The Well Dress'd Peasant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Cloth, Fashion and Revolution 'Evocative' Garments and a Merchant's Know-How: Madame Teillard, Dressmaker at the Palais-Ro

CLOTH, FASHION AND REVOLUTION ‘EVOCATIVE’ GARMENTS AND A MERCHANT’S KNOW-HOW: MADAME TEILLARD, DRESSMAKER AT THE PALAIS-ROYAL By Professor Natacha Coquery, University of Lyon 2 (France) Revolutionary upheavals have substantial repercussions on the luxury goods sector. This is because the luxury goods market is ever-changing, highly competitive, and a source of considerable profits. Yet it is also fragile, given its close ties to fashion, to the imperative for novelty and the short-lived, and to objects or materials that act as social markers, intended for consumers from elite circles. However, this very fragility, related to fashion’s fleeting nature, can also be a strength. When we speak of fashion, we speak of inventiveness and constant innovation in materials, shapes, and colours. Thus, fashion merchants become experts in the fleeting and the novel. In his Dictionnaire universel de commerce [Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce], Savary des Bruslons assimilates ‘novelty’ and ‘fabrics’ with ‘fashion’: [Fashion] […] It is commonly said of new fabrics that delight with their colour, design or fabrication, [that they] are eagerly sought after at first, but soon give way in turn to other fabrics that have the charm of novelty.1 In the clothing trade, which best embodies fashion, talented merchants are those that successfully start new fashions and react most rapidly to new trends, which are sometimes triggered by political events. In 1763, the year in which the Treaty of Paris was signed to end the Seven Years’ War, the haberdasher Déton of Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, ‘in whose shop one finds all fashionable merchandise, invented preliminary hats, decorated on the front in the French style, and on the back in the English manner.’2 The haberdasher made a clear and clever allusion to the preliminary treaty, signed a year earlier. -

Smart Moves Smart

Page 1 Thursday s FASHION: s REVIEWS: MEDIA: The s EYE: Partying collections/fall ’09 Michael Kors, Getting ready diversity with Giorgio Narciso for the $380 quotient Armani, Rodriguez million Yves rises on Leonardo and more, Saint Laurent the New DiCaprio, the pages art auction, York Rodarte sisters 6 to 14. page 16. runways, and more, NEW page 3. page 4. YORKWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • February 19, 2009 • $3.00 WSportswear/Men’swDTHURSdAY Smart Moves It was ultrachic coming and going in Oscar de la Renta’s fall collection, a lineup that should delight his core customers. The look was decidedly dressed up, with plenty of citified polish. It was even set off by Judy Peabody hair, as shown by the duo here, wearing a tailored dress with a fur necklet and a fur vest over a striped skirt. For more on the season, see pages 6 to 14. Red-Carpet Economics: Oscars’ Party Goes On, Played in a Lower Key By Marcy Medina LOS ANGELES — From Sharon Stone to Ginnifer Goodwin, the 40-person table beneath the stone colonnade at the Chateau Marmont here was filled with Champagne-drinking stars. It appeared to be business as usual for Dior Beauty, back to host its sixth annual Oscar week dinner on Tuesday night. With the worldwide economy in turmoil, glamour lives in the run-up to Hollywood’s annual Academy Awards extravaganza on Sunday night, but brands are finding ways to save a buck: staging a cocktail party instead of a dinner, flying in fewer staffers or cutting back on or eliminating gift suites. -

I Was Tempted by a Pretty Coloured Muslin

“I was tempted by a pretty y y coloured muslin”: Jane Austen and the Art of Being Fashionable MARY HAFNER-LANEY Mary Hafner-Laney is an historic costumer. Using her thirty-plus years of trial-and-error experience, she has given presentations and workshops on how women of the past dressed to historical societies, literary groups, and costuming and re-enactment organizations. She is retired from the State of Washington . E E plucked that first leaf o ff the fig tree in the Garden of Eden and decided green was her color, women of all times and all places have been interested in fashion and in being fashionable. Jane Austen herself wrote , “I beleive Finery must have it” (23 September 1813) , and in Northanger Abbey we read that Mrs. Allen cannot begin to enjoy the delights of Bath until she “was provided with a dress of the newest fashion” (20). Whether a woman was like Jane and “so tired & ashamed of half my present stock that I even blush at the sight of the wardrobe which contains them ” (25 December 1798) or like the two Miss Beauforts in Sanditon , who required “six new Dresses each for a three days visit” (Minor Works 421), dress was a problem to be solved. There were no big-name designers with models to show o ff their creations. There was no Project Runway . There were no department stores or clothing empori - ums where one could browse for and purchase garments of the latest fashion. How did a woman achieve a stylish appearance? Just as we have Vogue , Elle and In Style magazines to keep us up to date on the most current styles, women of the Regency era had The Ladies Magazine , La Belle Assemblée , Le Beau Monde , The Gallery of Fashion , and a host of other publications (Decker) . -

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

First Review - Professional Peers - ITAA Members

DESIGN EXHIBITION COMMITTEE First Review - Professional Peers - ITAA Members Mounted Gallery Co-Chairs: Melinda Adams, University of the Incarnate Word Laura Kane, Framingham State University Su Koung An, Central Michigan University Ashley Rougeaux-Barnes, Texas Tech University Laurie Apple, University of Arkansas Lynn Blake, Lasell College Lynn Boorady, Buffalo State College Design Awards Committee: Melanie Carrico, University of North Carolina, Greensboro Review Chair: Belinda Orzado, University of Delaware Chanjuan Chen, Kent State University Kelly Cobb, University of Delaware Catalog: Sheri L. Dragoo, Texas Woman’s University Sheri Dragoo, Texas Woman’s University V.P. for Scholarship: Youn Kyung Kim, University of Tennessee Rachel Eike, Baylor University Andrea Eklund, Central Washington University Jennifer Harmon, University of Wyoming First Review Erin Irick, University of Wyoming A total of 107 pieces were accepted through the peer review Ashley Kim, SUNY Oneonta process for display in the 2017 ITAA Design Exhibition with Eundeok Kim, Florida State University a 37% acceptance rate. All jurying employed a double blind Helen Koo, Konkuk University process so the jurors had no indication of whose work they Ashley Kubley, University of Cincinnati were judging. A double-blind jury of textile and apparel peers Jung Eun Lee, Virginia Tech reviewed each submission including design statement and YoungJoo Lee, Georgia Southern University images. Further, a panel of Industry experts reviewed submissions Diane Limbaugh, Oklahoma State University -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

CO Guide to Judging Clothing

Colorado 4-H Guide for Clothing Judges Standards of Quality Clothing Construction Introduction One of our basic tasks in evaluating or judging is to be able to recognize and identify the standards that give a garment a finished, professional look. There are many techniques that can be used to accomplish the same end product. Each of us has techniques that we like and techniques that we dislike. In an objective evaluation it is essential to play down our personal preferences and to build upon identified and accepted standards. In general, there are some standards that apply to almost all techniques. Almost all construction techniques should result in an area, finish or detail that is: • Inconspicuous o Flat and smooth o Free from bulk o Stitching a uniform distance from an edge or fold • Functional • Durable –stitching uniform and secure Specific standards that can be expected in good construction are listed on the following pages. They are organized by techniques and/or areas, and the techniques are presented in alphabetical order. Overall Appearance Be objective when considering the overall appearance and appeal of a garment. It may be helpful to think about there being at least one especially pleasing feature about this garment, reflecting the many hours of though, effort and creativity that went into its construction. It may be the design, fabric, use of unusual technique or detail. Particularly neat and well-done machine or handstitching, etc. o Overall neatness and cleanliness o Plaids, stripes, checks and other designs matched at seams o Fabric with a direction in design or nap issued in garment in one direction unless garment design requires variation. -

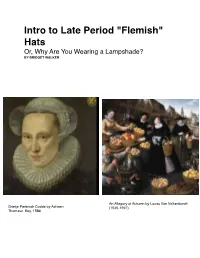

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly.