The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E933 HON

June 27, 2018 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E933 PERSONAL EXPLANATION and would invest billions of dollars in Presi- Famers like Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, dent Trump’s unnecessary border wall and Ernie Banks, Willard Brown, and Buck O’Neil. HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ military technology along the border. The Kansas City Blues and Monarchs lead Kansas City in its original baseball fandom, OF ILLINOIS Overall, the bill would simply dismantle fami- lies, detain innocent immigrants and children eventually resulting in the establishment of the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for prolonged, indefinite amounts of time, and city’s first stadium in 1923. Known initially as Wednesday, June 27, 2018 closes our border and walls to people around Muehlebach Field, the stadium is rooted adja- Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- the world who are ready to contribute to the cent to the Historic 18th and Vine Jazz Dis- avoidably absent in the House chamber for American dream. trict. This stadium would change hands sev- Roll Call votes 291, 292, 293, 294 and 295 on This is not what America is or has ever eral times; however, in the early 1950’s, a Tuesday, June 26, 2018. Had I been present, been. Our diverse nation was built by immi- wealthy real estate developer purchased the I would have voted Nay on Roll Call votes grants coming here to build for themselves stadium, as well as the Philadelphia Athletics, 291, 292, 294 and 295. I would have voted and their families, along with other commu- with the goal of bringing a major league team Yea on Roll Call vote 293. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Raised Their Own Solutions

_ .-.-'., ~-'~ • u:: • -,... • ,:~ i '~:' :", ' i' .V£cCdi:£a, ~ ;C. ' ..... ": i : New ,- . ,,.,' ts ...... Herala ~ta~! wn~r ~. - . -. - " : ,. TERRACE-- Restsarant owners and'numag Ts.,are :, . • .....- '.'. 4- .'=~',~v",~, ='q$. more ='1~',roblen= . ~Wi,h~.= the* neWmeal:: ... tax • rules~. than• ,): ,', ~ ~o~x/~'" " *their customers.-All the cUstomers have tO d0Is pay.::The ? :--, ' ~: "~= t:., - .r~tahrate~_rs. ba~e't o figure it out. ::- / .' ./" ~-::,; ' ::.'-.': • .( ...~..~. .!:,) :"/..}:: .Not.:aH nieail~fl_e[s~e ~ndl~ng~":p~ib!edi th,: .mime*.' :.. -(• • ! ,• /--'.~:: : !: •'. ,; • /.The newseven ~1. :cent tax:0nmeals!con~umed 0h. ,the ' •. iL , ' - • " ,-!.i}/i,/~::~ ':(i,~.,,,i '.~',5~ .' i premisesor'arestaurant;weresup~togbintoeffettat. • . ....... -., • . .. mi~igbtWhenThu~diiy,jniy?boeameFriday,julye. ..... r ~ / .-, I . , = - ..... ".; .,o. • . ! , Monday., July 11, 1983 .j -, • "~ Me ]~2 That m ,=elf became a pr0blem..Some managers hadn t, • : 25 cents .~ ,;'~i~.Estab'ii lvo8 _. Volome'77 ........ , .... i " ' ' t .... --.. " been able:ta understand-whatthenew~rules'were:bytho .... ... time, so they basically ignored 1~em until they could gather more information.... " " "" For those restaurants that were open that night untilpast ~ "midnight and tried to put the new tax into effect it was . Abortion something of a nightmare. Do you charge the seven per cent on meals served before midnight but not paid for until after? Or do you only charge the tax on meals that were money served after the deadline? If ameal was ordered at 1!:59 p.m. that became a whble other problem..The matter was so confusing that individualmanagers were coming up with raised their own solutions. Which means depending upon' the managers, customers who 'ordered the same, meal In t TORONTO CP " -- separate establishments were i~aying different prices when Supporters of Dr. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Support for Begins to Un

The weather ■it.'-;. ITT ' ' ’ Sunny today with high near 70. In- creaiing cioudineu tonight with low SO SO. Tueiday variable cloudiness with CIWU chance ot a few showers. High in 70s. Cbahce of rain 20% tonight, 30% Tuesday. National weather forecast map on Page 7-B. FRia>:i nrr6tN.< Support for begins to un WASHINGTON (UPI) - Decision facing the committee and explainiaf a i week in the Bert Lance controversy his dealings. began t^ a y with political support for "I know that Mr. Lance hat not the White House budget director un made any such decision,” Clifford raveling as he prepared for his day in told the Washington Star. "He fecit the witness chair. he has committed no illegality and, Supporters of the former Atlanta in his opinion, no impropriety ... I banker asked only that Lance be believe it is absolutely incorrect that given a chance to answer the charges in public. 'The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee scheduled fresh Balloonil testimony from a series of govern ment officials, culminating ’Thursday with Lance’s own appearance. Carter plans a news conference Wednesday, the day before Lance call for testifies. Questions of Comptroller of the REYKJAVIK, Iceland (UPI) - Currency John Heimann were likely Two Albuquerque, N.M., men trying Army-Navy Club has family picnic to center on a newly released Inter to become the first to fly the Atlantic in a balloon, ran low on fuel today Members and families of the Army-Navy Club and Auxiliary enjoy picnicking and play nal Revenue Service report detailing efforts by Lance to conceal financial after more than 60 hours aloft and Sunday at the group’s 18th annual family picnic, at Globe Hollow. -

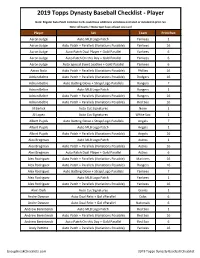

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

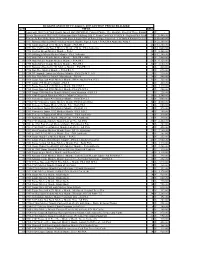

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

GAME #68/HOME #36 RHP JAKE ARRIETA (6-4, 4.68 ERA) Vs

CHICAGO CUBS (33-33) vs. PITTSBURGH PIRATES (30-37) JUNE 17, 2017 at PNC Park, Pittsburgh, PA --- GAME #68/HOME #36 RHP JAKE ARRIETA (6-4, 4.68 ERA) vs. RHP IVAN NOVA (6-4, 2.83 ERA) THE PIRATES...have lost back-to-back games after winning a season-high four straight between 6/10-13...Have gone 16-15 in their last 31 games, dating back to 5/13...Have scored a season-high 12 runs four times; the last time coming on 6/2 at New York (NL)...Had a 33-34 record after 67 games last season (33-35 after 68). SATURDAYS IN THE PARK: The Pirates have gone 8-2 on Saturdays this season, losing only to the two teams from New York; BUCS WHEN... the Yankees at PNC Park on 4/22 and the Mets at Citi Field on 6/3...The Bucs have posted the third-highest batting average (.290) among all Major League teams on Saturdays this year, trailing only Colorado (.299) and Oakland (.291). Last five games ................ 3-2 IVAN THE GREAT: Ivan Nova has pitched at least 6.0 innings in each of his first 13 starts this season; the first Pittsburgh Last ten games .................4-6 pitcher to do so since Eddie Solomon, who pitched 6.0 innings or more in all 17 starts in 1981...Nova pitched 6.0 scoreless innings in his last start and has been charged with two earned runs or less in six of his 13 assignments this year...He enters Leading after 6 .................21-5 today’s action ranked first in the National League with two complete games, sixth in ERA (2.83) and sixth in innings pitched (89.0). -

Loretta B. Brown Estate STATE of MICHIGAN COURT of APPEALS

Every month I summarize the most important probate cases in Michigan. Now I publish my summaries as a service to colleagues and friends. I hope you find these summaries useful and I am always interested in hearing thoughts and opinions on these cases. PROBATE LAW CASE SUMMARY BY: Alan A. May Alan May is a shareholder who is sought after for his experience in guardianships, conservatorships, trusts, wills, forensic probate issues and probate. He has written, published and lectured extensively on these topics. He was selected for inclusion in the 2007 through 2011 issues of Michigan Super Lawyers magazine featuring the top 5% of attorneys in Michigan and is listed in the 2011 and 2012 compilations of The Best Lawyers in America. He has been called by courts as an expert witness on issues of fees and by both plaintiffs and defendants as an expert witness in the area of probate and trust law. He is listed by Martindale-Hubbell in the area of Probate Law among its Preeminent Lawyers. He is a member of the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR). For those interested in viewing previous Probate Law Case Summaries, click on the link below. http://www.kempklein.com/probate-summaries.php DT: December 19, 2011 RE: Loretta B. Brown Estate STATE OF MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS BASEBALL STATS: “MEMORIES OF A PITTSBURGH FAN” Guest Editorial by: Barbara Andruccioli of Kemp Klein Law Firm Being born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and genetically predisposed to being a sports fan, I have some wonderful sports memories the most memorable occurring during the 1970’s. -

Green Energy Boosts MLB Exec Lewis In

Green energy boosts MLB exec Lewis in her ’87 start with the Cubs By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Tuesday, September 10th, 2013 Wendy Lewis knew she was entering a brave new world when she walked into Dallas Green’s Wrigley Field office in the early summer of 1987 to get his blessing as the team’s first manager of human re- sources. Lewis had the backing of par- ent Tribune Co., where she had worked for the Chicago Tribune. But she didn’t know quite what to expect from vol- uble Cubs president-general manager Green, whose 50,000-watt booming voice Wendy Lewis (left) with granddaughter Samya Lewis-Kemp after could announce his presence the Civil Rights roundtable discussion at the Chicago Cultural before his expansive 6-foot-5 Center. frame actually filled the room. Here was a woman – a minority one, at that – entering the boys club of a baseball team. And Green, who had shaken the Cubs to the core in dragging them out of the moss- backed Wrigley family ownership, reeked of testosterone with a triple dose. “One of the last organization changes (Tribune Co. mandated for the team) is they want- ed the Cubs to develop a human resources department,” said Lewis, now senior vice president of diversity and strategic alliances for Major League Baseball. “They didn’t have one, nor did any other team. For Dallas, it was an interesting inter- view because it was a lot of what are you going to do? What was interesting about that interview with Dallas was not only (his asking) who are you, but what in the world can you do for this organization? “From his perspective, this sort of professional, an HR pro, didn’t make sense at the www.ChicagoBaseballMuseum.org [email protected] time. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

1981 Transactions

1981 Season Transactions 1. Dashwood releases Bobby Bonds, Barry Foote, Bob Molinaro, Len Randle and Bill Robinson (August 27) 2. Brooklyn releases Larry Cox, Fred Stanley and Mike Vail (August 27) 3. Margaritaville releases Jose Morales, Enrique Romo, Greg Pryor, Junior Kennedy, Ron Pruitt, Garry Hancock, Brian Asselstine. Jerry White and Tim Corcoran (August 27) 4. Milwaukee releases Jim Anderson, Mitchell Page, Gordie Pladson, Bill Travers and Mike Willis (August 27) 5. Manchester releases Bobby Brown, Rafael Landestoy, Mike Sadek, Warren Brusstar and Dave Ford (August 27) 6. Gettysburg releases Marc Hill, Jeff Newman, Ken Macha, Joe Pettini, Lamar Johnson, Mark Bomback, Jesse Jefferson, Bob Sykes, Jim Kaat, Bob Owchinko, Dick Drago and Dale Murray (August 27) 7. Lincoln releases Dave Chalk, Ted Cox, Paul Mirabella, Freddie Patek, Don Robinson and Dan Whitmer (August 28) 8. Berkeley releases Willie Montanez, Dave A. Roberts, Dave Rosello, Joe Rudi. Jim Spencer and Sandy Wihtol (UNC) (August 28) 9. Minnesota releases Larry Harlow, Darrell Jackson and Joe Strain (August 28) 10. Columbus releases Glenn Adams, Larry Biittner, Mike Cubbage, Nino Espinosa, Ross Grimsley (UNC), Dave Heaverlo, Mike Parrott, Aurelio Rodriguez, Willie Stargell, Jim Wohlford and Rich Wortham (UNC) (August 28) 11. Louisville releases Dave Edwards, John Flinn (UNC), Mike Jorgensen, Rick Matula, Bill Nahorodny and Dave W. Roberts (August 28) 12. El Paso releases Gary Alexander, Sal Bando, Kevin Bell (UNC), Ed Glynn and Del Unser. (August 28) 13. New Hampshire releases Kurt Bevacqua, Steve Crawford, Dave Frost, Dennis Kinney, Ken Kravec, Dan Larson, Randy Niemann (UNC) and Reid Nichols (August 28) 14.