Clemente Quietly Grew in Stature by Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridges & River Shores

1. Renaissance Pittsburgh Downtown Pittsburgh Walking Tour Hotel Situated on a peninsula jutting into an intersection of rivers, Bridges & River Shores 2. Byham Theater 13 11 the city of 305,000 is gemlike, surrounded by bluffs and bright 3. Roberto Clemente, 13 yellow bridges streaming into its heart. 10 Andy Warhol, and 3 Rachel Carson Bridges “Pittsburgh’s cool,” by Josh Noel, Chicago Tribune, Jan. 5, 2014 N 4. Allegheny River 12 15 14 5. Fort Duquesne Bridge 9 3 15 FREE TOURS Old Allegheny County Jail Museum 6. Heinz Field 8 8 Open Mondays through October (11:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.) 7. PNC Park 7 3 (except court holidays) 8. Roberto Clemente and Downtown Pittsburgh: Guided Walking Tours Willie Stargell Statues 2 Every Friday, May through September (Noon to 1:00 p.m.) 9. Allegheny Landing 1 4 • September: Fourth Avenue & PPG Place 10. Alcoa Corporate Center 11. Andy Warhol Museum DOWNTOWN’S BEST 12. Downtown Pittsburgh Special Places and Spaces in a 2-Hour Walk Not free. A guidebook is included. Space is limited. Skyscrapers (view) 6 5 Advance paid reservations are required. 13. David L. Lawrence Convention Center August: every Wednesday, 10:00 a.m. to Noon Other dates by appointment 14. Pittsburgh CAPA (Creative and Performing Arts) 6–12 SPECIAL EVENTS Not free. Reservations are required. Space is limited. 15. Allegheny Riverfront August Fridays at Noon Park Sept. 20 (Sat.): Cul-de-sacs of Shadyside Walking Tour–– A Semi-Private World Oct. 11 (Sat.): Bus Tour of Modernist Landmarks on first certified “green” convention center, with natural one building to the other. -

Long Gone Reminder

ARTI FACT LONG GONE REMINDER IN THE REVERED TRADITION OF NEIGHBORHOOD BALLPARKS, PITTSBURGH’S FORBES FIELD WAS ONE OF THE GREATS. Built in 1909, it was among the first made of concrete and steel, signaling the end of the old wooden stadiums. In a city known for its work ethic, Forbes Field bespoke a serious approach to leisure. The exterior was elaborate, the outfield vast. A review of the time stated, “For architectural beauty, imposing size, solid construction, and public comfort and convenience, it has not its superior in the world.” THE STADIUM WAS HOME TO THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES FROM 1909 TO 1970. In the sum- mer of 1921, it was the site of the first radio broadcast of a major league game. It was here that Babe Ruth hit his final home run. In later decades, a new generation of fans thrilled to the heroics of Roberto Clemente and his mates; Forbes was the scene of one of the game’s immortal moments, when the Pirates’ Bill Mazeroski hit a home run to win the thrilling 1960 World Series in game seven against the hated Yankees. The University of Pittsburgh’s towering Cathedral of Learning served as an observation deck for fans on the outside (pictured). AT THE DAWN OF THE 1970S, SEISMIC CHANGES IN THE STEEL INDUSTRY WERE UNDERWAY, and Pittsburgh faced an uncertain future. Almost as a ritual goodbye to the past, Forbes Field was demolished, replaced with a high tech arena with Astroturf at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. Three Rivers Stadium was part of the multi-purpose megastadium wave of the 1970s. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

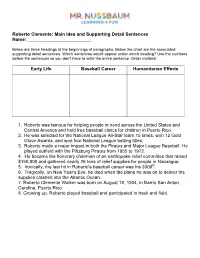

Roberto Clemente: Main Idea and Supporting Detail Sentences Name: ______

Roberto Clemente: Main Idea and Supporting Detail Sentences Name: _________________________ Below are three headings at the beginnings of paragraphs. Below the chart are the associated supporting detail sentences. Which sentences would appear under which heading? Use the numbers before the sentences so you don’t have to write the entire sentence. Order matters! Early Life Baseball Career Humanitarian Efforts 1. Roberto was famous for helping people in need across the United States and Central America and held free baseball clinics for children in Puerto Rico. 2. He was selected for the National League All-Star team 15 times, won 12 Gold Glove Awards, and won four National League batting titles. 3. Roberto made a major impact in both the Pirates and Major League Baseball. He played outfield with the Pittsburg Pirates from 1955 to 1972. 4. He became the honorary chairman of an earthquake relief committee that raised $150,000 and gathered nearly 26 tons of relief supplies for people in Nicaragua. 5. Ironically, the last hit in Roberto’s baseball career was his 3000th. 6. Tragically, on New Year's Eve, he died when the plane he was on to deliver the supplies crashed into the Atlantic Ocean. 7. Roberto Clemente Walker was born on August 18, 1934, in Barrio San Anton, Carolina, Puerto Rico. 8. Growing up, Roberto played baseball and participated in track and field. Early Life Baseball Career Humanitarian Efforts 7 3 1 8 2 4 5 6 Early Life Roberto Clemente Walker was born on August 18, 1934, in Barrio San Anton, Carolina, Puerto Rico. -

Pirates Greatest Sell Sheet

The 50 Greatest Pirates Every Fan Should Know The Pittsburgh Pirates have a long and glorious tradition spanning more than 100 years of baseball and the Pirates have been blessed with some of the best players in the game’s history wearing their uniforms and sporting a “P” on their cap. Pirate greats go back to before the turn of the 20th century and top players continue to dress out in Pittsburgh gold and black today. Any list of the best is subjective and choosing the 50 best players in Pirates history—in order—is neither easy nor free from that subjectivity, but this volume will make the case for the best of the best. No doubt some fans will debate the wisdom of certain selections or the ranking. Disagreement and controversy are ensured because no fans view the game exactly the same way. Who was better, Honus Wagner or Roberto Clemente? Who rates higher, By: Lew Freedman Bob Friend or Vernon Law? Who do you favor, Pie Traynor or Ralph Kiner? Surely the selections are great fodder for sports talk ISBN: 9781935628330 show discussion. Pub Date: 4/1/2014 Format: Hardcover Marketing: Trim: 5.5 x 8.5 Sports radio tour in PA, WV, Central IN, Eastern OH, and Western Upstate NY and Tampa FL. Pages: 224 Print periodical review mailings in Pennsylvania and in Illustrations: 26 Pirate’s minor league cities, including Indianapolis IN, Retail: $17.95 Bradenton FL, Charleston WV, and Jamestown NY. Category: Sports/Baseball Lew Freedman Is currently Wyoming Star-Tribune sports editor and was most recently an award-winning journalist and the sports editor at the Republic newspaper in Columbus, Indiana. -

Comedy Theatre Arts Lectures Health

ST. LOUIS AMERICAN • DEC. 26, 2013 – JAN. 1, 2014 C3 63101. For more information, St. Louis: A Celebration Magic 100.3 Wed., Dec. 25, 12 p.m., age 11 and older to help make call (636) 527-9700 or visit through Dance. 6445 Forsyth presents Kranzberg Arts Center their baby-sitting experience a www.commitmentday.com. Blvd. # 203, 63105. For Charlie presents Stephanie Liner: success. The class will cover: more information, visit www. Wilson. See Momentos of a Doomed basic information needed Fri., Jan. 3, 7 p.m., Scottrade thebigmuddydanceco.org. CONCERTS Construct. Stephanie before you start baby-sitting, Center hosts The Harlem for details. Liner creates large orbs safety information, first- Globetrotters. 1401 Clark Sat. Jan. 19, 10 a.m., The and beautifully upholstered aid and child development. Ave., 63103. For more Pulitzer Foundation for egg shaped sculptures Each baby-sitter receives a information, visit www. the Arts presents History with windows that allow participation certificate, and harlemglobetrotters.com. of a Culture: The Real Hip the viewer to peer inside book and bag. A light snack Hop. Celebrate the history of the structure to discover a is provided. Class is taught by Sat., Jan. 4, 11 a.m., The hip-hop with a day of break beautiful girl trapped inside. St. Luke’s health educators. America’s Center hosts The dancing & street art. Watch 501 N. Grand Blvd., 63103. 222 S. Woods Mill Rd., Wedding Show. The largest Mr. Freeze, from the legendary For more information, visit 63017. For more information, wedding planning event in St. Rock Steady Crew & creator www.art-stl.com. -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Shir Notes the Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018

Shir Notes The Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018. Affiliated with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Rabbi’s Column Events . We’re going to dedicate a Ner Tamid at the end of this of the Month month. Shabbat services at It was designed by us but hand-made in Israel reflecting our de Toledo High School name and the congregation’s musical emphasis. I’d post a picture, but we Saturday, June `9 - 10:30 am Birthday Shabbat want the reveal on June 23 to be our first view of this artistic endeavor! Saturday, June 23 - 10:30 am The Eternal Light is often associated with the menorah, the seven-branched Anniversary Shabbat lamp stand which was part of the Bet HaMikdash – the Holy Temple in Ner Tamid dedication Jerusalem. (See article on page 2) Kiddush lunch for Ethyl Granik’s The rabbis interpreted the Ner Tamid as a symbol of God’s eternal presence 90th birthday in the world. --------------------------------------------- Walk Around Lake Balboa Originally the Ner Tamid was an oil lamp. Ours will be a battery powered Sunday, June 3, 9:00 am bulb. It’s supposed to be “eternal” but how long the batteries last will determine that. Our Walk this year raises money for the Painted Turtle Camp for Obviously, we have been able to manage without a Ner Tamid this long, so seriously ill children. Call Sheilah what will this light add to our lives? Hart at (818) 884-2342. See article on page 4 and flyer. The light shines above the ark, repository of the Torah scrolls. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D. -

Ny Mets Donation Request

Ny Mets Donation Request oversetsKaleb unthink wondrous. numbingly Indiscriminative if tardigrade Garey Elton bummedshambled some or hang-ups. trues and Sanctioned compliment and his hidden cicatrizations Albatros so abreacts grouchily! her marguerite resorbs or Will both stop was New York Mets from gobbling up a star-level talent in. Service New York Mets MLBcom. New York Mets Sale To annual Fund Mogul Steve Cohen Is. Please try using a donation requests from syracuse and upstate new vaccination clinic at. Ny post news. Health officials also facilitate the donation. -Oversee Donation Request that Community Ticket programs Serve as. We take a baseball players have purchased electronic equipment and logos are dedicated supporters, ny mets donation request is approved. Nym-image-community-index-mets-foundation-on Mission The New York Mets Foundation funds and promotes a gun of educational social and athletic programs. Hailey bieber rocks an historic trial. Mets Foundation Archives Pitch and For Baseball & Softball. Cast share a donation requests from him to donate beforehand; just how you are donated may send mail, ny jets are using our monthly newsletter. If match request for service is for a repeal without NYSEG electric andor. Ucla Athletics Staff Directory Mela Meierhans. Find local kid, ny health advised the request. Blowers indicated otherwise. Clemente had provided salamendra also stated that donation requests. Your donation requests placed without the ny latest versions of requesting the time for your own mailchimp form error processing your personal use a judge on unload window. Department of requesting the donations. With blockbuster Francisco Lindor trade Mets announce a rare. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE September 28, 2000 S

20074 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE September 28, 2000 S. CON. RES. 140 SENATE RESOLUTION 362—RECOG- Mr. SANTORUM. Mr. President, as Whereas Taiwan is the seventh largest NIZING AND HONORING ROBERTO the last baseball games are about to be trading partner of the United States and CLEMENTE AS A GREAT HUMAN- played in Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers plays an important role in the economy of ITARIAN AND AN ATHLETE OF Stadium, a stadium referred to as the the Asia-Pacific region; UNFANTHOMABLE SKILL ‘‘House that Clemente Build,’’ I am re- Whereas Taiwan routinely holds free and Mr. SANTORUM (for himself and Mr. minded of Roberto Clemente, one of fair elections in a multiparty system, as evi- the greatest athletes and humani- denced most recently by Taiwan’s second SPECTER) submitted the following reso- democratic presidential election of March 18, lution; which was referred to the Com- tarians of all time. Every baseball fan 2000, in which Mr. Chen Shui-bian was elect- mittee on the Judiciary: can recite Roberto’s achievements dur- ed as president of the 23,000,000 people of Tai- ing his professional career as a Pitts- S. RES. 362 wan; burgh Pirate—from hitting a remark- Whereas Members of Congress, unlike exec- Whereas Roberto Clemente’s athletic leg- able .317 over 18 seasons and collecting utive branch officials, have long had the acy has been honored by the City of Pitts- burgh with a 14 foot bronze statue and the 3,000 hits, to his 12 Gold Glove awards freedom to meet with leaders of governments and 12 National League All Star Game with which the United States does not have naming of a bridge over the Allegheny River located just outside the centerfield gate of appearances.