Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football Natalie M

Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 8 9-1-1995 Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football Natalie M. Gurdak Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tjcil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Natalie M. Gurdak, Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football, 3 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int'l L. 121 (1995). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tjcil/vol3/iss1/8 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact daniel- [email protected]. BASEBALL, HOT DOGS, APPLE PIE, AND STRIKES: HOW BASEBALL COULD HAVE AVOIDED THEIR LATEST STRIKE BY STUDYING SPORTS LAW FROM BRITISH FOOTBALL I. INTRODUCTION At the end of the 1994 Major League Baseball Season, the New York Yankees and the Montreal Expos had the best records in the American and National Leagues, respectively.' However, neither team made it to the World Series.2 Impossible, you say? Not during the 1994 season, which ended abruptly in August due to a players' strike.' As the players and owners disputed over financial matters, fans were deprived of a World Series for the second time in the history of the game.4 America's favorite pastime was in peril. -

Instituto Laboral De La Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards

Instituto Laboral de la Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards Friday, February 18th, 2011 Reception and Media Coverage: 5:00pm Dinner and Awards: 6:30pm Hotel Marriott Marquis — San Francisco 55 Fourth Street, San Francisco, CA 2011 Honorees GUEST OF HONOR & LABOR LEADER OF THE YEAR Edwin D. Hill LA RAZA CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP AWARD Senator Barbara Boxer (US Senate, CA) LA RAZA CIVIL RIGHTS AWARD Alice A. Huffman JIM RUSH LABOR AND COMMUNITY ACTIVIST AWARD Earl “Marty” Averette LA RAZA SAN PATRICIO LEADERSHIP AWARD George Landers LA RAZA CORPORATE LEADERSHIP AWARD Josh Becker CURT FLOOD LABOR-COMMUNITY AWARD Major League Baseball Players Association Welcome Instituto Laboral de la Raza Instituto Laboral de la Raza STAFF 2947 16th STREET • SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103 SARAH M. SHAKER Dear Labor Friends and Supporters: Executive Director Welcome to the Instituto Laboral de la Raza’s 2011 National Labor-Community Awards. This evening we BRIAN E. WEBSTER honor Edwin D. Hill, International President of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, our Chief of Staff and Events Manager Guest of Honor and Labor Leader of the Year. According to the Huffington Post, President Hill “is a leading voice for a balanced and practical approach to the nation’s pursuit of energy independence“... and he expands “the role of job training … seeking to combat global warming.” DOUG HAAKE WALTER SANCHEZ Legal Aid Legal Aid and Program Manager We are very proud of our U.S. Senator, Barbara Boxer (D-CA). Senator Boxer is a true fighter for liberal causes. Senator Boxer, like the late Senator Ted Kennedy, truly cares for the rights of the working man and ROSA ARGENTINA OATES ISENIA D. -

Spring 2009 Issue of the University of Denver Sports and Entertainment

UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 6 Spring 2009 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE EDITOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 ARTICLES MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULE: WHERE ARE WE NOW? ………………………..3 Harvey Gilmore GREAT EXPECTATIONS: CONTENT REGULATION IN FILM, RADIO, AND TELEVISION…………………….31 Alexandra Gil “FROM RUSSIA” WITHOUT LOVE: CAN THE SHCHUKIN HEIRS RECOVER THEIR ANCESTOR’S ART COLLECTION?………………………………………………..…………………………………...65 Jane Graham OPPORTUNISM, UNCERTAINTY AND RELATIONAL CONTRACTING – ANTITRUST IN THE FILM INDUSTRY………………………………………………………………………………………107 Ryan M. Riegg SHOULD THE GOVERNMENT FLEX ITS MUSCLES AND REGULATE STEROIDS N BASEBALL? WEAKNESSES IN THE PUBLIC HEALTH ARGUMENT......………………………………………………………………151 Connor Williams SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST 2009 CLE CONFERENCE – WHERE TRENDY ENTERTAINMENT MEETS TRENDS IN ENTERTAINMENT LAW……………………...…………………………………………………..…186 Paul Tigan 1 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, Welcome to the Spring 2009 issue of the University of Denver Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. With this issue, we are excited to bring you insightful analysis and commentary focusing on a variety of legal topics within sports and entertainment law. Our goal is to provide compelling legal commentary on these industries, and with the hard work of our authors and editing staff, we are delighted to publish 6 articles presenting a variety of issues and perspectives. Anti-trust issues in Major League Baseball, government regulation of media content, and performance enhancing drugs in professional sports are among the topics our authors address in this edition of the Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. Additionally, a fellow law student from the University of Denver has written a review of the 2009 South-by-Southwest music and film conference. The students, professors, and practitioners of law that produce this commentary offer a valuable resource to our legal community. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

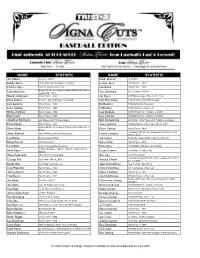

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Revisionist History and Post-Hypnotic Suggestions on the Interpretation Of

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 20 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall "Mixed Metaphors," Revisionist History and Post- Hypnotic Suggestions on the Interpretation of Sports Antitrust Exemptions: The econdS Circuit's Use in Clarett of a Piazza-like "Innovative Reinterpretation of Supreme Court Dogma" Walter T. Champion, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Walter T. Champion, Jr., "Mixed Metaphors," Revisionist History and Post-Hypnotic Suggestions on the Interpretation of Sports Antitrust Exemptions: The Second Circuit's Use in Clarett of a Piazza-like "Innovative Reinterpretation of Supreme Court Dogma", 20 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 55 (2009) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol20/iss1/3 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "MIXED METAPHORS," REVISIONIST HISTORY AND POST-HYPNOTIC SUGGESTIONS ON THE INTERPRETATION OF SPORTS ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS: THE SECOND CIRCUIT'S USE IN CLARETT OF A PIAZZA- LIKE "INNOVATIVE REINTERPRETATION OF SUPREME COURT DOGMA" BY WALTER T. CHAMPION, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court has a history of misinterpreting cases that involve sports antitrust exemptions. The most infamous antitrust exemption case of this sort is Flood v. Kuhn.I This case "was an antitrust action based on baseball's failure to allow St. Louis Cardinals' outfielder Curt Flood to negotiate his own contract with another team on the basis that 'free agency' in any form, was not permitted under the reserve system." 2 As Curt Flood said, "I should be able to negotiate for myself in an open market and see just how much money this little body is worth. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings October 27, 2017 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1998-President Bill Clinton signs the Curt Flood Act, overturning part of baseball’s 70-year-old antitrust exemption, putting baseball on par with other professional sports, when it relates to labor matters MLB.COM Four Reds named NL Gold Glove Award finalists Votto, Duvall, Hamilton, Barnhart one of 3 nominees at respective positions By Daniel Kramer / MLB.com | October 26th, 2017 + 9 COMMENTS The Reds felt they were among the best defensive teams in the National League in 2017, and on Thursday, they were given validation for that assertion. First baseman Joey Votto, left fielder Adam Duvall, center fielder Billy Hamilton and catcher Tucker Barnhart were named Rawlings NL Gold Glove Award finalists. Each player is one of three nominees at his respective position for the prestigious award that recognizes the best defensive player at each position for each league. The four nominations are an NL high for any club. The winners will be unveiled on Nov. 7 at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN. "I think we've got legitimate candidates here to win the award," Reds manager Bryan Price said. "The four guys who have been acknowledged in the final vote is really good, and I'm excited. But I would really like to see us get acknowledged beyond getting into the finalists and actually win some awards." This is the fourth straight year Hamilton has been nominated, though he has yet to win. In 2017, Hamilton converted three five-star catches, rated by Statcast™ as the most elite such outfield plays, those with a catch probability of 25 percent or less. -

8/9/17 Detroit Tigers at St Louis Cardinals Box Score

Game Stats - 7/22/17 Detroit Tigers at St Louis Cardinals Box Score DETROIT TIGERS (1) AT ST LOUIS CARDINALS (6) DETROIT TIGERS AB R H BI ST LOUIS CARDINALS AB R H BI Dick Mcauliffe 3 0 0 0 Lou Brock 3 0 1 0 Mickey Stanley 4 1 1 1 Curt Flood 3 1 0 0 Al Kaline 4 0 0 0 Roger Maris 3 1 0 0 Norm Cash 4 0 0 0 Orlando Cepeda 4 1 2 2 Willie Horton 2 0 0 0 Tim McCarver 3 1 1 1 Jim Northrup 3 0 1 0 Mike Shannon 4 1 1 1 Bill Freehan 3 0 0 0 Julian Javier 4 1 2 1 Don Wert 3 0 0 0 Dal Maxvill 4 0 0 1 Denny Mclain 1 0 0 0 Bob Gibson 4 0 0 0 Eddie Mathews 1 0 0 0 Gates Brown 1 0 0 0 TOTALS 29 1 2 1 TOTALS 32 6 7 6 DETROIT TIGERS 000 001 000 -- 1 ST LOUIS CARDINALS 200 300 10x -- 6 LOB--DETROIT TIGERS 3, ST LOUIS CARDINALS 6. ERR--Mickey Stanley, Norm Cash, Mike Shannon. 2B--Jim Northrup. 3B--Julian Javier, Mike Shannon. HR--Mickey Stanley, Orlando Cepeda. SB--Lou Brock. DETROIT TIGERS IP H R ER BB SO HR Denny Mclain (L) 5.00 5 5 5 3 7 1 Daryl Patterson 2.00 2 1 1 1 0 0 John Hiller 1.00 0 0 0 0 0 0 ST LOUIS CARDINALS Bob Gibson (W) 9.00 2 1 1 2 5 1 SO--Mickey Stanley, Dick Mcauliffe (2), Al Kaline, Bill Freehan, Roger Maris, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Mike Shannon, Orlando Cepeda, Curt Flood (2). -

Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports

Fordham Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 9 1999 Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Jason M. Pollack Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason M. Pollack, Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 1645 (1999). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Cover Page Footnote I dedicate this Note to Mom and Momma, for their love, support, and Chicken Marsala. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 TAKE MY ARBITRATOR, PLEASE: COMMISSIONER "BEST INTERESTS" DISCIPLINARY AUTHORITY IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS Jason M. Pollack* "[I]f participants and spectators alike cannot assume integrity and fairness, and proceed from there, the contest cannot in its essence exist." A. Bartlett Giamatti - 19871 INTRODUCTION During the first World War, the United States government closed the nation's horsetracks, prompting gamblers to turn their -

Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting Biotechnology In

FROM FLOOD TO FREE AGENCY: THE MESSERSMITH-MCNALLY ARBITRATION RECONSIDERED Henry D. Fetter* INTRODUCTION .............................................................................157 I. THE FLOOD CASE AND ITS AFTERMATH ...................................161 II. THE MESSERSMITH-MCNALLY ARBITRATION .......................... 165 III. PARAGRAPH 10(A) IN THE CURT FLOOD CASE ...................... 168 IV. THE AWARD ...........................................................................177 V. EXPLAINING THE AWARD ........................................................178 * Henry D. Fetter is the author of TAKING ON THE YANKEES: WINNING AND LOSING IN THE BUSINESS OF BASEBALL (2005). His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Times Literary Supplement, The Public Interest, New York History, and the Journal of Sport History and he blogs about the politics and business of sports for theatlantic.com. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School and also holds degrees in history from Harvard College and the University of California, Berkeley. He is a member of the California and New York bars and has practiced business and entertainment litigation in Los Angeles for the past thirty years. Research for this article was funded in part by a Yoseloff-SABR Research Grant from the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). I wish to thank Albany Government Law Review for the opportunity to participate in the “Baseball and the Law” symposium and Bennett Liebman, my East Meadow High School classmate, the then-executive director of the Albany Law School Government Law Center, for initiating the invitation to appear. 156 2012] FROM FLOOD TO FREE AGENCY 157 INTRODUCTION On December 23, 1975, a three-member arbitration panel chaired, by neutral arbitrator Peter Seitz, ruled by a two-to-one vote that Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and Baltimore Orioles pitcher Dave McNally were “free agents” who could negotiate with any major league club for their future services.