Home Truths: Women Writing Science in the Nuclear Dawn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

Judith Merril's Expatriate Narrative, 1968-1972 by Jolene Mccann a Thesis Submi

"The Love Token of a Token Immigrant": Judith Merril's Expatriate Narrative, 1968-1972 by Jolene McCann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2006 © Jolene McCann, 2006 Abstract Judith Merril was an internationally acclaimed science fiction (sf) writer and editor who expatriated from the United States to Canada in November 1968 with the core of what would become the Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy in Toronto. Merril chronicled her transition from a nominal American or "token immigrant" to an authentic Canadian immigrant in personal documents and a memoir, Better to Have Loved: the Life of Judith Merril (2002). I argue that Sidonie Smith's travel writing theory, in particular, her notion of the "expatriate narrative" elucidates Merril's transition from a 'token' immigrant to a representative token of the American immigrant community residing in Toronto during the 1960s and 1970s. I further argue that Judith Merril's expatriate narrative links this personal transition to the simultaneous development of her science fiction library from its formation at Rochdale College to its donation by Merril in 1970 as a special branch of the Toronto Public Library (TPL). For twenty-seven years after Merril's expatriation from the United States, the Spaced Out Library cum Merril Collection - her love-token to the city and the universe - moored Merril politically and intellectually in Toronto. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dianne Newell for introducing me to the Merril Collection and sharing her extensive collection of primary sources on science fiction and copies of Merril's correspondence with me, as well as for making my visit to the Merril Collection at the Library and Archives of Canada, Ottawa possible. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

THYME FIVE THYME Is Edited and Published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic

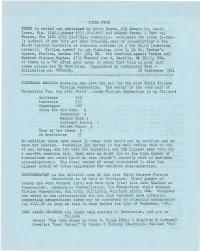

THYME FIVE THYME is edited and published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic. 3141,(phones (03) 26-1966) and Andrew Brown, 5 York St, Prahan, Vic 318-1 (03) 51-7702), Australia. Available for trade (1-for- lj 2-for-l if you both get your fanzine), news or subscriptions 6 for -£2.00 (.within Australia or overseas surface) or 3 for tf2.00, (overseas airmail). British agents Joseph Nicholas, Boom 9, 94 St. George’s Square, Pimlico, London SW1Y 3QY, UK. Nth American agents Teresa and Patrick Nielsen Hayden, 4712 Fremont Ave N, Seattle, WA 98.IO3, USA. If there is a *X* after your name, i.t means that thia is your last' isaue unless-, you Do Something. Registered by Australian Post - publication no. VBH2625. 28 September 1981 AUSTRALIA LOOSES: Austalia has lost the bid for the 41st World Science Fiction Convention. The result of the vote held at Denvention Two, the 39th World lienee Fiction Convention is as follows: Baltimore . 916 Australia 523 Copenhagen 188 Write In: New York 5 Johnstown 4 Medlow Bath 1 Rottnest Isalnd 1 Palnet Sharo 1 None of the Above 3 No Rreference 37 In addition there were about 30 votes that could not be verified and so were not counted. Australia did better in the mail voting than in the at con voting, and the vote for Australia was the highest ever vote for a non-Nth American bid. Both were no doubt due to the high number of Australians who voted (most of whom wouldn’t normally vote in worldcon site-selection). -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc. -

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: to Be Announced

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: To be announced Course Description The label “social science fiction,” initially coined by Isaac Asimov in 1953 as a broad category to describe narratives focusing on the effects of novel technologies and scientific advances on society, became a pejorative leveled at a new group of authors that rose to prominence during the sixties and seventies. These writers, who became associated with “New Wave” science fiction movement, differentiated themselves from their predecessors by consciously turning their backs on the pulpy adventure stories and tales of technological optimism of their predecessors in order to produce experimental, literary fiction. Rather than concerning themselves with “hard” science, social science fiction written by authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Samuel Delany focused on speculative societies (whether dystopian, alien, futuristic, etc.) and their effects on individual characters. In this junior tutorial you’ll receive a crash course in the groundbreaking science fiction of the sixties and seventies (with a few brief excursions to the eighties and nineties) through various mediums, including the experimental short stories, landmark novels, and innovative films that characterize the period. Responding to the social and political upheavals they were experiencing, each of our authors leverages particular sub-genres of science fiction to provide a pointed critique of their contemporary society. During the first eight weeks of the course, as a complement to the social science fiction we’ll be reading, students will familiarize themselves with various theoretical and critical methods that approach literature as a reflection of the social institutions from which it originates, including Marxist literary critique, queer theory, feminism, critical race theory, and postmodernism. -

GOTHIC HORROR Gothic Horror a Reader's Guide from Poe to King and Beyond

GOTHIC HORROR Gothic Horror A Reader's Guide from Poe to King and Beyond Edited by Clive Bloom Editorial matter and selection © Clive Bloom 1998 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. __ First published 1998 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-0-333-68398-9 ISBN 978-1-349-26398-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-26398-1 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 __ Published in the United States of America 1998 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. -

A Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association in This Issue

294 Fall 2010 Editors Karen Hellekson SFRA 16 Rolling Rdg. A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Jay, ME 04239 Review [email protected] [email protected] Craig Jacobsen English Department Mesa Community College 1833 West Southern Ave. Mesa, AZ 85202 [email protected] In This Issue [email protected] SFRA Review Business Managing Editor Out With the Old, In With the New 2 Janice M. Bogstad SFRA Business McIntyre Library-CD University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Thanks and Congratulations 2 105 Garfield Ave. 101s and Features Now Available on Website 3 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 SFRA Election Results 4 [email protected] SFRA 2011: Poland 4 Nonfiction Editor Features Ed McKnight Feminist SF 101 4 113 Cannon Lane Research Trip to Georgia Tech’s SF Collection 8 Taylors, SC 29687 [email protected] Nonfiction Reviews The Business of $cience Fiction 9 Fiction Editor Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick 9 Edward Carmien Fiction Reviews 29 Sterling Rd. Directive 51 10 Princeton, NJ 08540 Omnitopia Dawn 11 [email protected] The Passage: A Novel 12 Media Editor Dust 14 Ritch Calvin Gateways 14 16A Erland Rd. The Stainless Steel Rat Returns 15 Stony Brook, NY 11790-1114 [email protected] Media Reviews The SFRA Review (ISSN 1068- I’m Here 16 395X) is published four times a year by Alice 17 the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA), and distributed to SFRA members. Splice 18 Individual issues are not for sale; however, Star Trek: The Key Collection 19 all issues after 256 are published to SFRA’s Website (http://www.sfra.org/) no fewer than The Trial 20 10 weeks after paper publication. -

Sol Rising Issue

Special Worldcon Issue $2.50 Free for members. Want to become a member? SOL RISING Check out the back page for more info. The Newsletter of The Friends of the Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy SOL RISING Friends of the Merril Collection Number 29,August 2003 Inside Articles 1 My Residency 7 Inside the Merril Guestbook Columns 2 View from the Chair 3 From the Collection Head 5 So Bad They’re Good There’s always something interesting going on at the Merril, from readings by world famous Info Bits authors to our annual Pulps show and sale. Photos by Andrew Specht. 3 Events 3 Special Thanks 3 Worldcon Notes My Residency 6 Volunteers Needed! 8 Membership and By: Robert J. Sawyer Renewal n April, May, and June of 2003, I was writer-in-residence at the Merril Collection. Many people have thanked me for my generosity in doing this- Iso let’s start by setting the record straight. It was a paying job, funded by the Reach Us Toronto Public Library and the Friends of the Library’s South Region. They’re Friends of the Merril Collection, the heroes of this, and I am extremely grateful for their support. c/o Lillian H.Smith Branch, TPL, My residency began with a reception for library board members and staff at 239 College St. 3rd Floor, Toronto, the Toronto Reference Library, with refreshments provided by the Friends of the Ontario, M5T-1R5 Merril Collection (thank you!). At that event, I said that being writer-in-resi- www.tpl.toronto.on.ca/merril/home.htm dence at the Merril is “an honour without parallel” for an author of science fic- www.friendsofmerril.org/ tion. -

7.2 10Th Anniversary •Fi Part

INDEX Michael Winkler p. 2 Editorial p. 3 Al Purdy p. 4 Fernando Aguiar p. 7 Judith Merril p. 8 Albuquerque Mendes p. 12 bill bissett p. 13 Brigitta Bali p. 13 Dave Godfrey p. 14 Opal Louis Nations p. 17 James Gray p. 18 Karl Jirgens p. 20 Roland Sabatier p. 23 Rafael Barreto-Rivera p. 24 Frank Davey p. 25 Yves Troendle p. 26 / John Feckner p. 28 Doug Back/Hu Hohn/Norman White p. 30 "A" Battery "A" Group p. 32 Steven Smith p. 36 Nicholas Power p. 37 Ray DiPalma p. 38 Marina LaPalma p. 39 Kathy Fretwell p. 39 Raymond Souster p. 40 Robert Clayton Casto p. 42 John Donlan p. 43 Don Summerhayes p. 44 Merlin Homer p. 44 David UU p. 46 Jones p. 47 Elaine L. Corts p. 47 Gerry Gilbert p. 48 Libby Scheier p. 50 W. Mark Sutherland p. 51 Cola Franzen/Fernando de Rojas p. 52 Denis Vanier p. 53 Alain-Arthur Painchaud p. 54 Beverley Daurio p. 55 Monty Cantsin p. 56 Abigail Simmons p. 57 Kevin Connolly p. 58 George Bowering p. 63 bpNichol p. 64 Lola Lemire Tostevin p. 66 Huguette Turcotte p. 71 jwcurry p. 72 Books in Review p. 78 Contributors' Notes p. 80 Guillermo Deis/er p. 80 , Editorial I Editorial Process. A sinusoidal wave. Processus. Une vague sinusolilale. Welcome to the second Bienvenue a la deuxieme expression manifestation of our tenth du numero de notre dixieme anniversary issue. Rampike anniversaire. Rampike a vu le jour en initiated publication in 1979 and 1979, et est apparu dans les kiosques a appeared on the news/ands for journaux pour la premiere f ois en the first time in 1980. -

The Latest Issue of F&SF

Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELET And Madly Teach LLOYD BIGGLE, JR. 4 SHORT STORIES Three For Carnival JOHN SHEPLEY 32 The Colony MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 48 Breakaway House RON GOULART 61 Flattop GREG BENFORD 71 The Third Dragon ED M. CLINTON 100 Man of Parts H. L. GOLD 117 ARTICLE H. P. Lovecraft: The House and the Shadows J. VERNON SHEA 82 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 39 Books JUDITH MERRIL and FRITZ LEIBER 40 Beamed Power THEODORE L. THOMAS 70 Science: Time and Tide ISAAC ASIMOV 106 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by Mel Hunter (see page 116) Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Eduoard L. Ferman, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR Dale Beardalt, CIRCULATION MANAGER The Magazine of Fafltasy aftd Scitflct Fiction, Volume 30, No. 5, Whole No. 180, Ma;, 1966. Published monthly by Mercury Preu, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Annual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and tht Pan American Uniofl, $6.00 in all other countries. PublicatioN office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. H. 03302. Editorial and general mail should be sent to 347 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Clau postage paid at Concord, N. H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1966 by Mercury Preu, Inc. All rights including translatioou onto other languages,_ reservtd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, sel/·addreued nvelo;es; tlu rublishw .usumts no responsibilil' for return of Uftsolicited manuscripts. A college sophomore, applying for a summer ;ob, was asked to give the names of two professors as references.