A Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors a Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 In This Issue [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business Big Issue, Big Plans 2 SFRA Business Craig Jacobsen Looking Forward 2 English Department SFRA News 2 Mesa Community College Mary Kay Bray Award Introduction 6 1833 West Southern Ave. Mary Kay Bray Award Acceptance 6 Mesa, AZ 85202 Graduate Student Paper Award Introduction 6 [email protected] Graduate Student Paper Award Acceptance 7 [email protected] Pioneer Award Introduction 7 Pioneer Award Acceptance 7 Thomas D. Clareson Award Introduction 8 Managing Editor Thomas D. Clareson Award Acceptance 9 Janice M. Bogstad Pilgrim Award Introduction 10 McIntyre Library-CD Imagination Space: A Thank-You Letter to the SFRA 10 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Book Reviews Heinlein’s Children 12 105 Garfield Ave. A Critical History of “Doctor Who” on Television 1 4 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 One Earth, One People 16 [email protected] SciFi in the Mind’s Eye 16 Dreams and Nightmares 17 Nonfiction Editor “Lilith” in a New Light 18 Cylons in America 19 Ed McKnight Serenity Found 19 113 Cannon Lane Pretend We’re Dead 21 Taylors, SC 29687 The Influence of Imagination 22 [email protected] Superheroes and Gods 22 Fiction Book Reviews SFWA European Hall of Fame 23 Fiction Editor Queen of Candesce and Pirate Sun 25 Edward Carmien The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories 26 29 Sterling Rd. Nano Comes to Clifford Falls: And Other Stories 27 Princeton, NJ 08540 Future Americas 28 [email protected] Stretto 29 Saturn’s Children 30 The Golden Volcano 31 Media Editor The Stone Gods 32 Ritch Calvin Null-A Continuum and Firstborn 33 16A Erland Rd. -

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Science Fiction English 2071G (650) Winter 2018

Department of English & Writing Studies Speculative Fiction: Science Fiction English 2071G (650) Winter 2018 Instructor: Alyssa MacLean Weekly online review session: Email: [email protected] Tues 1:45-2:45 (please log in using the Tel: (519) 661-2111 ext. 87416 Blackboard Collaborate tool on OWL) Office: AHB 1G33 In-person Office Hours: Wed 11:00- 12:30, Thurs 10:30-12:00, and by appointment Antirequisites/Prerequisites: None COURSE DESCRIPTION: Science fiction is a speculative art form that deals with new technologies, faraway worlds, and disruptions in the possibilities of the world as we know it. However, it is also very much a product of its time—a literature of social criticism that is anchored in a specific social and historical context. This course will introduce students to the genre of science fiction, starting with three highly influential works from the nineteenth and early twentieth century—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine and Wells’s The War of the Worlds—that are preoccupied with humanity’s place in an inhospitable universe. Next, we examine Walter Miller’s novel A Canticle For Leibowitz, a Cold War novel that reflects both the apocalyptic sensibility of the era of nuclear confrontation in the sixties and the feelings of historical inevitability that marked the era. Building on these important precedents, our next texts use discussions of alien species and alternative futures to explore the nature of human identity. Ursula Le Guin’s novel The Left Hand of Darkness uses the trope of alien contact to explore the possibilities of an androgynous society unmarked by the divisions of gender. -

FILE 770:38 2 Editorial Rambling Science Fiction Writer Mack Reynolds Died of Cancer January 31, According to Rick Katze

t YE OLDE COLOPHON FILE 770 is edited by Mike Glyer, at 5828 Woodman Ave. #2, Van Nuys CA 91401. This newzine serving science fiction fandom is published less often than Charlie Brown recommends, and more often than Andrew Porter can keep count (see item else where this issue), but to be more specific, shows up about every six weeks. While F77O can be obtained for hot news, sizzling rumors (printable or not), arranged trades with clubzines and newzines, and expensive Inng-distance phone calls (not collect), subscriptions are most highly prized. Rates: 5/$3 (US) will get your issues sent first-class in North America, and printed matter overseas. $1 per issue covers air printed matter mailing overseas. Direct those expensive, long-distance calls to (213) 787-5061. I’m never home Tuesday nights, so don’t kill yourselves trying to reach me then. I do have a message machine, if it comes down to that... Want back issues? Send request for info. Thanks for production help last issue to: Anne Hansen, Fran Smith, Dean Bell, Debbie Ledesma.______________________ ______ ROUNDMGS mihe glyer ~ — ORIENTATION FOR NEW READERS : Why is this fanzine titled FILE 770? Late in ‘■"z 1977, when I was nerving up to start a fannish newzine to succeed KARASS, I found it difficult to find a title that had not been previously used. I looked through dictionaries, and the Thesaurus. I scanned Bruce Pelz’ voluminous fanzine index. I declined offers to revive titles like FANAC and STARSPINKLE. It became my contention that all the good sf story references usable as newzine titles had been taken. -

Other Worldly Words 2019

Other Worldly Words 2019 Thursday, January 31st at 6:45 pm What the Hell Did I Just Read: A Novel of Cosmic Horror by David Wong While investigating a fairly straightforward case of a shape-shifting interdimensional child predator, Dave, John and Amy realized there might actually be something weird going on. Thursday, February 28th at 6:45 pm The Collapsing Empire by John Scalzi An empire of star systems, connected by an extradimensional conduit called the Flow, is threatened by eventual extinction as it appears to be breaking down. Thursday, March 28th at 6:45 pm The City of Brass by S.A. Chakraborty On the streets of eighteenth-century Cairo, Nahri is a con woman of unsurpassed skill. She makes her living swindling Ottoman nobles, hoping to one day earn enough to change her fortunes. Thursday, April 25th at 6:45 pm Jade City by Fonda Lee Jade is the lifeblood of the island of Kekon. It has been mined, traded, stolen, and killed for -- and for centuries, honorable Green Bone warriors like the Kaul family have used it to enhance their magical abilities and defend the island from foreign invasion. Thursday, May 30th at 6:45 pm Foundryside by Robert Jackson Bennett In a city that runs on industrialized magic, a secret war will be fought to overwrite reality itself. Thursday, June 27th at 6:45 pm Tales of the Dying Earth by Jack Vance As a swollen red sun grows ever closer to annihilating the Earth, decadent magicians compete for the technology of an ancient age — a science now known as magic. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Full Celebration Overview

Center for the Study of Women in Society For Immediate Release Website: http://csws.uoregon.edu/ [email protected] 541-346-5077 “Celebrating Forty Years: Anniversary Event to Showcase Feminist Research, Activism, and Creativity” Eugene, OR – This fall, the Center for the Study of Women in Society (CSWS) celebrates the legacy of feminist research, teaching, activism, and creativity at the University of Oregon. Presented in collaboration with the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies and ASUO Women’s Center, CSWS’s 40th Anniversary Celebration will be held Nov. 7-9, 2013, in UO’s Erb Memorial Union. Free and open to the public (ticketing required), the event offers multiple opportunities to witness the long reach of feminist thought and production through engaging narratives about our past, present, and possible futures. On Thursday, Nov. 7, 3-6:30 p.m., the celebration kicks off with the premiere of Agents of Change, a documentary that chronicles the development of the Center for the Study of Women in Society, from its origins in the women’s movement to Fortune magazine editor William Harris’ gift that endowed it to the present moment Among the special guest speakers will be Eugene Mayor Kitty Piercy on women and leadership. On Friday, Nov. 8, 9 a.m.-5 p.m., the “Women’s Stories, Women’s Lives” Symposium explores four decades of feminist research and activism through the personal narratives, visual illustrations, and dialogue of more than twenty women activists, professionals, scholars, and community leaders. Among the symposium panelists, local activist Kate Barkley will talk about domestic violence and the creation of Womenspace in the 1970s, Eugene Mayor Kitty Piercy will lend insight into issues of reproductive rights in the 1980s, Eugene Weekly owner Anita Johnson will offer how changing legislation affected workplace equity in the 1990s, and Mobility International co-founder Susan Sygall will provide insight into women and the disability movement in the new millennium. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

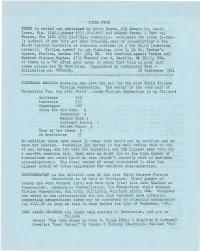

THYME FIVE THYME Is Edited and Published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic

THYME FIVE THYME is edited and published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic. 3141,(phones (03) 26-1966) and Andrew Brown, 5 York St, Prahan, Vic 318-1 (03) 51-7702), Australia. Available for trade (1-for- lj 2-for-l if you both get your fanzine), news or subscriptions 6 for -£2.00 (.within Australia or overseas surface) or 3 for tf2.00, (overseas airmail). British agents Joseph Nicholas, Boom 9, 94 St. George’s Square, Pimlico, London SW1Y 3QY, UK. Nth American agents Teresa and Patrick Nielsen Hayden, 4712 Fremont Ave N, Seattle, WA 98.IO3, USA. If there is a *X* after your name, i.t means that thia is your last' isaue unless-, you Do Something. Registered by Australian Post - publication no. VBH2625. 28 September 1981 AUSTRALIA LOOSES: Austalia has lost the bid for the 41st World Science Fiction Convention. The result of the vote held at Denvention Two, the 39th World lienee Fiction Convention is as follows: Baltimore . 916 Australia 523 Copenhagen 188 Write In: New York 5 Johnstown 4 Medlow Bath 1 Rottnest Isalnd 1 Palnet Sharo 1 None of the Above 3 No Rreference 37 In addition there were about 30 votes that could not be verified and so were not counted. Australia did better in the mail voting than in the at con voting, and the vote for Australia was the highest ever vote for a non-Nth American bid. Both were no doubt due to the high number of Australians who voted (most of whom wouldn’t normally vote in worldcon site-selection).