The Best Interests of Baseball Clause and the Astros' "High Tech" Sign-Stealing Scandal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test

The “Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test One of the many beauties of baseball, affectionately known as “America’s pastime,” is the ability for people to come to the stadium and become ingrained in the action and get the chance to interact with their heroes. Going to a baseball game, as opposed to going to most other sporting events, truly gives a fan the opportunity to take part in the action. However, this can come at a steep price as foul balls enter the stands at alarming speeds and occasionally strike spectators. According to a recent study, approximately 1,750 people get hurt each year by batted 1 balls at Major League Baseball (MLB) games, which adds up to twice every three games. The 2015 MLB season featured many serious incidents that shed light on the issue of 2 spectator protection. This has led to heated debates among the media, fans, and even players and 3 managers as to what should be done to combat this issue. Currently, there is a pending class action lawsuit against Major League Baseball (“MLB”). The lawsuit claims that MLB has not 1 David Glovin, Baseball Caught Looking as Fouls Injure 1,750 Fans a Year, BLOOMBERG BUSINESS (Sept. 9, 2014, 4:05 PM), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/20140909/baseballcaughtlookingasfoulsinjure1750fansayear. 2 On June 5, a woman attending a Boston Red Sox game was struck in the head by a broken bat that flew into the seats along the third baseline. See Woman hurt by bat at Red Sox game released from hospital, NEW YORK POST (June 12, 2015, 9:32 PM), http://nypost.com/2015/06/12/womanhurtbybatatredsoxgamereleasedfromhospital/. -

Lewiston Evening Teller

v-C-V> LEWISTON EVENING TELLER. MONDAY, JULY 4, 1M4 day when “Old Cy" Young performed a “Anything else that helped?” feat, the l'ke of which the diamond has “Yep. fine day—warm." The Raymond The Palace- MAKING A USE not known in twenty-four years. It “Anything else?" Tra'W M juiw acA j to neii.s.Mmcrf) »nt , • • * » «•. came this day when “Old Cy" Young FINE SHOOT "Not much wind.” •TEAM HEAT, ELECTRIC LICHTE F. ROOS, PROPRI1 Climbed upon a pedestal upon which “Well?” FREE CUE AND BATHE OOOC only two ball twlrlers of the past ever •AMPLE ROOM«. Cedar L ook KcBrayar WhbRHR MLLJECORD climbed. “Felt good.” “Like baseball?” YESTERDAY j Beeten «A r*. * 'W Rates $8 M and 9AM per day. The feat that he performed was by “Best sport in the world.” the wonder of his ball twirling to cut “Ever get tired of it?" C. W. BURDICK. Propletor. Main BtrooL band m t Third. ,7 O l d “Cy” Young Tells Charles entirely out of all chance in the game “Only one part.” N- Butler Won the Hunter ' ................ ....... y •.. one of the best ball teams In America, “What part?" Somerville How He the Athletics of Philadelphia. "Posin' for my picture." Arms Medal in a C lo s e The Pacific Bor From this veteran of the diamond And the monosyllabic “Cy” got up ir YOU WANT TO KEEP IN TOUCH D id I t not one of the swatstick artists, not the WITH THE GREAT SOUTHWEST from the bench and walked to the C o n t e s t -■ «»M ato'S*-^ M”’*' finest of them, even so much as saw coacher's box. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Clearbuck.Com Update

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball ClearBuck.com Update Friday, May 21, 2004 Issue 6 ClearBuck.com on "The AL Central Today Show" Champs Who will win ClearBuck.com ambassadors the AL Central? battled the early morning cold Indians and ventured out to the Tribune plaza where "The Royals Today Show" taped live. Tigers Katie Couric and Al Roker helped celebrate the Twins destruction of the Bartman White ball with fellow Chicago Sox baseball fans. Look carefully in the audience for the neon green Clear Buck! signs. Thanks to Allison Donahue of Serafin & Associates for the 4:00 a.m. wakeup. [See Results] Black Sox historian objects to glorification of Comiskey You Can Help Statue condones Major League Baseball’s cover-up of 1919 World Series Download the Petition To the dismay of Black Sox historian and ClearBuck.com founder Dr. David Fletcher, Find Your Legislator the Chicago White Sox will honor franchise founder Charles A. Comiskey on April 22, Visit MLB for Official 2004 with a life-sized bronze statue. Information Contact Us According to White Sox chairman Jerry Reinsdorf, Comiskey ‘played an important role in the White Sox organization.’ Dr. Fletcher agrees. “Charles Comiskey engineered Visit Our Site the cover-up of one of the greatest scandals in sports history – the 1919 World Series Discussion Board Black Sox scandal. Honoring Charles Comiskey is like honoring Richard Nixon for his role in Watergate.” Photo Gallery Broadcast Media While Dr. Fletcher acknowledges Comiskey’s accomplishments as co-founder of the American League and the Chicago White Sox, his masterful cover-up of the series contributed to Buck Weaver’s banishment from Major League Baseball. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Time to Drop the Infield Fly Rule and End a Common Law Anomaly

A STEP ASIDE TIME TO DROP THE INFIELD FLY RULE AND END A COMMON LAW ANOMALY ANDREW J. GUILFORD & JOEL MALLORD† I1 begin2 with a hypothetical.3 It’s4 the seventh game of the World Series at Wrigley Field, Mariners vs. Cubs.5 The Mariners lead one to zero in the bottom of the ninth, but the Cubs are threatening with no outs and the bases loaded. From the hopeful Chicago crowd there rises a lusty yell,6 for the team’s star batter is advancing to the bat. The pitcher throws a nasty † Andrew J. Guilford is a United States District Judge. Joel Mallord is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a law clerk to Judge Guilford. Both are Dodgers fans. The authors thank their friends and colleagues who provided valuable feedback on this piece, as well as the editors of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review for their diligent work in editing it. 1 “I is for Me, Not a hard-hitting man, But an outstanding all-time Incurable fan.” OGDEN NASH, Line-Up for Yesterday: An ABC of Baseball Immortals, reprinted in VERSUS 67, 68 (1949). Here, actually, we. See supra note †. 2 Baseball games begin with a ceremonial first pitch, often resulting in embarrassment for the honored guest. See, e.g., Andy Nesbitt, UPDATE: 50 Cent Fires back at Ridicule over His “Worst” Pitch, FOX SPORTS, http://www.foxsports.com/buzzer/story/50-cent-worst-first-pitch-new-york- mets-game-052714 [http://perma.cc/F6M3-88TY] (showing 50 Cent’s wildly inaccurate pitch and his response on Instagram, “I’m a hustler not a damn ball player. -

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

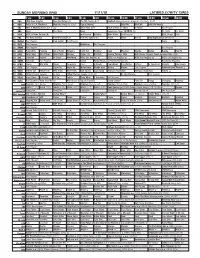

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Miranda V. Selig

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT SERGIO MIRANDA; JEFFREY No. 15-16938 DOMINGUEZ; JORGE PADILLA; and CIRILO CRUZ, Individually D.C. No. and on Behalf of All Those 3:14-cv-05349-HSG Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs-Appellants, OPINION v. ALLAN HUBER SELIG, Bud; KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL CORP.; MIAMI MARLINS, L.P.; SAN FRANCISCO BASEBALL ASSOCIATES, LLC; BOSTON RED SOX BASEBALL CLUB L.P.; ANGELS BASEBALL L.P.; CHICAGO WHITE SOX LTD.; ST. LOUIS CARDINALS, LLC; COLORADO ROCKIES BASEBALL CLUB, LTD.; BASEBALL CLUB OF SEATTLE, LLP; CINCINNATI REDS, LLC; HOUSTON BASEBALL PARTNERS, LLC; ATHLETICS INVESTMENT GROUP, LLC; ROGERS BLUE JAYS BASEBALL PARTNERSHIP; CLEVELAND INDIANS BASEBALL CO., L.P.; CLEVELAND INDIANS BASEBALL CO., INC.; PADRES 2 MIRANDA V. SELIG L.P.; SAN DIEGO PADRES BASEBALL CLUB, L.P.; MINNESOTA TWINS, LLC; WASHINGTON NATIONALS BASEBALL CLUB, LLC; DETROIT TIGERS, INC.; LOS ANGELES DODGERS HOLDING CO.; STERLING METS L.P.; ATLANTA NATIONAL LEAGUE BASEBALL CLUB, INC.; AZPB L.P.; BALTIMORE ORIOLES, INC.; BALTIMORE ORIOLES, L.P.; PHILLIES L.P.; PITTSBURGH BASEBALL, INC.; PITTSBURGH BASEBALL P’SHIP; NEW YORK YANKEES P’SHIP; TAMPA BAY RAYS BASEBALL LTD.; RANGERS BASEBALL EXPRESS, LLC; RANGERS BASEBALL, LLC; CHICAGO BASEBALL HOLDINGS, LLC; MILWAUKEE BREWERS BASEBALL CLUB, INC.; MILWAUKEE BREWERS BASEBALL CLUB, L.P.; OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, DBA Major League Baseball; LOS ANGELES DODGERS, LLC, Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of California Haywood S. Gilliam, Jr., District Judge, Presiding MIRANDA V. SELIG 3 Argued and Submitted April 18, 2017 San Francisco, California Filed June 26, 2017 Before: Sidney R.