Race Relations in the Contact Period. 1769-1830

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources • Standards Correlation • Glossary The Museum gratefully acknowledges the sdnat.org/whales County of San Diego and the City of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture. ESSENTIAL Questions What is a whale? Many populations remain endangered. National and intergovernmental organizations collaborate to establish Whales are mammals; they breathe air and live their and enforce regulations that protect whale populations, whole lives in water. People often use the word “whale” to and some are showing recovery from whaling. The most refer to large species like sperm and humpback whales, effective whale protection programs involve the whole life but dolphins and porpoises are also whales since they’re cycle, from monitoring migration routes to conserving all members of the order Cetacea. Cetaceans evolved important breeding habitats and feeding grounds. from hoofed animals that walked on four legs, and their closest living relatives are hippos. Living whales are divided into two groups: baleen whales (Mysticeti, or How do scientists study whales? filter feeders) and toothed whales (Odontoceti, which Many kinds of scientists — conservation biologists, hunt larger prey). Whales inhabit all of the world’s major paleontologists, taxonomists, anatomists, ecologists, oceans, and even some of its rivers. Some species are geneticists — work together to learn more about these widespread, while others are localized. Many migrate magnificent creatures. Fossil specimens provide a long distances, with some species feeding in polar glimpse back some 50 million years, to whales’ waters and mating in warmer ones during the winter land-dwelling ancestors. -

Between the Margin and the Text

BETWEEN THE MARGIN AND THE TEXT He kanohi kē to Te Pākehā-Māori Huhana Forsyth A thesis submitted to AUT University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2013 Faculty of Te Ara Poutama i Table of Contents Attestation.............................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements............................................................................... vii Abstract.................................................................................................. viii Preface.................................................................................................... ix Chapter One: Background to the study.............................................. 1 i. Researcher’s personal story......................................................... 2 ii. Emergence of the topic for the study............................................ 3 iii. Impetus for the study.................................................................... 8 iv. Overall approach to the study....................................................... 9 Chapter Two: The Whakapapa of Pākehā-Māori……………………… 11 i. Pre-contact Māori society and identity......................................... 11 ii. Whakapapa of the term Pākehā-Māori……………………………. 13 iii. Socio-historical context................................................................. 18 iv. Pākehā-Māori in the socio-historical context................................ 22 v. Current socio-cultural context...................................................... -

The New Zealand Cetacea

r- tl^Ðn**t t Fisheries Research Bulletin No. r (New Series) The New Zealand Cetacea By D. E. Gaskin FISHERTES RESEÄRCH DIVISION, NEW ZEALAND MÁ.RTNB DEPÁ.RTMENT _l THE NE'üØ ZEALAND CETACEA , ,,i! ''it{ Pholograph fui D. E. Gaskin. Frontispiece : A blue whale (Balaenoþtera tnusculus) being flensed on the deck of the FF Southern Venlurt:r in the Weddell Sea in February t962. Fisheries Research Bulletin No. r (New Series) The New Zealand Cetacea By D. E" Gaskin* Fisheries Research Division, Marine Department, Wellington, New Zealand * Present address: Depattment of Zooloe¡ Massey lJnivetsity, Palmetston Noth FISHERIES RESE..q.RCH DIVISION, NE\Ø ZEAIAND MÁ.RINE DEP,{.RTMENT Edited byJ W McArthur Published by the New Zealand Marine Department, 1968 I{. [,. OWDN, GOVI':RNMENT PRINTDR. WELLINGTON. NEW ZEALAND-19ti3 FORE\TORD OvBn the past decade there has been a continued interest in the Iarge and small whales of New Zealand. This activity in the Marine Department and elsewhere followed earlier intensive work on the humpback whale in Victoria University of Wellington. As the humpback industry declined attention turned to the sperm whale. Substantial field studies of this species in local waters were made by the Marine Department. At the same time there has been a steady increase in the data available on strandings of the smaller whales. The circumstances make it appropriate to provide a handbook of the whale species fo-und in New Zealand waters. This bulletin is presented as a review of the available taxonomic and ecological data and not as a systematic revision of the group. -

The Impact of Tourism on the Maori Community in Kaikoura

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive The Impact of Tourism on the Māori Community in Kaikoura Aroha Poharama Researcher for Ngati Kuri, Ngai Tahu Merepeka Henley Researcher in the Te Whare Tikaka Māori me ka Mahi Kairakahaua Ailsa Smith Lecturer, Division of Environmental Monitoring and Design, Kaupapa Mātauraka Māori Lincoln University. John R Fairweather Senior Research Officer in the Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, Lincoln University. [email protected] David G Simmons Reader in Tourism, Human Sciences Division, Lincoln University. [email protected] September 1998 ISSN 1174-670X Tourism Research and Education Centre (TREC) Report No. 7 Contents LIST OF TABLES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v GLOSSARY vi SUMMARY viii CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND, RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND METHOD.............. 1 1.1 Introduction........................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background Information .................................................................... 2 1.3 Research Objectives, Methods and Approach ................................... 4 1.4 Conclusion ......................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND TO THE MĀORI COMMUNITY OF KAIKOURA................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Introduction........................................................................................ 9 2.2 An -

Indigenous Peoples' Participation in the Nineteenth Century Fur Trade in Canada and Whaling Industry in New Zealand

University of Alberta Re-Conceptualizing the Traditional Economy: Indigenous Peoples’ Participation in the Nineteenth Century Fur Trade in Canada and Whaling Industry in New Zealand by Leanna Parker A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Indigenous Economic History Department of Rural Economy and the Faculty of Native Studies ©Leanna Parker Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author’s prior written permission. Examining Committee Frank Tough, Faculty of Native Studies Naomi Krogman, Department of Rural Economy Jane Samson, Department of History Cheryl McWatters, Alberta School of Business Arthur J. Ray, Professor Emeritus, History Department, University of British Columbia Re-Conceptualizing the Traditional Economy: Indigenous Peoples’ Participation in the Nineteenth Century Fur Trade in Canada and Whaling Industry in New Zealand Abstract Contemporary resource use on Indigenous lands is not often well understood by the general public. In particular, there is a perception that “traditional” and commercial resource use are mutually exclusive, and therefore there is often an assumption that Indigenous communities are abandoning their traditional economy when they participate in the commercial sector of the larger regional economy. -

The Rise of Modern International Order

George Lawson The rise of modern international order Book section (Accepted refereed) Original citation: Originally published in: Baylis, John, Smithson, Steve and Owens, Patricia, (eds.) The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations. Oxford, UK : Oxford University Press, 2016 , pp. 37-51 © 2016 The Authors This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/68644/ Available in LSE Research Online: December 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. CH 2-The Rise of Modern International Order Chapter 2 The Rise of Modern International Order GEORGE LAWSON <start feature> Framing Questions When did modern international order emerge? To what extent was the emergence of modern international order shaped by the experience of the West? Is history important to understanding contemporary world politics? <end feature> Reader’s guide This chapter explores the rise of modern international order. -

Tess Brosnan

FINDING HOPE ON A PLANET IN CRISIS University of Otago Finding Hope on a Planet in Crisis: Combining Citizen Science and Tourism Tess Brosnan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Communication Centre for Science Communication, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June, 2014 FINDING HOPE ON A PLANET IN CRISIS 2 Abstract This thesis is produced in conjunction with the documentary film Whale Chasers (a copy of this film is included in the back cover of this thesis). The film follows the progress of the annual Cook Strait Whale Project, a New Zealand-based citizen science project for conservation biology. The written thesis explores the origins, popularity and success of the contemporary citizen science movement, and its role in conservation biology and informal science education. It also explores the physical and mental health benefits of participation (a key component of the citizen science movement), and the potential for citizen science to inspire hope in times of ecological crisis. The new fields of hopeful tourism and positive psychology in tourism are then explored for their parallels with citizen science, with discussion of how the movements might be merged to create citizen science tourism experiences. A survey of local travellers and international tourists to New Zealand provides a complementary empirical investigation, assessing current interest and thus practical potential for citizen-science based tourism. FINDING HOPE ON A PLANET IN CRISIS 3 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Wynsome Brosnan, who turned me into an avid bird watcher, showed me the importance of always having hope, and encouraged me to go chasing whales. -

2018 IID Meeting, Orlando, Florida

May 16-19, 2018 MEETING PROGRAM Rosen Shingle Creek Resort Orlando, Florida www.IID2018.org IID 2018 MEETING IID 2018 Program Chairs and Final Reviewers ESDR - Program Chairs JSID - Program Chairs SID - Program Chairs Michel Gilliet, MD Manabu Fujimoto, MD Nicole Ward, PhD Matthias Schmuth, MD Manabu Ohyama, MD/PhD Victoria Werth, MD ESDR – Final Reviewers JSID – Final Reviewers SID – Final Reviewers Hervé Bachelez, MD/PhD Riichiro Abe, MD/PhD Vladimir Botchkarev, MD/PhD Leopold Eckhart, PhD Manabu Fujimoto, MD Spiro Getsios, PhD Menno de Rie, MD/PhD Minoru Hasegawa, MD Daniel Kaplan, MD/PhD Bernhard Homey, MD Hironobu Ihn, MD/PhD Ethan Lerner, MD/PhD David Kelsell, PhD Kenji Kabashima, MD/PhD Lloyd Miller, MD/PhD Lionel Larue, PhD Takuro Kanekura, MD/PhD Peggy Myung, MD/PhD Caterina Missero, PhD Norito Katoh, PhD Marjana Tomic-Canic, PhD Edel O’Toole, PhD Tatsuyoshi Kawamura, MD/PhD Kevin Wang, MD/PhD Ralf Paus, MD/PhD Akiharu Kubo, MD/PhD Nicole Ward, PhD Sirkku Peltonen, MD/PhD Akimichi Morita, MD/PhD Victoria Werth, MD Neil Rajan, MD/PhD Manabu Ohyama, MD/PhD Martin Steinhoff, MD/PhD Ryuhei Okuyama, MD/PhD Marta Szell, DSc Tamio Suzuki, MD/PhD Thomas Werfel, MD Katsuto Tamai, MD/PhD Peter Wolf, MD Akemi Yamamoto, MD/PhD European Society for Japanese Society for Society for Investigative Dermatological Research Investigative Dermatology Dermatology Rue Cingria 7, Geneva 5F, 4-1-4 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 526 Superior Avenue East, Suite 340 Switzerland, 1205 113-0033, Japan Cleveland, Ohio 44114, USA Tel: +41 22 321 48 90 Tel: +81-3-3830-0068 Tel: +01 216-579-9300 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdr.org Web: www.jsid.org Web: www.sidnet.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The organizers of IID 2018 gratefully acknowledge the many exhibitors and sponsors whose attendance has helped make this meeting possible. -

Savage Skins: the Freakish Subject of Tattooed Beachcombers

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Online Kunapipi Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 4 2005 Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers Annie Werner Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Werner, Annie, Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers, Kunapipi, 27(1), 2005. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol27/iss1/4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Savage skins: The freakish subject of tattooed beachcombers Abstract When the first beachcombers started to return to Europe from the Pacific, their indigenously tattooed bodies were the subject of both fascination and horror. While some exhibited themselves in circuses, sideshows, museums and fairs, others published narratives of their experiences, and these narratives cumulatively came to constitute the genre of beachcomber narratives, which had been emerging steadily since the early 1800s. As William Cummings points out, the process of tattooing or being tattooed was often a ‘central trope’ (7) in the beachcomber narratives. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol27/iss1/4 11 ANNIE WERNER Savage Skins: The Freakish Subject of Tattooed Beachcombers* When the first beachcombers started to return to Europe from the Pacific, their indigenously tattooed bodies were the subject of both fascination and horror. While some exhibited themselves in circuses, sideshows, museums and fairs, others published narratives of their experiences, and these narratives cumulatively came to constitute the genre of beachcomber narratives, which had been emerging steadily since the early 1800s. -

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

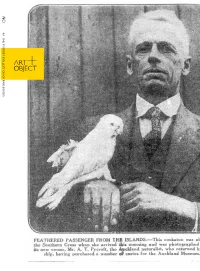

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Wellesley Legenda

^M^ 'vi|^^ '^ m ^*\ ^2^fc s. y^- '^^-i^TTT- Z_. ^^^^^^—^ y,j^9^. Tnn fcnGnNDA (UEl.LE3Ln^T COI^mcie PH^I^I^MED I^q THE **^nNIOK (^h^33 y To Our Esteemed Ancestor NOAH Tl)is I^eijenda i.s Dedicated with the ^Ympathetic (Appreciation of the Class of '^ Sarah Bixby. Elizahetli Hardee. Helen Drake. Marion Anderson. Eliz.abelli M. McGuire. Levinia D. Smith. Jane Williams. Emily Shultz. Grace O. Edwards. Marv H. Holmes- "WE LOOK BEFORE AND AFTER' H. B. HarJce E- ,\1. AlcGuirL-. The Beast. ( Academic Council (?) L. D. Smith. S. H. Bi.xby. ] Advertising Agent (?) M. W. Anderson. J. Williams. ' Our Consciences (?) M. H. Holmes. E. B. Shultz. O- O. Edwards. LEGENDA BOARD. 'AND SIGH FOR WHAT IS HOT." ^, _> — M-oM ^foiUi^ vMr^iPuu ci).5 ^z ih^^-p^^ 4/u^a^ .^U^f.^gr i/^. Preface. ~7 --- T'lIEN the present Board first undertook the task of publishing; a Legenda for the 111 Class of '94, it was with a very definite idea of what a Legenda should be. ^J-^ We believed that it was primarilv intended as a memor\' book for the students, wherein they might find the record of one vear of College life; and that, like all memory books, it should deal principally with the lighter side of that life, — the pleasant ex- periences and amusing incidents, rather than the academic work and intellectual growth. In our attempt to embody this idea in concrete form, we have, of course, n:elwithmany practical difficulties. One of the matters which have been most perplexing to us is that of personalities. -

The John Allen House and Tryon's Palace: Icons of the North Carolina

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY The John Allen House and Tryon’s Palace: Icons of the North Carolina Regulator Movement A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By H. Gilbert Bradshaw LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA 2020 Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iii Chapter 1: “A Well-Documented Picture of North Carolina History” ..................................... 1 Chapter 2: “Valley of Humility Between Two Mountains of Conceit” ................................. 28 Chapter 3: “The Growing Weight of Oppression Which We Lye Under” ............................ 48 Chapter 4: “Great Elegance in Taste and Workmanship” ...................................................... 70 Chapter 5: “We Have Until Very Recently Neglected Our Historical Sites” ....................... 101 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 133 ii “For there are deeds that should not pass away, And names that must not wither.” – Plaque in St. Philip’s Church Brunswick Town, North Carolina iii Abstract A defining feature of North Carolina is her geography. English colonists who founded the first settlements in the east adapted their old lifestyles to their new environs, and as a result, a burgeoning planter and merchant class emerged throughout the Tidewater and coastal regions. This eastern gentry replicated the customs, manners,