Title VII & MLB Minority Hiring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Doc < Dominican Baseball: New Pride, Old Prejudice (Paperback)

LULND5YKH4IK \ Doc \\ Dominican Baseball: New Pride, Old Prejudice (Paperback) Dominican Baseball: New Pride, Old Prejudice (Paperback) Filesize: 1.05 MB Reviews The ideal book i actually read. It is one of the most awesome pdf i have study. I am just happy to tell you that this is basically the best book i have study in my own life and might be he finest ebook for actually. (Nettie Leuschke) DISCLAIMER | DMCA H7PVOHGFSM3H < Kindle / Dominican Baseball: New Pride, Old Prejudice (Paperback) DOMINICAN BASEBALL: NEW PRIDE, OLD PREJUDICE (PAPERBACK) Temple University Press,U.S., United States, 2014. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Pedro Martinez. Sammy Sosa. Manny Ramirez. By 2000, Dominican baseball players were in every Major League clubhouse, and regularly winning every baseball award. In 2002, Omar Minaya became the first Dominican general manager of a Major League team. But how did this codependent relationship between MLB and Dominican talent arise and thrive? In his incisive and engaging book, Dominican Baseball, Alan Klein examines the history of MLB s presence and influence in the Dominican Republic, the development of the booming industry and academies, and the dependence on Dominican player developers, known as buscones. He also addresses issues of identity fraud and the use of performance-enhancing drugs as hopefuls seek to play professionally. Dominican Baseball charts the trajectory of the economic flows of this transnational exchange, and the pride Dominicans feel in their growing influence in the sport. Klein also uncovers the prejudice that prompts MLB to diminish Dominican claims on legitimacy. This sharp, smartly argued book deftly chronicles the uneasy and often contested relations of the contemporary Dominican game and industry. -

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

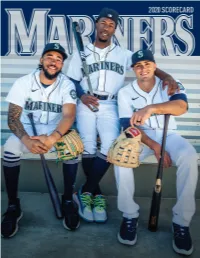

Play Ball in Style

Manager: Scott Servais (9) NUMERICAL ROSTER 2 Tom Murphy C 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 5 Jake Bauers INF 6 Perry Hill COACH 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 9 Scott Servais MANAGER 10 Jarred Kelenic OF 13 Abraham Toro INF 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 16 Drew Steckenrider RHP 17 Mitch Haniger OF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 21 Tim Laker COACH 22 Luis Torrens C 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF 27 Matt Andriese RHP 28 Jake Fraley OF 29 Cal Raleigh C 31 Tyler Anderson LHP 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 36 Logan Gilbert RHP 37 Paul Sewald RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 40 Wyatt Mills RHP 43 Joe Smith RHP 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 50 Erik Swanson RHP 55 Yohan Ramirez RHP 63 Diego Castillo RHP 66 Fleming Baez COACH 77 Chris Flexen RHP 79 Trent Blank COACH 88 Jarret DeHart COACH 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH 99 Keynan Middleton RHP SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (14) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 31 Tyler Anderson L-L 6-2 213 12/30/89 Las Vegas, NV 27 Matt Andriese R-R 6-2 215 08/28/89 Redlands, CA 63 Diego Castillo (IL) R-R 6-3 250 01/18/94 Cabrera, DR 77 Chris Flexen R-R 6-3 230 07/01/94 Newark, CA PLAY BALL IN STYLE. 36 Logan Gilbert R-R 6-6 225 05/05/97 Apopka, FL MARINERS SUITES PROVIDE THE PERFECT 7 Marco Gonzales L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 18 Yusei Kikuchi L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Morioka, Japan SETTING FOR YOUR NEXT EVENT. -

Texas Review of & Sports

Texas Review of Entertainment & Sports Law Volume 15 Fall 2013 Number 1 Finding a Solution: Getting Professional Basketball Players Paid Overseas Steven Olenick, Jenna Kochen, and Jason Sosnovsky Analyzing the United States - Japanese Player Contract Agreement: Is this Agreement in the best interest of Major League Baseball players and if not, should the MLB Players Association challenge the legality of Agreement as a violation of federal law? Robert J Romano All Quiet on the Digital Front: The NCAAs Wide Discretion in Regulating Social Media Aaron Hernandez Get with the Times: Why Defamation Law Must be Reformed in Order to Protect Athletes and Celebrities from Media Attacks Matthew T Poorman TRESL Symposium 2013 Panel Discussion: "Asking the Audience for Help: Crowdfunding as a Means of Control" September 13, 2013 - The University of Texas at Austin Published by The University of Texas School of Law Texas Review of Volume 15 Issue 1 Entertainment Fall2013 & Sports Law CONTENTS ARTICLES FINDING A SOLUTION: GETTING PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL PLAYERS PAID O V ER SEAS ....................................................................................................... 1 Steven Olenick, Jenna Kochen, and Jason Sosnovsky ANALYZING THE UNITED STATES - JAPANESE PLAYER CONTRACT AGREEMENT: IS THIS AGREEMENT IN THE BEST INTEREST OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PLAYERS AND IF NOT, SHOULD THE MLB PLAYERS ASSOCIATION CHALLENGE THE LEGALITY OF THE AGREEMENT AS A VIOLATION OF FEDERAL LAW?..... .. 19 Robert J. Romano NOTES ALL QUIET ON THE DIGITAL FRONT: THE -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

0908 Giants.Pdf

Manager: Scott Servais (29) NUMERICAL ROSTER 1 Kyle Lewis OF 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 6 Yoshihisa Hirano RHP 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 9 Dee Strange-Gordon INF/OF 12 Evan White INF 13 Perry Hill COACH 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 20 Phillip Ervin OF 21 Tim Laker COACH 22 Luis Torrens C 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF/OF 26 José Marmolejos INF 27 Joe Thurston COACH 28 Sam Haggerty INF 29 Scott Servais MANAGER 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 35 Justin Dunn RHP 37 Casey Sadler RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 40 Brian DeLunas COACH 44 Jarret DeHart COACH 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 49 Kendall Graveman RHP 50 Erik Swanson RHP 52 Nick Margevicius LHP 54 Joseph Odom C 55 Yohan Ramirez RHP 59 Joey Gerber RHP 60 Seth Frankoff RHP 62 Brady Lail RHP 65 Brandon Brennan RHP 66 Fleming Báez COACH 73 Walker Lockett RHP 74 Ljay Newsome RHP 81 Aaron Fletcher LHP 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (16) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 65 BRENNAN, Brandon (IL) R-R 6-4 220 07/26/91 Mission Viejo, CA 35 DUNN, Justin R-R 6-2 185 09/22/95 Freeport, NY 81 FLETCHER, Aaron L-L 6-0 220 02/26/96 Geneseo, IL 60 FRANKOFF, Seth R-R 6-5 215 08/27/88 Raleigh, NC 59 GERBER, Joey R-R 6-4 215 05/03/97 Maple Grove, MN 7 GONZALES, Marco L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 49 GRAVEMAN, Kendall R-R 6-2 200 12/21/90 Alexander City, AL 6 HIRANO, Yoshihisa R-R 6-1 185 03/08/84 Kyoto, Japan 18 KIKUCHI, Yusei L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Iwate, Japan 62 LAIL, Brady R-R 6-2 200 08/09/93 South Jordan, UT 73 LOCKETT, Walker R-R 6-5 225 05/03/94 Jacksonville, FL 52 MARGEVICIUS, Nick L-L 6-5 220 06/18/96 Cleveland, OH 38 MISIEWICZ, Anthony R-L 6-1 200 11/01/94 Detroit, MI 74 NEWSOME, Ljay R-R 5-11 210 11/08/96 La Plata, MD 55 RAMIREZ, Yohan R-R 6-4 190 05/06/95 Villa Mella, DR 37 SADLER, Casey R-R 6-3 205 07/13/90 Stillwater, OK 33 SHEFFIELD, Justus L-L 6-0 200 05/13/96 Tullahoma, TN 50 SWANSON, Erik (IL) R-R 6-3 220 09/04/93 Fargo, ND NO. -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

Clemente Quietly Grew in Stature by Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.Com

Clemente quietly grew in stature By Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.com "It's not just a death, it's a hero's death. A lot of athletes do wonderful things – but they don't die doing it," says former teammate Steve Blass about Roberto Clemente on ESPN Classic's SportsCentury series. Playing in an era dominated by the likes of Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente was usually overlooked by fans when they discussed great players. Not until late in his 18- year career did the public appreciate the many talents of the 12-time All-Star of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Of all Clemente's skills, his best tool was his right arm. From rightfield, he unleashed lasers. He set a record by leading the National League in assists five seasons. He probably would have led even more times, but players learned it wasn't wise to run on Clemente. Combined with his arm, his ability to track down fly balls earned him Gold Gloves the last 12 years of his career. At bat, Clemente seemed uncomfortable, rolling his neck and stretching his back. But it was the pitchers who felt the pain. Standing deep in the box, the right-handed hitter would drive the ball to all fields. After batting above .300 just once in his first five seasons, Clemente came into his own as a hitter. Starting in 1960, he batted above .311 in 12 of his final 13 seasons, and won four batting titles in a seven-year period. Clemente's legacy lives on -- look no farther than the number on Sammy Sosa's back. -

Instituto Laboral De La Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards

Instituto Laboral de la Raza 2011 National Labor-Community Awards Friday, February 18th, 2011 Reception and Media Coverage: 5:00pm Dinner and Awards: 6:30pm Hotel Marriott Marquis — San Francisco 55 Fourth Street, San Francisco, CA 2011 Honorees GUEST OF HONOR & LABOR LEADER OF THE YEAR Edwin D. Hill LA RAZA CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP AWARD Senator Barbara Boxer (US Senate, CA) LA RAZA CIVIL RIGHTS AWARD Alice A. Huffman JIM RUSH LABOR AND COMMUNITY ACTIVIST AWARD Earl “Marty” Averette LA RAZA SAN PATRICIO LEADERSHIP AWARD George Landers LA RAZA CORPORATE LEADERSHIP AWARD Josh Becker CURT FLOOD LABOR-COMMUNITY AWARD Major League Baseball Players Association Welcome Instituto Laboral de la Raza Instituto Laboral de la Raza STAFF 2947 16th STREET • SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103 SARAH M. SHAKER Dear Labor Friends and Supporters: Executive Director Welcome to the Instituto Laboral de la Raza’s 2011 National Labor-Community Awards. This evening we BRIAN E. WEBSTER honor Edwin D. Hill, International President of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, our Chief of Staff and Events Manager Guest of Honor and Labor Leader of the Year. According to the Huffington Post, President Hill “is a leading voice for a balanced and practical approach to the nation’s pursuit of energy independence“... and he expands “the role of job training … seeking to combat global warming.” DOUG HAAKE WALTER SANCHEZ Legal Aid Legal Aid and Program Manager We are very proud of our U.S. Senator, Barbara Boxer (D-CA). Senator Boxer is a true fighter for liberal causes. Senator Boxer, like the late Senator Ted Kennedy, truly cares for the rights of the working man and ROSA ARGENTINA OATES ISENIA D. -

Shir Notes the Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018

Shir Notes The Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018. Affiliated with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Rabbi’s Column Events . We’re going to dedicate a Ner Tamid at the end of this of the Month month. Shabbat services at It was designed by us but hand-made in Israel reflecting our de Toledo High School name and the congregation’s musical emphasis. I’d post a picture, but we Saturday, June `9 - 10:30 am Birthday Shabbat want the reveal on June 23 to be our first view of this artistic endeavor! Saturday, June 23 - 10:30 am The Eternal Light is often associated with the menorah, the seven-branched Anniversary Shabbat lamp stand which was part of the Bet HaMikdash – the Holy Temple in Ner Tamid dedication Jerusalem. (See article on page 2) Kiddush lunch for Ethyl Granik’s The rabbis interpreted the Ner Tamid as a symbol of God’s eternal presence 90th birthday in the world. --------------------------------------------- Walk Around Lake Balboa Originally the Ner Tamid was an oil lamp. Ours will be a battery powered Sunday, June 3, 9:00 am bulb. It’s supposed to be “eternal” but how long the batteries last will determine that. Our Walk this year raises money for the Painted Turtle Camp for Obviously, we have been able to manage without a Ner Tamid this long, so seriously ill children. Call Sheilah what will this light add to our lives? Hart at (818) 884-2342. See article on page 4 and flyer. The light shines above the ark, repository of the Torah scrolls. -

Pronk's Homer Punctuates Sweep of Royals by Robert Falkoff / Special

Pronk's homer punctuates sweep of Royals By Robert Falkoff / Special to MLB.com | 4/15/2012 8:20 PM ET KANSAS CITY -- The Indians made a statement with their offense over the weekend and Travis Hafner delivered the symbolic exclamation point. In Cleveland's 13-7 victory over the Royals on Sunday, Hafner launched the most majestic of his team's four homers. Hafner's 456-foot blast to right field in the fifth inning off Luis Mendoza traveled so far that it wound up as a souvenir inside Rivals Sports Bar, which is located high above the wall. No word on whether it came down in somebody's order of chicken wings. It was the first homer to land in the Rivals establishment since Kauffman Stadium was renovated in 2009. In short, Hafner got all of it and then some. "I was able to stay back on an off-speed pitch and backspin it," said Hafner, who finished 3-for-4. "I think there have been some [homers] before that measured in the 470s, but that's about as good as I can hit 'em." Shelley Duncan, Casey Kotchman and Jason Kipnis joined Hafner in the home run parade, as the Indians put up runs in bunches and applied the finishing touches on a three-game sweep. Right-hander Ubaldo Jimenez, making his return from a five-game suspension, labored through five innings, but got the win thanks to robust offensive support. "The first three innings, it was hard to get in a good rhythm," said Jimenez, who refused to use rustiness as an excuse.