Its Effects on America's Pastime and Other Professional Sports Leagues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

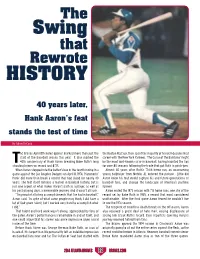

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

San Francisco Giants Weekly Notes: April 13-19

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS WEEKLY NOTES: APRIL 13-19 Oracle Park 24 Willie Mays Plaza San Francisco, CA 94107 Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com sfgigantes.com giantspressbox.com @SFGiants @SFGigantes @SFGiantsMedia NEWS & NOTES RADIO & TV THIS WEEK The Giants have created sfgiants.com/ Last Friday, Sony and the MLBPA launched fans/resource-center as a destination for MLB The Show Players League, a 30-player updates regarding the 2020 baseball sea- eSports league that will run for approxi- son as well as a place to find resources that mately three weeks. OF Hunter Pence will Monday - April 13 are being offered throughout our commu- represent the Giants. For more info, see nities during this difficult time. page two . 7:35 a.m. - Mike Krukow Fans interested in the weekly re-broadcast After crowning a fan-favorite Giant from joins Murph & Mac of classic Giants games can find a schedule the 1990-2009 era, IF Brandon Crawford 5 p.m. - Gabe Kapler for upcoming broadcasts at sfgiants.com/ has turned his sights to finding out which joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks fans/broadcasts cereal is the best. See which cereal won Tuesday - April 14 his CerealWars bracket 7:35 a.m. - Duane Kuiper joins Murph & Mac THIS WEEK IN GIANTS HISTORY 4:30 p.m. - Dave Flemming joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks APR OF Barry Bonds hit APR On Opening Day at APR Two of the NL’s top his 661st home run, the Polo Grounds, pitchers battled it Wednesday - April 15 13 passing Willie Mays 16 Mel Ott hit his 511th 18 out in San Francis- 7:35 a.m. -

Kansas City Royals

Kansas City Royals OFFICIAL GAME NOTES Los Angeles Angels (11-3) @ Kansas City Royals (3-8) Kauffman Stadium - Friday the 13th, 2018 Game #12 - Home Game #7 FOX Sports Kansas City, FOX Sports Go and KCSP Radio (610 Sports) UPCOMING PITCHING PROBABLES Saturday, April 14 vs. Los Angeles Angels: RHP Garrett Richards (1-0, 4.20) vs. RHP Jakob Junis (2-0, 0.00), 6:15 p.m., FS 1 (HD) & 610 Sports Sunday, April 15 vs. Los Angeles Angels: RHP Shohei Ohtani (2-0, 2.08) vs. LHP Eric Skoglund (0-1, 9.64), 1:15 p.m., FSKC (HD), FS 1 & 610 Sports Monday, April 16 @ Toronto Blue Jays: LHP Danny Duffy (0-2, 5.40) vs. TBA, 6:07 p.m. (CDT), FSKC (HD) & 610 Sports Tuesday, April 17 @ Toronto Blue Jays: RHP Ian Kennedy (1-1, 1.00) vs. TBA, 6:07 p.m. (CDT), FSKC (HD) & 610 Sports Wednesday, April 18 @ Toronto Blue Jays: RHP Jason Hammel (0-1+ tonight) vs. TBA, 3:07 p.m. (CDT), Facebook Live & 610 Sports Tonight’s game is being broadcast in Kansas City on KCSP Radio (610 Sports) and the Royals Radio Network with Royals’ Hall of Famer Denny Matthews, Steve Physioc and Steve Stewart...tonight is being televised on FOX Sports Kansas City and FOX Sports Go with Ryan Lefebvre and Rex Hudler calling the action...Joel Goldberg and Royals’ Hall of Famer Jeff Montgomery anchor the pre and post-game shows, Royals Live. Angels vs. Royals LATE RUNS SPOIL PITCHERS DUEL--The Royals and Angels were locked up in a tight contest, with Last night’s loss to the Halos matched the total number of de- the visitors holding a 1-0 lead entering the seventh, but Los Angeles put up a five-spot in that frame and feats the Royals incurred during the ‘17 season vs. -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Bridgeportsandmohawks Ofmeriden Clash Here Sunday

Pae Four THE BRIDGEPORT TIMES Saturday, Oct: 15, 1921 rts And Mohawks OfMeriden Clash Here Bridgepo- Sunday OUTDOOR SPORTS HERE'S A SHOCK! By Tad Football 1 LOCAL BALL CLUB ow ONLY BROKE EVEN Sport By GEORGE E. FIRSTBROOK. Monarch Although the past admissions to Nwfleld Park totaled between 80.000 ANDERSON PLEASED and 90,000 in the 1921 baseball sea- son, an increase over last season, I RGES WEIGHT LIMIT there were no mountain high profits OVER VICTORY OF according to Clark Lane, Jr., presi- FOR FOOTBALL ELEVENS dent of the Bridgeport Baseball club. 3"he guessing slats of fans who have D, H. S. RUNNERS New Haven, Oct. 13 John Heis-ma- n, been estimating the profits of the lo-c- the University of Pennsylvania club all the from $10,000 to coach and formerly of Georgia way came In The 520.000 have been badly shattered, CHICK CREATON. Tech, out today Yale according to Mr. Lane's dope. By Daily Xews favoring decision of "We managed to break about even Minus the services of six members ffkvthsll plrvon in three lnsses . and' are well satisfied," said Mr. Lane of its regular squad, through ineligi- Iieavywe-ights- middleweights and ( yesterday. bility, the Bridgeport High School Hill lightweights. The weights at which ' Albany Jumps Expensive. and Dale team easily won over the he would make the classification 'Mr. Lane explained that while the Bristol High Run yesterday afternoon are 165. 155 and 145 pounds. He ' were ex- by a score of 23-3- 2. stated that he felt that many of the htae crowds good the heavy n-n- panse involved in theMbng jumps, Matty Skane. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

"Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2000 "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O. Regalado California State University, Stanislaus Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Regalado, Samuel O. (2000) ""Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition SAMUEL 0. REGALADO ° INTRODUCTION "Bonuses? Big money promises? Uh-uh. Cambria's carrot was the fame and glory that would come from playing bisbol in the big leagues," wrote Ray Fitzgerald, reflecting on Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria's tactics in recruiting Latino baseball talent from the mid-1930s through the 1950s.' Cambria was the first of many scouts who searched Latin America for inexpensive recruits for their respective ball clubs. -

American Hercules: the Creation of Babe Ruth As an American Icon

1 American Hercules: The Creation of Babe Ruth as an American Icon David Leister TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas May 10, 2018 H.W. Brands, P.h.D Department of History Supervising Professor Michael Cramer, P.h.D. Department of Advertising and Public Relations Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….Page 5 The Dark Ages…………………………………………………………………………..…..Page 7 Ruth Before New York…………………………………………………………………….Page 12 New York 1920………………………………………………………………………….…Page 18 Ruth Arrives………………………………………………………………………………..Page 23 The Making of a Legend…………………………………………………………………...Page 27 Myth Making…………………………………………………………………………….…Page 39 Ruth’s Legacy………………………………………………………………………...……Page 46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 57 Exhibits…………………………………………………………………………………….Page 58 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….Page 65 About the Author……………………………………………………………………..……Page 68 3 “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” -The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can” -Babe Ruth 4 Abstract Like no other athlete before or since, Babe Ruth’s popularity has endured long after his playing days ended. His name has entered the popular lexicon, where “Ruthian” is a synonym for a superhuman feat, and other greats are referred to as the “Babe Ruth” of their field. Ruth’s name has even been attached to modern players, such as Shohei Ohtani, the Angels rookie known as the “Japanese Babe Ruth”. Ruth’s on field records and off-field antics have entered the realm of legend, and as a result, Ruth is often looked at as a sort of folk-hero. This thesis explains why Ruth is seen this way, and what forces led to the creation of the mythic figure surrounding the man. -

A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Summer 2007: Symposium - Regulation of Coaches' and Athletes' Behavior and Related Article 3 Contemporary Considerations A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises Jon Berkon Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Jon Berkon, A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises, 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 9 (2007) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GIANT WHIFF: WHY THE NEW CBA FAILS BASEBALL'S SMARTEST SMALL MARKET FRANCHISES INTRODUCTION Just before Game 3 of the World Series, viewers saw something en- tirely unexpected. No, it wasn't the sight of the Cardinals and Tigers playing baseball in late October. Instead, it was Commissioner Bud Selig and Donald Fehr, the head of Major League Baseball Players' Association (MLBPA), gleefully announcing a new Collective Bar- gaining Agreement (CBA), thereby guaranteeing labor peace through 2011.1 The deal was struck a full two months before the 2002 CBA had expired, an occurrence once thought as likely as George Bush and Nancy Pelosi campaigning for each other in an election year.2 Baseball insiders attributed the deal to the sport's economic health.