Report the 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Sask Gazette, Part I, Apr 4, 2008

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART III (REGULATIONS)/CE NUMÉRO NE THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, APRIL 4, 2008 529 CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 104 REGINA, FRIDAY, APRIL 4, 2008/REGINA, VENDREDI, 4 AVRIL 2008 No. 14/nº 14 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’ÉTAT DES PROJETS DE LOIS (First Session,Twenty-sixth Legislative Assembly) ............................................................................................................................ 530 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ..................................................................................... 530 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS EN VIGUEUR À DES DATES PRÉCISES...................................................................... 533 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC DATES/LOIS EN VIGUEUR À DES DATES PRÉCISES ................................................... 533 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES .............................................................................................................................................. 534 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2008) ......................................................................................................................... 534 MINISTER’S ORDER/ARRÊTÉ MINISTÉRIEL ............................................................................................................................. -

HANSARD) Published Under the Authority of the Hon

THIRD SESSION - TWENTY-SEVENTH LEGISLATURE of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan ____________ DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS ____________ (HANSARD) Published under the authority of The Hon. Dan D’Autremont Speaker N.S. VOL. 56 NO. 52A WEDNESDAY, APRIL 16, 2014, 13:30 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN Speaker — Hon. Dan D’Autremont Premier — Hon. Brad Wall Leader of the Opposition — Cam Broten Name of Member Political Affiliation Constituency Belanger, Buckley NDP Athabasca Bjornerud, Bob SP Melville-Saltcoats Boyd, Hon. Bill SP Kindersley Bradshaw, Fred SP Carrot River Valley Brkich, Greg SP Arm River-Watrous Broten, Cam NDP Saskatoon Massey Place Campeau, Jennifer SP Saskatoon Fairview Chartier, Danielle NDP Saskatoon Riversdale Cheveldayoff, Hon. Ken SP Saskatoon Silver Springs Cox, Herb SP The Battlefords D’Autremont, Hon. Dan SP Cannington Docherty, Mark SP Regina Coronation Park Doherty, Hon. Kevin SP Regina Northeast Doke, Larry SP Cut Knife-Turtleford Draude, Hon. June SP Kelvington-Wadena Duncan, Hon. Dustin SP Weyburn-Big Muddy Eagles, Doreen SP Estevan Elhard, Hon. Wayne SP Cypress Hills Forbes, David NDP Saskatoon Centre Harpauer, Hon. Donna SP Humboldt Harrison, Hon. Jeremy SP Meadow Lake Hart, Glen SP Last Mountain-Touchwood Heppner, Hon. Nancy SP Martensville Hickie, Darryl SP Prince Albert Carlton Hutchinson, Bill SP Regina South Huyghebaert, D.F. (Yogi) SP Wood River Jurgens, Victoria SP Prince Albert Northcote Kirsch, Delbert SP Batoche Krawetz, Hon. Ken SP Canora-Pelly Lawrence, Greg SP Moose Jaw Wakamow Makowsky, Gene SP Regina Dewdney Marchuk, Russ SP Regina Douglas Park McCall, Warren NDP Regina Elphinstone-Centre McMillan, Hon. Tim SP Lloydminster McMorris, Hon. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Allan Blakeney: Deftly Navigating Thunderstorms

ALLAN BLAKENEY: DEFTLY NAVIGATING THUNDERSTORMS Brian Topp Saskatchewan Premier Allan Blakeney was one of Canada’s greatest premiers, and there is much for us to learn from his approach to issues ranging from managing a resource dependent economy and the Charter, to how to run a fiscally responsible, economically literate and socially progressive social democratic government. Premier ministre de la Saskatchewan, Allan Blakeney a été l’un des meilleurs chefs provinciaux du pays et aurait beaucoup à nous apprendre aujourd’hui sur la gestion d’une économie tributaire des ressources naturelles, sur la Charte des droits et libertés tout comme le fonctionnement d’un gouvernement social-démocrate qui est à la fois financièrement responsable, économiquement compétent et socialement progressiste. first met Allan Blakeney, one of Canada’s greatest pre- CEOs; constitutional issues; national unity; trade issues. It is miers, during a high-risk aeronautics experiment. not the easy problems that make it onto a premier’s desk. It I Specifically, in the 1990s the Government of is the toughest problems — and it was the very toughest Saskatchewan wanted to see what would happen when a ones that Romanow discussed with Blakeney. couple of Cessna airplanes purchased in the 1960s contin- ued to be flown as the government’s “executive air” fleet to lakeney approached each issue like a fascinating little ferry ministers and officials around the sprawling province. B chess puzzle. What if we did this? What if we did that? Would the planes stay in the air? Or would one of them Did you think of this? What would it mean if that were so? finally break up after decades of loyal service, tumbling with All with a cheerful, wry humour and the slightest undertone some of the province’s most senior people into a wheat field of skepticism about the high principles invoked by princi- 10,000 feet below? The planes spent more time being serv- pals making their cases, usually at high decibels, before the iced than they did flying — they were the last planes of their premier. -

Canadian Politics

Canadian Politics Outline ● Executive (Crown) ● Legislative (Parliament) ● Judicial (Supreme Court) ● Elections ● Provinces (and Territories) Executive Crown ● Canada is a constitutional monarchy ● The Queen of Canada is the head of Canada ● These days, the Queen is largely just ceremonial – But the Governor General does have some real powers Crown ● Official title is long – In English: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. – In French: Elizabeth Deux, par la grâce de Dieu Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Défenseur de la Foi. Legislative Parliament ● Sovereign (Queen/Governor General) ● Senate (Upper House) ● House of Commons (Lower House) Sovereign ● Represented by the Governor General ● Appoints the members of Senate – On recommendation of the PM ● Duties are largely ceremonial – However, can refuse to grant royal assent – Can refuse the call for an election Senate ● 105 members ● Started as equal representation of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime region ● But, over time... – Regional equality is not observed – Nor is representation-by-population Senate ● 24 seats for each major region ● Ontario, Québec ● Maritime provinces – 10 for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, 4 for PEI ● Western provinces – 6 for each of BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba ● Newfoundland and Labrador – 6 seats ● NWT, Yukon, Nunavut – 1 seat each Senate Populate per Senator (2006) -

Annual Report 2004-2005 Saskatchewan Justice

Annual Report 2004-2005 Saskatchewan Justice Table of Contents Letters of Transmittal . 3 Who we are . 4 2004-2005 Fiscal Year Results . 7 Results at a Glance . 7 Performance Results . 10 Financial Results – Expenditures . 36 Financial Results – Revenue . 38 Where to Obtain Additional Information . 39 Appendix A: Organizational Chart . 41 Appendix B: Boards and Commissions . 42 Appendix C: Queen’s Printer Revolving Fund and Victims Services . 46 This annual report is also available in electronic form from the Department’s web site at www.saskjustice.gov.sk.ca. 1 2 Letters of Transmittal Her Honour the Honourable Dr. Lynda M. Haverstock Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan May It Please Your Honour: I respectfully submit the Annual Report of the Department of Justice for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2005. The Honourable Frank Quennell, Q.C. Minister of Justice and Attorney General The Honourable Frank Quennell, Q.C. Minister of Justice and Attorney General Dear Sir: I have the honour of submitting the Annual Report of the Department of Justice for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2005. Doug Moen, Q.C. Deputy Minister of Justice and Deputy Attorney General 3 Who we are Vision the development and delivery of community-based justice initiatives, co-ordinates Aboriginal and The vision of Saskatchewan Justice is “A fair, northern justice initiatives and funds the Aboriginal equitable and safe society supported by a justice Courtworker program, the Police Commission and system that is trusted and understood.” the Police Complaints Investigator. It also provides provincial policing services under contract with the Mandate Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), regulates the private security industry, provides for coroners’ The mandate of Saskatchewan Justice flows from investigations, and conducts investigations of the historic and constitutional role of the Attorney residential and commercial properties being used General to uphold the rule of law1, protect basic for illegal activities. -

39 Years Conserving the River Valley

39 Years Conserving the River Valley 2 0 1 7 - 2 0 1 8 ANNUAL REPORT Message from the Today, by anyone’s measure, the Meewasin Valley Project comprised of Crown Land, and that 50% of Meewasin’s – first envisioned by master planner Raymond Moriyama Conservation Zone is outside the City of Saskatoon. Chair and Interim CEO in 1978 – has been an outstanding success when one As a result, Meewasin entered the new fiscal year sees what has been accomplished in the 67 square km April 1, 2018 with optimism. The City of Saskatoon, The 2017-2018 fiscal of the Meewasin Conservation Zone. Meewasin has although only obligated to provide Meewasin with year was challenging yet grown in its 39 years to become one of the most popular $557,000, committed $1.34 million to a $3.8 million rewarding. Meewasin was and appreciated organizations in the Saskatoon region. Meewasin status quo budget. And April 10, 2018, the created four decades Yet over time, Meewasin’s future has been of concern Government of Saskatchewan tabled a budget providing ago in 1979 by an Act as the funding provided by the statutory formula, when Meewasin with $500,000 in funding, the same amount of the Government indexed to the cost of inflation, has dropped from $36 per allocated to Meewasin by the Government in 2017. This of Saskatchewan. capita in the early 1980s to now less than $7 per capita. funding added to the city contribution and $647,000 Colin Tennent, Chair Doug Porteous, The people wanted a In response, Meewasin has had to gradually reduce its Interim CEO from the University of Saskatchewan flowed through conserved river valley, programs and services. -

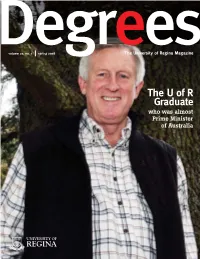

The U of R Graduate

volume 20, no. 1 spring 2008 The University of Regina Magazine TheUofR Graduate who was almost Prime Minister of Australia Luther College student Jeremy Buzash was among the competitors at the Regina Musical Club’s recital competition on May 10 in the Luther College Chapel. The competition included performances on piano, violin, flute, percussion and vocals. Up for grabs was a $1,000 scholarship. The winner was soprano Mary Joy Nelson BMus’01. Nelson graduated summa cum laude in 2006 from the vocal performance program at the University of Kentucky where she is completing a doctoral degree in voice. Photo by Trevor Hopkin, AV Services. Degrees spring 2008 1 Although you’ll find “The I read with interest your I was interested to read the Who’d have thought, after all University of Regina tribute to Professor Duncan fall 2007 article by Marie these years, that two issues in Magazine” on our front cover, Blewett in the Fall 2007 issue Powell Mendenhall on the arowofDegrees would have that moniker is not entirely of Degrees. I thought that I legacy of Duncan Blewett. I content that struck so close to accurate. That’s because in should balance the emphasis was one of a few hundred home? the truest sense Degrees is on psychoactive drug research students in his Psychology 100 I was an undergraduate your magazine. Of course we in the article with a story class in about 1969. I don’t and graduate student at the enjoy bringing you the stories about one of Professor remember what he looked like then University of of the terrific people who Blewett’s other interests. -

Issue 154 January/February 2015

the ProfessionAl eDGeissUe 154 JAnUArY/feBrUArY 2015 Profiles in Achievement Achieving a safe and Prosperous editorial provided by: martin charlton communications future through engineering and #300 - 1914 hamilton street, regina, saskatchewan s4P 3n6 Geoscience t: 306.584-1000, f: 306. 584-5111, e: [email protected] editor: lyle hewitt, Director of message, martin charlton communications e: [email protected] Design and layout: Jo Anne lauder Publishing & Design, t: 306.522-8461, e: [email protected] opinions expressed in signed contributions are those of the individual authors only, and the Association accepts no responsibility for them. the Association reserves the right to make the usual editorial changes in manuscripts professional Edge committee accepted for publication, including such revisions as are necessary to ensure correctness of grammar and robert schultz, P.eng. - chair spelling. the Association also reserves the right to refuse or withdraw acceptance from or delay publication of any manuscript. ssn 0841-6427 Deb rolfes - vice-chair Bob cochran, P.eng. - liaison councillor submissions to: Zahra Darzi, P.eng., fec The Professional Edge editorial committee marcia fortier, P.eng. 300 - 4581 Parliament Avenue, regina sK s4W 0G3 t: 306.525.9547 f: 306.525.0851 toll free: 800.500.9547 Jeanette Gelletta, engineer-in-training e: [email protected] Brett laroche, P.eng. Ken linnen, P.eng., fec material is copyright. Articles appearing in The Professional Edge may be reprinted, provided the following credit Brent marjerison, P.eng., fec is given: reprinted from The Professional Edge - Association of Professional engineers and Geoscientists of saskatchewan, (issue no.), (year). John masich, P.eng. -

New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents Faculty Scholarship 4-2021 Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen - New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report Gerry Scott Judy Bradley Modeste McKenzie Craig M. Scott Brian Topp Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/reports Part of the Election Law Commons Repository Citation Scott, Gerry; Bradley, Judy; McKenzie, Modeste; Scott, Craig M.; and Topp, Brian, "Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen - New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report" (New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan, 2021). Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents. Paper 217. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/reports/217 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commissioned Reports, Studies and Public Policy Documents by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Saskatchewan 2024: Making Change Happen New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan Election Review Panel Report April 2021 This page has been intentionally left blank. Index Introduction and Executive Summary ........................................................................page 3 Part 1: Our Results 1. Eligible voter turnout in Saskatchewan has declined .............................................page 8 2. The NDP is struggling to rebuild its caucus ...........................................................page 9 3. A regional breakdown tells a more complex story ...............................................page 10 4. Conservatives enjoy a massive fundraising advantage.........................................page 11 5. Party membership has steadily declined since its peak in 1991 ...........................page 12 Part 2: Why These Results? Political issues: 1. The so-called “Saskatchewan Party” proved to be a loyal pupil of the NDP .......page 14 2. -

April 12, 2021 Hansard

FIRST SESSION — TWENTY-NINTH LEGISLATURE of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan ____________ DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS ____________ (HANSARD) Published under the authority of The Hon. Randy Weekes Speaker N.S. VOL. 62 NO. 14A MONDAY, APRIL 12, 2021, 13:30 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN 1st Session — 29th Legislature Lieutenant Governor — His Honour the Honourable Russ Mirasty, S.O.M., M.S.M. Speaker — Hon. Randy Weekes Premier — Hon. Scott Moe Leader of the Opposition — Ryan Meili Beck, Carla — Regina Lakeview (NDP) Love, Matt — Saskatoon Eastview (NDP) Belanger, Buckley — Athabasca (NDP) Makowsky, Hon. Gene — Regina Gardiner Park (SP) Bonk, Steven — Moosomin (SP) Marit, Hon. David — Wood River (SP) Bowes, Jennifer — Saskatoon University (NDP) McLeod, Tim — Moose Jaw North (SP) Bradshaw, Hon. Fred — Carrot River Valley (SP) McMorris, Hon. Don — Indian Head-Milestone (SP) Buckingham, David — Saskatoon Westview (SP) Meili, Ryan — Saskatoon Meewasin (NDP) Carr, Hon. Lori — Estevan (SP) Merriman, Hon. Paul — Saskatoon Silverspring-Sutherland (SP) Cheveldayoff, Ken — Saskatoon Willowgrove (SP) Meyers, Derek — Regina Walsh Acres (SP) Cockrill, Jeremy — The Battlefords (SP) Moe, Hon. Scott — Rosthern-Shellbrook (SP) Conway, Meara — Regina Elphinstone-Centre (NDP) Morgan, Hon. Don — Saskatoon Southeast (SP) Dennis, Terry — Canora-Pelly (SP) Mowat, Vicki — Saskatoon Fairview (NDP) Docherty, Mark — Regina Coronation Park (SP) Nerlien, Hugh — Kelvington-Wadena (SP) Domotor, Ryan — Cut Knife-Turtleford (SP) Nippi-Albright, Betty — Saskatoon Centre (NDP) Duncan, Hon. Dustin — Weyburn-Big Muddy (SP) Ottenbreit, Greg — Yorkton (SP) Eyre, Hon. Bronwyn — Saskatoon Stonebridge-Dakota (SP) Reiter, Hon. Jim — Rosetown-Elrose (SP) Fiaz, Muhammad — Regina Pasqua (SP) Ritchie, Erika — Saskatoon Nutana (NDP) Francis, Ken — Kindersley (SP) Ross, Alana — Prince Albert Northcote (SP) Friesen, Marv — Saskatoon Riversdale (SP) Ross, Hon.