New Neighborhood Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

Housing & Development Bank Group

INDEX Notes to the Separate Housing & Development Bank Financial Statements Vision & Mission 4 Notes to the Separate Financial Statements 56 Shareholding Structure 6 Financial Highlights 8 Chairman’s Forward 10 Head Office and Branches Head Office and Branches 117 Management of the Bank Board of Directors 18 Housing & Development Heads of Divisions, Regionals and Zones 22 Bank Group Bank’s Committees 26 Auditors’ Report 138 Board Statement 30 Consolidated Balance Sheet 140 Consolidated Income Statement 142 Consolidated Cash Flows Statement 144 Separate Financial Reports Consolidated Changes in Shareholders’ Statement 146 Independent Auditors’ Report 42 Separate Balance Sheet 44 Separate Income Statement 46 Separate Cash Flows Statement 48 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements Separate Changes in Shareholders’ Equity Statement 50 Profit Dividends Statement 52 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 150 2 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 3 Vision & Mission HDBank Vision HDBank Mission To be within the top ten ranked commercial banks in the Striving to excel in providing both banking and real banking sector, while working on sustaining the current estate services as well as mortgage while continuously high operating efficiency. upgrading our human capital to reach a distinguished level of services for our clients to serve their needs and aspirations of the shareholders. 4 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 5 Shareholding Structure as at 31/12/2018 Share per unit Total share Government Institutions Public Sector Institutions -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Nationality Egyptian 17th November, 1956 - Giza, Egypt Birth Date & Place Languages Arabic (native), English (Fluent), French (Fluent) Dr. Sahar Attia - Professor of Architecture, Urban Design and Planning, Department of Architecture at the Faculty of Engineering - Cairo University. (CUFE) - MD of Associated Consultants, Head of Planning Professional Title /urban design and Community Development sector. - Urban Development Consultant ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL RECORD Academic Degrees 1988 Ph.D., Urban Planning- Urban Institute of Paris – University of Paris 12 – France . (with distinction). Thesis: “Impacts of Rapid Mass Transit System On The Dynamics Of Cairo Agglomeration” 1986 Advanced Studies Diploma in Urban Planning - Urban Institute of Paris, University of Paris 12 - France Specialization: “The Dynamics Of Cairo CBD, Transportation's Issues”. 1984 Master of Science in Architecture - Faculty of Engineering, Cairo, University, Giza, Egypt. (CU) Thesis: “ Factors Affecting The Formation Of The Arabic Islamic Cities, An Analytical Study” 1979 B.Sc. Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, C.U Key Qualification - 35 Years Of Experience practicing urban planning , community development, Architecture, and Urban Design & in the academic and professional Field. After the Architectural bachelor, I carried out studies in urban Planning , and urban design to achieve a comprehensive education, and practice . - Areas Of Specialization Include: Urban Regeneration, Upgrading the deteriorated and informal areas, Strategic -

PNAAQ378.Pdf

Trn'ot ma..in Ais An M thd e II ar Fial Replot :VOIu rmrdte(pw '(rf Ih Iu VOLUME III PART I Basic Oata Elaboration VOLUME III Transport Planning Aids and Methods for Cairo Urban Area Introduction : the Massachusetts Institute of Since 1977, Cairo University (CU) and in a multi-faceted technology Technology (MIT) have worked cooperatively needs of Egypt. One component of a"aptation program addressing research system in Cairo; within this program has been the urban transportation topics was examined. Before this component, a wide range of research topics, it is useful to first detailing methods and findings of these Research Project. This review the goals of the Urban Transportation professionals in Cairo cooperative effort between MIT and transportation is designed to: planning insti -Improve and broaden capabilities of academic and in Egypt. tutions concerned with transportation data base that can be - Establish a .comprehensive and reliable can be periodically used in transportation studies and that agencies. tested and updated by appropriate governmental planning models and methods - Adapt and calibrate those transport most suitable for Cairo. and - Formulate and test the sensitivity of transportation behavior traffic performance to alternative transportation investment, management, and government policies. agenda, covering These broad goals lead to a rather varied research making, planning, and many aspects of transportation operations, decision made in developing programming. Volume III describes the achievements research agenda. transport planning aids and methods as part of this of which is des There are five major sections to this volume, each cribed briefly below : Basic Data Elaboration, Volume III, Part (1) transport in Cairo and Two traffic surveys-a 1977 survey of private the bdsis for much of the a 1978 survey of public trausport use-form S ii research in this project. -

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2 Metlife Clinic - Cairo Medical Center 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Metlife Clinic 02 24509800 02 22580672 Hospital Heliopolis Emergency- 39 Cleopatra St. Salah El Din Sq., Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Cleopatra Hospital Gold Outpatient- 19668 Heliopolis Inpatient ( Except Emergency- 21 El Andalus St., Behind Cairo Heliopolis Hospital International Eye Hospital Gold 19650 Outpatient-Inpatient Mereland , Roxy, Heliopolis Emergency- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital San Peter Hospital Green 3 A. Rahman El Rafie St., Hegaz St. 02 21804039 02 21804483-84 Outpatient-Inpatient Emergency- 16 El Nasr st., 4th., floor, El Nozha Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Ein El Hayat Hospital Green 02 26214024 02 26214025 Outpatient-Inpatient El Gedida Cairo Medical Center - Cairo Heart Emergency- 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Silver 02 24509800 02 22580672 Center Outpatient-Inpatient Heliopolis Inpatient Only for 15 Khaled Ibn El Walid St. Off 02 22670702 (10 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital American Hospital Silver Gynecology and Abdel Hamid Badawy St., Lines) Obstetrics Sheraton Bldgs., Heliopolis 9 El-Safa St., Behind EL Seddik Emergency - Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Nozha International Hospital Silver Mosque, Behind Sheraton 02 22660555 02 22664248 Inpatient Only Heliopolis, Heliopolis 91 Mohamed Farid St. El Hegaz Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Al Dorrah Heart Care Hospital Orange Outpatient-Inpatient 02 22411110 Sq., Heliopolis 19 Tag El Din El Sobky st., from El 02 2275557-02 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Nozha st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 22738232 2 Samir Mokhtar st., from Nabil El 02 22681360- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Wakad st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 01225320736 Dr. -

QNB ALAHLI Enjoys a Blend of Local Experience, Based on Years of Confidence in the Egyptian Market, and the International Expertise of QNB Group

QNB ALAHLI enjoys a blend of local experience, based on years of confidence in the Egyptian market, and the international expertise of QNB Group. 2 — QNB ALAHLI Annual Report 20192018 Overview As part of QNB Group, we at QNB ALAHLI, Strategic Report seek to contribute to the group’s aspiration to become a leading bank in MEASEA by 2020 and a global icon in 2030. Read more about our Strategy on page 12 Performance Operational Contents Corporate Social Responsibility Overview 4 QNB ALAHLI Chairman and Managing Director’s Statement Assets Net profit 6 Board of Directors EGP 273,014 m EGP 8,522 m Strategic Report 10 QNB ALAHLI at a glance Risk Management Net Profit YOY Earnings Per Governance and 12 QNB ALAHLI’s Strategy growth share Corporate 16 Delivering sustainable results 18 Creating and delivering value 18% EGP 7.63 Operational Performance Read more in our Financial statements section on page 44 22 Wholesale and Commercial banking Separate Financial 23 Retail banking Statements 25 Small and Medium Enterprises Corporate Social Responsibility 28 QNB ALAHLI’s corporate social responsibility Corporate Governance and Risk Consolidated Statements Management Financial 32 Corporate Governance 38 Internal Audit 40 Compliance 42 Risk Management Financial Statements Branches Network 44 Separate Financial Statements 110 Consolidated Financial Statements 184 QNB ALAHLI’s Branches Network QNB ALAHLI Annual Report 2019 — 3 QNB ALAHLI During 2020, we will continue to provide the best Chairman & Managing and most innovative digital banking products Director’s Statement and services to meet our customers’ needs while ensuring speed of service and full compliance with safety standards. -

Public Transport Survey 1978

CAIRO URBAN TRANSPORTATION PROJECT PUBLIC TRANSPORT SURVEY 1978 IJ 'A. SPONSORED BY U.S -A.I.D. UNDER THE AUSPICES OF H.EENG. A.F. EL-DAGHESTANY PREPARED BY ROE DR. M.EL-HAWARY ENG.A.H.EL-SALMAWY DR. F.ABDEL- BARY DRTAREK EL-REEDY DR.M.OWAIS ENG.M.HISHAM EL-SHERIF JUNE 1979 THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SURVEY REPORT List of Contents A. Preparation and Execution of the Survey B. Data Collection C. The Coding Syster D. System Design of the Computer Work E. Data Processing Implementation F. Appendices Appendix I Different Forms Used for Data Collection and Porms Used in Manual Data Processing. Appendix II Distribution of Survey Manpower, and the Different Modes Surveyed. Appendix III Instruction Sheets for the Interviewers Appendix IV Different Zones and aps of the Srudy Area. Appendix V Sample of Output Results. PREFACE The first phase of the Urban Transportation Project outlined in the project proposal of March 3, 1977 waR completed. Traffic volumes and vehicular travel behavior in the greater Cairo metropolitan area have been monitored, and standard survey procedures and documents have been developed. Work is in progress to apply a traffic assignment model which will predict traffic flows and speeds given alternative forms of the Cairo street network. The transit portion of the travel behavior surveys, forming the second phase of the project, was excluded from the first year's program since resources were limited. Hence, the principal purpose of this year's research is to investi gate mass transit. There are additional reasons for doing this: - Inspite of the fact that vehicle traffic on the street net work is normally the basis for expansion of system capacity, well over 60% of the total daily mechanised trips are made by public transit in comparison to only 8% by private modes. -

Annaulreport MISR BANK 2004-2005.Pdf

Mr. Mohamed Kamal El Din Barakat Chairman During the fiscal year 2004/2005, the Egyptian government undertook significant structural reforms to the financial and monetary policies that led to an increase in the GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate to 5.1% compared to 4.2% in the previous year as well as a reduction of the inflation rate to 4.7%. Furthermore, the foreign exchange markets witnessed stability and the monetary reserves of foreign currencies increased to more than $20 Billion. This improvement was reflected upon all market sectors including banking. Consequently, it impacted Banque Misr's financial achievements for this year where total assets had grown by 17.3% to reach L.E 106.8 billion. As for the deposits, they grew by 16.3% to reach L.E 93.2 Billion and the shareholders' equity increased by 2.6% to reach L.E 3.5 Billion. Concerning loans, the total loans portfolio grew by 3.8% to reach L.E 37.8 billion. Furthermore, the bank continued its support for small and micro finance projects by offering credit facilities engaging higher employment rates for economy support. The financial investments increased by 26% to reach L.E. 39.1 Billion. In this context, the Bank's newly introduced investment fund with daily current revenue (day by day account) was highly accepted by the customers. This was reflected by the increase of its net value from L.E. 200 Million on its issuance date during August 2004 to reach more than L.E. 2 Billion by the end of July 2005, the total profits before provisions and taxes increased by 74.3% to reach L.E. -

Pizza Market Egypt Overvieww

Pizza Market Overview Egypt Pillars consultancy www.PILLARS-EG.COM [email protected] Table of contents • Pizza - Italian Restaurants Classification/ Products Offered • Pizza – Italian Outlets Egypt Nation-Wide (1/3) : • Review to Pizza Local Market – Pizza Hut – Domino’s Pizza – PAPA John’s – Little Caesars – Pizza King – Peppes Pizza – Cortigiano – Roma Pizza 2 Go – Pizza Plus • Other Pizza Outlets Online Ordering / Others 2 Pizza & Italian Restaurants Table of Contents : Pizza Hut Sbarro Papa Johns Little Caesars Pizza Roma Domino’s Pizza Pizza King Peppes Pizza Cortigiano La Casetta Majesty 3 Pizza - Italian Restaurants Classification/ Products Offered Local Local Italian Restaurant Pizza Chains Local Offer/ International Local Chains * Pizza/ Oriental Pizza + Type Pizza Chains Pizza Chains + Individual Restaurants Fast Food (Feteer) Avg. Class Class A/B A+B A+B B B+C Example Pizza Hut / Little Cesares/sbarro Pizza Y Y Y Y Italian Food Y Y Y Y Oriental Pizza - - - - Fast Food - - Y Y Others Y Y Pizza Hut Thomas Lacasetta Pizza King Majesty Papa John’s Tabasco Cortigiano/ Pizza Plus Dawwar/ Example Sbarro Pizza Pomodoro/Condetti/ Cook Door Pepes Pizza Little Caesars Not Much preferred as Much Preferred for Class outing for class A as A as perceived as outlets Comments preference towards Local of the choice for Pizza Italian Chains High Average Check / higher than Average 4 Pizza – Italian Outlets Egypt Nation-Wide (1/3) : Int’l Local Other “On-line” Chains Chains* Chains & Outlets La Rosa 19 Road, Degla, Maadi shahiya.com La Casetta -

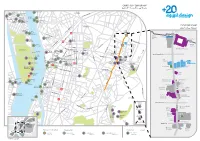

Cairo - City Center Map

CAIRO - CITY CENTER MAP Golden Fairmont Hotel Flamenco Don Quichotte SHUBRA Hotel Restaurant 6th of Oct Bridge Sangria Conrad Hotel Sawy Abul seed Restaurant Cultural wheel Restaurant Faculty of Resident World Trade Fine Arts Hotel Center EVENT AREA MAP RAMSIS Marriot MAIN Hotel Nile th of Oct Bridge Bab al-Futuh Maxim 6 ENTRANCE Restaurant s 26 th of July st Fatimid Ramses Northern Info Point Islamic Hilton Arabic Walls Bab al-Nasr Ceramics Ramsis st Music Museum Institute El Banhawi st Le Pasha TAHRIR Wikalat Restaurants th of Oct Bridge Qaytbay 6 Abdel Adly st El Geish st Opera Al-Hakim Mosque ZAMALEK Koshary Khalek Tharwat st Square Egyptian Abu Tarek Kasr El Nil 6th of Oct Bridge Museum Restaurant Square Kekhia Port Said st Mosque Khan El Khalili El Muiz st Amir El Guyushi St. Market Nile City After Eight El Qalaa st Restaurants Restaurant El Azhar st Talaat HarbKasr st El Nil st Cairo Tower Arabesk Talaat Harb Restaurant Square DOWN TOWN El Hussein Sabil Mosque Al Silihdar Semiramis Café Riche to FURNEX El Ghouri to the airport Al Azhar Opera House Nil El Corniche InterContinental Koshary Complex Studio Misr Mohamed Farid st Mosque El Tahrir Restaurant Suhaymi Tahrir Restaurant Museum of Modern Hotel Le Riad Shepheard Square Egyptian Art Hotel Mohamed Mahmud st Ahmed Maher St. Azhar Park Salah Salem Aqmar EL Horreya Mosque Garden Rare Books Library Pyramisa Hotel El Tahrir st El Kababgi Hasan al Sha’rawi Sabil-Katkhuda Restaurant Taboula Kathuda Mosque Dr. Ragab’s Restaurant Amir Sotel Papyrus El Muiz st Bashtak El Gezirah Corniche El Nil Institute El Kasr El Aini st Hamam Inal Palace Cairo Felucca El Monsour st Sheraton Ride Spot GARDEN CITY Qalawun Bait El Shaer Uthman Complex Textile Kathuda Museum House Ezz El Arab st Mohamed M. -

Businessmen and Authoritarianism in Egypt

Businessmen and Authoritarianism in Egypt Safinaz El Tarouty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of East Anglia, School of Political, Social and International Studies. Norwich, May 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract The main concern of this thesis is to examine how the Mubarak authoritarian regime survived for three decades, especially after the introduction of economic liberalization. I argue that the Mubarak regime created a new constituency of businessmen who benefited from economic reform and in return provided support to the regime. Based on interviews with Egyptian businessmen and political activists, this thesis examines the different institutional mechanisms used by the regime to co-opt businessmen and based on predation of public and private resources. Extending the literature on clientelism, I create a typology of regime-businessmen relations in terms of authoritarian clientelism, semi-clientelism, patron-broker client relationships, and mutual dependency. The thesis further examines how the regime dealt with an opposition that refused to enter into its clientelisitic chain. I demonstrate how the regime weakened this opposition by creating among them a divided political environment on different levels (i.e., among the legal and illegal opposition, inside the legal opposition, and among the illegal opposition). This thesis demonstrates that there are businessmen who are supportive of authoritarianism; however, they may also oppose authoritarian regimes, not for their own business interests but rather for their own political/ideological stance. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance,