Tainted Ideals: the Rise and Fall of the Tupamaros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GURU'guay GUIDE to URUGUAY Beaches, Ranches

The Guru’Guay Guide to Beaches, Uruguay: Ranches and Wine Country Uruguay is still an off-the-radar destination in South America. Lucky you Praise for The Guru'Guay Guides The GURU'GUAY GUIDE TO URUGUAY Beaches, ranches Karen A Higgs and wine country Karen A Higgs Copyright © 2017 by Karen A Higgs ISBN-13: 978-1978250321 The All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever Guru'Guay Guide to without the express written permission of the publisher Uruguay except for the use of brief quotations. Guru'Guay Productions Beaches, Ranches Montevideo, Uruguay & Wine Country Cover illustrations: Matias Bervejillo FEEL THE LOVE K aren A Higgs The Guru’Guay website and guides are an independent initiative Thanks for buying this book and sharing the love 20 18 Got a question? Write to [email protected] www.guruguay.com Copyright © 2017 by Karen A Higgs ISBN-13: 978-1978250321 The All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever Guru'Guay Guide to without the express written permission of the publisher Uruguay except for the use of brief quotations. Guru'Guay Productions Beaches, Ranches Montevideo, Uruguay & Wine Country Cover illustrations: Matias Bervejillo FEEL THE LOVE K aren A Higgs The Guru’Guay website and guides are an independent initiative Thanks for buying this book and sharing the love 20 18 Got a question? Write to [email protected] www.guruguay.com To Sally Higgs, who has enjoyed beaches in the Caribbean, Goa, Thailand and on the River Plate I started Guru'Guay because travellers complained it was virtually impossible to find a good guidebook on Uruguay. -

Los Frentes Del Anticomunismo. Las Derechas En

Los frentes del anticomunismo Las derechas en el Uruguay de los tempranos sesenta Magdalena Broquetas El fin de un modelo y las primeras repercusiones de la crisis Hacia mediados de los años cincuenta del siglo XX comenzó a revertirse la relativa prosperidad económica que Uruguay venía atravesando desde el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A partir de 1955 se hicieron evidentes las fracturas del modelo proteccionista y dirigista, ensayado por los gobiernos que se sucedieron desde mediados de la década de 1940. Los efectos de la crisis económica y del estancamiento productivo repercutieron en una sociedad que, en la última década, había alcanzado una mejora en las condiciones de vida y en el poder adquisitivo de parte de los sectores asalariados y las capas medias y había asistido a la consolidación de un nueva clase trabajadora con gran capacidad de movilización y poder de presión. El descontento social generalizado tuvo su expresión electoral en las elecciones nacionales de noviembre de 1958, en las que el sector herrerista del Partido Nacional, aliado a la Liga Federal de Acción Ruralista, obtuvo, por primera vez en el siglo XX, la mayoría de los sufragios. Con estos resultados se inauguraba el período de los “colegiados blancos” (1959-1966) en el que se produjeron cambios significativos en la conducción económica y en la concepción de las funciones del Estado. La apuesta a la liberalización de la economía inauguró una década que, en su primera mitad, se caracterizó por la profundización de la crisis económica, una intensa movilización social y la reconfiguración de alianzas en el mapa político partidario. -

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗ Jennifer Alix-Garcia Laura Schechter Felipe Valencia Caicedo Oregon State University UW Madison University of British Columbia S. Jessica Zhu Precision Agriculture for Development April 5, 2021 Abstract Skewed sex ratios often result from episodes of conflict, disease, and migration. Their persistent impacts over a century later, and especially in less-developed regions, remain less understood. The War of the Triple Alliance (1864{1870) in South America killed up to 70% of the Paraguayan male population. According to Paraguayan national lore, the skewed sex ratios resulting from the conflict are the cause of present-day low marriage rates and high rates of out-of-wedlock births. We collate historical and modern data to test this conventional wisdom in the short, medium, and long run. We examine both cross-border and within-country variation in child-rearing, education, labor force participation, and gender norms in Paraguay over a 150 year period. We find that more skewed post-war sex ratios are associated with higher out-of-wedlock births, more female-headed households, better female educational outcomes, higher female labor force participation, and more gender-equal gender norms. The impacts of the war persist into the present, and are seemingly unaffected by variation in economic openness or ties to indigenous culture. Keywords: Conflict, Gender, Illegitimacy, Female Labor Force Participation, Education, History, Persistence, Paraguay, Latin America JEL Classification: D74, I25, J16, J21, N16 ∗First draft May 20, 2020. We gratefully acknowledge UW Madison's Graduate School Research Committee for financial support. We thank Daniel Keniston for early conversations about this project. -

Uruguay: an Overview

May 8, 2018 Uruguay: An Overview Uruguay, a small nation of 3.4 million people, is located on Figure 1.Uruguay at a Glance the Atlantic coast of South America between Brazil and Argentina. The country stands out in Latin America for its strong democratic institutions; high per capita income; and low levels of corruption, poverty, and inequality. As a result of its domestic success and commitment to international engagement, Uruguay plays a more influential role in global affairs than its size might suggest. Successive U.S. administrations have sought to work with Uruguay to address political and security challenges in the Western Hemisphere and around the world. Political and Economic Situation Uruguay has a long democratic tradition but experienced 12 years of authoritarian rule following a 1973 coup. During the dictatorship, tens of thousands of Uruguayans were Sources: CRS Graphics, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de forced into political exile; 3,000-4,000 were imprisoned; Uruguay, Pew Research Center, and the International Monetary Fund. and several hundred were killed or “disappeared.” The country restored civilian democratic governance in 1985, The Broad Front also has enacted several far-reaching and analysts now consider Uruguay to be among the social policy reforms, some of which have been strongest democracies in the world. controversial domestically. The coalition has positioned Uruguay on the leading edge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and President Tabaré Vázquez of the center-left Broad Front transgender (LGBT) rights in Latin America by allowing was inaugurated to a five-year term in March 2015. This is LGBT individuals to serve openly in the military, legalizing his second term in office—he previously served as adoption by same-sex couples, allowing individuals to president from 2005 to 2010—and the third consecutive change official documents to reflect their gender identities, term in which the Broad Front holds the presidency and and legalizing same-sex marriage. -

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

The Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations

Volume 41, Number 3, January 2011 assp rt PThe Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations Inside... Nixon, Allende, and the White House Tapes Roundtable on Dennis Merrill’s Negotiating Paradise Teaching Diplomatic History to Diplomats ...and much more! Passport The Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations Editorial Office: Mershon Center for International Security Studies 1501 Neil Avenue Columbus OH 43201 [email protected] 614-292-1681 (phone) 614-292-2407 (fax) Executive Director Peter L. Hahn, The Ohio State University Editor Mitchell Lerner, The Ohio State University-Newark Production Editor Julie Rojewski, Michigan State University Editorial Assistant David Hadley, The Ohio State University Cover Photo President Nixon walking with Kissinger on the south lawn of the White House, 08/10/1971. ARC Identifier 194731/ Local Identifier NLRN-WHPO-6990-18A. Item from Collection RN-WHPO: White House Photo Office Collection (Nixon Administration), 01/20/1969-08/09/1974. Editorial Advisory Board and Terms of Appointment Elizabeth Kelly Gray, Towson University (2009-2011) Robert Brigham, Vassar College (2010-2012) George White, Jr., York College/CUNY (2011-2013) Passport is published three times per year (April, September, January), by the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, and is distributed to all members of the Society. Submissions should be sent to the attention of the editor, and are acceptable in all formats, although electronic copy by email to [email protected] is preferred. Submis- sions should follow the guidelines articulated in the Chicago Manual of Style. Manuscripts accepted for publication will be edited to conform to Passport style, space limitations, and other requirements. -

INTELLECTUALS and POLITICS in the URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This Thesis Is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements

INTELLECTUALS AND POLITICS IN THE URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies at the University of New South Wales 1998 And when words are felt to be deceptive, only violence remains. We are on its threshold. We belong, then, to a generation which experiences Uruguay itself as a problem, which does not accept what has already been done and which, alienated from the usual saving rituals, has been compelled to radically ask itself: What the hell is all this? Alberto Methol Ferré [1958] ‘There’s nothing like Uruguay’ was one politician and journalist’s favourite catchphrase. It started out as the pride and joy of a vision of the nation and ended up as the advertising jingle for a brand of cooking oil. Sic transit gloria mundi. Carlos Martínez Moreno [1971] In this exercise of critical analysis with no available space to create a distance between living and thinking, between the duties of civic involvement and the will towards lucidity and objectivity, the dangers of confusing reality and desire, forecast and hope, are enormous. How can one deny it? However, there are also facts. Carlos Real de Azúa [1971] i Acknowledgments ii Note on references in footnotes and bibliography iii Preface iv Introduction: Intellectuals, Politics and an Unanswered Question about Uruguay 1 PART ONE - NATION AND DIALOGUE: WRITERS, ESSAYS AND THE READING PUBLIC 22 Chapter One: The Writer, the Book and the Nation in Uruguay, 1960-1973 -

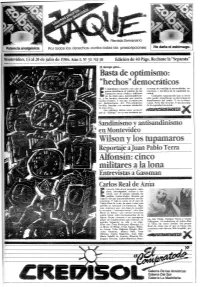

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Vi Brazil As a Latin American Political Unit

VI BRAZIL AS A LATIN AMERICAN POLITICAL UNIT I. PHASES OF BRAZILIAN HISTORY is almost a truism to say that interest in the history of a I' country is in proportion to the international importance of it as a nation. The dramatic circumstances that might have shaped that history are of no avail to make it worth knowing; the actual or past standing of the country and its people is thus the only practical motive. According to such an interpretation of historical interest, I may say that the international importance of Brazil seems to be growing fast. Since the Great War, many books on South America have been published in the United States, and abundant references to Brazil may be found in all of them. Should I have to mention any of the recent books, I would certainly not forget Herman James's Brazil after a Century,' Jones's South Amer- ica,' for the anthropogeographic point of view, Mary Wil- liams's People and Politics oj Latin Arneri~a,~the books of Roy Nash, J. F. Normano, J. F. Rippy, Max Winkler, and others. Considering Brazil as a South American political entity, it is especially the historical point of view that I purpose to interpret. Therefore it may be convenient to have a pre- liminary general view of the story of independent Brazil, 'See reference, Lecture V, p. 296. IC. F. Jones, South America (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1930). Wary W. Williams, The People and Politics of Latin America (Boston: Ginn & CO., 1930). 312 Brazil as a Political Unit 313 emphasizing the characteristic features of the different pe- riods. -

URUGUAY: the Quest for a Just Society

2 URUGUAY: ThE QUEST fOR A JUST SOCiETY Uruguay’s new president survived torture, trauma and imprisonment at the hands of the former military regime. Today he is leading one of Latin America’s most radical and progressive coalitions, Frente Amplio (Broad Front). In the last five years, Frente Amplio has rescued the country from decades of economic stagnation and wants to return Uruguay to what it once was: A free, prosperous and equal society, OLGA YOLDI writes. REFUGEE TRANSITIONS ISSUE 24 3 An atmosphere of optimism filled the streets of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Montevideo as Jose Mujica assumed the presidency of Caribbean, Uruguay’s economy is forecasted to expand Uruguay last March. President Mujica, a former Tupamaro this year. guerrilla, stood in front of the crowds, as he took the Vazquez enjoyed a 70 per cent approval rate at the end oath administered by his wife – also a former guerrilla of his term. Political analysts say President Mujica’s victory leader – while wearing a suit but not tie, an accessory he is the result of Vazquez’s popularity and the economic says he will shun while in office, in keeping with his anti- growth during his time in office. According to Arturo politician image. Porzecanski, an economist at the American University, The 74-year-old charismatic new president defeated “Mujica only had to promise a sense of continuity [for the National Party’s Luis Alberto Lacalle with 53.2 per the country] and to not rock the boat.” cent of the vote. His victory was the second consecutive He reassured investors by delegating economic policy mandate for the Frente Amplio catch-all coalition, which to Daniel Astori, a former economics minister under the extends from radicals and socialists to Christian democrats Vazquez administration, who has built a reputation for and independents disenchanted with Uruguay’s two pragmatism, reliability and moderation. -

The United States and the Uruguayan Cold War, 1963-1976

ABSTRACT SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 In the early 1960s, Uruguay was a beacon of democracy in the Americas. Ten years later, repression and torture were everyday occurrences and by 1973, a military dictatorship had taken power. The unexpected descent into dictatorship is the subject of this thesis. By analyzing US government documents, many of which have been recently declassified, I examine the role of the US government in funding, training, and supporting the Uruguayan repressive apparatus during these trying years. Matthew Ford May 2015 SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 by Matthew Ford A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Matthew Ford Thesis Author Maria Lopes (Chair) History William Skuban History Lori Clune History For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in part or in its entirety must be obtained from me. -

Uruguay Year 2020

Uruguay Year 2020 1 SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED Table of Contents Doing Business in Uruguay ____________________________________________ 4 Market Overview ______________________________________________________________ 4 Market Challenges ____________________________________________________________ 5 Market Opportunities __________________________________________________________ 5 Market Entry Strategy _________________________________________________________ 5 Leading Sectors for U.S. Exports and Investment __________________________ 7 IT – Computer Hardware and Telecommunication Equipment ________________________ 7 Renewable Energy ____________________________________________________________ 8 Agricultural Equipment _______________________________________________________ 10 Pharmaceutical and Life Science _______________________________________________ 12 Infrastructure Projects________________________________________________________ 14 Security Equipment __________________________________________________________ 15 Customs, Regulations and Standards ___________________________________ 17 Trade Barriers _______________________________________________________________ 17 Import Tariffs _______________________________________________________________ 17 Import Requirements and Documentation _______________________________________ 17 Labeling and Marking Requirements ____________________________________________ 17 U.S. Export Controls _________________________________________________________ 18 Temporary Entry ____________________________________________________________