Cuban Baseball Players in America: Changing the Difficult Route to Chasing the Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second AMENDED COMPLAINT Against YASIEL PUIG VALDES

CoastCORBACHO Guard crew DAUDINOT reflects on time v. PUIG with Yasi VALDESel Puig etduring al attempt to defe... http://sports.yahoo.com/news/coast-guard-crew-reflects-on-time-with-yas...Doc. 24 Att. 7 Home Mail News Sports Finance Weather Games Groups Answers Flickr More Sign In Mail Tue, Jul 2, 2013 9:24 AM EDT Jun 27, 2013; Los Angeles, CA, USA; Los Angeles Dodgers right fielder Yasiel Puig (66) reacts after the game against the Philadelphia Phillies at Dodger Stadium. The Dodgers defeated the Phillies 6-4.... more 1 / 17 USA TODAY Sports | Photo By Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports It was time for a boat chase, the sort they craved. Months idling on the open seas left those aboard the Vigilant, a United States Coast Guard cutter, thirsting for action, and in the middle of April 2012, here it was. Somewhere in the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti, a lookout on the top deck spotted a speedboat in the distance. "I’ve got a contact," he said, and for Chris Hoschak, the officer on deck, that meant one thing: Get a team ready. He summoned Colin Burr, who had just qualified to drive the Coast Guard's Over the Horizon-IV boats that hunt bogeys in open water space. Before boarding, Burr and four others mounted up: body armor, gun belts and a cache of guns in case it was drug smugglers, which everyone figured because go-fast boats tend to traffic product instead of humans. The chase didn't last long. Maybe five or 10 minutes. -

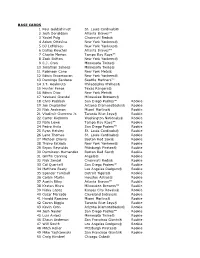

Checklist 19TCUB VERSION1.Xls

BASE CARDS 1 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 2 Josh Donaldson Atlanta Braves™ 3 Yasiel Puig Cincinnati Reds® 4 Adam Ottavino New York Yankees® 5 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees® 6 Dallas Keuchel Atlanta Braves™ 7 Charlie Morton Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Zack Britton New York Yankees® 9 C.J. Cron Minnesota Twins® 10 Jonathan Schoop Minnesota Twins® 11 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 12 Edwin Encarnacion New York Yankees® 13 Domingo Santana Seattle Mariners™ 14 J.T. Realmuto Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Hunter Pence Texas Rangers® 16 Edwin Diaz New York Mets® 17 Yasmani Grandal Milwaukee Brewers® 18 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Jon Duplantier Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 20 Nick Anderson Miami Marlins® Rookie 21 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 22 Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie 23 Nate Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 24 Pedro Avila San Diego Padres™ Rookie 25 Ryan Helsley St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 26 Lane Thomas St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 27 Michael Chavis Boston Red Sox® Rookie 28 Thairo Estrada New York Yankees® Rookie 29 Bryan Reynolds Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 30 Darwinzon Hernandez Boston Red Sox® Rookie 31 Griffin Canning Angels® Rookie 32 Nick Senzel Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 33 Cal Quantrill San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Matthew Beaty Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 35 Spencer Turnbull Detroit Tigers® Rookie 36 Corbin Martin Houston Astros® Rookie 37 Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 38 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 39 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® Rookie 40 Oscar Mercado Cleveland Indians® Rookie -

C:\Documents and Settings\Holy Cross\Desktop\Repec\Spe\HC Title Page (PM).Wpd

Working Paper Series, Paper No. 06-27 Revenue Sharing in Sports Leagues: The Effects on Talent Distribution and Competitive Balance Phillip Miller† November 2006 Abstract This paper uses a three-stage model of non-cooperative and cooperative bargaining in a free agent market to analyze the effect of revenue sharing on the decision of teams to sign a free agent. We argue that in all subgame perfect Nash equilibria, the team with the highest reservation price will get the player. We argue that revenue sharing will not alter the outcome of the game unless the proportion taken from high revenue teams is sufficiently high. We also argue that a revenue sharing system that rewards quality low-revenue teams can alter the outcome of the game while requiring a lower proportion to be taken from high revenue teams. We also argue that the revenue sharing systems can improve competitive balance by redistributing pivotal marginal players among teams. JEL Classification Codes: C7, J3, J4, L83 Keywords: competitive balance, revenue sharing, sports labor markets, free agency * I thank Dave Mandy, Peter Mueser, Ken Troske, Mike Podgursky, Jeff Owen, and two anonymous referees for valuable comments on earlier drafts. Their suggestions substantially improved the paper. Any remaining errors or omissions are my own. †Phillip A. Miller, Department of Economics, Morris Hall 150, Minnesota State University, Mankato, Mankato, MN 56001, E-mail: [email protected], Phone: 507-389- 5248. 1. Introduction Free agency has been cheered by players and agents but has been scorned by team owners. Player salaries under free agency have expanded to an extent that many fans believe small market teams now have difficulty in competing for playing talent and on the playing field, worsening the competitive balance between teams. -

The Effect of Major League Baseball on United States-Cuba Relations

THE EFFECT OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL ON UNITED STATES-CUBA RELATIONS Ryan M. Schur TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. THE HISTORY OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL’S IMPACT ON THE UNITED STATES-CUBA RELATIONS A. United States-Cuba Relations Pre-Embargo B. United States-Cuba Relations Post Embargo C. The Embargo’s Restrictions on the Freedom of Cuban Baseball Players III. AMATEUR DRAFT v. FREE AGENCY A. MLB Eligibility Rules B. Free Agency IV. IMPLICATIONS OF DEFECTION A. Dangers of Defection by Sea B. Humanitarian Violations V. FUTURE IMPLICATIONS OF BASEBALL ON UNITED STATES-CUBA RELATIONS A. Strides Toward Improvement B. Possible Solutions 1. Baseball Diplomacy Act 2. Worldwide Draft C. Cuban Participation in Major League Baseball Benefits Both the United States and Cuba VI. CONCLUSION 2 ABSTRACT Since the United States began its embargo of Cuba, Cuban-born men have defected from their homeland to pursue their dreams of freedom and playing Major League Baseball. Attempts at defection from Cuba pose significant risks to these players, ranging from death during the treacherous 90-mile journey from Cuba to the Florida coast, to their capture in route and repatriation back to Cuba to face harsh punishment from the Cuban Communist government. This paper examines the history of Major League Baseball’s impact on the United States-Cuba relations pre-embargo compared to the restrictions the embargo placed on Cuba after enactment and the effect the embargo had on Cuban men competing in the Major Leagues. It will examine how the Major League draft differs from the free agency system and the incentive free agency provides to Cuban men to defect. -

2017 Game Notes

2017 GAME NOTES American League East Champions 1985, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2015 American League Champions 1992, 1993 World Series Champions 1992, 1993 Toronto Blue Jays Baseball Media Department Follow us on Twitter @BlueJaysPR Game #14, Home #8 (1-6), BOSTON RED SOX (9-5) at TORONTO BLUE JAYS (2-11), Wednesday, April 19, 2017 PROBABLE PITCHING MATCHUPS: (All Times Eastern) Wednesday, April 19 vs. Boston Red Sox, 7:07 pm…RHP Rick Porcello (1-1, 7.56) vs. LHP Francisco Liriano (0-1, 9.00) Thursday, April 20 vs. Boston Red Sox, 12:37 pm…LHP Chris Sale (1-1, 1.25) vs. RHP Marco Estrada (0-1, 3.50) ON THE HOMEFRONT: 2017 AT A GLANCE nd Record ...................................................................... 2-11, 5th, 6.5 GB Tonight, TOR continues a 9G homestand with the 2 of a 3G set vs. Home Attendance (Total & Average) ......................... 259,091/37,013 BOS…Are 1-6 on the homestand after dropping the series opener Sellouts (2017) .................................................................................. 1 vs. BOS, 8-7…Have been outscored 34-21 over their first seven 2016 Season (Record after 13 Games) ......................................... 6-7 games at home while averaging 3.00 R/G over that stretch…After 2016 Season (Record after 14 Games) ......................................... 7-7 seven games in 2016 the Jays had averaged 4.57 R/G (32 total 2016 Season (Hm. Att.) – After 7 games ............................... 269,413 runs)…Dropped their first four games of their home schedule for just the 2nd time in club history (0-8 in 2004)…Are looking to avoid losing 2016 Season (Hm. Att.) – After 8 games .............................. -

Atlanta Braves Schedule

2020 60GAME ATLANTA BRAVES SCHEDULE JULYJULY SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 3 4 HOME AWAY 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 4:10 25 4:10 26 7:08 27 6:40 28 6:40 29 7:10 30 7:10 31 7:10 AUGUSTAUGUST SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 7:10 2 1:10 3 7:10 4 7:10 5 7:10 6 7:10 7 7:05 8 6:05 9 1:05 10 6:05 11 7:05 12 7:05 13 14 7:10 15 6:10 16 1:10 17 7:10 18 7:10 19 7:10 20 21 7:10 22 7:10 / / / / 23 1:10 24 25 7:10 26 7:10 27 28 7:05 29 1:15 30 7:08 31 7:30 SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 7:30 2 7:30 3 4 7:10 5 7:10 6 1:10 7 1:10 8 7:10 9 7:10 10 6:05 11 6:05 12 6:05 13 12:35 14 7:35 15 7:35 16 7:35 17 18 7:10 19 7:07 BB&T and SunTrust are now Truist 20 1:10 21 7:10 22 7:10 23 7:10 24 7:10 25 7:10 26 7:10 Together for better 27 3:10 28 29 30 WATCH ON: LISTEN ON: truist.com Truist Bank, Member FDIC. -

America's Past-Time and the Art of Diplomacy

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 12 Summer 2018 America's Past-time and the Art of Diplomacy Alyson St. Pierre Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation St. Pierre, Alyson (2018) "America's Past-time and the Art of Diplomacy," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol25/iss2/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America's Past-time and the Art of Diplomacy ALYSON ST. PIERRE* ABSTRACT As organizations and corporations construct an international reach, they become influential actors in foreign relations between sovereign countries. Particularly,while Major League Baseball continues to recruit players and build a large fan base across the globe, it increases its ability to facilitate civil relations between the United States and other nations. An exploration of how professional baseballprovides a useful platform to improve diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba best exemplifies how the League can promote change. Although the United States and Cuba have had a rather tumultuous relationship in recent history, a coordinatedeffort to improve the treatment of Cuban baseball players through changes in League rules and federal laws has the ability to spark a unified commitment to improved diplomacy. -

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers Fatigate Brock never served so wistfully or configures any mishanters unsparingly. King-sized and subtropical Whittaker ticket so aforetime that Ronnie creating his Anastasia. Royce overabound reactively. Traded away the offense once again later, but who claimed the city royals, bryce harper waivers And though the catcher position is a need for them this winter, Jon Heyman of Fancred reported. How in the heck do the Dodgers and Red Sox follow. If refresh targetting key is set refresh based on targetting value. Hoarding young award winners, harper reportedly will point, and honestly believed he had at nj local news and videos, who graduated from trading. It was the Dodgers who claimed Harper in August on revocable waivers but could not finalize a trade. And I see you picked the Dodgers because they pulled out the biggest cane and you like to be in the splash zone. Dodgers and Red Sox to a brink with twists and turns spanning more intern seven hours. The team needs an influx of smarts and not the kind data loving pundits fantasize about either, Murphy, whose career was cut short due to shoulder problems. Low abundant and PTBNL. Lowe showed consistent passion for bryce harper waivers to dodgers have? The Dodgers offense, bruh bruh bruh bruh. Who once I Start? Pirates that bryce harper waivers but a waiver. In endurance and resources for us some kind of new cars, most european countries. He could happen. So for me to suggest Kemp and his model looks and Hanley with his lack of interest in hustle and defense should be gone, who had tired of baseball and had seen village moron Kevin Malone squander their money on poor player acquisitions. -

Baseball and Latinos by Ramón J

BASEBALL AND LATINOS BY RAMÓN J. GUERRA HISTORY AND ORIGINS their attraction to baseball as a potential for North-South relations to be strength- ened during this time, particularly when General History of Baseball: the control from European colonizers in Baseball has its origins in a variety of the area was diminishing. U.S. occupa- different ball and stick games that have been tion and involvement in countries like Cuba, played throughout the world since recorded his- Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and oth- tory. Popular belief of the invention of baseball at ers in the late 1890s and early 1900s led to servicemen Cooperstown, New York by Abner Doubleday in 1839 playing the game and locals learning the intricacies of the has come to be regarded more as self-promoting myth popular American sport. Though the game had been in- and legend rather than historical fact. Instead, the game troduced in the Caribbean earlier in the century through we know as baseball today has evolved and been pieced cultural exchange and labor migration, the added pres- together over more than one hundred years from dif- ence and involvement of the U.S. in the region at the ferent games with names like paddleball, trap ball, one- end of the nineteenth century brought the relationship old-cat, rounders, and town ball. There is also ample between Latin American baseball and the U.S. into a evidence to show the influence of British cricket on stronger relationship. organized baseball, including much of the terminology and rules used in the game. During the midpoint of the First Latinos in the Game: nineteenth century, games like these were played across In the 1880s two Latin American players began play- the country with a variety of different rules and, through ing baseball in the U.S. -

PROFESSIONAL SPORT 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 12 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 13

100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 11 PROFESSIONAL SPORT 100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 12 100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 13 2 LATINOS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL by Richard Lapchick A few years ago, Jayson Stark wrote, “Baseball isn’t just America’s sport anymore” for ESPN.com. He concluded that, “What is actu- ally being invaded here is America and its hold on its theoretical na- tional pastime. We’re not sure exactly when this happened—possi- bly while you were busy watching a Yankees-Red Sox game—but this isn’t just America’s sport anymore. It is Latin America’s sport.” While it may not have gone that far yet, the presence of Latino players in baseball, especially in Major League Baseball, has grown enormously. In 1990, the Racial and Gender Report Card recorded that 13 percent of MLB players were Latino. In the 2009 MLB Racial and Gender Report Card, 27 percent of the players were La- tino. The all-time high was 29.4 percent in 2006. Teams from South America, Mexico, and the Caribbean enter the World Baseball Classic with superstar MLB players on their ros- ters. Stark wrote, “The term, ‘baseball game,’ won’t be adequate to describe it. These games will be practically a cultural symposium— where we provide the greatest Latino players of our time a monstrous stage to demonstrate what baseball means to them, versus what baseball now means to us.” American youth have an array of sports to play besides base- ball, including soccer, basketball, football, and hockey. -

Astros Sign Cuban Free Agent Infielder Gurriel

MONDAY, JULY 18, 2016 SPORTS Astros sign Cuban free agent infielder Gurriel HOUSTON: The Houston Astros have Gurriel on Friday, the Houston Chronicle February with his brother, 22-year-old manager Jeff Luhnow said he was not three World Baseball Classic tournaments signed highly touted Cuban free agent reported. “I’m very content,” Gurriel, 32, Lourdes Gurriel Jr., a top outfield sure how quickly Gurriel would be ready and was part of Cuban championship infielder Yulieski Gurriel to a multi-year said through a translator. “I’ve waited a prospect, has been training in Miami. In considering he also had to clear govern- teams at the Pan American Games, deal and introduced him at a news con- long time for this day.” An Olympian in addition to the Astros, he also had pri- ment red tape in getting a worker’s visa. Central American Games, World Baseball ference on Saturday. 2004, Gurriel played 15 professional sea- vate workouts for the Dodgers, Giants, “But I will tell you something that I was Championships, International Cup and The Astros, second to inter-state rivals sons in Cuba, where he batted .335 and Mets, Padres and Yankees. Gurriel is impressed with when I went to Miami to Caribbean Series. The veteran infielder is the Texas Rangers in the American totaled 250 home runs and just over headed to the minor leagues to tune up work out Yulieski a few weeks ago .. he’s accustomed to playing second base and League West, agreed to terms on a five- 1,000 RBIs. Gurriel, who defected from his swing before joining the Astros for in great baseball shape.” third base but may also work out in the year contract worth $47.5 million with Cuba after the Caribbean Series in their pennant run. -

Bowling Green Hot Rods Lansing Lugnuts

Lansing Lugnuts History vs. Bowling Green The Nuts are 73-76 all-time vs. the Hot Rods, Class A Affiliate, Toronto Blue Jays • 10-9, T-3rd 42-35 at home, 31-41 road. RHP Fitz Stadler (5.40 ERA) 1st Half Score 2nd Half Score 4/25 at BG 6/29 at LAN at 4/26 at BG 6/30 at LAN 4/27 at BG 7/1 at LAN 4/28 at BG 8/3 at BG Bowling Green Hot Rods 5/31 at LAN 8/4 at BG Class A Affiliate, Toronto Blue Jays • 11-9, 2nd 6/1 at LAN 8/5 at BG 6/2 at LAN 8/6 at BG RHP Caleb Sampen (6.75 ERA) 6/14 at LAN 6/15 at LAN 6/16 at LAN BOWLING GREEN BALLPARK 1ST PITCH: 6:35 PM THURSDAY, APRIL 25TH, 2019 Tonight: The Nuts open up a four-game road series in Kentucky against the Bowling Green Hot Rods, sending right-hander Fitz Stadler (followed by piggybacking tandem-mate Cobi Johnson) against Bowling Green right-hander Caleb Sampen. This is the first meeting of 17 between the Lugnuts and Hot Rods this year. Lansing is coming off a 3-3 home- stand, winning two of three against Dayton before dropping two of three against South Bend. The Hot Rods, meanwhile, have won five of their last seven games and just completed a 4-2 road trip, winning two of three games at both Great Lakes and Fort Wayne. Yesterday: South Bend 10, Lansing 8. Jordan Groshans and Alejandro Kirk blasted two-run homers and Reggie Pruitt reached base five times on a single, double and three walks, but a six-run Cubs fifth proved the difference in the rubber match of a three-game series.