Vi Brazil As a Latin American Political Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecos Del Constitucionalismo Gaditano En La Banda Oriental Del Uruguay 11

Ecos del Constitucionalismo gaditano en la Banda Oriental del Uruguay 11 ECOS DEL CONSTITUCIONALISMO GADITANO EN LA BANDA ORIENTAL DEL URUGUAY AN A FREG A NOV A LES UNIVERSID A D DE L A REPÚBLIC A (UR U G ua Y ) RESUMEN El artículo explora las influencias de los debates y el texto constitucional aprobado en Cádiz en 1812 en los territorios de la Banda Oriental del Uruguay, durante dos dé- cadas que incluyen la resistencia de los “leales españoles” en Montevideo, el proyecto confederal de José Artigas, la incorporación a las monarquías constitucionales de Por- tugal y Brasil y la formación de un Estado independiente. Plantea cómo las discusiones doctrinarias sobre monarquía constitucional o república representativa, soberanía de la nación o soberanía de los pueblos, y centralismo o federalismo reflejaban antiguos con- flictos jurisdiccionales y diferentes posturas frente a la convulsión del orden social. PALABRAS CLAVE: Montevideo, Provincia Oriental, Provincia Cisplatina, Sobe- ranía, Constitución. ABSTRACT This article explores the influences of the debates and constitutional text approved in Cadiz in 1812 on Banda Oriental del Uruguay territories, during two decades that include the resistance of the “loyal Spaniards” in Montevideo, the confederate project of José Artigas, the incorporation to the constitutional monarchies of Portugal and Brazil and the creation of an independent State. Moreover, it poses how the doctrinaire TROCADERO (24) 2012 pp. 11-25 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25267/Trocadero.2012.i24.01 12 Ana Frega Novales discussions about constitutional monarchy or representative republic, sovereignty of the nation or sovereignty of the peoples, and centralism or federalism, reflected long- standing jurisdictional conflicts and different stances regarding the upheaval of the social order. -

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗ Jennifer Alix-Garcia Laura Schechter Felipe Valencia Caicedo Oregon State University UW Madison University of British Columbia S. Jessica Zhu Precision Agriculture for Development April 5, 2021 Abstract Skewed sex ratios often result from episodes of conflict, disease, and migration. Their persistent impacts over a century later, and especially in less-developed regions, remain less understood. The War of the Triple Alliance (1864{1870) in South America killed up to 70% of the Paraguayan male population. According to Paraguayan national lore, the skewed sex ratios resulting from the conflict are the cause of present-day low marriage rates and high rates of out-of-wedlock births. We collate historical and modern data to test this conventional wisdom in the short, medium, and long run. We examine both cross-border and within-country variation in child-rearing, education, labor force participation, and gender norms in Paraguay over a 150 year period. We find that more skewed post-war sex ratios are associated with higher out-of-wedlock births, more female-headed households, better female educational outcomes, higher female labor force participation, and more gender-equal gender norms. The impacts of the war persist into the present, and are seemingly unaffected by variation in economic openness or ties to indigenous culture. Keywords: Conflict, Gender, Illegitimacy, Female Labor Force Participation, Education, History, Persistence, Paraguay, Latin America JEL Classification: D74, I25, J16, J21, N16 ∗First draft May 20, 2020. We gratefully acknowledge UW Madison's Graduate School Research Committee for financial support. We thank Daniel Keniston for early conversations about this project. -

Uoyage of the Frigate Qongress, 1823

Uoyage of the Frigate Qongress, 1823 dawn on June 8, 1823, the United States Frigate Congress lay in readiness to quit her Delaware moorings off Wilmington A- and sail down the river. A steamboat edged alongside to permit a number of passengers to board her—ministers to two foreign countries and their suites. Then, at 5 A.M., the ship unmoored, top- gallant and royal yards were crossed, the boats were hoisted in and soon she was under way favored by a breeze from the north. Nor- mally her commander would have felt legitimate pride at this mo- ment as his beautiful ship, royals and studding sails set, stood for the open seas.1 But Captain James Biddle could take little pride in his vessel on this voyage. His sense of propriety and of the traditions of the service was wounded. The son of a former sea captain and a nephew of Captain Nicholas Biddle of Revolutionary fame, he was an officer of meticulous custom and taste.2 Joining the Navy in 1800 as a mid- shipman, his career had been an interesting and distinguished one: for nineteen months he had been a prisoner in Tripoli following the capture of the 'Philadelphia; during the War of 1812 he had led the Wasp's boarding party which took the Frolic, and had later, when commanding the Hornet> won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his capture of the Tenguin. Several years after the war he was sent to the Columbia River to take possession of Oregon Territory. Dur- ing his subsequent career he was to sign a commercial treaty with Turkey and the first treaty between the United States and China; to serve as governor of the Naval Asylum at Philadelphia, as com- modore of the West India station and of the East Indian Squadron, and as commander of naval forces on the Pacific Coast during the Mexican War. -

From the Uruguayan Case to the Happiness Economy

Dipartimento di Impresa e Management Cattedra: International Macroeconomics and Industrial Dynamics From the Uruguayan case to the Happiness economy RELATORE Prof. LUIGI MARENGO CANDIDATO ANDREA CASTELLANI Matr. 690601 CORRELATORE Prof. PAOLO GARONNA ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017/2018 2 INDEX INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: HAPPINESS AS A LIFE GOAL POLITICAL ECONOMICS MUST CONSIDER IN ITS DECISION-MAKING ............................................................................. 8 1.1 Happiness as a life goal ..................................................................................................... 8 1.2 The effect of institutional conditions on individual well-beings .................................... 9 1.2.1 The importance of the “Constitution” .................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Weighing the effect of a certain kind of Constitution ........................................... 12 1.2.3 How good governance affects well-being “above and beyond” income ............... 13 1.2.4 The real connection between Governance and Subjective Well-Being ............... 20 1.3 Measuring utilities and criteria to assess happiness and life satisfaction ................... 21 1.4 The Way Income Affects Happiness .............................................................................. 24 1.4.1 The effect of time on the income-happiness relation ............................................ -

1 a Guerra Da Cisplatina E O Início Da Formação Do Estado Imperial Brasileiro

1 A GUERRA DA CISPLATINA E O INÍCIO DA FORMAÇÃO DO ESTADO IMPERIAL BRASILEIRO Luan Mendes de Medeiros Siqueira (PPHR/ UFRRJ) Marcello Otávio Neri de Campos Basile Palavras- chave: Estado Nacional, Nação e Guerra da Cisplatina. Este trabalho é parte da minha pesquisa de mestrado que por sua vez tem como tema: As relações internacionais entre o Império do Brasil e as Províncias Unidas do Rio da Prata durante a Guerra da Cisplatina (1825- 1828). Procuramos compreender nesse presente estudo a consolidação do poder por parte deles sobre a região do Prata, já que era fundamental estruturar uma identidade na formação de tais Estados. A Guerra da Cisplatina, entretanto, pode ser considerada como o primeiro conflito em nível regional a ser resolvido pelo Brasil e Argentina em suas agendas de política externa e como um entrave também entre as suas áreas de litígio. Além disso, se quisermos nos aprofundar sobre a história da diplomacia entre tais países, elas terão suas origens majoritariamante nesse conflito. Daí, a necessidade de se pesquisar cada vez mais as relações internacionais de ambos os países nesse confronto. Neste trabalho, temos como referencial teórico o conceito de Relações Internacionais dos cientistas políticos Jean Baptiste Duroselle e Pierre Renouvin. Segundo eles, esse termo engloba uma série de elementos, dentre eles: territorialidade, condições demográficas, relevo, soberania e fronteiras políticas.1 A Guerra da Cisplatina pode-se inserir nesse campo teórico uma vez que o fator dos limites de fronteiras esteve intrinsecamente ligado à eclosão do conflito. A disputa pelo domínio da província Cisplatina, além de sua importância econômica, foi marcada também por um outro tópico componente do conceito de relações internacionais desses autores: Soberania. -

Conflictos Sociales Y Guerras De Independencia En La Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830

X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario, 2005. Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. Frega Ana. Cita: Frega Ana (2005). Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-006/16 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Xº JORNADAS INTERESCUELAS / DEPARTAMENTOS DE HISTORIA Rosario, 20 al 23 de septiembre de 2005 Título: Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio Mesa Temática Nº 2: Conflictividad, insurgencia y revolución en América del Sur. 1800-1830 Pertenencia institucional: Universidad de la República, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de Historia del Uruguay Autora: Frega, Ana. Profesora Agregada del Dpto. de Historia del Uruguay. Dirección laboral: Magallanes 1577, teléfono (+5982) 408 1838, fax (+5982) 408 4303 Correo electrónico: [email protected] 1 Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. -

Artigas, O Federalismo E As Instruções Do Ano Xiii

1 ARTIGAS, O FEDERALISMO E AS INSTRUÇÕES DO ANO XIII MARIA MEDIANEIRA PADOIN* As disputas entre as tendências centralistas-unitárias e federalistas, manifestadas nas disputas políticas entre portenhos e o interior, ou ainda entre províncias-regiões, gerou prolongadas guerras civis que estendeu-se por todo o território do Vice-Reino. Tanto Assunção do Paraguai quanto a Banda Oriental serão exemplos deste enfrentamento, como palco de defesa de propostas políticas federalistas. Porém, devemos ressaltar que tais tendências apresentavam divisões internas, conforme a maneira de interpretar ideologicamente seus objetivos, ou a forma pelo qual alcançá-los, ou seja haviam disputas de poder internamente em cada grupo, como nos chama a atenção José Carlos Chiaramonte (1997:216) : ...entre los partidarios del Estado centralizado y los de la unión confederal , pues exsiten evidencias de que en uno y en outro bando había posiciones distintas respecto de la naturaleza de la sociedad y del poder, derivadas del choque de concepciones historicamente divergentes, que aunque remetían a la común tradicón jusnaturalista que hemos comentado, sustentaban diferentes interpretaciones de algunos puntos fundamentales del Derecho Natural. Entre los chamados federales, era visible desde hacía muchos años la existencia de adeptos de antiguas tradiciones jusnaturalistas que admitian la unión confederal como una de las posibles formas de _______________ *Professora Associada ao Departamento de História e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria-UFSM; coordenadora do Grupo de Pesquisa CNPq História Platina: sociedade, poder e instituições. gobierno y la de quienes estaban al tanto de la reciente experiencia norteamericana y de su vinculación com el desarollo de la libertad y la igualdad política modernas . -

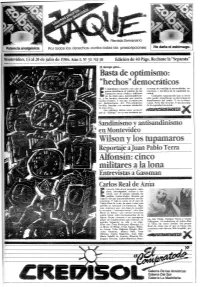

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Uruguay and Marijuana Legalization: a New Tupamaros Strategy ? by Fabio Bernabei Rome, 12 August 2013

Uruguay and Marijuana legalization: a new Tupamaros strategy ? by Fabio Bernabei Rome, 12 August 2013 The consequences of what’s happening in Uruguay are certainly not destined to remain within the boundaries of that South American nation and could have important consequences for the peoples all over the world. The Uruguay left-wing government have decided to pass a national law, for now in the Lower House by a narrow margin (50 votes against 46), pending the vote in the Senate, which unilaterally wipe out the obligation to respect the rules and controls set under UN Conventions on Drugs, legitimizing the cultivation and sale of cannabis.1 José Alberto Mujica Cordano, current head of State and Government, is the kingpin for this decisive turning-point against the population will who’s for 63% contrary to the legitimacy of cannabis.2 The President Mujica Cordano, at the beginning of the parliamentary process to ratify that unjustified violation of international law, refused to meet the delegation of the International Narcotics Control Board-INCB, an independent body that monitors implementation of the UN Conventions on Drugs by the signatory States such as Uruguay. The INCB, stated in an press release, in line with its mandate, “has always aimed at maintaining a dialogue with the Government of Uruguay on this issue, including proposing a mission to the country at the highest-level. The Board regrets that the Government of Uruguay refused to receive an INCB mission before the draft law was submitted to Parliament for deliberation”3. A one more (il)legal precedent disrespectful the International Community. -

The Plata Basin Example

Volume 30 Issue 1 Winter 1990 Winter 1990 Risk Perception in International River Basin Managemnt: The Plata Basin Example Jorge O. Trevin J. C. Day Recommended Citation Jorge O. Trevin & J. C. Day, Risk Perception in International River Basin Managemnt: The Plata Basin Example, 30 Nat. Resources J. 87 (1990). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol30/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. JORGE 0. TREVIN* and J.C. DAY** Risk Perception in International River Basin Management: The Plata Basin Example*** ABSTRACT Perceptionof the risk of multilateralcooperation has affected joint internationalaction for the integrateddevelopment of the PlataRiver Basin. The originsof sovereignty concerns amongArgentina,Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay are explored in terms of their his- torical roots. The role of risk in determining the character of the PlataBasin Treaty, and the ways in which risk was managedin order to reach cooperative agreements, are analyzed. The treaty incor- porates a number of risk management devices that were necessary to achieve internationalcooperation. The institutional system im- plemented under the treaty producedfew concrete results for almost two decades. Within the currentfavorable political environment in the basin, however, the structure already in place reopens the pos- sibility of further rapid integrative steps. INTRODUCTION Joint water development actions among the five states sharing the Plata Basin-Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay-have been dominated by two factors: the enormous potential benefits of cooperation, and long-standing international rivalries. -

URUGUAY: the Quest for a Just Society

2 URUGUAY: ThE QUEST fOR A JUST SOCiETY Uruguay’s new president survived torture, trauma and imprisonment at the hands of the former military regime. Today he is leading one of Latin America’s most radical and progressive coalitions, Frente Amplio (Broad Front). In the last five years, Frente Amplio has rescued the country from decades of economic stagnation and wants to return Uruguay to what it once was: A free, prosperous and equal society, OLGA YOLDI writes. REFUGEE TRANSITIONS ISSUE 24 3 An atmosphere of optimism filled the streets of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Montevideo as Jose Mujica assumed the presidency of Caribbean, Uruguay’s economy is forecasted to expand Uruguay last March. President Mujica, a former Tupamaro this year. guerrilla, stood in front of the crowds, as he took the Vazquez enjoyed a 70 per cent approval rate at the end oath administered by his wife – also a former guerrilla of his term. Political analysts say President Mujica’s victory leader – while wearing a suit but not tie, an accessory he is the result of Vazquez’s popularity and the economic says he will shun while in office, in keeping with his anti- growth during his time in office. According to Arturo politician image. Porzecanski, an economist at the American University, The 74-year-old charismatic new president defeated “Mujica only had to promise a sense of continuity [for the National Party’s Luis Alberto Lacalle with 53.2 per the country] and to not rock the boat.” cent of the vote. His victory was the second consecutive He reassured investors by delegating economic policy mandate for the Frente Amplio catch-all coalition, which to Daniel Astori, a former economics minister under the extends from radicals and socialists to Christian democrats Vazquez administration, who has built a reputation for and independents disenchanted with Uruguay’s two pragmatism, reliability and moderation. -

The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Economics Department Working Paper Series Faculty Scholarship and Creative Work 5-11-2011 The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet Stephen Meardon Bowdoin College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/econpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Meardon, Stephen, "The Free-Trade Doctrine and Commercial Diplomacy of Condy Raguet" (2011). Economics Department Working Paper Series. 1. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/econpapers/1 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Department Working Paper Series by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FREE-TRADE DOCTRINE AND COMMERCIAL DIPLOMACY OF CONDY RAGUET Stephen Meardon Department of Economics, Bowdoin College May 11, 2011 ABSTRACT Condy Raguet (1784-1842) was the first Chargé d’Affaires from the United States to Brazil and a conspicuous author of political economy from the 1820s to the early 1840s. He contributed to the era’s free-trade doctrine as editor of influential periodicals, most notably The Banner of the Constitution. Before leading the free-trade cause, however, he was poised to negotiate a reciprocity treaty between the United States and Brazil, acting under the authority of Secretary of State and protectionist apostle Henry Clay. Raguet’s career and ideas provide a window into the uncertain relationship of reciprocity to the cause of free trade.