Revisionist History and Post-Hypnotic Suggestions on the Interpretation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 8 Article 12 Issue 2 Spring Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J. Gordon Hylton Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation J. Gordon Hylton, Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law, 8 Marq. Sports L. J. 455 (1998) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol8/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS LEGAL BASES: BASEBALL AND THE LAW Roger I. Abrams [Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Temple University Press 1998] xi / 226 pages ISBN: 1-56639-599-2 In spite of the greater popularity of football and basketball, baseball remains the sport of greatest interest to writers, artists, and historians. The same appears to be true for law professors as well. Recent years have seen the publication Spencer Waller, Neil Cohen, & Paul Finkelman's, Baseball and the American Legal Mind (1995) and G. Ed- ward White's, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1953 (1996). Now noted labor law expert and Rutgers-Newark Law School Dean Roger Abrams has entered the field with Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law. Unlike the Waller, Cohen, Finkelman anthology of documents and White's history, Abrams does not attempt the survey the full range of intersections between the baseball industry and the legal system. In- stead, he focuses upon the history of labor-management relations. -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

Instituto Laboral De La Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards

Instituto Laboral de la Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards Friday, February 18th, 2011 Reception and Media Coverage: 5:00pm Dinner and Awards: 6:30pm Hotel Marriott Marquis — San Francisco 55 Fourth Street, San Francisco, CA 2011 Honorees GUEST OF HONOR & LABOR LEADER OF THE YEAR Edwin D. Hill LA RAZA CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP AWARD Senator Barbara Boxer (US Senate, CA) LA RAZA CIVIL RIGHTS AWARD Alice A. Huffman JIM RUSH LABOR AND COMMUNITY ACTIVIST AWARD Earl “Marty” Averette LA RAZA SAN PATRICIO LEADERSHIP AWARD George Landers LA RAZA CORPORATE LEADERSHIP AWARD Josh Becker CURT FLOOD LABOR-COMMUNITY AWARD Major League Baseball Players Association Welcome Instituto Laboral de la Raza Instituto Laboral de la Raza STAFF 2947 16th STREET • SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103 SARAH M. SHAKER Dear Labor Friends and Supporters: Executive Director Welcome to the Instituto Laboral de la Raza’s 2011 National Labor-Community Awards. This evening we BRIAN E. WEBSTER honor Edwin D. Hill, International President of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, our Chief of Staff and Events Manager Guest of Honor and Labor Leader of the Year. According to the Huffington Post, President Hill “is a leading voice for a balanced and practical approach to the nation’s pursuit of energy independence“... and he expands “the role of job training … seeking to combat global warming.” DOUG HAAKE WALTER SANCHEZ Legal Aid Legal Aid and Program Manager We are very proud of our U.S. Senator, Barbara Boxer (D-CA). Senator Boxer is a true fighter for liberal causes. Senator Boxer, like the late Senator Ted Kennedy, truly cares for the rights of the working man and ROSA ARGENTINA OATES ISENIA D. -

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes Kevin McDonald 1. introduction this: It happens every spring. The perennial hopefulness of opening day leads to talk of LEVEL ONE: “Justice Holmes baseball, which these days means the business ruled that baseball was a sport, not a of baseball - dollars and contracts. And business.” whether the latest topic is a labor dispute, al- LEVEL TWO: “Justice Holmes held leged “collusion” by owners, or a franchise that personal services, like sports and considering a move to a new city, you eventu- law and medicine, were not ‘trade or ally find yourself explaining to someone - commerce’ within the meaning of the rather sheepishly - that baseball is “exempt” Sherman Act like manufacturing. That from the antitrust laws. view has been overruled by later In response to the incredulous question cases, but the exemption for baseball (“Just how did that happen?”), the customary remains.” explanation is: “Well, the famous Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. decided that baseball was exempt from the antitrust laws in a case called The truly dogged questioner points out Federal Baseball Club ofBaltimore 1.: National that Holmes retired some time ago. How can we League of Professional Baseball Clubs,‘ and have a baseball exemption now, when the an- it’s still the law.” If the questioner persists by nual salary for any pitcher who can win fifteen asking the basis for the Great Dissenter’s edict, games is approaching the Gross National Prod- the most common responses depend on one’s uct of Guam? You might then explain that the level of antitrust expertise, but usually go like issue was not raised again in the courts until JOURNAL 1998, VOL. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

FLOOD V. KUHN Supreme Court of the United States 407 U.S

FLOOD v. KUHN Supreme Court of the United States 407 U.S. 258, 92 S. Ct. 2099 (1972) Mr. Justice BLACKMUN delivered the opinion of the Court. For the third time in 50 years the Court is asked specifically to rule that professional baseball's reserve system is within the reach of the federal antitrust laws.1 . 1 The reserve system, publicly introduced into baseball contracts in 1887, see Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 F. 198, 202--204 (C.C.SDNY 1890), centers in the uniformity of player contracts; the confinement of the player to the club that has him under the contract; the assignability of the player's contract; and the ability of the club annually to renew the contract unilaterally, subject to a stated salary minimum. Thus A. Rule 3 of the Major League Rules provides in part: '(a) UNIFORM CONTRACT. To preserve morale and to produce the similarity of conditions necessary to keen competition, the contracts between all clubs and their players in the Major Leagues shall be in a single form which shall be prescribed by the Major League Executive Council. No club shall make a contract different from the uniform contract or a contract containing a non-reserve clause, except with the written approval of the Commissioner. '(g) TAMPERING. To preserve discipline and competition, and to prevent the enticement of players, coaches, managers and umpires, there shall be no negotiations or dealings respecting employment, either present or prospective, between any player, coach or manager and any club other than the club with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, or by which he is reserved, or which has the player on its Negotiation List, or between any umpire and any league other than the league with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, unless the club or league with which he is connected shall have, in writing, expressly authorized such negotiations or dealings prior to their commencement.' B. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

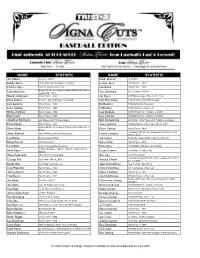

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Anatomy of an Aberration: an Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball Through Flood V

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 2 Spring 2008 Article 2 Anatomy of an Aberration: An Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball through Flood v. Kuhn (1972) David L. Snyder Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation David L. Snyder, Anatomy of an Aberration: An Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball through Flood v. Kuhn (1972), 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 177 (2008) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANATOMY OF AN ABERRATION: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ATTEMPTS TO APPLY ANTIRUST LAW TO MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL THROUGH FLOOD V. KUHN (1972) David L. Snyder* I. INTRODUCTION The notion that baseball has always been exempt from antitrust laws is a commonly accepted postulate in sports law. This historical overview traces the attempts to apply antitrust law to professional baseball from the development of antitrust law and the reserve system in baseball in the late 1800s, through the lineage of cases in the Twen- tieth Century, ending with Flood v. Kuhn in 1972.1 A thorough exam- ination of the case history suggests that baseball's so-called antitrust "exemption" actually arose from a complete misreading of the Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings October 27, 2017 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1998-President Bill Clinton signs the Curt Flood Act, overturning part of baseball’s 70-year-old antitrust exemption, putting baseball on par with other professional sports, when it relates to labor matters MLB.COM Four Reds named NL Gold Glove Award finalists Votto, Duvall, Hamilton, Barnhart one of 3 nominees at respective positions By Daniel Kramer / MLB.com | October 26th, 2017 + 9 COMMENTS The Reds felt they were among the best defensive teams in the National League in 2017, and on Thursday, they were given validation for that assertion. First baseman Joey Votto, left fielder Adam Duvall, center fielder Billy Hamilton and catcher Tucker Barnhart were named Rawlings NL Gold Glove Award finalists. Each player is one of three nominees at his respective position for the prestigious award that recognizes the best defensive player at each position for each league. The four nominations are an NL high for any club. The winners will be unveiled on Nov. 7 at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN. "I think we've got legitimate candidates here to win the award," Reds manager Bryan Price said. "The four guys who have been acknowledged in the final vote is really good, and I'm excited. But I would really like to see us get acknowledged beyond getting into the finalists and actually win some awards." This is the fourth straight year Hamilton has been nominated, though he has yet to win. In 2017, Hamilton converted three five-star catches, rated by Statcast™ as the most elite such outfield plays, those with a catch probability of 25 percent or less. -

Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption Ed Edmonds Notre Dame Law School, [email protected]

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 1994 Over Forty Years in the On-Deck Circle: Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption Ed Edmonds Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Ed Edmonds, Over Forty Years in the On-Deck Circle: Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption, 19 T. Marshall L. Rev. 627 (1993-1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/470 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OVER FORTY YEARS IN THE ON-DECK CIRCLE: CONGRESS AND THE BASEBALL ANTITRUST EXEMPTION EDMUND P. EDMONDS* In the history of the legal regulation of professional teams sports, probably the widest known and least precisely understood is the trilogy of United States Supreme Court cases' establishing Major League Baseball's exemption from federal antitrust laws 2 and the actions of the United States Congress regarding the exemption. In the wake of the ouster of Fay Vincent as the Commissioner of Baseball' and against * Director of the Law Library and Professor of Law, Loyola University School of Law, New Orleans. B.A., 1973, University of Notre Dame, M.L.S., 1974, University of Maryland, J.D., 1978, University of Toledo. I wish to thank William P.