The Plata Basin Example

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecos Del Constitucionalismo Gaditano En La Banda Oriental Del Uruguay 11

Ecos del Constitucionalismo gaditano en la Banda Oriental del Uruguay 11 ECOS DEL CONSTITUCIONALISMO GADITANO EN LA BANDA ORIENTAL DEL URUGUAY AN A FREG A NOV A LES UNIVERSID A D DE L A REPÚBLIC A (UR U G ua Y ) RESUMEN El artículo explora las influencias de los debates y el texto constitucional aprobado en Cádiz en 1812 en los territorios de la Banda Oriental del Uruguay, durante dos dé- cadas que incluyen la resistencia de los “leales españoles” en Montevideo, el proyecto confederal de José Artigas, la incorporación a las monarquías constitucionales de Por- tugal y Brasil y la formación de un Estado independiente. Plantea cómo las discusiones doctrinarias sobre monarquía constitucional o república representativa, soberanía de la nación o soberanía de los pueblos, y centralismo o federalismo reflejaban antiguos con- flictos jurisdiccionales y diferentes posturas frente a la convulsión del orden social. PALABRAS CLAVE: Montevideo, Provincia Oriental, Provincia Cisplatina, Sobe- ranía, Constitución. ABSTRACT This article explores the influences of the debates and constitutional text approved in Cadiz in 1812 on Banda Oriental del Uruguay territories, during two decades that include the resistance of the “loyal Spaniards” in Montevideo, the confederate project of José Artigas, the incorporation to the constitutional monarchies of Portugal and Brazil and the creation of an independent State. Moreover, it poses how the doctrinaire TROCADERO (24) 2012 pp. 11-25 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25267/Trocadero.2012.i24.01 12 Ana Frega Novales discussions about constitutional monarchy or representative republic, sovereignty of the nation or sovereignty of the peoples, and centralism or federalism, reflected long- standing jurisdictional conflicts and different stances regarding the upheaval of the social order. -

LA SACRALIZACIÓN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL Y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HISTÓRICA Y LA JUSTICIA EN EL URUGUAY POSDICTATORIAL América Latina Hoy, Vol

América Latina Hoy ISSN: 1130-2887 [email protected] Universidad de Salamanca España RONIGER, Luis LA SACRALIZACIÓN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HISTÓRICA y LA JUSTICIA EN EL URUGUAY POSDICTATORIAL América Latina Hoy, vol. 61, agosto, 2012, pp. 51-78 Universidad de Salamanca Salamanca, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=30824379003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto LA SACRALIZACIóN DEL CONSENSO NACIONAL y LAS PUGNAS POR LA MEMORIA HIStóRICA y LA jUStICIA EN EL URUGUAy POSDICtAtORIAL The Sanctification of National Consensus and Struggles over Historical Memory and Justice in Post-Dictatorial Uruguay Luis RONIGER Wake Forest University, Estados Unidos * [email protected] BIBLID [1130-2887 (2012) 61, 51-78] Fecha de recepción: 24 de enero del 2012 Fecha de aceptación: 19 de junio del 2012 RESUMEN: Este trabajo se propone analizar el peso relativo de los poderes institucionales y la sociedad civil dentro de la constelación de fuerzas que bregaron por definir políticas de jus - ticia transicional y configurar la memoria histórica de la sociedad uruguaya y que, en una larga serie de parciales intentos, eventualmente abrieron nuevos espacios de institucionalidad para el establecimiento tardío de responsabilidad legal y rendición de cuentas por las violaciones a los derechos humanos cometidas en el Uruguay en el marco de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave : justicia transicional, memoria histórica, derechos humanos, impunidad y ren - dición de cuentas. -

1 a Guerra Da Cisplatina E O Início Da Formação Do Estado Imperial Brasileiro

1 A GUERRA DA CISPLATINA E O INÍCIO DA FORMAÇÃO DO ESTADO IMPERIAL BRASILEIRO Luan Mendes de Medeiros Siqueira (PPHR/ UFRRJ) Marcello Otávio Neri de Campos Basile Palavras- chave: Estado Nacional, Nação e Guerra da Cisplatina. Este trabalho é parte da minha pesquisa de mestrado que por sua vez tem como tema: As relações internacionais entre o Império do Brasil e as Províncias Unidas do Rio da Prata durante a Guerra da Cisplatina (1825- 1828). Procuramos compreender nesse presente estudo a consolidação do poder por parte deles sobre a região do Prata, já que era fundamental estruturar uma identidade na formação de tais Estados. A Guerra da Cisplatina, entretanto, pode ser considerada como o primeiro conflito em nível regional a ser resolvido pelo Brasil e Argentina em suas agendas de política externa e como um entrave também entre as suas áreas de litígio. Além disso, se quisermos nos aprofundar sobre a história da diplomacia entre tais países, elas terão suas origens majoritariamante nesse conflito. Daí, a necessidade de se pesquisar cada vez mais as relações internacionais de ambos os países nesse confronto. Neste trabalho, temos como referencial teórico o conceito de Relações Internacionais dos cientistas políticos Jean Baptiste Duroselle e Pierre Renouvin. Segundo eles, esse termo engloba uma série de elementos, dentre eles: territorialidade, condições demográficas, relevo, soberania e fronteiras políticas.1 A Guerra da Cisplatina pode-se inserir nesse campo teórico uma vez que o fator dos limites de fronteiras esteve intrinsecamente ligado à eclosão do conflito. A disputa pelo domínio da província Cisplatina, além de sua importância econômica, foi marcada também por um outro tópico componente do conceito de relações internacionais desses autores: Soberania. -

Conflictos Sociales Y Guerras De Independencia En La Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830

X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario, 2005. Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. Frega Ana. Cita: Frega Ana (2005). Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-006/16 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Xº JORNADAS INTERESCUELAS / DEPARTAMENTOS DE HISTORIA Rosario, 20 al 23 de septiembre de 2005 Título: Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio Mesa Temática Nº 2: Conflictividad, insurgencia y revolución en América del Sur. 1800-1830 Pertenencia institucional: Universidad de la República, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de Historia del Uruguay Autora: Frega, Ana. Profesora Agregada del Dpto. de Historia del Uruguay. Dirección laboral: Magallanes 1577, teléfono (+5982) 408 1838, fax (+5982) 408 4303 Correo electrónico: [email protected] 1 Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. -

Artigas, O Federalismo E As Instruções Do Ano Xiii

1 ARTIGAS, O FEDERALISMO E AS INSTRUÇÕES DO ANO XIII MARIA MEDIANEIRA PADOIN* As disputas entre as tendências centralistas-unitárias e federalistas, manifestadas nas disputas políticas entre portenhos e o interior, ou ainda entre províncias-regiões, gerou prolongadas guerras civis que estendeu-se por todo o território do Vice-Reino. Tanto Assunção do Paraguai quanto a Banda Oriental serão exemplos deste enfrentamento, como palco de defesa de propostas políticas federalistas. Porém, devemos ressaltar que tais tendências apresentavam divisões internas, conforme a maneira de interpretar ideologicamente seus objetivos, ou a forma pelo qual alcançá-los, ou seja haviam disputas de poder internamente em cada grupo, como nos chama a atenção José Carlos Chiaramonte (1997:216) : ...entre los partidarios del Estado centralizado y los de la unión confederal , pues exsiten evidencias de que en uno y en outro bando había posiciones distintas respecto de la naturaleza de la sociedad y del poder, derivadas del choque de concepciones historicamente divergentes, que aunque remetían a la común tradicón jusnaturalista que hemos comentado, sustentaban diferentes interpretaciones de algunos puntos fundamentales del Derecho Natural. Entre los chamados federales, era visible desde hacía muchos años la existencia de adeptos de antiguas tradiciones jusnaturalistas que admitian la unión confederal como una de las posibles formas de _______________ *Professora Associada ao Departamento de História e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria-UFSM; coordenadora do Grupo de Pesquisa CNPq História Platina: sociedade, poder e instituições. gobierno y la de quienes estaban al tanto de la reciente experiencia norteamericana y de su vinculación com el desarollo de la libertad y la igualdad política modernas . -

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

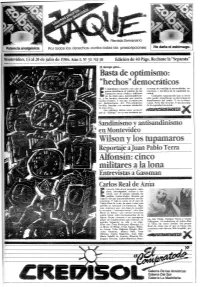

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Vi Brazil As a Latin American Political Unit

VI BRAZIL AS A LATIN AMERICAN POLITICAL UNIT I. PHASES OF BRAZILIAN HISTORY is almost a truism to say that interest in the history of a I' country is in proportion to the international importance of it as a nation. The dramatic circumstances that might have shaped that history are of no avail to make it worth knowing; the actual or past standing of the country and its people is thus the only practical motive. According to such an interpretation of historical interest, I may say that the international importance of Brazil seems to be growing fast. Since the Great War, many books on South America have been published in the United States, and abundant references to Brazil may be found in all of them. Should I have to mention any of the recent books, I would certainly not forget Herman James's Brazil after a Century,' Jones's South Amer- ica,' for the anthropogeographic point of view, Mary Wil- liams's People and Politics oj Latin Arneri~a,~the books of Roy Nash, J. F. Normano, J. F. Rippy, Max Winkler, and others. Considering Brazil as a South American political entity, it is especially the historical point of view that I purpose to interpret. Therefore it may be convenient to have a pre- liminary general view of the story of independent Brazil, 'See reference, Lecture V, p. 296. IC. F. Jones, South America (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1930). Wary W. Williams, The People and Politics of Latin America (Boston: Ginn & CO., 1930). 312 Brazil as a Political Unit 313 emphasizing the characteristic features of the different pe- riods. -

The United States and the Uruguayan Cold War, 1963-1976

ABSTRACT SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 In the early 1960s, Uruguay was a beacon of democracy in the Americas. Ten years later, repression and torture were everyday occurrences and by 1973, a military dictatorship had taken power. The unexpected descent into dictatorship is the subject of this thesis. By analyzing US government documents, many of which have been recently declassified, I examine the role of the US government in funding, training, and supporting the Uruguayan repressive apparatus during these trying years. Matthew Ford May 2015 SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 by Matthew Ford A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Matthew Ford Thesis Author Maria Lopes (Chair) History William Skuban History Lori Clune History For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in part or in its entirety must be obtained from me. -

Dossier | Nuevos Enfoques Sobre La Ocupación Luso-Brasileña En La

Dossier | Nuevos enfoques sobre la ocupación luso- brasileña en la Provincia Oriental (1817-1830) ISSN sección Dossier 2618-415x Dossier | Nuevos enfoques sobre la ocupación luso- brasileña en la Provincia Oriental (1817-1830) Nicolás Duffau (Instituto de Historia-FHCE/UdelaR) y Pablo Ferreira (Instituto de Historia-FHCE/UdelaR) El Virreinato del Río de la Plata inició un paulatino proceso de desintegración a partir de la crisis imperial y el comienzo del período revolucionario en 1810. En ese marco, Montevideo se consolidó hasta 1814 como una de las principales ciudades que adhirió al Consejo de Regencia. A su vez, las fuerzas revolucionarias tuvieron dos componentes: por un lado, los ejércitos enviados por los gobiernos “insurgentes” formados en Buenos Aires, y por otro las fuerzas que se organizaron en la campaña oriental y que encontraron un referente en la figura de José Gervasio Artigas. La movilización que lideró el artiguismo canalizó variadas adhesiones, reclamos y aspiraciones, que involucraron a las elites urbanas y rurales, pero también a los sectores populares. La participación de estos últimos favoreció el estallido de conflictos vinculados a la apropiación de la tierra, los recursos naturales, las disputas jurisdiccionales y la discusión sobre la situación de esclavizados y amerindios. Entre 1815 e inicios de 1817 los orientales controlaron el conjunto de la Provincia y alcanzaron a extender su propuesta federal a diversas provincias de la región litoral de los ríos Uruguay y Paraná conformando lo que se denominó como el Sistema de los Pueblos Libres, una alianza ofensiva defensiva que enfrentó las propuestas centralistas de Buenos Aires y que reivindicó la soberanía particular de los pueblos. -

Academic Offer 2018

Course Catalog 2018 ENOPU Academic Offer 2018 Montevideo, November 2017 1 Course Catalog 2018 ENOPU Content Content ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 I. WELCOME FROM THE DIRECTOR OF ENOPU ...................................................................................... 3 II. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 4 II.1 Mission ................................................................................................................................................ 4 II.2 Historical review.................................................................................................................................. 4 II.3 Institutional Organization Chart.......................................................................................................... 6 II.4 ENOPU´s Code of Conduct .................................................................................................................. 7 III. COURSES ............................................................................................................................................. 8 III.1 United Nations Military Experts on Mission (UNMEM) ...................................................................... 8 III.2 UN PKO National Investigations Officers Training Course (UN PKO NIOTC) ...................................... -

Christianity and the Struggle for Human Rights in the Uruguayan Laïcité

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Dynamic Secularisms: Christianity and the Struggle for Human Rights in the Uruguayan Laïcité by Lucía Cash MA Thesis presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Linell Cady, Chair Christopher Duncan Daniel Schugurensky Carolyn Warner ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 ABSTRACT From 1973 to 1984 the people of Uruguay lived under a repressive military dictatorship. During that time, the Uruguayan government violated the Human Rights of its opponents and critics through prolonged imprisonment in inhumane conditions without trial, physical and psychological torture, disappearance, and a negation of freedom of speech, thought and congregation. In this project, I argue that these violations of Human Rights committed by the military dictatorship added urgency to the rethinking by religious individuals of the Uruguayan model of secularism, the laïcité, and the role that their theology required them to play in the “secular” world. Influenced by the Liberation Theology movement, Catholic and Protestant leaders simultaneously made use of and challenged the secularization model in order to carve a space for themselves in the struggle for the protection of Human Rights. Furthermore, I will argue that due to the Uruguayan system of partitocracy, which privileges political parties as the main voices in public matters, Uruguay still carries this history of Human Rights violations on its back. Had alternative views been heard in the public sphere, this thorny history might have been dealt with in a fairer manner. -

Discursive Processes of Intergenerational Transmission of Recent History Also by Mariana Achugar

Discursive Processes of Intergenerational Transmission of Recent History Also by Mariana Achugar WHAT WE REMEMBER: The Construction of Memory in Military Discourse (2008) ‘Mariana Achugar has written a powerful and solid book in which she gives voice to new generations of Uruguayan youth from Montevideo and rural Tacuarembó, who enter the public debate about the contested traumatic past of recent dictatorship. As Mariana emphasizes in her work, “the goal of intergenerational transmission of the recent past is not only to remember, but to understand”, and this is precisely what youth manifested to be interested in, because understanding their past enables them to construct their national and civic identities. Mariana expands the theoretical and methodological approaches in discourse analysis and focuses on the circulation and reception of texts. She exam- ines intertextuality and resemiotization in recontextualized practices, for analyzing what youth know about the dictatorship and how they learn about it. In doing so, Mariana reveals the complexity of this cir- culation of meanings about the past through popular culture, family conversations and history classroom interactions in school contexts. We learn that the youth, as active members of society, construct the past of the dictatorship through both; schematic narratives that are avail- able in the public sphere, and from their own elaborations grounded on the materials available in the community. This is a highly relevant and much needed book for scholars interested in memory and critical discourse studies.’ – Teresa Oteíza, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile ‘Memory scholars agree that the inter-generational transmission of col- lective memories is key to shaping the future, and others have noted that Uruguay is in the vanguard of using the school to transmit historical memories of the recent past to children who did not live it themselves, but no one has studied this process so closely or so well as Mariana Achugar .