PROFESSIONAL SPORT 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 12 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cubs Win the World Series!

Can’t-miss listening is Pat Hughes’ ‘The Cubs Win the World Series!’ CD By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Monday, January 2, 2017 What better way for Pat Hughes to honor his own achievement by reminding listeners on his new CD he’s the first Cubs broadcaster to say the memorable words, “The Cubs win the World Series.” Hughes’ broadcast on 670-The Score was the only Chi- cago version, radio or TV, of the hyper-historic early hours of Nov. 3, 2016 in Cleveland. Radio was still in the Marconi experimental stage in 1908, the last time the Cubs won the World Series. Baseball was not broadcast on radio until 1921. The five World Series the Cubs played in the radio era – 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945 – would not have had classic announc- ers like Bob Elson claiming a Cubs victory. Given the unbroken drumbeat of championship fail- ure, there never has been a season tribute record or CD for Cubs radio calls. The “Great Moments in Cubs Pat Hughes was a one-man gang in History” record was produced in the off-season of producing and starring in “The Cubs 1970-71 by Jack Brickhouse and sidekick Jack Rosen- Win the World Series!” CD. berg. But without a World Series title, the commemo- ration featured highlights of the near-miss 1969-70 seasons, tapped the WGN archives for older calls and backtracked to re-creations of plays as far back as the 1930s. Did I miss it, or was there no commemorative CD with John Rooney, et. -

Believe: the Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" by David J

Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" By David J. Fletcher, CBM President Posted Sunday, April 12, 2015 Disheartened White Sox fans, who are disappointed by the White Sox slow start in 2015, can find solace in Sunday night’s television premiere of “Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" that airs on Sunday night April 12th at 7pm on Comcast Sports Net Chicago. Produced by the dynamic CSN Chi- cago team of Sarah Lauch and Ryan Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox will air McGuffey, "Believe" is an emotional on Sunday, Apr. 12 at 7:00pm CT, on Comcast Sportsnet. roller-coaster-ride of a look at a key season in Chicago baseball history that even the casual baseball fan will enjoy because of the story—a star-crossed team cursed by the 1919 Black Sox—erases 88 years of failure and wins the 2005 World Series championship. Lauch and McGuffey deliver an extraordinary historical documentary that includes fresh interviews with all the key participants, except pitcher Mark Buehrle who declined. “Mark respectfully declined multiple interview requests. (He) wanted the focus to be on his current season,” said McGuffey. Lauch did reveal “that Buehrle’s wife saw the film trailer on the Thursday (April 9th) and loved it.” Primetime Emmy & Tony Award winner, current star of Showtime’s acclaimed drama series “Homeland”, and lifelong White Sox fan Mandy Patinkin, narrates the film in an under-stated fashion that retains a hint of his Southside roots and loyalties. The 76 minute-long “Believe” features all of the signature -

How to Write a Case Study

Swing, Batter, Batter, Swing! 9 business tips borrowed from Major League Baseball Swing, Batter, Batter, Swing! Summer is officially upon us, and the Boys of Summer are in action on fields of dreams across the country. One of the greatest hitters in the history of the baseball, new Kansas City Royals batting coach George Brett, believes home runs are the product of a good swing. Take good swings and home runs will happen. It’s great to get on base but it’s better to hit homers. Home Run Power -- hitting balls harder, farther and more consistently – takes practice. And there is a science to being a successful slugger. From Hank Aaron and Barry Bonds to Ty Cobb and Hugh Duffy, companies that want to knock the cover off the ball can learn plenty from legendary MLB players. Most baseball games have nine innings (although I recently sweated thru a 13-inning Padres versus the Giants stretch) so here are nine tips: 1. Focus on good hitting. You get more home runs when you stop trying for them and focus on good hitting instead. Making progress in business is no different; aim for competence and get the basics right. Strive for everyday improvements and great execution. Adap.tv, a video advertising platform predicted to IPO in 2013, releases new code over 10 times a day to heighten continuous innovation. Akin to batting practice for the serious ball player. Goals without great execution are just dreams. According to research conducted by noted business author and advisor, Ram Charan, 70% of CEOs who fail do so not because of bad strategy, but because of bad execution. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Probable Starting Pitchers 31-31, Home 15-16, Road 16-15

NOTES Great American Ball Park • 100 Joe Nuxhall Way • Cincinnati, OH 45202 • @Reds • @RedsPR • @RedlegsJapan • reds.com 31-31, HOME 15-16, ROAD 16-15 PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Sunday, June 13, 2021 Sun vs Col: RHP Tony Santillan (ML debut) vs RHP Antonio Senzatela (2-6, 4.62) 700 wlw, bsoh, 1:10et Mon at Mil: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez (2-1, 2.65) vs LHP Eric Lauer (1-2, 4.82) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Great American Ball Park Tue at Mil: RHP Luis Castillo (2-9, 6.47) vs LHP Brett Anderson (2-4, 4.99) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Wed at Mil: RHP Tyler Mahle (6-2, 3.56) vs RHP Freddy Peralta (6-1, 2.25) 700 wlw, bsoh, 2:10et • • • • • • • • • • Thu at SD: LHP Wade Miley (6-4, 2.92) vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et CINCINNATI REDS (31-31) vs Fri at SD: RHP Tony Santillan vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et Sat at SD: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez vs TBD 700 wlw, FOX, 7:15et COLORADO ROCKIES (25-40) Sun at SD: RHP Luis Castillo vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, mlbn, 4:10et TODAY'S GAME: Is Game 3 (2-0) of a 3-game series vs Shelby Cravens' ALL-TIME HITS, REDS CAREER REGULAR SEASON RECORD VS ROCKIES Rockies and Game 6 (3-2) of a 6-game homestand that included a 2-1 1. Pete Rose ..................................... 3,358 All-Time Since 1993: ....................................... 105-108 series loss to the Brewers...tomorrow night at American Family Field, 2. Barry Larkin ................................... 2,340 At Riverfront/Cinergy Field: ................................. -

Game Day Information

GAME DAY INFORMATION Ron Tonkin Field | 4460 NW 229th Ave. | Hillsboro, OR 97124 | 503-640-0887 www.HillsboroHops.com | @HillsboroHops | Class-A Affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks Northwest League Champions 2014, 2015 HILLSBORO HOPS AT EUGENE EMERALDS Saturday, July 7 to Monday, July 9, 2018 ● P.K. Park, Eugene, Oregon Games #23-25 (15-7 entering series) ● Road Games #12-14 (7-4 entering series) HOPS TRAVEL TO EUGENE FOR FIRST TIME IN 2018 THIS SERIES: The Hops and Eugene PLAYING (AND WINNING) IT CLOSE: Emeralds meet for their second series of The Hops have played the most one-run 1ST-HALF STANDINGS THRU 7/6 the year; Eugene took 2 of 3 at Ron Tonkin games in the NWL in 2018 (9, tied with SOUTH W L PCT GB Field from June 20-22; the Ems had also Salem-Keizer), and Hillsboro has the best Hillsboro (ARI) 15 7 .682 --- won their first series of the year in record in the NWL in one-run games (8- Salem-Keizer (SF) 13 9 .591 2.0 Vancouver June 15-19; but since winning 1). That also fits with the historical trend: Boise (COL) 12 10 .545 3.0 Eugene (CHC) 8 14 .364 7.0 those first two series, Eugene has dropped incredibly, since entering the league in four series in a row. 2013, the Hops are THIRTY-FOUR games NORTH W L PCT GB above .500 in one-run games (79-45). Everett (SEA) 12 10 .545 --- Tri-City (SD) 10 12 .455 2.0 MAYBE NOT ON THE HOME STRETCH Vancouver (TOR) 10 12 .455 2.0 YET… but with 16 games remaining in the VS. -

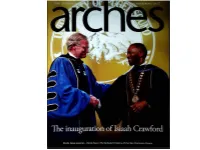

Spring 2017 Arches 5 WS V' : •• Mm

1 a farewell This will be the last issue o/Arches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefton. On the cover: President EmeritusThomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. Conference Women s Basketball Tournament versus Lewis & Clark. After being behind nearly the whole —. game and down by 10 with 3:41 left in the fourth |P^' quarter, the Loggers start chipping away at the lead Visit' and tie the score with a minute to play. On their next possession Jamie Lange '19 gets the ball under the . -oJ hoop, puts it up, and misses. She grabs the rebound, Her second try also misses, but she again gets the : rebound. A third attempt, too, bounces around the rim and out. For the fourth time, Jamie hauls down the rebound. With 10 seconds remaining and two defenders all over her, she muscles up the game winning layup. The crowd, as they say, goes wild. RITE OF SPRING March 18: The annual Puget Sound Women's League flea market fills the field house with bargain-hunting North End neighbors as it has every year since 1968 All proceeds go to student scholarships. photojournal A POST-ELECTRIC PLAY March 4: Associate Professor and Chair of Theatre Arts Sara Freeman '95 directs Anne Washburn's hit play, Mr. Burns, about six people who gather around a fire after a nationwide nuclear plant disaster that has destroyed the country and its electric grid. For comfort they turn to one thing they share: recollections of The Simpsons television series. The incredible costumes and masks you see here were designed by Mishka Navarre, the college's costumer and costume shop supervisor. -

Insert Text Here

TROUT AT 1,000 CAREER GAMES On June 21st, Angels outfielder Mike Trout played in his 1,000th career game. Since making his debut July 8, 2011, the Millville, NJ native amassed a .308 (1,126/3,658) average with 216 doubles, 43 triples, 224 home runs, 617 RBI, 178 stolen bases and 754 runs scored during his first 1,000 games. Below you will find a summary of some of Trout’s accomplishments: His 224 career home runs were tied with Joe DiMaggio for 17th most all- MLB ALL-TIME LEADERS & THEIR time by an American Leaguer in their first 1,000 career games…MLB TOTALS AT 1,000 GAMES* home run leader, Barry Bonds, had 172 career home runs after his LEADER TROUT 1,000th career game. H PETE ROSE, 1,231 1,126 HR BARRY BONDS, 172 224 R RICKEY HENDERSON, 795 754 754 runs are the 20th most in Major League history by a player in their BB BARRY BONDS, 603 638 th TB HANK AARON, 2,221 2,100 first 1,000 career games and 14 in A.L. history…Trout scored more runs WAR BARRY BONDS, 50 60.8 in his first 1,000 career games than Stan Musial (746), Jackie Robinson * COURTESY OF ESPN (743), Willie Mays (719) and Frank Robinson (706), among others…Rickey Henderson, who has scored the most runs in Major League history, had 795 career runs at the time of his 1,000th career game. Trout has amassed 2,100 total bases, ranking 17th all-time by an PLAYERS WITH 480+ EXTRA-BASE HITS American Leaguer in their first 1,000 career games, ahead of Ken Griffey & 600 WALKS IN FIRST 1,000 G Jr. -

1962 Topps Baseball "Bucks" Set Checklist

1962 TOPPS BASEBALL "BUCKS" SET CHECKLIST NNO Hank Aaron NNO Joe Adcock NNO George Altman NNO Jim Archer NNO Richie Ashburn NNO Ernie Banks NNO Earl Battey NNO Gus Bell NNO Yogi Berra NNO Ken Boyer NNO Jackie Brandt NNO Jim Bunning NNO Lou Burdette NNO Don Cardwell NNO Norm Cash NNO Orlando Cepeda NNO Bob Clemente NNO Rocky Colavito NNO Chuck Cottier NNO Roger Craig NNO Bennie Daniels NNO Don Demeter NNO Don Drysdale NNO Chuck Estrada NNO Dick Farrell NNO Whitey Ford NNO Nellie Fox NNO Tito Francona NNO Bob Friend NNO Jim Gentile NNO Dick Gernert NNO Lenny Green NNO Dick Groat NNO Woodie Held NNO Don Hoak NNO Gil Hodges NNO Elston Howard NNO Frank Howard NNO Dick Howser NNO Ken L. Hunt NNO Larry Jackson NNO Joe Jay Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 NNO Al Kaline NNO Harmon Killebrew NNO Sandy Koufax NNO Harvey Kuenn NNO Jim Landis NNO Norm Larker NNO Frank Lary NNO Jerry Lumpe NNO Art Mahaffey NNO Frank Malzone NNO Felix Mantilla NNO Mickey Mantle NNO Roger Maris NNO Eddie Mathews NNO Willie Mays NNO Ken McBride NNO Mike McCormick NNO Stu Miller NNO Minnie Minoso NNO Wally Moon NNO Stan Musial NNO Danny O'Connell NNO Jim O'Toole NNO Camilo Pascual NNO Jim Perry NNO Jim Piersall NNO Vada Pinson NNO Juan Pizarro NNO Johnny Podres NNO Vic Power NNO Bob Purkey NNO Pedro Ramos NNO Brooks Robinson NNO Floyd Robinson NNO Frank Robinson NNO Johnny Romano NNO Pete Runnels NNO Don Schwall Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2. -

Otis' Hit Lifts K.C. Over Seattle

Otis' hit lifts K.C. over Seattle Ihrited Press International two-o-ut walk in the fifth and took third knocked in the first run with a fielder's on Al Bumbry's double. Rich choice grounder and Dan Ford followed KANSAS CITY, Mo. American Loatfue Dauer Amos Otis' then singled across both to with an RBI single. An RBI single eighth-innin- g runners pull by RBI single 4-- snapped a 4 3-- g came on a triple by Joe Zbed and double the Orioles within 2. Don Baylor and a run-scorin- double by and Dennis tie Leonard scattered seven by U.L. Washington in the second. Willie Aikens capped the inning. hits Thursday night, pacing the 6 Brewers 9, 1-- Kansas Angels Jerry Augustine pitched the final 4 3 Royals to 5-- 4 City a victory over the Orioles 5, Red Sox 3 MILWAUKEE Ben Oglivie innings in relief of Haas, scattering five Seattle Mariners. - BALTIMORE Kiko Garcia slammed a three-ru- n homer to ignite a hits and yielding one run to record his Pinch-hitt- er Steve Braun opened n, the slammed a two-ru- sixth-innin- g home five-ru- n third inning and Sal Bando second win in four decisions. eighth against loser Odell Jones, 0-- 5, run and Dennis Martinez won his belted a solo homer to pace a 14-h- it with a single. He was replaced by Fred seventh straight game to lead attack, powering Milwaukee over White Sox 10, A'sl Patek, who took second on a three-gam- sacrifice Baltimore to a come-from-behi- nd California and a e sweep of CHICAGO Lamar Johnson drove in bunt by Willie Wilson. -

2019 Topps Diamond Icons BB Checklist

AUTOGRAPH AUTOGRAPH CARDS AC-AD Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® AC-AJU Aaron Judge New York Yankees® AC-AK Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® AC-AP Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® AC-ARI Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® AC-ARO Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® AC-BG Bob Gibson St. Louis Cardinals® AC-BJ Bo Jackson Kansas City Royals® AC-BL Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® AC-CF Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® AC-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ AC-CK Corey Kluber Cleveland Indians® AC-CKE Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® AC-CR Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® AC-CS Chris Sale Boston Red Sox® AC-DE Dennis Eckersley Oakland Athletics™ AC-DMA Don Mattingly New York Yankees® AC-DMU Dale Murphy Atlanta Braves™ AC-DO David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® AC-DP Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® AC-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® Rookie AC-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ AC-FF Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ AC-FL Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® AC-FM Fred McGriff Atlanta Braves™ AC-FT Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® AC-FTJ Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ Rookie AC-GSP George Springer Houston Astros® AC-HA Hank Aaron Atlanta Braves™ AC-HM Hideki Matsui New York Yankees® AC-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ AC-JA Jose Altuve Houston Astros® AC-JBA Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® AC-JBE Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® AC-JC Jose Canseco Oakland Athletics™ AC-JD Jacob deGrom New York Mets® AC-JDA Johnny Damon Boston Red Sox® AC-JM Juan Marichal San Francisco Giants® AC-JP Jorge Posada New York Yankees® AC-JS John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ AC-JSO Juan Soto Washington Nationals® AC-JV Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® AC-JVA Jason Varitek Boston Red Sox® AC-KB Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® AC-KS Kyle Schwarber Chicago Cubs® AC-KT Kyle Tucker Houston Astros® Rookie AC-LB Lou Brock St.