For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fan Cultures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FAN CULTURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Hills | 256 pages | 01 Mar 2002 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415240253 | English | London, United Kingdom Fan Cultures PDF Book In America, the fandom also began as an offshoot of science fiction fandom, with fans bringing imported copies of Japanese manga to conventions. Rather than submitting a work of fan fiction to a zine where, if accepted, it would be photocopied along with other works and sent out to a mailing list, modern fans can post their works online. Those who fall victim to the irrational appeals are manipulated by mass media to essentially display irrational loyalties to an aspect of pop culture. Harris, Cheryl, and Alison Alexander. She addresses her interests in American cultural and social thought through her works. In doing so, they create spaces where they can critique prescriptive ideas of gender, sexuality, and other norms promoted in part by the media industry. Stanfill, Mel. Cresskill, N. In his first book Fan Cultures , Hills outlines a number of contradictions inherent in fan communities such as the necessity for and resistance towards consumerism, the complicated factors associated with hierarchy, and the search for authenticity among several different types of fandom. Therefore, fans must perpetually occupy a space in which they carve out their own unique identity, separate from conventional consumerism but also bolster their credibility with particular collectors items. They rose to stardom separately on their own merits -- Pickford with her beauty, tumbling curls, and winning combination of feisty determination and girlish sweetness, and Fairbanks with his glowing optimism and athletic stunts. Gifs or gif sets can be used to create non-canon scenarios mixing actual content or adding in related content. -

Asimov on Science Fiction

Asimov On Science Fiction Avon Books, 1981. Paperback Table of Contents and Index Table of Contents Essay Titles : I. Science Fiction in General 1. My Own View 2. Extraordinary Voyages 3. The Name of Our Field 4. The Universe of Science Fiction 5. Adventure! II. The Writing of Science Fiction 1. Hints 2. By No Means Vulgar 3. Learning Device 4. It’s A Funny Thing 5. The Mosaic and the Plate Glass 6. The Scientist as Villain 7. The Vocabulary of Science Fiction 8. Try to Write! III. The Predictions of Science Fiction 1. How Easy to See The Future! 2. The Dreams of Science Fiction IV. The History of Science Fiction 1. The Prescientific Universe 2. Science Fiction and Society 3. Science Fiction, 1938 4. How Science Fiction Became Big Business 5. The Boom in Science Fiction 6. Golden Age Ahead 7. Beyond Our Brain 8. The Myth of the Machine 9. Science Fiction From the Soviet Union 10. More Science Fiction From the Soviet Union Isaac Asimov on Science Fiction Visit The Thunder Child at thethunderchild.com V. Science Fiction Writers 1. The First Science Fiction Novel 2. The First Science Fiction Writer 3. The Hole in the Middle 4. The Science Fiction Breakthrough 5. Big, Big, Big 6. The Campbell Touch 7. Reminiscences of Peg 8. Horace 9. The Second Nova 10. Ray Bradbury 11. Arthur C. Clarke 12. The Dean of Science Fiction 13. The Brotherhood of Science Fiction VI Science Fiction Fans 1. Our Conventions 2. The Hugos 3. Anniversaries 4. The Letter Column 5. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

2 the Cultural Economy of Fandom JOHN FISKE

2 The Cultural Economy of Fandom JOHN FISKE Fandom is a common feature of popular culture in industrial societies. It selects from the repertoire of mass-produced and mass-distributed entertainment certain performers, narratives or genres and takes them into the culture of a self-selected fraction of the people. They are then reworked into an intensely pleasurable, intensely signifying popular culture that is both similar to, yet significantly different from, the culture of more ‘normal’ popular audiences. Fandom is typically associated with cultural forms that the dominant value system denigrates – pop music, romance novels, comics, Hollywood mass-appeal stars (sport, probably because of its appeal to masculinity, is an exception). It is thus associated with the cultural tastes of subordinated formations of the people, particularly with those disempowered by any combination of gender, age, class and race. All popular audiences engage in varying degrees of semiotic productivity, producing meanings and pleasures that pertain to their social situation out of the products of the culture industries. But fans often turn this semiotic productivity into some form of textual production that can circulate among – and thus help to define – the fan community. Fans create a fan culture with its own systems of production and distribution that forms what I shall call a ‘shadow cultural economy’ that lies outside that of the cultural industries yet shares features with them which more normal popular culture lacks. In this essay I wish to use and develop Bourdieu’s metaphor of 30 THE CULTURAL ECONOMY OF FANDOM describing culture as an economy in which people invest and accumulate capital. -

Expressions in Fan Culture

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Expressions in Fan Culture Cosplay, Fan Art, Fan Fiction Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Ragnhildur Björk Jóhannsdóttir Kt.: 210393-2189 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir Maí 2017 Expressions in Fan Culture Abstract This composition is a BA thesis for Japanese Language and Culture at the University of Iceland. In this essay, I will give the reader a little insight into the world of fan culture and will be focusing on how fans express themselves. Fans get inspired by books, movies and television programmes to create all kinds of fan work; whether it is fan fiction, fan art, doujinshi, cosplay, or any other creations. Furthermore, the thesis will explore fan culture as it presents itself in Japan and compare it to fan culture in Europe and the USA. I will discuss the effect these creations, although mainly fan fiction, has on authors of popular media and on social media and how the Internet has made it easier for fans all over the world to connect, as well as for fans and creators to connect. 2 Expressions in Fan Culture Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 2 Contents .................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 4 What is Fan Culture .................................................................................................. -

An Examination of Otaku Masculinity in Japan

!"#$%&'($)*&+',-(&.#(&/'(&0'"&(/#&(/"##1+23#,42',$%5!& $,$32,$(2',&'0&'($)*&3$47*%2,2(8&2,&9$:$,& & & $&(/#424& :;<=<>?<@&?A& (B<&0CDEF?G&AH&?B<&+<IC;?J<>?&AH&$=KC>&4?E@K<=& 7AFA;C@A&7AFF<L<& & & & 2>&:C;?KCF&0EFHKFFJ<>?&AH&?B<&"<MEK;<J<>?=&HA;&?B<&+<L;<<& NCDB<FA;&AH&$;?=& & NG&& N<>OCJK>&)K<PFCP& 3CG&QRST& & & & '>&JG&BA>A;5&25&N<>OCJK>&)K<PFCP5&BCU<&>A?&;<D<KU<@&C>G&E>CE?BA;KV<@& C==K=?C>D<&A>&?BK=&?B<=K=W&2&BCU<&HEFFG&EIB<F@&?B<&/','"&7'+#&AH&7AFA;C@A& 7AFF<L<W&& & & & & & & & XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX& & N#,9$32,&)2#)%$)& & & & & & & & Q& & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & ^& & ($N%#&'0&7',(#,(4& & & /A>A;&7A@<WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWQ& & "<C@<;`=&$II;AUCFWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWY& & (C\F<&AH&7A>?<>?=&WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW_& & (C\F<=WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWa& & 2>?;A@ED?KA>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWb& & 7BCI?<;&S]&/K=?A;KDCF&7A>?<c?WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWSQ& & 7BCI?<;&Q]&'?CPE&K>&?B<&:;<=<>?&+CGWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWQQ& & 7BCI?<;&Y]&3C=DEFK>K?G&K>&9CIC>]&'?CPE&C>@&4CFC;GJ<>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWYS& & 7A>DFE=KA>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW^R& -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

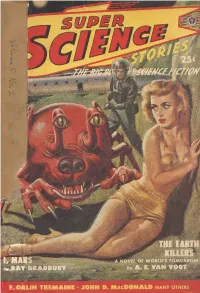

Super Science Stories V05n02 (1949 04) (Slpn)

’yf'Ti'-frj r " J * 7^ i'irT- 'ii M <»44 '' r<*r^£S JQHN D. Macdonald many others ) _ . WE WILL SEND ANY ITEM YOU CHOOSE rOR APPROVAL UNDER OUR MONEY BACK GUARANTEE Ne'^ MO*' Simply Indicate your selection on the coupon be- low and forward it with $ 1 and a brief note giv- ing your age, occupotion, and a few other facts about yourself. We will open an account for ycu and send your selection to you subject to your examination, tf completely satisfied, pay the Ex- pressman the required Down Payment and the balance In easy monthly payments. Otherwise, re- turn your selection and your $1 will be refunded. A30VC112 07,50 A408/C331 $125 3 Diamond Engagement 7 Dtomond Engagement^ Ring, matching ‘5 Diamond Ring, matching 8, Dior/tond Wedding Band. 14K yellow Wedding 5wd. 14K y<dlow or IBK white Gold. Send or I8K white Cold, fiend $1, poy 7.75 after ex- $1, pay .11.50 after ex- amination, 8.75 a month. aminatioii, 12.50 a month. ^ D404 $75 Man's Twin Ring with 2 Diamonds, pear-shaped sim- ulated Ruby. 14K yellow Gold. Send $1, pay 6.50 after examination, 7.50 a month* $i with coupon — pay balance op ""Tend [ DOWN PAYMENT AFTER EXAMINATION. I, ''All Prices thciude ''S T'" ^ ^ f<^erat fox ", 1. W. Sweet, 25 West 1 4th St. ( Dept. PI 7 New York 1 1, N, Y. Enclosed find $1 deposit. Solid me No. , , i., Price $ - After examination, I ogree to pay $ - - and required balance monthly thereafter until full price . -

You Zombies, Click and a Novel, 1632, Both of Which Are Available Online from Links in the Handout

Instructor's notes to F402 Time Travel in Science Fiction Session 1 – Introduction Welcome to F402, Time Travel in Science Fiction. The objective of this course is to help you to read, understand and enjoy stories in the genre. The course is in two parts; the first is Today's lecture and discussion on the genre while the second is class discussions of two stories of opposite types. click The reading assignment consists of a short story, All You Zombies, click and a novel, 1632, both of which are available online from links in the handout. click For the convenience of those who prefer dead trees, I have listed a number of anthologies1 containing All You Zombies. Reading Assignment for Sessions 2-3 click All You Zombies is one of two tour de force stories by Robert A. Heinlein that left their mark on the genre for decades. Please read All You Zombies prior to the next session click and 1632 click click Part One, chapters 1-14 prior to the third session. Esc Session 1 Keep in mind that science fiction is a branch of literature, so the normal criteria of, e.g., characterization, consistency, continuity, plot structure, style, apply; I welcome comments, especially from those who have expertise in those areas. In addition, while a science fiction author must rely on the willing suspension of disbelief, he should do so sparingly. There is a lapse of continuity in 1632 between chapters 8 and 9; see whether you can spot it. I will suggest specific discussion points to start each discussion, but please bring up any other issues that you believe to be important or interesting. -

Book Review: Only at Comic-Con: Hollywood, Fans, and the Limits of Exclusivity Hanna, Erin NEWARK: RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2020

Media Industries 7.2 (2020) Book Review: Only at Comic-Con: Hollywood, Fans, and the Limits of Exclusivity Hanna, Erin NEWARK: RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2020. Tanya D. Zuk1 GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY tzuk1 [AT] gsu.edu Comic-Con International: San Diego, known colloquially as Comic-Con, is one of the largest and most influential fan conventions in the world. Comic-Con as an event and as a brand has impacted fandom, popular culture, and, more importantly, for Erin Hanna, the media industries in Hollywood. Since its inception, Comic-Con has been intertwined with the media industries: comic creators and industry professionals attended the very first conven- tion. Comic-Con has, however, expanded beyond comic books to include all popular media and has opened its doors to industry creatives, synergistic promotion, and audience testing, making Comic-Con a useful event for Hollywood’s buzz machine.2 Comic-Con, as both an exclusive event and a franchise, has made fan conventions widely popular (and lucrative) with both audiences and global pop- ular culture industries. In this book, Hanna explores how Hollywood studios and related industries foster the appeal of exclusivity as a means of promotion that exploits fan labor. Media Industries 7.2 (2020) In Only at Comic-Con, Erin Hanna uses a framework of exclusivity to dismantle the power structures embedded in fan conventions generally and Comic-Con specifically. According to Hanna, “exclusivity is not defined by presences at all, but by the power to produce absences.”3 Hanna outlines the power dynamics between media industry representatives and conven- tion organizers (and fans), between fans and convention staff, and between fans themselves. -

Nebula Conference Release

For Immediate Release May 26, 2020 For More Information Kevin Lampe (312) 617-7280 [email protected] Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America’s 2020 Nebula Conference THREE DAYS OF ONLINE VIDEO PANELS WITH REAL-TIME INTERACTION MAY 29 – 31 The SFWA Nebula Conference -- the premier professional development conference for science fiction and fantasy writers -- is transforming into an entirely virtual conference this year, presented live and in interactive form from May 29th-31st. The innovative program will convey the essence of the in-person Nebula Conference, albeit in an all-online format due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “The vision is for attendees to feel elevated through the content, enjoy a sense of community with their peers, and have an opportunity for celebration,” said Mary Robbinette Kowal, SFWA President. This year’s transformed Nebula Conference will include two live tracks of live-streamed panels and a third self- guided track of pre-recorded presentations which attendees can view at their leisure. The Nebula Conference will also include, solo presentations, conference mentorships, workshops, writing forums, chats, and virtual room parties (including a dance party hosted by John Scalzi). A portion of funds raised by the conference will go to SFWA’s “Where The Need Is Greatest” fund, to assist SFWA members financially affected by COVID-19. And, of course, the Nebula Awards ceremony will be streamed live to conference attendees and the public alike at 8 pm Eastern on May 30th. Please visit https://events.sfwa.org/events/ for the latest schedule and event details. About the Nebulas The Nebula Awards® are voted on, and presented by, full members of Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Inc.