Hardball Diplomacy and Ping-Pong Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYTHS of the ENEMY: CASTRO, CUBA and HERBERT L. MATTHEWS of the NEW YORK TIMES Anthony Depalma Working Paper #313

MYTHS OF THE ENEMY: CASTRO, CUBA AND HERBERT L. MATTHEWS OF THE NEW YORK TIMES Anthony DePalma Working Paper #313 - July 2004 Anthony DePalma was the first foreign correspondent of The New York Times to serve as bureau chief in both Mexico and Canada. His book about North America, Here: A Biography of the New American Continent, was published in the United States and Canada in 2001. During his 17-year tenure with The Times, he has held positions in the Metropolitan, National, Foreign and Business sections of the newspaper, and from 2000 to 2002, he was the first Times international business correspondent to cover North and South America. As a Kellogg fellow in Fall ’03, he conducted research for a book on Fidel Castro, Herbert Matthews, and the impact of media on US foreign policy. The book will be published by Public Affairs in 2005 or early 2006. ABSTRACT Fidel Castro was given up for dead, and his would-be revolution written off, in the months after his disastrous invasion of the Cuban coast in late 1956. Then a New York Times editorial writer named Herbert L. Matthews published one of the great scoops of the 20th century, reporting that not only was Castro alive, but that he was backed by a large and powerful army that was waging a successful guerrilla war against dictator Fulgencio Batista. Matthews, clearly taken by the young rebel’s charms, and sympathetic to his cause, presented a skewed picture. He called Castro a defender of the Cuban constitution, a lover of democracy, and a friend of the American people: the truth as he saw it. -

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

59Th Primetime Emmys Winners Revealed Sopranos, 30 Rock Take Top Series Honors

59th Primetime Emmys Winners Revealed Sopranos, 30 Rock Take Top Series Honors September 16, 2007—A notorious crime family, a fictional sketch-comedy show, an iconic singer and a female British detective were among the big winners at the 59th Primetime Emmy Awards, which took place at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles and was telecast on the Fox network. Host for the ceremony was American Idol host Ryan Seacrest. Other highlights included a 30th anniversary tribute to a groundbreaking miniseries and a moving musical send-off to one of the most celebrated series in television history. Among the twenty-nine categories honored, NBC topped the list with seven wins. ABC and HBO followed closely with six winged statuettes each. Combined with their awards at last Saturday’s Creative Arts Emmys, the three networks led for the year as well: HBO earned twenty-one, NBC nineteen and ABC ten. CBS, which won one award on the night, also earned a total of ten between the two shows. The Sopranos, HBO’s acclaimed production about the travails of a New Jersey Mob boss and his intertwined biological and criminal families, took the prize for Outstanding Drama Series, and 30 Rock, NBC’s look at the backstage activity at a late-night sketch- comedy show, was named Outstanding Comedy Series. The Sopranos, the NBC special Tony Bennett: An American Classic, the AMC miniseries Broken Trail and the PBS Masterpiece Theatre production Prime Suspect: The Final Act led the recipients of multiple awards with three each. The ABC comedy Ugly Betty took two, including Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series for its star, America Ferrera. -

A Strong Case for a New START a National Security Briefing Memo

A Strong Case for a New START A National Security Briefing Memo Max Bergmann and Samuel Charap April 6, 2010 What is New START and why do we need it? New START, the agreement between the United States and Russia on a successor to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, is a historic achievement that will increase the United States’ safety and security. It will help us move beyond the outdated strategic approaches of the Cold War and reduce the threat of nuclear war, and marks a significant step in advancing President Barack Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons. It also shows that his policy of constructive engagement with Russia is working. New START strengthens and modernizes the original START Treaty that President Ronald Reagan initiated in 1982 and George H.W. Bush signed in 1991. That agreement significantly reduced the number of nuclear weapons and launchers, but it also embodied Reagan’s favorite Russian proverb “trust but verify” by establishing an extensive verifica- tion and monitoring system to ensure compliance. This system helped build trust and mutual confidence that decreased the unimaginable consequences of а conflict between the world’s only nuclear superpowers. Yet President George W. Bush’s reckless policies left this cornerstone of nuclear stability’s fate in doubt. Bush effectively cut off relations between the United States and Russia on nuclear issues by unilaterally pulling out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and refusing to engage in negotiations on a successor to START even though it was set to expire less than a year after he left office. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Images and Dilemmas in International Relations

Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Images and Dilemmas in International Relations Dustin Tingley [email protected] Department of Government, Harvard University Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Introduction Three images of IR I Man I State I System Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests -

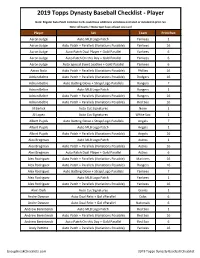

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

"Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2000 "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O. Regalado California State University, Stanislaus Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Regalado, Samuel O. (2000) ""Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition SAMUEL 0. REGALADO ° INTRODUCTION "Bonuses? Big money promises? Uh-uh. Cambria's carrot was the fame and glory that would come from playing bisbol in the big leagues," wrote Ray Fitzgerald, reflecting on Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria's tactics in recruiting Latino baseball talent from the mid-1930s through the 1950s.' Cambria was the first of many scouts who searched Latin America for inexpensive recruits for their respective ball clubs. -

Reconciliation in the Aftermath of Political Violence

Unchopping a Tree In The Series Politics, History, and Social Change, edited by John C. Torpey Also in this series: Rebecca Jean Emigh, The Undevelopment of Capitalism: Sectors and Markets in Fifteenth- Century Tuscany Aristide R. Zolberg, How Many Exceptionalisms? Explorations in Comparative Macroanalysis Thomas Brudholm, Resentment’s Virtue: Jean Améry and the Refusal to Forgive Patricia Hill Collins, From Black Power to Hip Hop: Racism, Nationalism, and Feminism Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider, translated by Assenka Oksiloff, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age Brian A. Weiner, Sins of the Parents: The Politics of National Apologies in the United States Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley, Seeking Mandela: Peacemaking Between Israelis and Palestinians Marc Garcelon, Revolutionary Passage: From Soviet to Post- Soviet Rus sia, 1985– 2000 Götz Aly and Karl Heinz Roth, translated by Assenka Oksiloff, The Nazi Census: Identifi cation and Control in the Third Reich Immanuel Wallerstein, The Uncertainties of Knowledge Michael R. Marrus, The Unwanted: Eu ro pe an Refugees from the First World War Through the Cold War ❖Unchopping a Tree Reconciliation in the Aftermath of Political Violence Ernesto Verdeja Temple University Press Philadelphia Temple University Press 1601 North Broad Street Philadelphia PA 19122 www .temple .edu/ tempress Copyright © 2009 Temple University All rights reserved Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48- 1992 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Verdeja, Ernesto. Unchopping a tree : reconciliation in the aftermath of po liti cal violence / Ernesto Verdeja. -

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

Cuban Baseball Players in America: Changing the Difficult Route to Chasing the Dream

CUBAN BASEBALL PLAYERS IN AMERICA: CHANGING THE DIFFICULT ROUTE TO CHASING THE DREAM Evan Brewster* Introduction .............................................................................. 215 I. Castro, United States-Cuba Relations, and The Game of Baseball on the Island ......................................................... 216 II. MLB’s Evolution Under Cuban and American Law Regarding Cuban Baseball Players .................................... 220 III. The Defection Black Market By Sea For Cuban Baseball Players .................................................................................. 226 IV. The Story of Yasiel Puig .................................................... 229 V. The American Government’s and Major League Baseball’s Contemporary Response to Cuban Defection ..................... 236 VI. How to Change the Policies Surrounding Cuban Defection to Major League Baseball .................................................... 239 Conclusion ................................................................................ 242 INTRODUCTION For a long time, the game of baseball tied Cuba and America together. However as relations between the countries deteriorated, so did the link baseball provided between the two countries. As Cuba’s economic and social policies became more restrictive, the best baseball players were scared away from the island nation to the allure of professional baseball in the United States, taking some dangerous and extremely complicated routes * Juris Doctor Candidate, 2017, University of Mississippi