Rajkumar, Nidhi. “Justice Equals Dharma: a Comparative Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kriya-Yoga" in the Youpi-Sutra

ON THE "KRIYA-YOGA" IN THE YOUPI-SUTRA By Shingen TAKAGI The Yogasutra (YS.) defines that yoga is suppression of the activity of mind in its beginning. The Yogabhasya (YBh.) by Vyasa, the oldest (1) commentary on this sutra says "yoga is concentration (samadhi)". Now- here in the sutra itself yoga is not used as a synonym of samadhi. On the other hand, Nyayasutra (NS.) 4, 2, 38 says of "the practice of a spe- cial kind of concentration" in connection with realizing the cognition of truth, and also NS. 4, 2, 42 says that the practice of yoga should be done in a quiet places such as forest, a natural cave, or river side. According NS. 4, 2, 46, the atman can be purified through abstention (yama), obser- vance (niyama), through yoga and the means of internal exercise. It can be surmised that the author of NS. also used the two terms samadhi and yoga as synonyms, since it speaks of a special kind of concentration on one hand, and practice of yoga on the other. In the Nyayabhasya (NBh. ed. NS. 4, 2, 46), the author says that the method of interior exercise should be understood by the Yogasastra, enumerating austerity (tapas), regulation of breath (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), contem- plation (dhyana) and fixed-attention (dharana). He gives the practice of yoga (yogacara) as another method. It seems, through NS. 4, 2, 46 as mentioned above, that Vatsyayana regarded yama, niyama, tapas, prana- yama, pratyahara, dhyana, dharana and yogacara as the eight aids to the yoga. -

Universal Mythology: Stories

Universal Mythology: Stories That Circle The World Lydia L. This installation is about mythology and the commonalities that occur between cultures across the world. According to folklorist Alan Dundes, myths are sacred narratives that explain the evolution of the world and humanity. He defines the sacred narratives as “a story that serves to define the fundamental worldview of a culture by explaining aspects of the natural world, and delineating the psychological and social practices and ideals of a society.” Stories explain how and why the world works and I want to understand the connections in these distant mythologies by exploring their existence and theories that surround them. This painting illustrates the connection between separate cultures through their polytheistic mythologies. It features twelve deities, each from a different mythology/religion. By including these gods, I have allowed for a diversified group of cultures while highlighting characters whose traits consistently appear in many mythologies. It has the Celtic supreme god, Dagda; the Norse trickster god, Loki; the Japanese moon god, Tsukuyomi; the Aztec sun god, Huitzilopochtli; the Incan nature goddess, Pachamama; the Egyptian water goddess, Tefnut; the Polynesian fire goddess, Mahuika; the Inuit hunting goddess, Arnakuagsak; the Greek fate goddesses, the Moirai: Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos; the Yoruba love goddess, Oshun; the Chinese war god, Chiyou; and the Hindu death god, Yama. The painting was made with acrylic paint on mirror. Connection is an important element in my art, and I incorporate this by using the mirror to bring the audience into the piece, allowing them to see their reflection within the parting of the clouds, whilst viewing the piece. -

Yudhishthira's Wisdom Is an Ancient Story

Yudhishthira's wisdom is an ancient story. Which is a part of Mahabharata, Indian greatest epic? Or it simply says a journey of five brothers in the jungle. Four levels parts for this text Literal comprehension, interpretation, critical thinking/ analysis, and assimilation are: Yudhishthira's wisdom Source: Mahabharata BBA|BBA-BI|BBA-TT|BHCM|BHM|BCIS|BHM Literal comprehension of this story The story ' Yudhishthira's wisdom ' has been taken from the greatest epic 'Mahabharata'. Once upon a time five Pandavas brother's were wondering in a forest to hunt a deer. But the deer in their sight disappeared suddenly. In the min time, they felt tiredness grew thirsty & they were unable to move ahead. They set under a tree & Yudhisthira's sent his eldest brother Sahadeva. To search for water but he didn't come for a long time. He sent his entire brother's one after the other gradually. However, none of them returned for a long time. Therefore, ultimately Yudhisthira's himself set out in search of his bother's following their footprints. After a short walk, he notices a beautiful pool. On its bank, his four brother's were lying either unconsciousness or death. Although viewing the events he was in stream distress & sorrow. Then he bent to drink water from the pool but an unknown voice warned him. Not to drink water from the pool before answering his questions. After listening carefully Yudhisthira's tactfully answered all questions of Yama(the god of justice & death). His four brothers were prostrate on the ground due to their disobedience to the voice of Yama. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Puranas Also Talk About This Deed, Again Equating Garuda with Syena (Sanskrit Word for Eagle)

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Garuda – the divine Vahana of Vishnu Copyright © 2012, DollsofIndia Namah pannaganaddhaaya vaikunta vasavardhineh | Sruti-sindhu Sudhothpaada-mandaraaya Garutmathe || "I bow to Garuda, the One with the beautiful wings, whose limbs are adorned by the mighty serpents, who he has conquered in battle. I bow to the One who is forever in the devotion of his Lord, Vishnu. He is as adept as the Mandara Mountain, in churning the ocean of the Vedas, capturing the very essence of their wisdom." - the first two lines of the Garuda Stotra Garuda, the Mighty Eagle The Garuda is a large, mythical Eagle, which appears prominently in both Hindu and Buddhist mythology. Incidentally, Garuda is also the Hindu name for the constellation Aquila. The Brahminy kite and Phoenix are considered to be the modern representations of Garuda. Garuda is the national symbol of Indonesia – this mighty creature is depicted as a large Javanese eagle. 0In Hinduism, Garuda is an Upadevata, a divine entity, and is depicted as the vahana or mount of Sri Maha Vishnu. Garuda is usually portrayed as being a strong man; having a golden, glowing body; with a white face, red wings, and an eagle's beak. He is adorned with a crown on his head. This very ancient deity is believed to have a gigantic form, large enough to block out the Surya Devata or the Sun God. Garuda is widely known to be a permanent and sworn enemy of the Nagas, the ones belonging to the serpent race - it is believed that Garuda fed only on snakes. -

A Comprehensive Guide by Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts

A Comprehensive Guide By Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts: Mahabharata ● Written by Vyasa ● Its plot centers on the power struggle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes. They fight the Kurukshetra War for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. ● As per legend, Vyasa dictates it to Ganesha, who writes it down ● Divided into 18 parvas and 100 subparvas ● The Mahabharata is told in the form of a frame tale. Janamejaya, an ancestor of the Pandavas, is told the tale of his ancestors while he is performing a snake sacrifice ● The Genealogy of the Kuru clan ○ King Shantanu is an ancestor of Kuru and is the first king mentioned ○ He marries the goddess Ganga and has the son Bhishma ○ He then wishes to marry Satyavati, the daughter of a fisherman ○ However, Satyavati’s father will only let her marry Shantanu on one condition: Shantanu must promise that any sons of Satyavati will rule Hastinapura ○ To help his father be able to marry Satyavati, Bhishma renounces his claim to the throne and takes a vow of celibacy ○ Satyavati had married Parashara and had a son with him, Vyasa ○ Now she marries Shantanu and has another two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya ○ Shantanu dies, and Chitrangada becomes king ○ Chitrangada lives a short and uneventful life, and then dies, making Vichitravirya king ○ The King of Kasi puts his three daughters up for marriage (A swayamvara), but he does not invite Vichitravirya as a possible suitor ○ Bhishma, to arrange a marriage for Vichitravirya, abducts the three daughters of Kasi: Amba, -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

A Compact Biography of Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami

**¸ÉÒMÉÖ¯û& ¶É®úhɨÉÂ** A compact biography of Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami. First Edition: June 2006. A compact biography Publishers: of Shashwat Prakashan Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati 206, Amrut Cottage, near Diwanman Sai Temple (Tembe) Sw āmi. Manikpur VASAI ROAD (W) Dist. Thane 401202 Phone: 0250-2343663. Copyright: Dr. Vasudeo V. Deshmukh, Pune By Compose: Dr. Vasudeo V. Deshmukh. www.shrivasudevanandsaraswati.com Printers: Shri Dilipbhai Panchal SUPR FINE ART, Mumbai. Phone 022-24944259. Price: Rs. 250.00 Publishers Shashwat Prakashan, Vasai. This book is sponsored by P.P. Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami Maharaj Prabodhini. ii Dedicated to the Sacred Memory of My Master ā ā ā The picture of Shri Sw mi Mah r ja on the cover page displays the lyrical garland (H ārabandha) composed by P.P. Shri Dixita Sw āmi in his praise. ˜Ìâ¨ÌÉ Fâò¨ÌÉ ²ÌÙ¨ÌÉ—ÌÙÉ —ÌÙ¥ÌÌ¥Ì̷̥Éþ ˜ÌÌœú·Éþ œúvÌœúvÌÉ* ¥ÌÉzâù ¬ÌÕzâù¥Ìzâù¥ÌÉ ²ÌOÌÙsÌOÌÙûœúOÌÙÉû ¬ÌÕFòœÉú FÉò`ÌFÉò`ÌÉ** M®¿aÆ K®¿aÆ Su¿ambhuÆ BhuvanavanavahaÆ M¡rahaÆ RatnaratnaÆ. Vand® ár¢d®vad®vaÆ Sagu¸agururaguruÆ ár¢karaÆ KaµjakaµjaÆ.. Yogir āja Vja V āmanrao D. Gu½ava¸¢ Mah¡r¡ja iii iv The scheme of transliteration. Blessings of P. Pujya Shri Narayan Kaka Maharaj Dhekane. + +Ì < <Ê = >ð @ñ Añ ीगणेशदतगु यो नमः। Paramahans Parivr ājak āch ārya Shri V āsudevananda a ¡ i ¢ u £ ¤ ¥ Saraswati (Tembe) Swami Maharaj is widely believed to be the incarnation of Lord Datt ātreya. In his rather brief life of 60 years, 24 of D Dâ +Ìâ +Ìæ +É +: them as an itinerant monk, he revived not only the Datta tradition but also the Vedic religion as expounded in the Smritis and Pur ānās. -

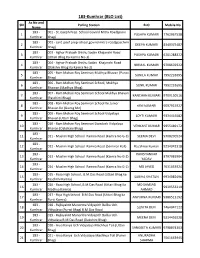

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep. School Govind Mitra Road(purvi 1 PUSHPA KUMARI 7762067538 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 002 - sant josef prep school,govind mitra road(paschimi 2 DEEPA KUMARI 8340375487 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 003 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 3 PUSHPA KUMARI 6201288322 Kumhrar (Uttari Bhag Ka Kamra No-3) 183 - 004 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 4 NIRMAL KUMARI 9708602922 Kumhrar (Dakshni Bhag Ka Kamra No-2) 183 - 005 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Mukhya Bhavan (Purwi 5 SUNILA KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhag) 183 - 006 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School, Mukhya 6 SUNIL KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhawan (Madhya Bhag) 183 - 007 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Mukhya Bhavan 7 KANCHAN KUMARI 9709150516 Kumhrar (Paschimi Bhag) 183 - 008 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Ke Junior 8 rANI kUMARI 9097915927 Kumhrar Bhavan Ke (Gairag Me) 183 - 009 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Vidyalaya 9 JOYTI KUMARI 9334416582 Kumhrar Bhavan (Uttari Bhag) 183 - 010 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Dwadash Vidyalaya 10 VENKANT KUMAR 9955489172 Kumhrar Bhavan (Dakshani Bhag) 183 - 11 011 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-3) SEEMA DEVI 9708200524 Kumhrar 183 - 12 012 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Seminar Hall) Raj Shree Kumari 9234342318 Kumhrar 183 - RAVISHANKAR 13 013 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-2) 8797983904 Kumhrar YADAV 183 - 14 014 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-1) MD JAVED 7631653924 Kumhrar 183 - 015 - Raza High School , B.M.Das Road (Uttari -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: