Baseball Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

The BG News August 25, 1989

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 8-25-1989 The BG News August 25, 1989 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News August 25, 1989" (1989). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4959. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4959 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Friday Weather Vol.72 Issue 4 High 75° August 25, 1989 Low 55° Bowling Green, Ohio The BG News BRIEFLY 'Every Rose has its thorn' Nation Cinci'sclub Kiddie credit: The Young manager gets Americans Bank in Denver will issue its first MasterCards to children 12 years old and over this week. Children lifetime ban must have a co-signer and are allotted a $100 credit limit. The bank said it is NEW YORK (AP) - Pete Rose, trying to teach young adults proper baseball's all-time hit leader and hol- use of their personal finances for later der of 19 major-league records, was years. banned for life today for betting on his own team and other actions that had "stained the game." America alone: A new study Under the rules of baseball, Rose can concluded that in the 21st century, appeal for reinstatement after one more of our nation's elderly will be year. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

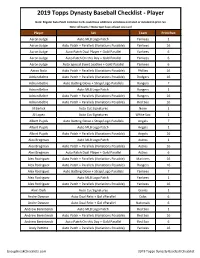

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

November 07 Retirees Newsletter

November 2007 Issue 3 Academic Year 2007-2008 Retirees Newsletter PROFESSIONAL STAFF CONGRESS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT: I thank Jim Perlstein for this colorful summary of Mr. Marvin Miller’s remarks. BALLPLAYERS AND UNIONISM: the standard player contract had MARVIN MILLER’S TALK amounted to serfdom. RESONATES WITH CUNY RETIREES Though young and inexperienced with unions, Miller found major Marvin Miller, retired leaguers to be fast learners Executive Director of the who quickly came to appreciate Major League’s Baseball their collective power through Players’ Association, collective action. The relatively provided the November small number of ballplayers meeting of the Retirees who make it to the major Chapter with a compelling leagues made it possible to retrospective on the origin and have regular one-on-one progress of baseball unionism since meetings with each player, in the 1960’s. addition to annual group meetings with each team during spring While some PSCers had looked training. And the union maintained forward to a nostalgic afternoon - an open door policy at its New York “Robin Roberts…I remember Robin headquarters so that players could Roberts” - Miller would have none of drop in during the season as their it. He kept his talk and his teams cycled through the city for responses to the numerous scheduled games. All of this, Miller questions focused on the nature of said, speeded the education unionism, particularly the question of process, kept members engaged unionism among celebrities and provided Miller and his small conditioned to see themselves as staff with the opportunity to hammer privileged independent contractors. home the idea that the members are And he stressed that ballplayers’ the union. -

Designated Hitters and Subesquent Team Scoring

DESIGNATED HITTERS AND SUBESQUENT TEAM SCORING PERFORMANCE IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE BY SARAH E. CHO DR. HOLMES FINCH – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2020 2 ABSTRACT RESEARCH PAPER: Designated Hitters and Subsequent Team Scoring Performance in Major League Baseball STUDENT: Sarah E. Cho DEGREE: Master of Science COLLEGE: Teachers College DATE: July 2020 PAGES: 27 The Designated Hitter (DH) rule in Major League Baseball (MLB) is a topic of great debate. In the National League (NL), all players take a turn at bat. However, in the American League (AL), a DH usually bats for the pitcher. MLB pitchers typically do not have strong batting averages. The DH rule was created to increase a team’s offense. This study looked at whether there is an apparent difference between the AL and the NL. In theory, a DH will lead to more hits, more runs, and therefore a higher scoring game. This study looked at the average runs per game and total home runs for the AL and NL during the 1998 through 2018 regular seasons. Since the assumptions of parametric multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were not met, a nonparametric analysis was used. The permutation test for multivariate means results showed an apparent difference between the two leagues (p < .05). A quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) was used as a follow up test and showed home runs as the variable driving the difference between the two leagues. Therefore, the AL has better scoring performance than the NL. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

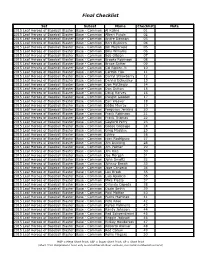

Final Checklist

Final Checklist Set Subset Name Checklist Note 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Al Kaline 01 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Albert Pujols 02 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Andre Dawson 03 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bert Blyleven 04 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bill Mazeroski 05 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Billy Williams 06 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bob Gibson 07 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Brooks Robinson 08 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bruce Sutter 09 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Cal Ripken Jr. 10 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Carlton Fisk 11 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Darryl Strawberry 12 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dennis Eckersley 13 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Mattingly 14 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Sutton 15 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Doug Harvey 16 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dwight Gooden 17 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Earl Weaver 18 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Eddie Murray 19 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Ferguson Jenkins 20 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Robinson 21 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Thomas 22 2015 Leaf Heroes of -

Chicago Tribune: Baseball World Lauds Jerome

Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman -- chicagotribune.com Page 1 of 3 www.chicagotribune.com/sports/chi-22-holtzman-baseballjul22,0,5941045.story chicagotribune.com Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman Ex-players, managers, officials laud Holtzman By Dave van Dyck Chicago Tribune reporter July 22, 2008 Chicago lost its most celebrated chronicler of the national pastime with the passing of Jerome Holtzman, and all of baseball lost an icon who so graciously linked its generations. Holtzman, the former Tribune and Sun-Times writer and later MLB's official historian, indeed belonged to the entire baseball world. He seemed to know everyone in the game while simultaneously knowing everything about the game. Praise poured in from around the country for the Hall of Famer, from management and union, managers and players. "Those of us who knew him and worked with him will always remember his good humor, his fairness and his love for baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said. "He was a very good friend of mine throughout my career in the game and I will miss his friendship and counsel. I extend my deepest sympathies to his wife, Marilyn, to his children and to his many friends." The men who sat across from Selig during labor negotiations—a fairly new wrinkle in the game that Holtzman became an expert at covering—remembered him just as fondly. "I saw Jerry at Cooperstown a few years ago and we talked old times well into the night," said Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Players Association. "We always had a good relationship. He was a careful writer and, covering a subject matter he was not familiar with, he did a remarkably good job." "You don't develop the reputation he had by accident," said present-day union boss Donald Fehr. -

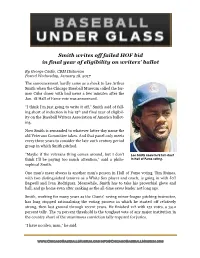

Smith Writes Off Failed HOF Bid in Final Year of Eligibility on Ballot

Smith writes off failed HOF bid in final year of eligibility on writers’ ballot By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Wednesday, January 18, 2017 The announcement hardly came as a shock to Lee Arthur Smith when the Chicago Baseball Museum called the for- mer Cubs closer with bad news a few minutes after the Jan. 18 Hall of Fame vote was announced. “I think I’m just going to write it off,” Smith said of fall- ing short of induction in his 15th and final year of eligibil- ity on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot- ing. Now Smith is remanded to whatever latter-day name the old Veterans Committee takes. And that panel only meets every three years to consider the late 20th century period group in which Smith pitched. “Maybe if the veterans thing comes around, but I don’t Lee Smith knew he'd fall short think I’ll be paying too much attention,” said a philo- in Hall of Fame voting. sophical Smith. One man’s meat always is another man’s poison in Hall of Fame voting. Tim Raines, with two distinguished tenures as a White Sox player and coach, is going in with Jeff Bagwell and Ivan Rodriguez. Meanwhile, Smith has to take his proverbial glove and ball, and go home even after ranking as the all-time saves leader not long ago. Smith, working for many years as the Giants’ roving minor-league pitching instructor, has long stopped rationalizing the voting process in which he started off relatively strong, then lost ground through recent years.