The Representation-‐Production of Blacks on COPS Devin Pinkney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

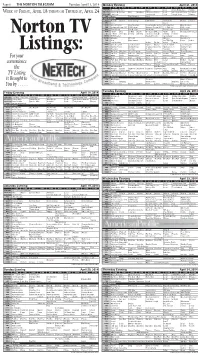

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: an Evidence-Based Proposal

Volume 65 Issue 3 Villanova Law Review Article 3 10-7-2020 Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Evidence-Based Proposal Mitch Zamoff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Mitch Zamoff, Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: Anvidence-Based E Proposal, 65 Vill. L. Rev. 585 (2020). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Zamoff: Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Ev 2020] DETERMINING THE PERSPECTIVE OF A REASONABLE POLICE OFFICER: AN EVIDENCE-BASED PROPOSAL MITCH ZAMOFF* ABSTRACT Excessive force jurisprudence in America is in disarray. Although the Supreme Court mandated over thirty years ago that courts determine the constitutionality of allegedly excessive force from the perspective of a rea- sonable officer on the scene, courts have never seemed more confused about how to make that determination. Without any definitive guidance on what evidence to consider in determining how a reasonable officer on the scene of an incident of allegedly excessive force would have behaved, courts are issuing haphazard, inconsistent decisions that are often difficult to reconcile -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Paramount Collection

Paramount Collection Airtight To control the air is to rule the world. Nuclear testing has fractured the Earth's crust, releasing poisonous gases into the atmosphere. Breathable air is now an expensive and rare commodity. A few cities have survived by constructing colossal air stacks which reach through the toxic layer to the remaining pocket of precious air above. The air is pumped into a huge underground labyrinth system, where a series of pipes to the surface feed the neighborhoods of the sealed city. It is the Air Force, known as the "tunnel hunters", that polices the system. Professor Randolph Escher has made a breakthrough in a top-secret project, the extraction of oxygen from salt water in quantity enough to return breathable air to the world. Escher is kidnapped by business tycoon Ed Conrad, who hopes to monopolize the secret process and make a fortune selling the air by subscription to the masses. Because Conrad Industries controls the air stacks, not subscribing to his "air service" would mean certain death. When Air Force Team Leader Flyer Lucci is murdered, his son Rat Lucci soon uncovers Conrad's involvement in his father's death and in Escher's kidnapping. Rat must go after Conrad, not only to avenge his father's murder, but to rescue Escher and his secret process as well. The loyalties of Rat's Air Force colleagues are questionable, but Rat has no choice. Alone, if necessary, he must fight for humanity's right to breathe. Title Airtight Genre Action Category TV Movie Format two hours Starring Grayson McCouch, Andrew Farlane, Tasma Walton Directed by Ian Barry Produced by Produced by Airtight Productions Proprietary Ltd. -

Impact of Bearing Vibration on Yarn Quality in Ring Frame

IOSR Journal of Polymer and Textile Engineering (IOSR-JPTE) e-ISSN: 2348-019X, p-ISSN: 2348-0181, Volume 2, Issue 3 (May - Jun. 2015), PP 50-59 www.iosrjournals.org Impact of Bearing Vibration on yarn quality in Ring Frame S Sundaresan*, Dr.M.Dhinakaran**, Arunraj Arumugam*** *Assistant professor (SRG), **Associate Professor (SRG), *** Assistant professor, Department of Textile Technology, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore -641049, Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract: This digital generation makes everything vibrates in the world, some vibrations are good and useful and the rest fall under the dangerous category. In spinning industry, the impact of vibration is affecting the quality of yarn. The vibration of the tin roller shaft is measured in ring spinning machine LR G5/1 equipped with 1008 spindles. The vibration of the tin roller shaft is measured in various position of the machine (near gear end, middle portion of the machine and from the off end of the machine). The vibration of the bearing also noted with respect to the cop position ( ¼ stage, ½ stage and ¾ stage). With the help of accelerometer which consists of piezoelectric sensor used to measure the vibration and to measure the acceleration of the frequency spectrum. This sensor is placed on the bearing with the help of magnetic attachment to analyse the vibration by using FFT analyser. [1]. Introduction In modern days the ring spinning operates at the maximum speed up to 25000 rpm. The ring frame also consists of 1008 to 1220 spindles per machine. The effect of tin roller bearing vibration on yarn quality can be studied by measuring the vibration of tin roller shaft bearing at different points during the running condition. -

06 SM 3/1 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 1, 2005 Monday Evening March 7, 2005 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Extreme Makeover Ho Boss Swap SuperNanny Local Local Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Listen Up Raymond 2 1/2 Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor The Contender Local Tonight Show Conan FOX American Idol 24 Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Airline Gotti Gotti Caesars 24/7 Crossing Jordan Airline AMC Rocky 2 Rocky 2 ANIM Pet Star Who Get's The Dog Animal Cops - San Fr Pet Star Who Get's The Dog CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King Norton TV DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS Love is in the Heir Howard Stern SNL ESPN Championship Week Championship Week ESPN2 Championship Week Fastbreak Streetball FAM Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Sleeping With The Enemy Fear Factor Sleeping With The Enemy HGTV Homes Ac Dec Cents Kit Trends To Sell Desg Fina Dsgnr Fin Dime D Travis Homes Ac Dec Cents HIST UFO Files Digging For The Truth Deep Sea Detectives Investigating History UFO Files LIFE Determination of Death Lies My Mother Told How Clea How Clea Nanny Golden MTV RW/RR Room Raiders Wanna? Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate SG-1 Battlestar Galactica Inferno SPIKE CSI WWE Raw WWE Raw -

The Best of Broadway

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 3, 2017 3:17:36 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of June 10 - 16, 2017 The Best of Broadway Kevin Spacey hosts the 71st Annual Tony Awards Massachusetts’ First Credit Union Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem The best and brightest theatre professionals gather St. Jean's Credit Union ET Filler to celebrate outstanding work in their field at The 3 x 3 1 x 3 71st Annual Tony Awards, airing Sunday, June 11, on Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 TO ADVERTISE HERE CBS. Broadcast from New York City’s legendary Radio Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs Contact Glenda City Music Hall, this year’s ceremony is hosted by Os- car, Golden Globe and Tony winner Kevin Spacey Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses 978-338-2540 or [email protected] (“House of Cards”). This year, James Earl Jones (“The • Great White Hope,” 1970) is honored with a Special 978.219.1000 www.stjeanscu.com Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Theater. Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere Federally Insured by NCUA FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 3, 2017 3:17:37 PM 2 • Salem News • June 10 - 16, 2017 The Tonys celebrate the best of the best on CBS By Kyla Brewer peers on Broadway. This year’s Benton finds herself in good aration” and Jefferson Mays for es,” “Driving Miss Daisy” and Video TV Media Tony contenders face some fierce company in the Best Performance “Oslo.” Legendary actress Sally “The Gin Game.” releases competition with 13 new musi- by an Actress in a Leading Role in Field leads the list of nominees for Also, director, actress and cho- roadway is having a mo- cals in contention for awards. -

Research on the Impact of Technology on Policing Strategy in the 21St

The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: Research on the Impact of Technology on Policing Strategy in the 21st Century, Final Report Author(s): Kevin Strom Document Number: 251140 Date Received: September 2017 Award Number: 2012-MU-CX-0043 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. May 2016 Research on the Impact of Technology on Policing Strategy in the 21st Century Final Report Prepared for Brett Chapman National Institute of Justice 810 7th Street, NW Washington, DC 20531 Phone: 202-514-2187 Fax: 202-616-0275 [email protected] Prepared by RTI International Police Executive Research Forum RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 Final Report NIJ Grant Number 2012-MU-CX-0043 RTI Project Number 0213507.000.003 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S.