Peak Oil Demand and Long-Run Oil Prices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in the World Markets February 2020

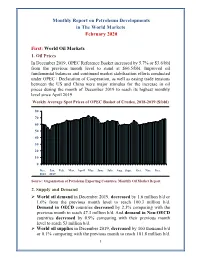

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in The World Markets February 2020 First: World Oil Markets 1. Oil Prices In December 2019, OPEC Reference Basket increased by 5.7% or $3.6/bbl from the previous month level to stand at $66.5/bbl. Improved oil fundamental balances and continued market stabilization efforts conducted under OPEC+ Declaration of Cooperation, as well as easing trade tensions between the US and China were major stimulus for the increase in oil prices during the month of December 2019 to reach its highest monthly level since April 2019. Weekly Average Spot Prices of OPEC Basket of Crudes, 2018-2019 ($/bbl) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. 2018 2019 Source: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Monthly Oil Market Report. 2. Supply and Demand World oil demand in December 2019, decreased by 1.6 million b/d or 1.6% from the previous month level to reach 100.3 million b/d. Demand in OECD countries decreased by 2.3% comparing with the previous month to reach 47.3 million b/d. And demand in Non-OECD countries decreased by 0.9% comparing with their previous month level to reach 53 million b/d. World oil supplies in December 2019, decreased by 100 thousand b/d or 0.1% comparing with the previous month to reach 101.8 million b/d. 1 Non-OPEC supplies remained stable at the same previous month level of 67.2 million b/d. Whereas preliminary estimates show that OPEC crude oil and NGLs/condensates total supplies decreased by 0.6% comparing with the previous month to reach 34.5 million b/d. -

Welcome to the 11Th Edition of Energy Perspectives! This Is An

Welcome to the 11th edition of Energy Perspectives! This is an independent report that informs Equinor’s strategy and offers a fact-based contribution to the energy transition debate. This year’s edition is an update of the edition from November last year, and with a lot happening on the global arena the last 6 months, there is a lot to consider when looking 30 years ahead. As always, this report and its data and conclusions would be impossible without the excellent work of many of my colleagues, to whom I extend my appreciation and gratitude. You are the best! 1 Covid19 is not over. In a global perspective, we are still dealing with its impact and the enormous effects it has on people, societies, economies, and markets. We are not through it yet. And we might have to live with recurring infection spikes, especially in parts of the world that do not get sufficient access to vaccines. Recurring lockdowns entailed that energy demand, and in particular oil demand due to its use as a transport fuel, was hit hard. Recovery is in the making, and faster than many feared, but oil demand, as an example, is still not back to pre-Covid19-levels. The map shows how the pandemic has affected economies across the globe, with almost all countries pink or red, that is, with negative economic development. Industrialised countries are on their way out of recession while disabling the virus, but the uncertainty is still high in many emerging economies. 2 We are seeing signs of recovery. Thanks to the development and rollout of vaccines and massive public spending to stimulate demand, there are signs that the situation is being brought under control so that we can live with the virus more like we do with normal flus. -

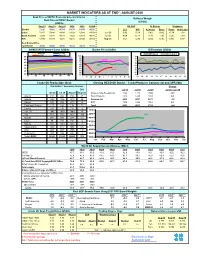

Market Indicators As at End*: August-2020

MARKET INDICATORS AS AT END*: AUGUST-2020 Spot Price of OPEC Basket & Selected Crudes Refiners' Margin Real Price of OPEC Basket (US$/b) (US$/b) Aug-18 Aug-19 Aug-20 2018 2019 2020# US Gulf N. Europe Singapore Basket 72.26 59.62 45.19 69.78 64.04 40.50 LLS WTI A. Heavy Brent Oman Arab Light Dubai 72.47 58.88 43.89 69.68 63.48 41.54 Jun-20 3.92 5.19 0.42 0.42 -0.74 1.02 North Sea Dtd 72.64 58.83 44.79 71.22 64.19 40.88 Jul-20 4.64 6.13 -1.86 1.30 1.26 1.99 WTI 67.99 54.84 42.36 65.16 57.02 38.15 Aug-20 3.67 5.30 -2.05 0.16 0.86 0.87 Real Basket Price Jun01=100 46.86 39.02 28.30 35.22 44.73 26.19 NYMEX WTI Forward Curve (US$/b) Basket Price (US$/b) Differentials (US$/b) May-20 Jun-20 WTI-Brent Brent-Dubai Jul-20 Aug-20 50 100 3 90 2 45 2018 80 1 70 40 0 60 35 2019 -1 50 30 40 -2 2020 -3 25 30 20 -4 20 10 -5 1M 3M 5M 7M 9M 11M J F M A M J J A S O N D 03 05 07 11 13 17 19 21 25 27 31 Crude Oil Production (tb/d) Closing OECD Oil Stocks - Crude/Products Commercial and SPR (Mb) Crude Oil Production (Tb/d) Production: Secondary Sources Change Diff. -

NEWS RELEASE June 15, 2021

925 North Eldridge Parkway Houston, TX 77079 Media Relations: 281-293-1149 www.conocophillips.com/media NEWS RELEASE June 15, 2021 ConocoPhillips to Host Market Update June 30 HOUSTON – ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP) will host a virtual market update on Wednesday, June 30 beginning at 9:00 a.m. Central time. The meeting will feature presentations by ConocoPhillips executives, including Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Ryan Lance. A live webcast of the meeting will be made available on the ConocoPhillips Investor Relations website, www.conocophillips.com/investor. The event will be archived and available for replay later that day. The presentation, along with a transcript, will also be available on the Investor Relations website. --- # # # --- About ConocoPhillips Headquartered in Houston, Texas, ConocoPhillips had operations and activities in 15 countries, $84 billion of total assets, and approximately 10,300 employees at March 31, 2021. Production excluding Libya averaged 1,488 MBOED for the three months ended March 31, 2021, and proved reserves were 4.5 BBOE as of Dec. 31, 2020. For more information, go to www.conocophillips.com. Contacts Media Dennis Nuss 281-293-1149 [email protected] Investor Relations 281-293-5000 [email protected] CAUTIONARY STATEMENT FOR THE PURPOSES OF THE "SAFE HARBOR" PROVISIONS OF THE PRIVATE SECURITIES LITIGATION REFORM ACT OF 1995 This news release contains forward-looking statements as defined under the federal securities laws. Forward-looking statements relate to future events and anticipated results of operations, business strategies, and other aspects of our operations or operating results. Words and phrases such as “anticipate," “estimate,” “believe,” “budget,” “continue,” “could,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict," “seek,” “should,” “will,” “would,” “expect,” “objective,” “projection,” “forecast,” “goal,” “guidance,” “outlook,” “effort,” “target” and other similar words can be used to identify forward-looking statements. -

The Economic Impact of Oil Prices by Rurik Krymm

The Economic Impact of Oil Prices by Rurik Krymm During the last three months of 1973, the tax-paid costs of typical grades of crude petroleum in the main producing areas of the world, around the Persian Gulf, were roughly quadrupled, rising for typical Iranian and Arabian Ugh t crudes from about $1.85 per barrel in September 1973 to more than $7.00 by 1 January 1974, or from approximately $13.30 to more than $50.00per ton. Since the cost of production represents an insignificantly small fraction of the new cost level (less than 2%) and subject to complex adjustments reflecting varying qualities of crude oils and advantages of geographical location, the producing countries may expect to receive a minimum average revenue of $50.00 per ton of crude oil produced on their territory instead of $12.50. If we ignore the purchases which carried the prices of relatively small amounts of oil to the $100-$ 150range, this figure of $50.00per ton with future adjustments for inflation represents a probable guide line for future cost estimates. The change affects exports of close to 1.4 billion tons of oil and consequently involves an immediate shift of financial resources of close to 60 billion dollars per year from the oil-consuming to the oil-producing countries. Tables 1, 2 and 3 give an idea of the distribution of this burden by main geographical regions and of its possible evolution over the next seven years. The figures involved are so large that comparisons have been made by some authors with the reparations proposals advanced by the Allies at the end of the First World War. -

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2019 1 Contents

2019 OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 1965 – 2019 th edition 54 Team for the preparation of the OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin Secretary General Editorial Team Chairman of the Editorial Board Head, Public Relations and Information Department Mohammad Sanusi Barkindo Hasan Hafidh Director, Research Division Editor Ayed S. Al-Qahtani Maureen MacNeill, Mathew Quinn Project Leader Coordinator, Design and Production Head, Data Services Department Carola Bayer Adedapo Odulaja Senior Production Assistant Coordinator, Statistics Team Diana Lavnick Hossein Hassani Graphic Designer Statistics Team Tara Starnegg Pantelis Christodoulides, Klaus Stöger, Mohammad Sattar, Mihni Mihnev, Justinas Pelenis, Ksenia Gutman Coordinator, IT Development Team Mohamed Mekerba IT Development Team Vedran Hrgovcic, Zairul Arifin Online Annual Statistical Bulletin 2019: asb.opec.org Download now: Smart App for OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin iOS Android Questions on data Data queries: [email protected]. Advertising The OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin now accepts advertising. For details, please contact the Head, PR and Information Department, at the following address: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Helferstorferstrasse 17, A-1010 Vienna, Austria Tel: +43 1 211 12/0 Fax: +43 1 216 43 20 Advertising: [email protected] Website: www.opec.org Photographs Courtesy OPEC. © 2019 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries ISSN 0475-0608 Contents Foreword 5 Key messages 6 Tables Page Page Section -

World Oil Outlook 2040

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 2019 World Oil Outlook 2040 2019 World Oil Outlook 2040 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Digital access to the WOO: an interactive user experience 24/7 OPEC’s World Oil Outlook (WOO) is part of the Organization’s commitment to market stability. The publication is a means to highlight and further the understanding of the many possible future challenges and opportunities for the oil industry. It is also a channel to encourage dialogue, cooperation and transparency between OPEC and other stakeholders within the industry. As part of OPEC’s ongoing efforts to improve user experience of the WOO and provide data transparency, two digital interfaces are available: the OPEC WOO App and the interactive version of the WOO. The OPEC WOO App provides increased access to the publication’s vital analysis and energy-related data. It is ideal for energy professionals, oil industry stakeholders, policymakers, market analysts, academics and the media. The App’s search engine enables users to easily find information, and its bookmarking function allows them to store and review their favourite articles. Its versatility also allows users to compare graphs and tables interactively, thereby maximizing information extraction and empowering users to undertake their own analysis. The interactive version of the WOO also provides the possibility to download specific data and information, thereby enhancing user experience. Download Access the OPEC WOO App interactive version Available for Android and iOS OPEC is a permanent, intergovernmental organization, established in Baghdad, Iraq, on 10–14 September 1960. The Organization comprises 14 Members: Algeria, Angola, Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. -

Conocophillips Completes Acquisition of Concho Resources

925 North Eldridge Parkway Houston, TX 77079-1175 Media Relations: 281-293-1149 www.conocophillips.com/media NEWS RELEASE Jan. 15, 2021 ConocoPhillips Completes Acquisition of Concho Resources HOUSTON – ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP) today announced that it has completed its acquisition of Concho Resources (“Concho”) (NYSE: CXO) following approval by shareholders of both companies. “We appreciate the strong support for this transaction from the shareholders of both companies, which we view as further affirmation of the significant benefits it will deliver,” said Ryan Lance, ConocoPhillips chairman and chief executive officer. “This acquisition results in the combination of two premier companies that can lead the structural change for our vital industry that’s critical to investors. We expect the company to deliver differential performance on three key mandates: providing affordable energy to the world, generating superior returns on and of capital and demonstrating ESG leadership.” Lance added, “I also welcome Tim Leach to ConocoPhillips’ board of directors and executive leadership team. Tim and his organization built a best-in-class Permian company and we both look forward to creating significant value from this transaction. Thanks to the considerable efforts of our transition teams over these past few months, we’re off to a fast start toward seamlessly integrating our two companies and building momentum as a sector leader.” ConocoPhillips and Concho will each file the vote results for their respective special shareholder meetings on a Form 8-K with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In accordance with the terms of the merger agreement, each share of Concho common stock was converted into the right to receive 1.46 shares of ConocoPhillips common stock at the effective time of the merger. -

Oil Production Capacity Expansion

Third OPEC International Seminar OPEC in a New Energy Era: Challenges and Opportunities 12-13 September 2006,Vienna, Austria Oil Production Capacity Expansion HE Dr Chakib KHELIL, Minister of Energy and Mines, Algeria Outline I. Prospects for Oil Demand & Supply II. OPEC Upstream Capacity Expansion Plans III. NOC/IOC Co-operation IV. Concluding Remarks 1 I. Oil Demand & Supply World Primary Energy Demand Million toe Source: OPEC 2 I. Oil Demand & Supply Conventional & Non-Conventional Oil Resource Conventional oil: Non-Conventional Oil: ~6-8 Trillion barrels of oil in place ~7 Trillion barrels of oil in place Remaining Tar Sands Recoverable Tar Sands Produced OilOil ShalesShales && BitumenBitumen 38%38% 39%39% Enhanced ExtraExtra Oil Recovery Heavy Oil Target Heavy Oil 23%23% Challenge : Challenge : Improved recovery technologies Cost-effective extraction technologies needed needed Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2004 3 I. Oil Demand & Supply Proved Reserves vs. Non-OPEC Supply Growth Proved (Oil) Reserves Non-OPEC Supply Growth Billion barrels Year on Year Changes (mb/d) 1200 2,000 1,500 900 1,000 500 600 0 OPEC 300 -500 FSU FSU Non-OPEC Ex FSU -1,000 Non-OPEC 0 -1,500 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Est Est Source: BP 4 I. Oil Demand & Supply Increase in Demand Met by OPEC 1,000 b/d 2500 2300 1900 2000 1500 1400 1500 1100 1100 1000 800 800 500 400 500 300 0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 -500 -500 -1000 -1500 -1400 -1600 -2000 NB: Figures include crude oil, condensates and NGL’s Source: IEA 5 II. -

2019 World Oil Outlook 2040 Executive Summary

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 2019 World Oil Outlook 2040 Executive Summary Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 2019 World Oil Outlook 2040 Executive Summary Digital Access to the WOO: an interactive user experience 24/7 OPEC’s World Oil Outlook (WOO) is part of the Organization’s commitment to market stability. The publication is a means to highlight and further the understanding of the many possible future challenges and opportunities for the oil industry. It is also a channel to encourage dialogue, cooperation and transparency between OPEC and other stakeholders within the industry. As part of OPEC’s ongoing efforts to improve user experience of the WOO and provide data transparency, two digital interfaces are available: the OPEC WOO App and the interactive version of the WOO. The OPEC WOO App provides increased access to the publication’s vital analysis and energy-related data. It is ideal for energy professionals, oil industry stakeholders, policymakers, market analysts, academics and the media. The App’s search engine enables users to easily find information, and its bookmarking function allows them to store and review their favourite articles. Its versatility also allows users to compare graphs and tables interactively, thereby maximizing information extraction and empowering users to undertake their own analysis. The interactive version of the WOO also provides the possibility to download specific data and information, thereby enhancing user experience. Download Access the OPEC WOO App interactive version Available for Android and iOS OPEC is a permanent, intergovernmental organization, established in Baghdad, Iraq, on 10–14 September 1960. The Organization comprises 14 Members: Algeria, Angola, Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. -

August 2020 OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 12 August 2020 Feature article: Crude and product price movements Oil market highlights i Feature article iii Crude oil price movements 1 Commodity markets 6 World economy 9 World oil demand 24 World oil supply 35 Product markets and refinery operations 52 Tanker market 58 Crude and refined products trade 61 Commercial stock movements 66 Balance of supply and demand 71 Chairman of the Editorial Board HE Mohammad Sanusi Barkindo Secretary General Editor-in-Chief Dr. Ayed S. Al-Qahtani Director, Research Division email: aalqahtani(at)opec.org Editor Behrooz Baikalizadeh Head, Petroleum Studies Department email: bbaikalizadeh(at)opec.org Contributors Crude Oil Price Movements Yacine Sariahmed Oil Price Analyst, PSD email: ysariahmed(at)opec.org Commodity Markets Hector Hurtado Financial Analyst, PSD email: hhurtado(at)opec.org World Economy Imad Al-Khayyat Chief Economic Analyst, PSD email: ial-khayyat(at)opec.org Dr. Asmaa Yaseen Modelling & Forecasting Analyst, PSD email: ayaseen(at)opec.org Dr. Joerg Spitzy Senior Research Analyst, PSD email: jspitzy(at)opec.org World Oil Demand Hassan Balfakeih Chief Oil Demand Analyst, PSD email: hbalfakeih(at)opec.org World Oil Supply Mohammad Ali Danesh Chief Oil Supply Analyst, PSD email: mdanesh(at)opec.org Product Markets and Refinery Operations Tona Ndamba Senior Refinery & Products Analyst, PSD email: tndamba(at)opec.org Tanker Markets Douglas Linton Senior Research Specialist, PSD email: dlinton(at)opec.org Crude and Refined Products Trade Douglas Linton Senior Research Specialist, PSD email: dlinton(at)opec.org Stock Movements Dr. Aziz Yahyai Senior Research Analyst, PSD email: ayahyai(at)opec.org Technical Team Nadir Guerer Senior Research Analyst, DRDO email: nguerer(at)opec.org Dr. -

Non-OPEC Production Outages

Table 3b. Non-OPEC Petroleum and Other Liquids Production (million barrels per day) U.S. Energy Information Administration | Short-Term Energy Outlook - September 2021 2020 2021 2022 Year Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 2020 2021 2022 North America ....................................................... 27.97 24.28 25.14 25.73 25.18 26.41 26.25 26.83 27.09 27.46 27.90 28.20 25.78 26.17 27.67 Canada .................................................................... 5.64 4.90 4.94 5.54 5.63 5.41 5.64 5.81 5.84 5.81 5.83 5.86 5.26 5.62 5.83 Mexico ..................................................................... 2.00 1.94 1.91 1.90 1.93 1.95 1.86 1.90 1.88 1.84 1.81 1.77 1.94 1.91 1.82 United States ........................................................... 20.33 17.44 18.29 18.29 17.62 19.05 18.76 19.12 19.38 19.81 20.26 20.58 18.58 18.64 20.01 Central and South America ................................. 6.01 6.05 6.63 5.89 5.61 6.26 6.93 6.62 6.10 6.82 7.36 7.01 6.15 6.36 6.83 Argentina ................................................................. 0.69 0.60 0.64 0.62 0.63 0.67 0.70 0.69 0.71 0.72 0.75 0.73 0.64 0.67 0.73 Brazil ....................................................................... 3.44 3.89 4.29 3.52 3.23 3.90 4.46 4.14 3.53 4.36 4.75 4.28 3.79 3.94 4.23 Colombia .................................................................