Who would have thought/' shrugged Crimmins, "that the development of a third party would reduce political choice?" Many U.S. union progressives have envied their Canadian counterparts' success in building an enduring labor-based political party—the New Democratic Party (NDP). They look to Canada and the NDP as proof that labor and democratic socialist ideas can win a wide hearing and acceptance in North America. As U.S. activists learn about Canada's more progressive labor laws, the national system of universal publicly funded single-payer health care coverage, and the more generous and extensive entitlement programs, they naturally look to labor's political power and the role of the labor-supported New Democratic Party in winning many of these reforms and promoting progressive social change in Canada. Yet most activists in the U.S. know little about the 33-year history of the NDP, the struggles that took place within the Canadian labor movement over the party's creation, and the continuing evolution of • Elaine Bernard is the Executive Director of the Harvard Trade Union Program. Before moving to the U.S. in 1989, she was a longtime activist and the president of the British Columbia wing of the New Democratic Party of Canada. 100 Labor Research Review #21 the relationship between organized labor and the party. -

Friday, April 27, 2018

RECENT POSTINGS TO THE CANADIAN FIREARMS DIGEST [email protected] Updated: Friday, April 27, 2018 POSTS FROM CANADA HOUSE OF COMMONS FIREARMS PETITION E-1608 SCRAP BILL C-71 and devote greater resources to policing in Canada – STARTED MAY 28, 2018 • 72,113 Signatures as of April 28, 2018 12:30 pm MT https://petitions.ourcommons.ca/en/Petition/Details?Petition=e-1608 HOUSE OF COMMONS FIREARMS PETITION E-1605 AIMING LIBERALS AT THE RIGHT TARGET – STARTED MAY 28, 2018 • 1,488 Signatures as of April 28, 2018 12:30 pm MT https://dennisryoung.ca/2018/03/28/firearms-petition-e-1605-aiming-liberals-right-target/ MY CALL TO GOODALE ON BILL C-71: I WAS ANXIOUS, BUT IT WAS EASY I shared two points from my list. The staffer offered enthusiastic and courteous rebuttals. I countered. We thanked each other and said goodbye. THE GUN BLOG – APRIL 27, 2018 https://thegunblog.ca/2018/04/27/my-call-to-goodale-on-bill-c-71-i-was-anxious-but-it-was-easy/ CSSA COMMENTARY: JUSTICE MINISTER CALLS BILL C-71 A "POTENTIAL" THREAT TO YOUR CHARTER RIGHTS - A Charter Statement is prepared by the Minister to point out any potential flaws with legislation that may violate the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. From her Charter Statement on Bill C-71, under the heading Right to be secure against unreasonable search and seizure (section 8): "New subsection 58.1(1) requires the collection and retention of certain personal information in order to preserve access for possible future criminal investigations, and therefore has the potential to engage s. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Report the 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The

Canadian Political Science Review Vol. 13, No. 1, 2019-20, 97-122 ISBN (online) 1911-4125 Journal homepage: https://ojs.unbc.ca/index.php/cpsr Report The 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The Solidification of an Uncompetitive Two-Party Leader-Focused System or Movement to a One-Party Predominant System? David McGrane Department of Political Studies, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan – Email address: [email protected] Tom McIntosh Department of Political Science, University of Regina James Farney Department of Political Science, University of Regina Loleen Berdahl Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan Gregory Kerr Vox Pop Labs Clifton Van Der Liden Vox Pop Labs Abstract This article closely examines campaign dynamics and voter behaviour in the 2016 Saskatchewan provincial election. Using a qualitative assessment of the events leading up to election day and data from an online vote compass gathered during the campaign period, it argues that the popularity of the incumbent Premier, Brad Wall, was the decisive factor explaining the Saskatchewan Party’s success. Résumé Ce texte examine de près les dynamiques de la campagne et le comportement des électeurs lors des élections provinciales de 2016 en Saskatchewan. On fait une évaluation qualitative des événements qui ont précédé le jour du scrutin et une analyse des données d’une boussole de vote en ligne recueillies au cours de la campagne électorale. On souligne que la popularité du premier ministre Brad Wall était le facteur décisif qui explique le succès du le Parti saskatchewannais . Key words: Saskatchewan, provincial elections, Saskatchewan Party, Brad Wall, New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan, CBC Vote Compass Mots-clés: Saskatchewan, élections provinciales, le Parti saskatchewannais, Brad Wall, le Nouveau parti démocratique de la saskatchewan David McGrane et al 98 Introduction Writing about the 2011 Saskatchewan election, McGrane et al. -

Student Vote Results

Notley and the NDP win majority government in province-wide Student Vote Edmonton, May 5, 2015 – More than 85,000 students under the voting age cast ballots in Student Vote Alberta for the 2015 provincial election. After learning about the democratic process, researching the candidates and party platforms, and debating the future of Alberta, students cast ballots for official candidates running in their electoral division. By the end of the school day today, 792 schools had reported their election results, representing all 87 electoral divisions in the province. In total, 82,474 valid votes, 2,526 rejected ballots and 2,123 declined ballots were cast by student participants. There were many close races in the province, with 16 divisions decided by less than 25 votes. Students elected Rachel Notley and the NDP to a majority government with 56 seats, including all 19 seats in Edmonton and 15 of 25 seats in Calgary. The NDP increased their share of the popular vote to 37.1 from 12.9 per cent in 2012. Party leader Rachel Notley easily won in her electoral division of Edmonton-Strathcona with 74 per cent of the vote. The Wildrose Party won 23 seats and will form the Student Vote official opposition. The party also won 23 seats in the last Student Vote, but the party’s share of the popular vote decreased to 24.4 per cent, down from 28.2 per cent in 2012. Leader Brian Jean was defeated in his riding of Fort McMurray-Conklin by just three votes. The Progressive Conservatives took 6 seats, down from 54 in 2012 when they won a majority government. -

Engaging with Alberta Counsel: How We Can Help You

Engaging with Alberta Counsel: How we can help you About Alberta Counsel Alberta Counsel was founded after the historic 2015 Alberta election. We are a multi-partisan firm with deep roots in Alberta, specializing in government relations on a provincial and municipal level. Our staff have a wealth of concrete political experience as well as extensive educational backgrounds focused on political science, communications, public relations, government relations, law, community development and public administration. Our team has been assembled to ensure we have good rapport with the provincial government as well as with the opposition parties and other levels of government. What makes us unique • Alberta Counsel is the largest and fastest growing government relations firm in Alberta today, and the only firm who can offer a truly multi-partisan roster of staff and advisors. • Our roster of staff and advisors is unrivalled in depth of experience, networks, and professionalism. • Alberta Counsel is committed to Indigenous reconciliation and is privileged to serve many First Nations and Metis communities. • We offer cost certainty to our clients by charging a set monthly fee rather than on an hourly basis. • Alberta Counsel is the only government relations firm in Alberta that is a law firm, meaning that we are able to offer potential legal solutions to our clients in the event that lobbying efforts are not successful. Alberta Counsel’s relationship with the UCP Government Alberta Counsel’s Principals are Shayne Saskiw, a former Wildrose MLA and Official Opposition House Leader in Alberta and Jonathon Wescott, the former Executive Director of the Wildrose Party. -

Canadian Politics

Canadian Politics Outline ● Executive (Crown) ● Legislative (Parliament) ● Judicial (Supreme Court) ● Elections ● Provinces (and Territories) Executive Crown ● Canada is a constitutional monarchy ● The Queen of Canada is the head of Canada ● These days, the Queen is largely just ceremonial – But the Governor General does have some real powers Crown ● Official title is long – In English: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. – In French: Elizabeth Deux, par la grâce de Dieu Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Défenseur de la Foi. Legislative Parliament ● Sovereign (Queen/Governor General) ● Senate (Upper House) ● House of Commons (Lower House) Sovereign ● Represented by the Governor General ● Appoints the members of Senate – On recommendation of the PM ● Duties are largely ceremonial – However, can refuse to grant royal assent – Can refuse the call for an election Senate ● 105 members ● Started as equal representation of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime region ● But, over time... – Regional equality is not observed – Nor is representation-by-population Senate ● 24 seats for each major region ● Ontario, Québec ● Maritime provinces – 10 for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, 4 for PEI ● Western provinces – 6 for each of BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba ● Newfoundland and Labrador – 6 seats ● NWT, Yukon, Nunavut – 1 seat each Senate Populate per Senator (2006) -

Jason Kenney Elected Leader of UCP October 30, 2017

Jason Kenney Elected Leader of UCP October 30, 2017 JASON KENNEY ELECTED LEADER OF THE UNITED CONSERVATIVE PARTY OF ALBERTA Introduction In a victory surprising for its size and decisiveness, Jason Kenney won the leadership of the United Conservative Party of Alberta (UCP) on Saturday, October 28. Kenney took 61.1 per cent of the almost 60,000 votes cast, besting former Wildrose Party leader Brian Jean with 31.5 per cent, and 7.3 per cent for Doug Schweitzer, who managed the late Jim Prentice’s Progressive Conservative leadership campaign in 2014. Background The win capped a fifteen-month process that began when Kenney launched the idea of uniting Alberta Conservatives into one party, and is a significant tribute to his organizational skills and superior ground game. Kenney’s success had several key steps: • On July 16, 2016, he announced he would seek the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party on a platform of merging with Wildrose. • On March 18, 2017, he was elected leader of the Progressive Conservative Party with more than 75 per cent of the delegate votes. • Two months later, Kenney and Brian Jean announced a merger referendum among the membership of the PCs and Wildrose to be held on July 22. • The referendum was strongly passed by both parties by identical approvals of 96 per cent, which created the United Conservative Party and led the way to last Saturday’s leadership victory. Deep Political & Government Experience Born in Toronto and raised in Saskatchewan, Jason Kenney began his political life as a Liberal in 1988, serving as executive assistant to Ralph Goodale, then leader of the provincial Liberal Party. -

New NDP Vs. Classic NDP: Is a Synthesis Possible, and Does It Matter? Tom Langford

Labour / Le Travail ISSUE 85 (2020) ISSN: 1911-4842 REVIEW ESSAY / NOTE CRITIQUE New NDP vs. Classic NDP: Is a Synthesis Possible, and Does It Matter? Tom Langford David McGrane, The New NDP: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019) Roberta Lexier, Stephanie Bangarth & Jon Weier, eds., Party of Conscience: The CCF, the NDP, and Social Democracy in Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2018) Did you know that after Jack Layton took over as its leader in 2003, the federal New Democratic Party became as committed to the generation and dissemination of opposition research, or “oppo research,” as its major rivals in the federal party system? Indeed, the ndp takes the prize for being “the first federal party to set up stand alone websites specifically to attack opponents, now a common practice.”1 The ndp’s continuing embrace of “oppo research” as a means of challenging the credibility of its political rivals was on display during the final days of the 2019 federal election campaign. Facing a strong challenge from Green Party candidates in ridings in the southern part of Vancouver Island, the ndp circulated a flyer that attacked the Green Party for purportedly sharing “many Conservative values,” including being willing to “cut services [that] families need” and to fall short of “always defend[ing] the right to access a safe abortion.” Needless to say, the ndp’s claims were based on a very slanted interpretation of the evidence pulled together by its researchers 1. David McGrane, The New ndp: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2019), 98. -

Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As Of: September 25, 2021

Page 1 of 6 Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As of: September 25, 2021 Party Name Ballot Name Other Names Advocational International Democratic Advocational Party AID Party Party of British Columbia Advocates Advocational Democrats Advocational International Democratic Party Advocational International Democratic Party of BC Advocational Party of BC Advocational Party of British Columbia Democratic Advocates International Advocates B.C. New Republican Party Republican Party B.C. Vision B.C. Vision B.C. Vision Party BCV British Columbia Vision BC Citizens First Party BC Citizens First Party British Columbia Citizens First Party BC Ecosocialists BC Ecosocialists BC Eco-Socialists BC EcoSocialists BC Ecosocialist Alliance BC Ecosocialist Party BC First Party BC First BC Marijuana Party BC Marijuana Party British Columbia Marijuana Party Page 2 of 6 Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As of: September 25, 2021 Party Name Ballot Name Other Names BC NDP BC NDP BC New Democratic Party BC New Democrats British Columbia New Democratic Party Formerly known as: New Democratic Party of B.C. NDP New Democratic Party New Democrats BC Progressive Party Pro BC BC Progressives Progressive Party BC Refederation Party BC Refed Formerly known as: Western Independence Party Formerly known as: Western Refederation Party of BC British Columbia Action Party BC Action Party BCAP British Columbia Direct Democracy British Columbia Direct BC Direct Party Democracy Party BC Direct Democracy Party Direct Democracy British Columbia Excalibur Party BC Excalibur Party British Columbia Liberal Party BC Liberal Party British Columbia Libertarian Party Libertarian Libertarian Party of BC British Columbia Party British Columbia Party BC Party BCP British Columbia Patriot Party B.C. -

Calgary City 1988 Sept V to We

V I P Courier Systems Ltd 752 Vadorin Serge 907 4istsw 249-0675 VALENTINA HAUTE COUTURE 208 2835 23StNE 250-7900 Vadura J 266-1291 u Urton—Vallat V I P Garments Of Canada 248-4007 1822 2stsw- 244-5334 Vagabond Trailer Court Valentine A 1235 73AveSW 252-6543 V I P JANITORIAL SERVICES 37 4501 17AvSE 272-3668 Urton S 3517 49StSW 246-4655 Valentine A Elgin LTD 293-5790 Vagho R 609 1028 15AvSW 229-1193 143 llllGlenmoreTrSW 252-0595 Uruald Bradley I 524 50FrobisherBlvdSE 255-1024 V I P RESERVATIONS (1984)INC Vaheesan Ram 1263RanchviewRdNW .. 239-2578 Uruski Darreii 211QtjeenChar1ottePtaceSE 271-6758 Valentine C Peter 3012 istsw 243-5437 10Flrll22 4StSW 269-3566 Vahey Kevin 208 1431 37Stsw 249-3882 Valentine C Peter 3012 istsw 287-2255 Urvald Roy 105 2511 l7StSW 245-5425 Vaiasicca Gaetano 2124 29AvSW .... 244-0197 Urvald Steve 163-OgdenRiseSE 236-5303 V I P C 0 3230 58AVSE 279-7501 Valentine D 79VenturaRdNE 291-1374 Vaid C Bsmtl9FalwoodWyNE 280-4525 Valentine D 2848 63AveSW 249-0746 Urwin James 804 2105 90AvSW 281-4563 V J PAMENSKY CANADA INC Vaidya M 11023BraesideDrSW 252-0056 415ManitouRdSE 263-2626 Valentine David 3608 825 8AvSW.... 262-9537 Urynowicz Tadeusz i52Run<jiecaimRdNE 285-7221 Vail A E 320GlamorganPlaceSW 246-5509 Valentine E J 3408LakeCrtSW 249-8832 V J R Jewellers 4012 17AvSE 273-0552 Urysz M 264EdgebumLaneNW ... u 239-4815 Vail Doug 3715 40Stsw 246-3151 Valentine J 285-6852 Urysz Steve 2413 182SWoodviewDrSW 281-5304 V K 0 Management Ltd Vail Harold C 12WhitmanCrNE 280-3000 Valentine J 220PenbrookeWySE 235-6039 Urzada L 1908 62AveSE -

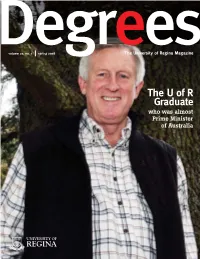

The U of R Graduate

volume 20, no. 1 spring 2008 The University of Regina Magazine TheUofR Graduate who was almost Prime Minister of Australia Luther College student Jeremy Buzash was among the competitors at the Regina Musical Club’s recital competition on May 10 in the Luther College Chapel. The competition included performances on piano, violin, flute, percussion and vocals. Up for grabs was a $1,000 scholarship. The winner was soprano Mary Joy Nelson BMus’01. Nelson graduated summa cum laude in 2006 from the vocal performance program at the University of Kentucky where she is completing a doctoral degree in voice. Photo by Trevor Hopkin, AV Services. Degrees spring 2008 1 Although you’ll find “The I read with interest your I was interested to read the Who’d have thought, after all University of Regina tribute to Professor Duncan fall 2007 article by Marie these years, that two issues in Magazine” on our front cover, Blewett in the Fall 2007 issue Powell Mendenhall on the arowofDegrees would have that moniker is not entirely of Degrees. I thought that I legacy of Duncan Blewett. I content that struck so close to accurate. That’s because in should balance the emphasis was one of a few hundred home? the truest sense Degrees is on psychoactive drug research students in his Psychology 100 I was an undergraduate your magazine. Of course we in the article with a story class in about 1969. I don’t and graduate student at the enjoy bringing you the stories about one of Professor remember what he looked like then University of of the terrific people who Blewett’s other interests.