Designated Hitters and Subesquent Team Scoring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test

The “Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test One of the many beauties of baseball, affectionately known as “America’s pastime,” is the ability for people to come to the stadium and become ingrained in the action and get the chance to interact with their heroes. Going to a baseball game, as opposed to going to most other sporting events, truly gives a fan the opportunity to take part in the action. However, this can come at a steep price as foul balls enter the stands at alarming speeds and occasionally strike spectators. According to a recent study, approximately 1,750 people get hurt each year by batted 1 balls at Major League Baseball (MLB) games, which adds up to twice every three games. The 2015 MLB season featured many serious incidents that shed light on the issue of 2 spectator protection. This has led to heated debates among the media, fans, and even players and 3 managers as to what should be done to combat this issue. Currently, there is a pending class action lawsuit against Major League Baseball (“MLB”). The lawsuit claims that MLB has not 1 David Glovin, Baseball Caught Looking as Fouls Injure 1,750 Fans a Year, BLOOMBERG BUSINESS (Sept. 9, 2014, 4:05 PM), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/20140909/baseballcaughtlookingasfoulsinjure1750fansayear. 2 On June 5, a woman attending a Boston Red Sox game was struck in the head by a broken bat that flew into the seats along the third baseline. See Woman hurt by bat at Red Sox game released from hospital, NEW YORK POST (June 12, 2015, 9:32 PM), http://nypost.com/2015/06/12/womanhurtbybatatredsoxgamereleasedfromhospital/. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds Gavel.) Good Afternoon and Welcome to the National Press Club. My Name Is Donna Leinwand. I'm a Repor

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JEFF IDELSON SUBJECT: JEFF IDELSON, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME, IS SCHEDULED TO SPEAK AT A NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON MAY 11. HALL OF FAME THIRD BASEMAN BROOKS ROBINSON WILL BE A SPECIAL GUEST. MODERATOR: DONNA LEINWAND, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MAY 11, 2009 (C) COPYRIGHT 2009, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Donna Leinwand. I’m a reporter at USA Today and I’m president of the National Press Club. We’re the world’s leading professional organization for journalists and are committed to a future of journalism by providing informative programming, journalism education and fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. On behalf of our 3,500 members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speaker and our guests in the audience today. I’d also like to welcome those of you who are watching us on C-Span. We’re looking forward to today’s speech, and afterwards, I’ll ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

BSITH Los Angeles Angels Offical Rules.Docx

Best Seats in the House at Angel Stadium Sweepstakes The following terms, conditions and rules ("Official Rules") explain and govern the "Best Seats in the House at Angel Stadium Sweepstakes" ("Sweepstakes") as presented and sponsored by Jerome’s Furniture Warehouse, 16960 Mesamint St., CA 92127 (“Jerome’s” or “Contest Administrator”), with permission from Angels Baseball LP (“ABLP”) regarding Prizes being offered. NO PURCHASE OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN THIS SWEEPSTAKES. A PURCHASE WILL NOT IMPROVE YOUR CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED OR RESTRICTED BY LAW. SWEEPSTAKES PERIOD: The Sweepstakes begins on March 23, 2021, and ends on September 2, 2021 (“Sweepstakes Period”). The Sweepstakes Period will consist of (12) “Entry Periods" as set forth in the chart below: Entry Period Home Game Start Date End Date Designated Drawing Date Date (on or about) 1 4/1/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/2/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/3/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/4/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/5/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/6/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 2 4/16/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/17/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/18/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/19/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/20/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/21/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 3 5/3/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/4/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/5/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/6/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/7/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 -

Chicago Cubs (84-66) Vs. Tampa Bay Rays (73-78) September 20, 2017 … Tropicana Field … Game No

Chicago Cubs (84-66) vs. Tampa Bay Rays (73-78) September 20, 2017 … Tropicana Field … Game No. 151 … Road Game No. 73 LHP Jon Lester (11-7, 4.30) vs. LHP Blake Snell (3-6, 4.25) ONE-HIT WONDER-FUL: The Chicago Cubs, winners of a season-high seven-straight CUBS VS. RAYS games and now a season-high 18-games over .500, tonight play the final game of a CUBS RECORD The Cubs and Rays play four games this brief two-game set against the Tampa Bay Rays … Chicago last night won the series 2017 Overall: .......................................... 84-66 season, spanning two series … the teams split opener, 2-1, as Mike Montgomery allowed one hit (a Brad Miller solo homer in the At Wrigley Field: .................................. 46-32 two games at Wrigley Field, July 4-5 … this is sixth) and Pedro Strop, Carl Edwards Jr. and Wade Davis combined for three hitless On the Road: ........................................ 38-34 the first time Cubs manager Joe Maddon has innings to give Chicago its first combined one-hitter since Sept. 12 of last season at April: ................................................. 13-11 been to Tropicana Field since joining the Cubs the Cardinals in a 4-1 win. May:.................................................. 12-16 in 2015 … he managed the Rays from 2006- © In that game last season, Chicago’s lone hit allowed was also a home run as Kyle June: ................................................. 15-13 14, guiding them to the A.L. Pennant in 2008. Hendricks had his no-hit bid broken up by a Jeremy Hazelbaker homer to start July ...................................................... 16-8 the ninth … Aroldis Chapman got the final three outs. -

Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum Wayoakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 PR on Twitter @Asmedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS

O AKLAND A THLETICS Game Information Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum WayOakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900www.athletics.comA’s PR on Twitter @AsMedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (13-19-1) SATURDAY, APRIL 2, 2016 – OAKLAND ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM – 1:05 P.M. PST CSNCA – A’S RADIO NETWORK (95.7 FM THE GAME) ABOUT THE A’S: Have lost five straight and eight of the last nine games… for the lead in runs (11)…has appeared in 14 games in left field and three this is the A’s longest Spring Training losing streak since dropping the final in right field…Jed Lowrie is 7-for-18 (.389) over his last seven games six games of 2011…are 11-17-3, which is the third worst record among and is batting .395 overall…nine of his last 12 hits are for extra bases Cactus League teams (San Diego, 10-20-2; Chicago-NL, 11-18-2)…will (seven doubles, one triple, one home run)…leads the A’s and is tied for finish with a losing record for the first time since 2011 when they went fifth in the CL in doubles (7)…is tied for the team lead in slugging (.674)… 12-21-1…the A’s have committed 44 errors, which is seven more than any has appeared in 15 games at second base and two at shortstop…Bruce other team (37, Chicago-NL)…the errors are the most by an A’s team dur- Maxwell (NR) is 2-for-11 (.182) with a home run and two RBI in 10 games ing the spring since the 2002 club also had 44…the A’s pitching staff is tied since returning from playing for Germany in the World Baseball Classic with Boston for the most walks (123)…have matched -

Time to Drop the Infield Fly Rule and End a Common Law Anomaly

A STEP ASIDE TIME TO DROP THE INFIELD FLY RULE AND END A COMMON LAW ANOMALY ANDREW J. GUILFORD & JOEL MALLORD† I1 begin2 with a hypothetical.3 It’s4 the seventh game of the World Series at Wrigley Field, Mariners vs. Cubs.5 The Mariners lead one to zero in the bottom of the ninth, but the Cubs are threatening with no outs and the bases loaded. From the hopeful Chicago crowd there rises a lusty yell,6 for the team’s star batter is advancing to the bat. The pitcher throws a nasty † Andrew J. Guilford is a United States District Judge. Joel Mallord is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a law clerk to Judge Guilford. Both are Dodgers fans. The authors thank their friends and colleagues who provided valuable feedback on this piece, as well as the editors of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review for their diligent work in editing it. 1 “I is for Me, Not a hard-hitting man, But an outstanding all-time Incurable fan.” OGDEN NASH, Line-Up for Yesterday: An ABC of Baseball Immortals, reprinted in VERSUS 67, 68 (1949). Here, actually, we. See supra note †. 2 Baseball games begin with a ceremonial first pitch, often resulting in embarrassment for the honored guest. See, e.g., Andy Nesbitt, UPDATE: 50 Cent Fires back at Ridicule over His “Worst” Pitch, FOX SPORTS, http://www.foxsports.com/buzzer/story/50-cent-worst-first-pitch-new-york- mets-game-052714 [http://perma.cc/F6M3-88TY] (showing 50 Cent’s wildly inaccurate pitch and his response on Instagram, “I’m a hustler not a damn ball player. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

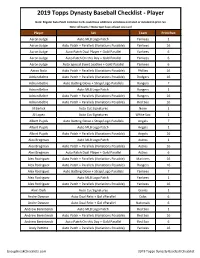

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

On the Field at Kauffman Stadium Before the May 13Th Game Between

On the field at Kauffman Stadium before the May 13th game between the Kansas City Royals and Colorado Rockies I was looking for Rene Lachemann to tell him that one of his former teammates wanted to see him. But Rene was not around, so I began asking different Rockies players and staff if they had seen Mr. Lachemann. All of them responded with the same reply, “You will hear him before you see him.” Soon it was discovered what they meant as the bench coach of the Rockies made his way up from under the stadium where he had been working with one of the catchers, and his booming voice could be heard. This voice has been heard by many major league and minor league players for many years as Rene Lachemann has managed and coached and trained these players in the finer points of the game. Rene was born in Los Angeles California and is the youngest of three brothers to have long careers in professional baseball. Rene served as a batboy for the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1959 to 1962, went to the University of California and was signed by the Kansas City Athletics in 1964 as a catcher. He played for the KC A’s in 1965 and 1966 and moved with the team to Oakland appearing in games in 1968. He began managing in the Oakland minor leagues in 1973 spending 5 seasons in the A’s system before going to the Seattle Mariners organization. He took his first major league managers job in 1981 with the Mariners succeeding Maury Wills, and led the M’s from 1981-1983.