The John Allen House and Tryon's Palace: Icons of the North Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol

FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 Q Orange County Bound for Congress 2019 Q Spain and the American Revolution Q Battle of Alamance Q James Tilton: 1st U.S. Army Surgeon General Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 24 Above, the Gen. David Humphreys Chapter of the Connecticut Society participated in the 67th annual Fourth of July Ceremony at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, 20 Connecticut; left, the Tilton Mansion, now the University and Whist Club. 8 2019 SAR Congress Convenes 13 Solid Light Reception 20 Delaware’s Dr. James Tilton in Costa Mesa, California The Prison Ship Martyrs Memorial Membership 22 Arizona’a First Grave Marking 14 9 State Society & Chapter News SAR Travels to Scotland 24 10 2018 SAR Annual Conference 16 on the American Revolution 38 In Our Memory/New Members 18 250th Series: The Battle 12 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Alamance 46 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. -

92Nd Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh

92nd Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh Saturday, May 16 Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-One Degrees Awarded 1980-81 CORRECTED COPY DEGREES CONFERRED A corrected issue of undergraduate and graduate degrees including degrees awarded June 25, 1980, August 6, 1980, and December 16, 1980. Musical Program EXERCISES OF GRADUATION May 16, 1981 COMMENCEMENT BAND CONCERT: 8:45 AM. William Neal Reynolds Coliseum Egmont Overture Beethoven Chester Schuman TheSinfonians ......................... Williams America the Beautiful Ward-Dragon PROCESSIONAL: 9:15 A.M. March Processional Grundman RECESSIONAL: University Grand March ................................................... Goldman NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT BAND Donald B. Adcock, Conductor The Alma Mater Words by: Music by: ALVIN M. FOUNTAIN, ’23 BONNIE F. NORRIS, JR., ’23 Where the winds of Dixie softly blow o'er the fields of Caroline, There stands ever cherished N. C. State, as thy honored shrine. So lift your voices; Loudly sing from hill to oceanside! Our hearts ever hold you, N. C. State, in the folds of our love and pride. Exercises of Graduation William Neal Reynolds Coliseum Joab L. Thomas, Chancellor Presiding May 16, 1981 PROCESSIONAL, 9:15 am. Donald B. Adcock Conductor, North Carolina State University Commencement Band theTheProcessionalAudience is requested to remain seated during INVOCATION DougFox Methodist Chaplain, North Carolina State University ADDRESS Dr. Frank Rhodes President, Cornell University CONFERRING OF DEGREES .......................... ChancellorJoab L. Thomas Candidates for baccalaureate degrees presented by presentedDeans of Schools.by DeanCandidatesof the Graduatefor advancedSchool degrees ADDRESS TO FELLOW GRADUATES ........................... Terri D. Lambert Class of1981 ANNOUNCEMENT OF GOODWIFE GOODHUSBAND DIPLOMAS ................................ Kirby Harriss Jones ANNOUNCEMENT OF OUTSTANDING Salatatorian TEACHER AWARDS ...................................... -

An Archaeological Inventory of Alamance County, North Carolina

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA Alamance County Historic Properties Commission August, 2019 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA A SPECIAL PROJECT OF THE ALAMANCE COUNTY HISTORIC PROPERTIES COMMISSION August 5, 2019 This inventory is an update of the Alamance County Archaeological Survey Project, published by the Research Laboratories of Anthropology, UNC-Chapel Hill in 1986 (McManus and Long 1986). The survey project collected information on 65 archaeological sites. A total of 177 archaeological sites had been recorded prior to the 1986 project making a total of 242 sites on file at the end of the survey work. Since that time, other archaeological sites have been added to the North Carolina site files at the Office of State Archaeology, Department of Natural and Cultural Resources in Raleigh. The updated inventory presented here includes 410 sites across the county and serves to make the information current. Most of the information in this document is from the original survey and site forms on file at the Office of State Archaeology and may not reflect the current conditions of some of the sites. This updated inventory was undertaken as a Special Project by members of the Alamance County Historic Properties Commission (HPC) and published in-house by the Alamance County Planning Department. The goals of this project are three-fold and include: 1) to make the archaeological and cultural heritage of the county more accessible to its citizens; 2) to serve as a planning tool for the Alamance County Planning Department and provide aid in preservation and conservation efforts by the county planners; and 3) to serve as a research tool for scholars studying the prehistory and history of Alamance County. -

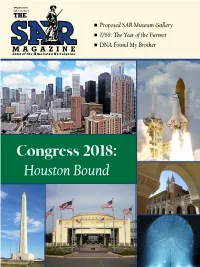

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

An Historical Overviw of the Beaufort Inlet Cape Lookout Area of North

by June 21, 1982 You can stand on Cape Point at Hatteras on a stormy day and watch two oceans come together in an awesome display of savage fury; for there at the Point the northbound Gulf Stream and the cold currents coming down from the Arctic run head- on into each other, tossing their spumy spray a hundred feet or better into the air and dropping sand and shells and sea life at the point of impact. Thus is formed the dreaded Diamond Shoals, its fang-like shifting sand bars pushing seaward to snare the unwary mariner. Seafaring men call it the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Actually, the Graveyard extends along the whole of the North Carolina coast, northward past Chicamacomico, Bodie Island, and Nags Head to Currituck Beach, and southward in gently curving arcs to the points of Cape Lookout and Cape Fear. The bareribbed skeletons of countless ships are buried there; some covered only by water, with a lone spar or funnel or rusting winch showing above the surface; others burrowed deep in the sands, their final resting place known only to the men who went down with them. From the days of the earliest New World explorations, mariners have known the Graveyard of the Atlantic, have held it in understandable awe, yet have persisted in risking their vessels and their lives in its treacherous waters. Actually, they had no choice in the matter, for a combination of currents, winds, geography, and economics have conspired to force many of them to sail along the North Carolina coast if they wanted to sail at all!¹ Thus begins David Stick’s Graveyard of the Atlantic (1952), a thoroughly researched, comprehensive, and finely-crafted history of shipwrecks along the entire coast of North Carolina. -

FALL/WINTER 2020/2021 – Tuesday Schedule Morning Class: 10:00 – 12:00 and Afternoon Class: 1:30 – 3:30

FALL/WINTER 2020/2021 – Tuesday Schedule Morning Class: 10:00 – 12:00 and Afternoon Class: 1:30 – 3:30 September 29, 2020 The Magic of Audrey Janna Trout (Extra session added to our regular schedule, to practice using Zoom.) The essence of chic and a beautiful woman, Audrey Hepburn, brought a certain “magic” quality to the screen. Synonymous with oversized sunglasses and the little black dress, many are unaware of the hardships she endured while growing up in Nazi-occupied Holland. Starring in classic movies such as Sabrina, My Fair Lady, and of course, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Audrey Hepburn brought effortless style and grace to the silver screen. Following the many Zoom training opportunities offered in the last two weeks of September, let’s put our training to the test! The Technology Team recommended we conduct the first zoom class without a live presenter so we can ensure that everything is working correctly to set us up for a successful semester. Below is the format of our first LIFE@ Elon class on Zoom – enjoy this documentary about the one and only Audrey Hepburn! Open Class On Tuesday mornings, you will receive an email with a link for the class. (If the presenter has a handout, we will attach it to the email.) Twenty minutes before the start of class, we will have the meeting open so you can click on the link to join. Kathryn Bennett, the Program Coordinator, will be there to greet members as they are logging on, and Katie Mars, the Technology Specialist, will be present, as well. -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

North Carolina General Assembly 1979 Session

NORTH CAROLINA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 1979 SESSION RESOLUTION 21 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1128 A JOINT RESOLUTION DEDICATING PROPERTIES AS PART OF THE STATE NATURE AND HISTORIC PRESERVE. Whereas, Article XIV, Section 5 of the North Carolina Constitution authorizes the dedication of State and local government properties as part of the State Nature and Historic Preserve, upon acceptance by resolution adopted by a vote of three fifths of the members of each house of the General Assembly; and Whereas, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the State Nature and Historic Preserve Dedication Act, Chapter 443, 1973 Session Laws to prescribe the conditions and procedures under which properties may be specially dedicated for the purposes enumerated by Article XIV, Section 5 of the North Carolina Constitution; and Whereas, the 1973 General Assembly sought to declare units of the State park system and certain historic sites as parts of the State Nature and Historic Preserve by adoption of Resolution 84 of the 1973 Session of the General Assembly; and Whereas, the effective date of 1973 Session Laws, Resolution 84 was May 10, 1973, while the effective date of Article XIV, Section 5, of the North Carolina Constitution and Chapter 443 of the 1973 Session Laws was July 1, 1973, thereby making Resolution 84 ineffective to confer the intended designation to the properties cited therein; and Whereas, the General Assembly desires to reaffirm its intention to accept certain properties enumerated in Resolution 84 of the 1973 General Assembly and to add certain properties acquired since the adoption of said Resolution as part of the State Nature and Historic Preserve; and Whereas, the Council of State pursuant to G.S. -

The Rose Hill Wreck, the Project Also Served As a Field Classroom for Training Participants in Basic Underwater Archaeological Techniques

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 TABLE OF FIGURES __________________________________________________ 4 Dedicated to the Memory of ______________________________________________ 7 INTRODUCTION______________________________________________________ 8 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING _________________________________________ 10 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND_________________________________________ 12 UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND___________________ 26 DESCRIPTION OF WORK ____________________________________________ 30 Survey_____________________________________________________________ 31 Wreck Examination _________________________________________________ 33 VESSEL CONSTRUCTION ____________________________________________ 35 Keel_______________________________________________________________ 35 Stem/Apron ________________________________________________________ 37 Deadwood and Sternpost _____________________________________________ 37 Rising Wood________________________________________________________ 37 Floors _____________________________________________________________ 38 Futtocks ___________________________________________________________ 39 Keelson ____________________________________________________________ 39 Ceiling_____________________________________________________________ 40 Planking ___________________________________________________________ 40 Fasteners __________________________________________________________ 42 Bilge Pump_________________________________________________________ 42 Rudder ____________________________________________________________ -

Calendar of North Carolina Papers at London Board of Trade, 1729 - 177

ENGLISH RECORDS -1 CALENDAR OF NORTH CAROLINA PAPERS AT LONDON BOARD OF TRADE, 1729 - 177, Accession Information! Schedule Reference t NON! Arrangement t Chronological Finding Aid prepared bye John R. Woodard Jr. Date t December 12, 1962 This volume was the result of a resolution (N.C. Acts, 1826-27, p.85) pa~sed by the General Assembly of North Carolina, Febuary 9, 1821. This resolution proposed that the Governor of North Carolina apply to the British government for permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Co- lonial history of North Carolina. This application was submitted through the United states Ninister to the Court of St. James, Albert Gallatin. Gallatin vas giTen permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Colonial history of North Carolina. Gallatin found documents in the Board of Trade Office and the "state Paper uffice" (which was the common depository for the archives of the Home, Foreign, and Colonial departments) and made a list of them. Gallatin's list and letters from the Secretary of the Board of Trade and the Foreign Office were sent to Governor H.G. Burton, August 25, 1821 and then vere bound together to form this volume. A lottery to raise funds for the copying of the documents was authorized but failed. The only result 6"emS to have been for the State to have published, An Index to Colonial Docwnents Relative to North Carolina, 1843. [See Thornton, }1ary Lindsay, OffIcial Publications of 'l'heColony and State of North Carolina, 1749-1939. p.260j Indexes to documentS relative to North Carolina during the coloDl81 existence of said state, now on file in the offices of the Board of Trade and state paper offices in London, transmitted in 1827, by Mr. -

A Brief History of the Granville District and Land Grants

Appendix C: A Brief History of the Granville District and Land Grants Before 1729, the British kings repeatedly granted territory in the American colonies to individuals or small groups. Most of the territory that was to become the Carolinas, Georgia and part of Florida was originally granted by King Charles II to repay a political debt to a group of eight of his supporters who would be known as the Lords Proprietors, investing them not only with property but also with gubernatorial authority to administer it. The Province of Carolina1 was a proprietary colony from 1663 to 1729. Most of the Lords Proprietors began granting land in the Carolinas in 1669, but, unfortunately, most of the land records for the proprietary period have been lost. Indirect rule by the Lords Proprietors eventually fell out of favor as the English Sovereigns sought to concentrate their power and authority, and the colonies were converted to crown colonies, governed by officials appointed by the King. In 1729, seven of the eight heirs to the original Lords Proprietors sold their proprietary shares back to King George II, and North Carolina became a royal colony. The eighth share belonged to John Carteret,2 who refused to sell his share to the crown. Carteret’s share consisted of holdings in what are now North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. In 1742, the king's Privy Council agreed to Carteret's request to exchange these holdings for a continuous area in North Carolina. The northern boundary was to be the Virginia- North Carolina border (36° 30')—the only boundary in the entire province that had been fixed— and the southern line at 35° 34'. -

Aftermath of the Battle of Alamance

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > ANCHOR > Revolutionary North Carolina (1763-1790) > The Regulators: Introduction > Aftermath of the Battle of Alamance Aftermath of the Battle of Alamance [1] Share it now! A few weeks after the Battle of Alamance in May 1771, an account of the battle and its aftermath made its way to various newspapers throughout the colonies, including as far north as the Boston Gazette. The account included included report of the casualties, which may have been exaggerated, and a call for a reward for the capture of the outlaws, Herman Husband, Rednap Howell, and William Butler. Below is a transcription of the Boston Gazette account. It includes annotations for historical commentary and definitions. Newbern (North Carolina) June 7. Since our last, the Hon. Samuel Cornell, Esq., returned home from our Troops in Orange County, and brings a certain Account of the Regulators being entirely broken and dispersed [2], and that near 13 or 1400 of them have laid down their arms, taken the Oaths ofA llegiance [3] to his Majesty, and returned to their Habitations [4] in Peace. His Excellency the Governor, after the Battle, marched into the Plantations of Husband, Hunter, and several others of the outlawed Chiefs of the Regulators, and laid them waste; they having most of them escaped from the Battle, and are since fled. A reward of 1000 Acres of Land, and 100 Dollars, is offered by his Excellency for Husband, Hunter, Butler, and Rednap Howell, and several of the Regulators have been permitted to go in Quest of them, on leaving their Children Hostages.