History Through Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 223 SP 007 137 TITLE Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept. of Education, Toronto. PUB LATE 67 NOTE 34p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Clothing Instruction, *Curriculum Guides, Distributive Education, *Grade 11, *Grade 12, *Hcme Economics, Interior Design, *Marketing, Merchandising, Textiles Instruction AESTRACT GRADES OR AGES: Grades 11 and 12. SUBJECT MATTER: Fashicn arts and marketing. ORGANIZATION AND PHkSTCAL APPEARANCE: The guide is divided into two main sections, one for fashion arts and one for marketing, each of which is further subdivided into sections fcr grade 11 and grade 12. Each of these subdivisions contains from three to six subject units. The guide is cffset printed and staple-todnd with a paper cover. Oi:IJECTIVE3 AND ACTIVITIES' Each unit contains a short list of objectives, a suggested time allotment, and a list of topics to he covered. There is only occasional mention of activities which can he used in studying these topics. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS: Each unit contains lists of books which relate either to the unit as a whole or to subtopics within the unit. In addition, appendixes contain a detailed list of equipment for the fashion arts course and a two-page billiography. STUDENT A. ,'SSMENT:No provision. (RT) U $ DEPARTMENT OF hEALTH EOUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF THIS DOCUMENTEOUCATION HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACT' VAS RECEIVED THE PERSON OR FROM INAnNO IT POINTSORGANIZATION ()RIG IONS STATED OF VIEW OR DO NUT OPIN REPRESENT OFFICIAL NECESSARILY CATION -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

Diana's Favorite Things

Diana’s Favorite Things By Trail End State Historic Site Curator Dana Prater; from Trail End Notes, March 2000 “Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes ... “ Although we didn’t find a blue satin sash, we recently discovered something even better. While cataloging items from the Manville Kendrick Estate collection, we had the pleasure of examining some fantastic dresses that belonged to Manville’s wife, Diana Cumming Kendrick. Fortunately for us, Diana saved many of her favorite things, and these dresses span almost sixty years of fashion history. Diana Cumming (far right) and friends, c1913 (Kendrick Collection, TESHS) Few things reveal as much about our personalities and lifestyles as our clothing, and Diana Kendrick’s clothes are no exception. There are two silk taffeta party dresses dating from around 1914-1916 and worn when Diana was a young teenager. The pink one is completely hand sewn and the rounded neckline and puffy sleeves are trimmed with beaded flowers on a net background. Pinked and ruched fabric ribbons loop completely around the very full skirt, which probably rustled delightfully when she danced. The pale green gown consists of an overdress with a shorter skirt and an underdress - almost like a slip. The skirt of the slip has the same pale green fabric and extends out from under the overskirt. Both skirt layers have a scalloped hem. A short bertha (like a stole) is attached at the back of the rounded neckline and wraps around the shoulders, repeating the scalloped motif and fastening at the front. This dress even includes a mini-bustle of stiff buckram to add fullness in the back. -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

Get a Taste of Theatre Design with Our Newest Series: the Old Globe Coloring Book! Every Thursday, We'll Post a New Page Featu

Get a taste of theatre design with our newest series: The Old Globe Coloring Book! Every Thursday, we’ll post a new page featuring an original design for costumes, sets, or props from past Globe shows. Along the way, you’ll be treated to design insight from artisans who brought these ideas to life. Color them in however you want (creativity welcome!), and post on your social media and tag @theoldglobe and #globecoloringbook. The following Tuesday, we’ll post some of our favorites, along with the designer’s original rendering and a photo of the final design onstage. It’s time for your vision to take the spotlight! Hamlet: Laertes, a young lord Dashing in a velvet cloak and cap, a richly textured houndstooth doublet (jacket) and breeches (calf length trousers). Cap is decorated with ostrich plumes, often placed on the left side of the cap leaving the right sword arm free to fight. A sword was an essential part of a gentlemen’s dress in the 17th century. Hamlet: In this 2007 production of Hamlet, the costumes were made from silk and wool fabrics in the shades of pale grey. In contrast, the main character, Hamlet, wore both a black and a scarlet suede doublet and breeches. The ladies were dressed in long sumptous gowns with corsets and padded petticoats. Sword fighting and scheming was afoot under the stars on the magical outdoor Lowell Davies Festival Stage. Familiar: Anne, eccentric aunt from Zimbabwe Costumed in grand style in a long colorful floral cotton skirt, blouse with large sleeve ruffles, and matching headdress. -

Autumn 2017 Cover

Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Front cover image: John June, 1749, print, 188 x 137mm, British Museum, London, England, 1850,1109.36. The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Managing Editor Jennifer Daley Editor Alison Fairhurst Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org i The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 ISSN 2515–0995 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2017 The Association of Dress Historians Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession number: 988749854 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer–reviewed environment. The journal is published biannually, every spring and autumn. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is distributed completely free of charge, solely for academic purposes, and not for sale or profit. The Journal of Dress History is published on an Open Access platform distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The editors of the journal encourage the cultivation of ideas for proposals. -

Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1978 Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889 Joyce Marie Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, and the Interior Design Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Joyce Marie, "Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889" (1978). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5565. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/5565 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CWTHIFG OF PIONEER WOMEN OF DAKOTA TERRI'IORY, 1861-1889 BY JOYCE MARIE LARSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Haster of Science, Najor in Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design, South Dakota State University 1978 CLO'IHING OF PIONEER WOHEU OF DAKOTA TERRITORY, 1861-1889 This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Merlene Lyman� Thlsis Adviser Date Ardyce Gilbffet, Dean Date College of �ome Economics ACKNOWLEDGEr1ENTS The author wishes to express her warm and sincere appre ciation to the entire Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design staff for their assistance and cooperation during this research. -

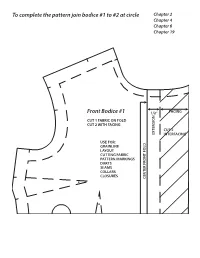

To Complete the Pattern Join Bodice #1 to #2 at Circle Front Bodice #1

To complete the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 Front Bodice #1 1/2” FACING N CUT 1 FABRIC ON FOLD CUT 2 WITH FACING CUT 2 EXTENSIO INTERFACING USE FOR: GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CLOSURES CENTER FRONT FOLD To completeTo the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle TO COMPLETE THE PATTERN JOIN BODICE #1 TO #2 AT CIRCLE STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCK FRONT BODICE #2 Front Bodice #2 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS To complete the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Back Bodice #3 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: CK SEAM GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC CK FOLD PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CENTER BA CUT HERE FOR CENTER BA To completeTo the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS Back Bodice #4 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MATCHPOINT Front Skirt #5 CUT 1 FABRIC USE FOR: V SHAPED SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED/ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM CENTER FRONT FOLD Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Front Yoke #6 CUT 1 FABRIC CUT 1 INTERFACING USE FOR: V SHAPE SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH C. F. FOLD C. F. MATCHPOINT Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MARK DART POINT HERE Back Skirt #7 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: SEAMS ZIPPERS WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM Chapter 4 CUT ON FOLD Chapter 12 Chapter 17 H TC NO WHEN