The Not-So-Artful Dodger: the Mccourt- Selig Battle and the Powers of the Commissioner of Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

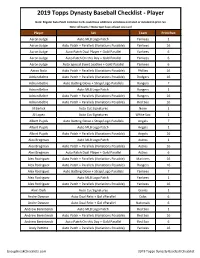

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

Designated Hitters and Subesquent Team Scoring

DESIGNATED HITTERS AND SUBESQUENT TEAM SCORING PERFORMANCE IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE BY SARAH E. CHO DR. HOLMES FINCH – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2020 2 ABSTRACT RESEARCH PAPER: Designated Hitters and Subsequent Team Scoring Performance in Major League Baseball STUDENT: Sarah E. Cho DEGREE: Master of Science COLLEGE: Teachers College DATE: July 2020 PAGES: 27 The Designated Hitter (DH) rule in Major League Baseball (MLB) is a topic of great debate. In the National League (NL), all players take a turn at bat. However, in the American League (AL), a DH usually bats for the pitcher. MLB pitchers typically do not have strong batting averages. The DH rule was created to increase a team’s offense. This study looked at whether there is an apparent difference between the AL and the NL. In theory, a DH will lead to more hits, more runs, and therefore a higher scoring game. This study looked at the average runs per game and total home runs for the AL and NL during the 1998 through 2018 regular seasons. Since the assumptions of parametric multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were not met, a nonparametric analysis was used. The permutation test for multivariate means results showed an apparent difference between the two leagues (p < .05). A quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) was used as a follow up test and showed home runs as the variable driving the difference between the two leagues. Therefore, the AL has better scoring performance than the NL. -

Hardball Diplomacy and Ping-Pong Politics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2004 Hardball diplomacy and ping-pong politics: Cuban baseball, Chinese table tennis, and the diplomatic use of sport during the Cold War Matthew .J Noyes University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Noyes, Matthew J., "Hardball diplomacy and ping-pong politics: Cuban baseball, Chinese table tennis, and the diplomatic use of sport during the Cold War" (2004). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1841. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1841 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARDBALL DIPLOMACY AND PING-PONG POLITICS: CUBAN BASEBALL, CHINESE TABLE TENNIS, AND THE DIPLOMATIC USE OF SPORT DURING THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by Matthew J. Noyes Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2004 Department of History © Copyright by Matthew J. Noyes 2004 All Rights Reserved HARDBALL DIPLOMACY AND PING-PONG POLITICS: CUBAN BASEBALL, CHINESE TABLE TENNIS AND THE DIPLOMATIC USE OF SPORT DURING THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by Matthew J. Noyes Approved as to style and content by Ronald Story, Chair Jane TVl. Rausch, Member Laura Lovett, Member David Glassberg, Chair Department of History DEDICATION To my parents, never say thank you enough for all you have done for ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a deep debt of gratitude to a number of people without whom this thesis would never have been completed. -

Aa006263.Pdf (3.495Mb)

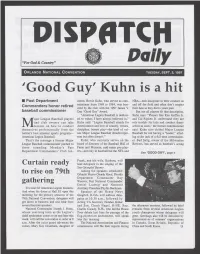

DISPATCH Orlando National Convention TUESDAY, SEPT. 2, 1997 'Good Guy' Kuhn is a hit ■ Past Department cheon. Bowie Kuhn, who served as com¬ NBA—lack discipline in their conduct on Commanders honor retired missioner from 1969 to 1984, was hon¬ and off the field and often don’t respect ored by the club with the 1997 James V. their fans as they did in years past. baseball commissioner Day “Good Guy” Award. But not all players fit that description, “American Legion Baseball is dedicat¬ Kuhn says. “Players like Ken Griffey Jr. ajor League Baseball players ed to values I have always believed in,” and Cal Ripken Jr. understand they are M Kuhn said. “Legion Baseball stands for and club owners can take role models for kids and conduct them¬ lessons on how to conduct Americanism and love of country, virtues, selves as such,” the former commissioner themselves professionally from the discipline, honest play—the kind of val¬ said. Kuhn also chided Major League nation’s best amateur sports program— ues Major League Baseball should repre¬ Baseball for not having a “leader,” allud¬ American Legion Baseball. sent but often doesn’t.” ing to the lack of a full-time commission¬ That’s the message a former Major Kuhn, who currently serves on the er. Bud Selig, owner of the Milwaukee League Baseball commissioner pitched to board of directors of the Baseball Hall of Brewers, has served as baseball’s acting those attending Monday’s Past Fame and Museum, said many pro play¬ Department Commanders’ Club lun¬ ers—not only in baseball but the NFL and See ‘GOOD GUY’, page 4 Frank, and his wife, Barbara, will Curtain ready lead delegates in the singing of the Star-Spangled Banner. -

And the Dodgers the Changing Face of America

Doug McDermott: The Changing Face He Bought the Farm … Is There an Miracles on Finishing the Journey of America and the Dodgers App for That? 24th Street Fall/Winter 2013 New Season, New Look The Creighton men’s basketball team tipped off the 2013-14 season Nov. 8 with a 107-61 win over Alcorn State in front of a record season-opening crowd of 17,740 and with a new center-court logo at the CenturyLink Center Omaha, part of a revamped athletic brand for Creighton. For the latest alumni events around CU athletics, visit the new Fan Central site (alumni.creighton.edu/fan-central). Photo by Jim Fackler University Magazine Message from the University President Volume 29, Issue 3 Publisher: Creighton University; Timothy R. Lannon, S.J., President. Creighton University The Momentum Grows Magazine staff: Carol Ash, Associate Vice Amid the changing higher education President for Marketing and Communications; Kim Barnes Manning, Assistant Vice President landscape, one thing is certain — the future for Marketing and Communications; Rick Davis, will not be like the past. Forward-thinking Director of Communications; Sheila Swanson, universities have momentum — they don’t stand Editor; Cindy Murphy McMahon, Writer; still. As you’ll read in this issue of Creighton Rosanne Bachman, Writer; Robyn Eden, Writer. University Magazine, our students, faculty, alumni Creighton University Magazine is published in the and donors are moving forward, building upon spring, summer and fall/winter by Creighton what’s good to make it great. University, 2500 California Plaza, Omaha, NE It has been a remarkable year at Creighton. 68178-0001. -

"The Boys in the Field" Traces History

8 THE CAROLINA TIMES SAT . AUGUST 16. 1980 "The Boys In The Field" Traces History Of Blacks In Baseball Sox Jim Rice 1980 marks the 35th an- Red outfielder of the that talks about being the only niversary year American black on the Jackie. Robinson signed a player contract with the Brooklyn team's roster. Pitchej Dodgers. This led to his Ferguson Jenkins gives some, into of becoming the first black man insight the problems a black in the to on a league being pitcher play major discuss baseball team. UNC-T- V major leagues. They 1 recruitment through scouting commemorates ttys occasion n 1 on Wednesday, 20 at systems .and advancement August the minor 8:00 with The Boys In through leagues. p.m. Whether race is or should The Field, a sixty-minu- te be a factor in these areas is sports special that traces the also discussed. When history of outstanding black Dodger Otero is ballplayers and examines the scout Regie ques- current status of blacks in tioned as to whether the ma- is professional baseball. jor league scouting system deficient in its of Taped at spr- recruiting he "As ing, training in Florida and at blacks, answers, long as can minor league ballparks in you play ball, we're interested. We all over. If North Carolina, this pro- go had a Chinese gram presents the views of they school, to be current and former players we're going there." Slim for and of management. Host job prospects retire Audrey Kates and writer black players after they Pama Mitchell interview from the game has become issue Reggie Jackson, Hank an of major concern. -

The NFL Makes It Rain: Through Strict Enforcement of Its Conduct

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 | Issue 3 Article 4 2008 The NFL akM es It Rain: Through Strict Enforcement of Its Conduct Policy, the NFL Protects Its Integrity, Wealth and Popularity Robert Ambrose Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Ambrose, Robert (2008) "The NFL akM es It Rain: Through Strict Enforcement of Its Conduct Policy, the NFL Protects Its Integrity, Wealth and Popularity," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 3, Article 4. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Ambrose: The NFL Makes It Rain: Through Strict Enforcement of Its Conduct 3. AMBROSE - ADC 4/23/2008 1:20:23 PM NOTE: THE NFL MAKES IT RAIN: THROUGH STRICT ENFORCEMENT OF ITS CONDUCT POLICY, THE NFL PROTECTS ITS INTEGRITY, WEALTH, AND POPULARITY † Robert Ambrose I. OPENING KICKOFF - INTRODUCTION ................................... 1070 II. FIRST DOWN – HANDLING MISCHIEF IN THE NFL ............... 1073 A. Disciplinary Action ......................................................... 1073 B. NFL’s Conduct Policy...................................................... 1073 1. Categorizing Misconduct............................................1074 -

From the Land of Bondage: the Greening of Major League Baseball Players and the Major League Baseball Players Association

Catholic University Law Review Volume 41 Issue 1 Fall 1991 Article 8 1991 From the Land of Bondage: The Greening of Major League Baseball Players and the Major League Baseball Players Association Michael J. Cozzillio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Michael J. Cozzillio, From the Land of Bondage: The Greening of Major League Baseball Players and the Major League Baseball Players Association, 41 Cath. U. L. Rev. 117 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol41/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAY/BOOK REVIEW From the Land of Bondage:* The Greening of Major League Baseball Players and The Major League Baseball Players Association Michael J. Cozzillio ** Marvin Miller's book, A Whole Different Ballgame: The Sport and Busi- ness of Baseball, is a breezy, informative and certainly controversial chroni- cle of the evolution of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA or Players Association) from an amoebic, ill-defined amalgam of players to a fully-developed specimen of trade unionism in professional sports.' Readers who seek to be entertained will find the sports anecdotes and inside information replete with proverbial page-turning excitement and energy. Those who seek to be educated in many of the legal nuances and practical ramifications of collective bargaining, antitrust regulation, individ- ual contract negotiation, and varieties of arbitration in the world of Major League Baseball will find Miller's book illuminating. -

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball

AUTOGRAPH RELIC AUTOGRAPH PATCH CARDS Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® Adrian Beltre Los Angeles Dodgers® Adrian Beltre Boston Red Sox® Albert Pujols Angels® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® Alex Rodriguez Seattle Mariners™ Alex Rodriguez Texas Rangers® Andrew Benintendi Boston Red Sox® Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ Brendan Rodgers Colorado Rockies™ Rookie Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie CC Sabathia New York Yankees® Charlie Blackmon Colorado Rockies™ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie Chris Sale Boston Red Sox® Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® Derek Jeter New York Yankees® Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ Rookie Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® Fred McGriff Atlanta Braves™ Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ George Springer Houston Astros® Gerrit Cole Houston Astros® Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ Ivan Rodriguez Texas Rangers® Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® Jacob deGrom New York Mets® Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® Jim Thome Philadelphia Phillies® Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ Jose Altuve Houston Astros® Jose Ramirez Cleveland Indians® Juan Soto Washington Nationals® Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ Ken Griffey Jr. Cincinnati Reds® Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® Kyle Schwarber Chicago Cubs® Luis Severino New York Yankees® Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® Mark McGwire Oakland Athletics™ Mark McGwire St. -

Baseball Justice

Peter Dreier: Baseball Justice LikeThe Huffington Post 224K February 15, 2011 This is the print preview: Back to normal view » Peter Dreier Posted: July 24, 2010 06:03 PM Baseball Justice As baseball inducts slugger Andre Dawson, umpire Doug Harvey and manager Whitey Herzog into its Hall of Fame at ceremonies in Cooperstown, New York on Sunday, the glaring absence of Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the players' union, and Curt Flood, the baseball pioneer who challenged the sport's feudal system, reminds us of the narrow parochialism and conservatism of baseball's current establishment. All histories of baseball point with pride to its role in helping to dismantle America's racial caste system when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. In recent years, however, Major League Baseball (MLB) has hardly distinguished itself as a paragon of American virtue or a pioneer for social justice or moral clarity. Its corporate mentality, its failure to deal with widespread drug use, and its decline in popularity among America's youth (more of whom now play soccer than Little League file:///H|/Dreier/PDFs%20of%20Dreier's%20Articles/Baseball%20Justice.html (1 of 22)2/15/2011 11:35:41 AM Peter Dreier: Baseball Justice baseball), don't reflect well on what its pooh- bahs still call the "national pastime." Here are five things that baseball could do to redeem itself to reflect the best of America's liberty-and-justice-for-all values. 1. Elect Marvin Miller to the Hall of Fame The man who freed ballplayers from indentured servitude has been kept out of the Hall of Fame as a result of a coup engineered by the conservative cabal that controls Major League Baseball.