Cultural Background and Meaning of Ta Moko - Māori Tattoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between the Margin and the Text

BETWEEN THE MARGIN AND THE TEXT He kanohi kē to Te Pākehā-Māori Huhana Forsyth A thesis submitted to AUT University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2013 Faculty of Te Ara Poutama i Table of Contents Attestation.............................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements............................................................................... vii Abstract.................................................................................................. viii Preface.................................................................................................... ix Chapter One: Background to the study.............................................. 1 i. Researcher’s personal story......................................................... 2 ii. Emergence of the topic for the study............................................ 3 iii. Impetus for the study.................................................................... 8 iv. Overall approach to the study....................................................... 9 Chapter Two: The Whakapapa of Pākehā-Māori……………………… 11 i. Pre-contact Māori society and identity......................................... 11 ii. Whakapapa of the term Pākehā-Māori……………………………. 13 iii. Socio-historical context................................................................. 18 iv. Pākehā-Māori in the socio-historical context................................ 22 v. Current socio-cultural context...................................................... -

Savage Skins: the Freakish Subject of Tattooed Beachcombers

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Online Kunapipi Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 4 2005 Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers Annie Werner Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Werner, Annie, Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers, Kunapipi, 27(1), 2005. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol27/iss1/4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers Abstract When the first beachcombers started to return to Europe from the Pacific, their indigenously tattooed bodies were the subject of both fascination and horror. While some exhibited themselves in circuses, sideshows, museums and fairs, others published narratives of their experiences, and these narratives cumulatively came to constitute the genre of beachcomber narratives, which had been emerging steadily since the early 1800s. As William Cummings points out, the process of tattooing or being tattooed was often a ‘central trope’ (7) in the beachcomber narratives. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol27/iss1/4 11 ANNIE WERNER Savage Skins: The Freakish Subject of Tattooed Beachcombers* When the first beachcombers started to return to Europe from the Pacific, their indigenously tattooed bodies were the subject of both fascination and horror. While some exhibited themselves in circuses, sideshows, museums and fairs, others published narratives of their experiences, and these narratives cumulatively came to constitute the genre of beachcomber narratives, which had been emerging steadily since the early 1800s. -

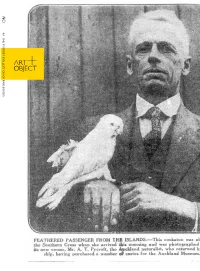

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Wellesley Legenda

^M^ 'vi|^^ '^ m ^*\ ^2^fc s. y^- '^^-i^TTT- Z_. ^^^^^^—^ y,j^9^. Tnn fcnGnNDA (UEl.LE3Ln^T COI^mcie PH^I^I^MED I^q THE **^nNIOK (^h^33 y To Our Esteemed Ancestor NOAH Tl)is I^eijenda i.s Dedicated with the ^Ympathetic (Appreciation of the Class of '^ Sarah Bixby. Elizahetli Hardee. Helen Drake. Marion Anderson. Eliz.abelli M. McGuire. Levinia D. Smith. Jane Williams. Emily Shultz. Grace O. Edwards. Marv H. Holmes- "WE LOOK BEFORE AND AFTER' H. B. HarJce E- ,\1. AlcGuirL-. The Beast. ( Academic Council (?) L. D. Smith. S. H. Bi.xby. ] Advertising Agent (?) M. W. Anderson. J. Williams. ' Our Consciences (?) M. H. Holmes. E. B. Shultz. O- O. Edwards. LEGENDA BOARD. 'AND SIGH FOR WHAT IS HOT." ^, _> — M-oM ^foiUi^ vMr^iPuu ci).5 ^z ih^^-p^^ 4/u^a^ .^U^f.^gr i/^. Preface. ~7 --- T'lIEN the present Board first undertook the task of publishing; a Legenda for the 111 Class of '94, it was with a very definite idea of what a Legenda should be. ^J-^ We believed that it was primarilv intended as a memor\' book for the students, wherein they might find the record of one vear of College life; and that, like all memory books, it should deal principally with the lighter side of that life, — the pleasant ex- periences and amusing incidents, rather than the academic work and intellectual growth. In our attempt to embody this idea in concrete form, we have, of course, n:elwithmany practical difficulties. One of the matters which have been most perplexing to us is that of personalities. -

Bibliotheca Polynesiana”

Skrifter fra Universitetsbiblioteket i Oslo 5 Svein A.H. Engelstad Catalogue of the “Kroepelien collection” or “Bibliotheca Polynesiana”, owned by the Oslo University Library, deposited at the Kon Tiki Museum in Oslo Catalogue of the “Kroepelien collection” or “Bibliotheca Polynesiana”, owned by the Oslo University Library, deposited at the Kon Tiki Museum in Oslo Svein A.H. Engelstad Universitetsbiblioteket i Oslo 2008 © Universitetsbiblioteket i Oslo 2008 ISSN 1504-9876 (trykt) ISSN 1890-3614 (online) ISBN 978-82-8037-017-4 (trykt) ISBN 978-82-8037-018-1 (online) Ansvarlig redaktør: Bente R. Andreassen Redaksjon: Jan Engh (leder) Bjørn Bandlien Per Morten Bryhn Anne-Mette Vibe Trykk og innbinding: AIT e-dit 2008 Produsert i samarbeid med Unipub AS Det må ikke kopieres fra denne boka i strid med åndsverkloven eller med andre avtaler om kopiering inngått med Kopinor, interesseorgan for rettighetshavere til åndsverk. Introduction The late Bjarne Kroepelien was a great collector of books and other printed material from the Polynesia, and specifically the Tahiti. Kroepelien stayed at Tahiti for about a year in 1918 and 1919. He was married there with a Tahitian woman. He was also adopted as a son of the chief in Papenoo, Teriieroo, and given his name. During his stay at Tahiti, the island was hit by the Spanish flu and about forty percent of the inhabitants lost their lives, among them his dear wife. Kroepelien organised the health services of the victims and the burials of the deceased, he was afterwards decorated with the French Order of Merit. He went back to Norway, but his heart was lost to Tahiti, but he chose never to return to his lost paradise, and he never remarried. -

Foreigners.Pdf

Cover (front and back): Wild Africans Tamed by His Name ca. 1895 Title inscribed verso 151 by 199 mm. Gelatin silver print Right British School English Camel Corps, Sudan 1884/5 Title inscribed verso 305 by 390 mm (shown cropped) MICHAEL GRAHAM-STEWART Pencil, watercolour 2 0 1 1 1/ 2/ L. Chagny Henry James Pidding (1797-1864) Les Rois en Exil. Presentations Royales. The Fair Penitent Amis, tous amis 1830 Title and signature imprinted. Verso with Signed lower right. Title taken from the L. Chagny, dessin-edit., 44, r. Michelet, Alger, mezzotint by William Giller after Pidding postal stamps and inscribed with address 305 by 255 mm and message Oil on panel 95 by 138 mm Seen in isolation this image of an African Lithograph, postcard suffering a medieval punishment in the This apparently charming postcard, mailed English countryside appears to be a within Algeria in 1906, is a reminder of an harmless oddity. However, the same intense period of French colonial expansion. model is shown in the companion painting The three monarchs shown had all been by Pidding, entitled Massa out, Sambo forcibly exiled to villas in or around Algiers. werry dry, in which a servant is liberally They all died there. partaking of his absent master’s liquor. The group on the left includes the Both paintings were exhibited in the annual distinctively hatted figure of Behanzin Society of British Artists show at Suffolk (1841-1906), King of Dahomey. After a long Street (in 1830 and 1828) and both were campaign he had surrendered to a French engraved, thus reaching a wide audience. -

Before We Get Started Today I Think We Better Address the Elephant in the Room

Before we get started today I think we better address the elephant in the room. If you are listening to this at time of release, that is April 2020, the world has kinda gone bananas with the COVID-19 virus pandemic causing all sorts of havoc across the globe. As some of you will be aware, I live in New Zealand and as of right now we have been in lockdown for a week and that will be the case for at least another three. I’m sure you have all been getting those silly emails from companies you interacted with once 10 years ago telling you how their combating the virus, god knows I have, so I don’t want to harp on too much but the fact of the matter is this: HANZ will still continue through the lockdown to the best of my ability. At this stage I have enough content to get us through to about end of May, start of June however after that I’m still formulating what I will do should I not be able to access research materials, which is a very real possibility. Additionally this podcast like many out there is funded in large part by two groups, myself and our fantastic Patrons. Unfortunately my ability to pump as much funds into this project as I have in the past has reduced fairly significantly due to the current situation. This doesn’t mean I’m going to be out on the streets or anything, as I said HANZ will still continue as much as I can make it and all for free, all I ask is that if you have considered in the past to donate by becoming a Patron or buying merch and you have the means to do so, now would be the time. -

Tattooing in Colonial Literature Anne Elizabeth Werner University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Curating inscription: the legacy of textual exhibitions of tattooing in colonial literature Anne Elizabeth Werner University of Wollongong Werner, Anne Elizabeth, Curating inscription: the legacy of textual exhibitions of tattooing in colonial literature, PhD thesis, School of English Literatures, Philosophy and Languages, University of Wollongong,2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/785 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/785 Curating Inscription: The Legacy of Textual Exhibitions of Tattooing in Colonial Literature A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Anne Elizabeth Werner BA School of English Literatures, Philosophy and Languages 2008 1 Certification I, Anne Elizabeth Werner, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of English Literatures, Philosophy and Languages, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Anne Elizabeth Werner 25 July 2008 2 Contents List of Illustrations 4 Abstract 6 Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 9 Chapter One: 22 Curating Inscription Chapter Two: 95 Savage Printers, Apostate Fugitives and Unheard-of Sufferings Chapter Three: 95 ―… as we belonged to them, we should wear their ki-e-chook‘: The Captivities of Olive Oatman Chapter Four: 148 ―A chief, or a cutlet, in Polynesia‖?: Herman Melville‘s Uneasy Journey. Chapter Five: 189 Moko and Identity:The Changing Face of the Language of the Skin Conclusion: Towards an Appropriate Appropriation 234 Bibliography 238 3 List of Illustrations Introduction: ―Omai a Native of Ulaietea… Brought into England in 1774 by Tobias Furneauz Esq. -

Representations of Pakeha-Maori in the Works of James Cowan

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. IMAGES OF PAKEHA-MAORI A Study of the Representation of Pakeha-Maori by Historians of New Zealand From Arthur Thomson (1859) to James Belich (1996) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Waikato Trevor William Bentley University of Waikato 2007 Abstract This thesis investigates how Pakeha-Maori have been represented in New Zealand non-fiction writing during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The chronological and textual boundaries range from Arthur Thomson’s seminal history The Story of New Zealand (1859) to James Belich’s Making Peoples (1996). It examines the discursive inventions and reinventions of Pakeha-Maori from the stereotypical images of the Victorian era to modern times when the contact zone has become a subject of critical investigation and a sign of changing intellectual dynamics in New Zealand and elsewhere. -

Joshua Mewburn – Accidental New Zealand Pioneer of 1833 and Pākehā-Māori

The Journal of Genealogy and Family History, Vol. 2, No. 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.24240/23992964.2018.1234514 Joshua Mewburn – accidental New Zealand pioneer of 1833 and Pākehā-Māori Ian G. Macdonald Abstract: There are Mewburns in New Zealand today, but they are not related (other than perhaps back in the fourteenth century) to the first Mewburn to come Received: 8 December 2017 Accepted: 12 January 2018 to the islands. He was Joshua Mewburn (1817–c.1855). Joshua arrived in New KEYWORDS: New Zealand; Pākehā; Māori; Zealand first in 1833, an early, pre-colonial date so of particular historical interest. slavery; cannibalism; moko; tribal warfare; He returned to England in 1841, then shipped back again to New Zealand in 1842 Musket Wars; migration; silversmithing; colonization; pre-colonial New Zealand; on the Jane Gifford, the first ship to land official colonists, and is believed even- Jane Gifford tually to have died there. We know something of his exploits and life through court records and newspaper items, and through the journal of a voyage. It seems that he became what is known as a Pākehā-Māori. Joshua was robbed and abandoned in 1833 at the Bay of Islands, then taken in by Māori tribes where he may have lived for up to eight years, unusually, having his face tattooed during that time. He eventually returned to living with the Māori, but that last phase of his life is more obscure. This paper seeks to unravel some of his life and doings, and determine his place in early New Zealand colonial history. -

History Time Line of Napier and Hawke's

HISTORY TIME LINE OF NAPIER AND HAWKE’S BAY A partial timeline of Napier and Hawke’s Bay 1769-1974. Port Ahuriri 1866 by Charles Decimus Barraud, 1822-1897: A view from Bluff Hill, Napier, looking north down to Westshore and Port Ahuriri. There are houses on a spit of land surrounded by water and further low- lying islands without houses. A steam ship and a number of sailing ships can be seen in the harbor. Ref: D-040-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/32199839 Introduction: Ngāti Kahungunu trace their origins to the Tākitimu waka, which arrived in Aotearoa from Rarotonga around 1100-1200 AD. Tamatea Ariki Nui, the captain of Tākitimu, settled in Tauranga, and is buried on top of Mauao, called Mount Maunganui today. Tamatea Ariki Nui had a son called Rongokako, and he had a son called Tamatea Pokai Whenua Pokai Moana, which means “Tamatea explorer of land and sea.” It is from Tamatea Pokai Whenua Pokai Moana that we have the longest place name, located at Porongahau – “Taumatawhakatangihangakōauauatamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronuku pokaiwhenuakitānatahu” where Tamatea Pokai Whenua Pokai Moana played a flute to his lover. It is the son of Tamatea Pokai Whenua Pokai Moana named Kahungunu that Ngāti Kahungunu comes from. Kahungunu travelled widely and eventually settled on the East Coast. His grandson Rakaihikuroa, migrated with his son Taraia, their families and followers, from Nukutaurua on the Māhia Peninsula to Heretaunga (Hawke’s Bay area). Eventually, Heretaunga was brought under the control of his people, who became the first Ngāti Kahungunu as we know it today in Hawke’s Bay. -

'The Key-Stone of the District': the Crown Purchase of the Mahia Block

'The Key-stone of the District': The Crown Purchase of the Mahia Block, 1864 Elizabeth Cox Waitangi Tribunal 1999 Contents INTRODUCTION 3 MAP ONE: MAHIA PENINSULA CROWN PURCHASE AND NATIVE LAND COURT BLOCK DIVISIONS 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE MAHIA PENINSULA BEFORE 1864 7 MAORI OCCUPATION OF THE PENINSULA 7 THE MUSKET WARS AND THE REFUGEES ON THE PENINSULA, 1820-1840 14 EARLY MAORI·PAKEHA CONTACT 16 CHAPTER TWO: CROWN PURCHASE OF THE MAHIA BLOCK, 1864 26 THE NEGOTIATIONS AND SALE OF THE MAHIA BLOCK 31 THE DISPUTES BEGIN 33 CHAPTER THREE: TWENTIETH CENTURY PROTESTS 45 SIM COMMISSION, 1927 47 NATIVE LAND COURT INVESTIGATION, 1938 49 ROYAL COMMISSION, 1948 52 THE FATE OF THE MAHIA RESERVES 59 KlNIKINI 59 KAIUKU 61 OTHER LAND RETURNED TO IHAKA WHAANGA 64 CONCLUSION 67 APPENDIX ONE: CONTEMPORARY MAPS 72 MAP Two: SKETCH MAP A ITA CHED TO THE MAHIA BLOCK DEED, 1864 73 MAP THREE: MAPAITACHED TO THEROYAL COMMISSION REPORT, 1948 74 MAP FOUR: MAP OF VARIOUS SECTIONS WITHIN MAHIA TOWNSHIP, c.1935 75 MAP FIVE: MAP OF KINIKINI, FROM THE CROIVNGRANT, 1871 76 MAP SIX: MAPOFKAIWAITAU, FROMTHECROIVNGRANT, 1872 77 APPENDIX TWO: MARIA BLOCK DEED 78 APPENDIX THREE: LOCKE TO MCLEAN LETTERS 1864 - 1865 81 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 2 Introduction It was expected that the sale of this block would open the way for much larger purchases, as was afterwards the case. The Mahia may be considered as the key-stone of the district.! This report discusses the Crown purchase of the Mahia Block, signed on 20 October 1864. The Mahia Block was the first land purchased by the Crown in the Mahia Peninsula and Wairoa district.