The United States and the Uruguayan Cold War, 1963-1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Frentes Del Anticomunismo. Las Derechas En

Los frentes del anticomunismo Las derechas en el Uruguay de los tempranos sesenta Magdalena Broquetas El fin de un modelo y las primeras repercusiones de la crisis Hacia mediados de los años cincuenta del siglo XX comenzó a revertirse la relativa prosperidad económica que Uruguay venía atravesando desde el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A partir de 1955 se hicieron evidentes las fracturas del modelo proteccionista y dirigista, ensayado por los gobiernos que se sucedieron desde mediados de la década de 1940. Los efectos de la crisis económica y del estancamiento productivo repercutieron en una sociedad que, en la última década, había alcanzado una mejora en las condiciones de vida y en el poder adquisitivo de parte de los sectores asalariados y las capas medias y había asistido a la consolidación de un nueva clase trabajadora con gran capacidad de movilización y poder de presión. El descontento social generalizado tuvo su expresión electoral en las elecciones nacionales de noviembre de 1958, en las que el sector herrerista del Partido Nacional, aliado a la Liga Federal de Acción Ruralista, obtuvo, por primera vez en el siglo XX, la mayoría de los sufragios. Con estos resultados se inauguraba el período de los “colegiados blancos” (1959-1966) en el que se produjeron cambios significativos en la conducción económica y en la concepción de las funciones del Estado. La apuesta a la liberalización de la economía inauguró una década que, en su primera mitad, se caracterizó por la profundización de la crisis económica, una intensa movilización social y la reconfiguración de alianzas en el mapa político partidario. -

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗ Jennifer Alix-Garcia Laura Schechter Felipe Valencia Caicedo Oregon State University UW Madison University of British Columbia S. Jessica Zhu Precision Agriculture for Development April 5, 2021 Abstract Skewed sex ratios often result from episodes of conflict, disease, and migration. Their persistent impacts over a century later, and especially in less-developed regions, remain less understood. The War of the Triple Alliance (1864{1870) in South America killed up to 70% of the Paraguayan male population. According to Paraguayan national lore, the skewed sex ratios resulting from the conflict are the cause of present-day low marriage rates and high rates of out-of-wedlock births. We collate historical and modern data to test this conventional wisdom in the short, medium, and long run. We examine both cross-border and within-country variation in child-rearing, education, labor force participation, and gender norms in Paraguay over a 150 year period. We find that more skewed post-war sex ratios are associated with higher out-of-wedlock births, more female-headed households, better female educational outcomes, higher female labor force participation, and more gender-equal gender norms. The impacts of the war persist into the present, and are seemingly unaffected by variation in economic openness or ties to indigenous culture. Keywords: Conflict, Gender, Illegitimacy, Female Labor Force Participation, Education, History, Persistence, Paraguay, Latin America JEL Classification: D74, I25, J16, J21, N16 ∗First draft May 20, 2020. We gratefully acknowledge UW Madison's Graduate School Research Committee for financial support. We thank Daniel Keniston for early conversations about this project. -

Brazil Double Tax Treaty

Tax Insight Uruguay - Brazil Double Tax Treaty June 2019 In Brasilia, on June 7th the Authorities of the Brazilian and Uruguayan Government signed a tax treaty to avoid double taxation and prevent fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income and on capital (DTT) which substantially follows the OECD Model Tax Convention. This is a second step after the Agreement for the Exchange of Information (AEoI) that these countries signed back in 2012, which is still waiting ratification of the Brazilian Congress. The DTT is expected to enter into force in January 2020, provided Congress approval in both countries and the exchange of ratifying notes occur before the end of this calendar year. PwC Uruguay The DTT signed by Brazil and Uruguay follows in general terms, Business profits the OECD Model Tax Convention. Below we include a summary Profits of a company of a Contracting State are taxable only in of the most relevant provisions that the DTT contains. the State of residence, except when a PE in the country of source exists. If that case, its benefits may be taxed in the latter but only if they are attributable to that PE. Permanent Establishment (PE) Nevertheless, the protocol provides for a clause referring to It is included in PE definition building sites, constructions, and business profits, which establishes that in the event that the related activities when such work lasts for a period exceeding six State to which the tax authority is granted does not effectively months. According to Uruguayan domestic tax law, a levy taxes on said profits obtained by the company, those may construction PE is deemed to exist if the activities carried out be subject to taxes in the other Contracting State. -

From the Uruguayan Case to the Happiness Economy

Dipartimento di Impresa e Management Cattedra: International Macroeconomics and Industrial Dynamics From the Uruguayan case to the Happiness economy RELATORE Prof. LUIGI MARENGO CANDIDATO ANDREA CASTELLANI Matr. 690601 CORRELATORE Prof. PAOLO GARONNA ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017/2018 2 INDEX INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: HAPPINESS AS A LIFE GOAL POLITICAL ECONOMICS MUST CONSIDER IN ITS DECISION-MAKING ............................................................................. 8 1.1 Happiness as a life goal ..................................................................................................... 8 1.2 The effect of institutional conditions on individual well-beings .................................... 9 1.2.1 The importance of the “Constitution” .................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Weighing the effect of a certain kind of Constitution ........................................... 12 1.2.3 How good governance affects well-being “above and beyond” income ............... 13 1.2.4 The real connection between Governance and Subjective Well-Being ............... 20 1.3 Measuring utilities and criteria to assess happiness and life satisfaction ................... 21 1.4 The Way Income Affects Happiness .............................................................................. 24 1.4.1 The effect of time on the income-happiness relation ............................................ -

LA SACRALIZACIÓN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL Y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HISTÓRICA Y LA JUSTICIA EN EL URUGUAY POSDICTATORIAL América Latina Hoy, Vol

América Latina Hoy ISSN: 1130-2887 [email protected] Universidad de Salamanca España RONIGER, Luis LA SACRALIZACIÓN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HISTÓRICA y LA JUSTICIA EN EL URUGUAY POSDICTATORIAL América Latina Hoy, vol. 61, agosto, 2012, pp. 51-78 Universidad de Salamanca Salamanca, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=30824379003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto LA SACRALIZACIóN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HIStóRICA y LA jUStICIA EN EL URUGUAy POSDICtAtORIAL The Sanctification of National Consensus and Struggles over Historical Memory and Justice in Post-Dictatorial Uruguay Luis RONIGER Wake Forest University, Estados Unidos * [email protected] BIBLID [1130-2887 (2012) 61, 51-78] Fecha de recepción: 24 de enero del 2012 Fecha de aceptación: 19 de junio del 2012 RESUMEN: Este trabajo se propone analizar el peso relativo de los poderes institucionales y la sociedad civil dentro de la constelación de fuerzas que bregaron por definir políticas de jus - ticia transicional y configurar la memoria histórica de la sociedad uruguaya y que, en una larga serie de parciales intentos, eventualmente abrieron nuevos espacios de institucionalidad para el establecimiento tardío de responsabilidad legal y rendición de cuentas por las violaciones a los derechos humanos cometidas en el Uruguay en el marco de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave : justicia transicional, memoria histórica, derechos humanos, impunidad y ren - dición de cuentas. -

The Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations

Volume 41, Number 3, January 2011 assp rt PThe Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations Inside... Nixon, Allende, and the White House Tapes Roundtable on Dennis Merrill’s Negotiating Paradise Teaching Diplomatic History to Diplomats ...and much more! Passport The Newsletter of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations Editorial Office: Mershon Center for International Security Studies 1501 Neil Avenue Columbus OH 43201 [email protected] 614-292-1681 (phone) 614-292-2407 (fax) Executive Director Peter L. Hahn, The Ohio State University Editor Mitchell Lerner, The Ohio State University-Newark Production Editor Julie Rojewski, Michigan State University Editorial Assistant David Hadley, The Ohio State University Cover Photo President Nixon walking with Kissinger on the south lawn of the White House, 08/10/1971. ARC Identifier 194731/ Local Identifier NLRN-WHPO-6990-18A. Item from Collection RN-WHPO: White House Photo Office Collection (Nixon Administration), 01/20/1969-08/09/1974. Editorial Advisory Board and Terms of Appointment Elizabeth Kelly Gray, Towson University (2009-2011) Robert Brigham, Vassar College (2010-2012) George White, Jr., York College/CUNY (2011-2013) Passport is published three times per year (April, September, January), by the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, and is distributed to all members of the Society. Submissions should be sent to the attention of the editor, and are acceptable in all formats, although electronic copy by email to [email protected] is preferred. Submis- sions should follow the guidelines articulated in the Chicago Manual of Style. Manuscripts accepted for publication will be edited to conform to Passport style, space limitations, and other requirements. -

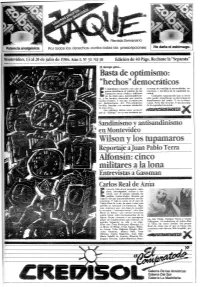

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Uruguay and Marijuana Legalization: a New Tupamaros Strategy ? by Fabio Bernabei Rome, 12 August 2013

Uruguay and Marijuana legalization: a new Tupamaros strategy ? by Fabio Bernabei Rome, 12 August 2013 The consequences of what’s happening in Uruguay are certainly not destined to remain within the boundaries of that South American nation and could have important consequences for the peoples all over the world. The Uruguay left-wing government have decided to pass a national law, for now in the Lower House by a narrow margin (50 votes against 46), pending the vote in the Senate, which unilaterally wipe out the obligation to respect the rules and controls set under UN Conventions on Drugs, legitimizing the cultivation and sale of cannabis.1 José Alberto Mujica Cordano, current head of State and Government, is the kingpin for this decisive turning-point against the population will who’s for 63% contrary to the legitimacy of cannabis.2 The President Mujica Cordano, at the beginning of the parliamentary process to ratify that unjustified violation of international law, refused to meet the delegation of the International Narcotics Control Board-INCB, an independent body that monitors implementation of the UN Conventions on Drugs by the signatory States such as Uruguay. The INCB, stated in an press release, in line with its mandate, “has always aimed at maintaining a dialogue with the Government of Uruguay on this issue, including proposing a mission to the country at the highest-level. The Board regrets that the Government of Uruguay refused to receive an INCB mission before the draft law was submitted to Parliament for deliberation”3. A one more (il)legal precedent disrespectful the International Community. -

The Plata Basin Example

Volume 30 Issue 1 Winter 1990 Winter 1990 Risk Perception in International River Basin Managemnt: The Plata Basin Example Jorge O. Trevin J. C. Day Recommended Citation Jorge O. Trevin & J. C. Day, Risk Perception in International River Basin Managemnt: The Plata Basin Example, 30 Nat. Resources J. 87 (1990). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol30/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. JORGE 0. TREVIN* and J.C. DAY** Risk Perception in International River Basin Management: The Plata Basin Example*** ABSTRACT Perceptionof the risk of multilateralcooperation has affected joint internationalaction for the integrateddevelopment of the PlataRiver Basin. The originsof sovereignty concerns amongArgentina,Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay are explored in terms of their his- torical roots. The role of risk in determining the character of the PlataBasin Treaty, and the ways in which risk was managedin order to reach cooperative agreements, are analyzed. The treaty incor- porates a number of risk management devices that were necessary to achieve internationalcooperation. The institutional system im- plemented under the treaty producedfew concrete results for almost two decades. Within the currentfavorable political environment in the basin, however, the structure already in place reopens the pos- sibility of further rapid integrative steps. INTRODUCTION Joint water development actions among the five states sharing the Plata Basin-Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay-have been dominated by two factors: the enormous potential benefits of cooperation, and long-standing international rivalries. -

Vi Brazil As a Latin American Political Unit

VI BRAZIL AS A LATIN AMERICAN POLITICAL UNIT I. PHASES OF BRAZILIAN HISTORY is almost a truism to say that interest in the history of a I' country is in proportion to the international importance of it as a nation. The dramatic circumstances that might have shaped that history are of no avail to make it worth knowing; the actual or past standing of the country and its people is thus the only practical motive. According to such an interpretation of historical interest, I may say that the international importance of Brazil seems to be growing fast. Since the Great War, many books on South America have been published in the United States, and abundant references to Brazil may be found in all of them. Should I have to mention any of the recent books, I would certainly not forget Herman James's Brazil after a Century,' Jones's South Amer- ica,' for the anthropogeographic point of view, Mary Wil- liams's People and Politics oj Latin Arneri~a,~the books of Roy Nash, J. F. Normano, J. F. Rippy, Max Winkler, and others. Considering Brazil as a South American political entity, it is especially the historical point of view that I purpose to interpret. Therefore it may be convenient to have a pre- liminary general view of the story of independent Brazil, 'See reference, Lecture V, p. 296. IC. F. Jones, South America (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1930). Wary W. Williams, The People and Politics of Latin America (Boston: Ginn & CO., 1930). 312 Brazil as a Political Unit 313 emphasizing the characteristic features of the different pe- riods. -

URUGUAY: the Quest for a Just Society

2 URUGUAY: ThE QUEST fOR A JUST SOCiETY Uruguay’s new president survived torture, trauma and imprisonment at the hands of the former military regime. Today he is leading one of Latin America’s most radical and progressive coalitions, Frente Amplio (Broad Front). In the last five years, Frente Amplio has rescued the country from decades of economic stagnation and wants to return Uruguay to what it once was: A free, prosperous and equal society, OLGA YOLDI writes. REFUGEE TRANSITIONS ISSUE 24 3 An atmosphere of optimism filled the streets of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Montevideo as Jose Mujica assumed the presidency of Caribbean, Uruguay’s economy is forecasted to expand Uruguay last March. President Mujica, a former Tupamaro this year. guerrilla, stood in front of the crowds, as he took the Vazquez enjoyed a 70 per cent approval rate at the end oath administered by his wife – also a former guerrilla of his term. Political analysts say President Mujica’s victory leader – while wearing a suit but not tie, an accessory he is the result of Vazquez’s popularity and the economic says he will shun while in office, in keeping with his anti- growth during his time in office. According to Arturo politician image. Porzecanski, an economist at the American University, The 74-year-old charismatic new president defeated “Mujica only had to promise a sense of continuity [for the National Party’s Luis Alberto Lacalle with 53.2 per the country] and to not rock the boat.” cent of the vote. His victory was the second consecutive He reassured investors by delegating economic policy mandate for the Frente Amplio catch-all coalition, which to Daniel Astori, a former economics minister under the extends from radicals and socialists to Christian democrats Vazquez administration, who has built a reputation for and independents disenchanted with Uruguay’s two pragmatism, reliability and moderation. -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001).