Kocurek Dissertation 201221.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme Nr. 94 (Mai 2010)

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme -Kurzübersicht- Detaillierte Informationen finden Sie auf unserer Website und in unse- rem 14tägigen Newsletter Nr. 94 (Mai 2010) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS Talstr. 11 - 70825 Korntal Tel.: (0711) 83 21 88 - Fax: (0711) 8 38 05 18 INTERNET: www.laserhotline.de e-mail: [email protected] Katalog DVD BRD (Spielfilme) Nr. 94 Mai 2010 (500) Days of Summer 10 Dinge, die ich an dir 20009447 25,90 EUR 12 Monkeys (Remastered) 20033666 20,90 EUR hasse (Jubiläums-Edition) 20009576 25,90 EUR 20033272 20,90 EUR Der 100.000-Dollar-Fisch (K)Ein bisschen schwanger 20022334 15,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags 20032742 18,90 EUR Die 10 Gebote 20000905 25,90 EUR 20029526 20,90 EUR 1000 - Blut wird fließen! (Traum)Job gesucht - Will- 20026828 13,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags - High Noon kommen im Leben Das 10 Gebote Movie (Arthaus Premium, 2 DVDs) 20033907 20,90 EUR 20032688 15,90 EUR 1000 Dollar Kopfgeld 20024022 25,90 EUR 20034268 15,90 EUR .45 Das 10 Gebote Movie Die 120 Tage von Bottrop 20024092 22,90 EUR (Special Edition, 2 DVDs) Die 1001 Nacht Collection – 20016851 20,90 EUR 20032696 20,90 EUR Teil 1 (3 DVDs) .com for Murder 20023726 45,90 EUR 13 - Tzameti (k.J.) 20006094 15,90 EUR 10 Items or Less - Du bist 20030224 25,90 EUR wen du triffst 101 Dalmatiner (Special [Rec] (k.J.) 20024380 20,90 EUR Edition) 13 Dead Men 20027733 18,90 EUR 20003285 25,90 EUR 20028397 9,90 EUR 10 Kanus, 150 Speere und [Rec] (k.J.) drei Frauen 101 Reykjavik 13 Dead Men (k.J.) 20032991 13,90 EUR 20024742 20,90 EUR 20006974 25,90 EUR 20011131 20,90 EUR 0 Uhr 15 Zimmer 9 Die 10 Regeln der Liebe 102 Dalmatiner 13 Geister 20028243 tba 20005842 16,90 EUR 20003284 25,90 EUR 20005364 16,90 EUR 00 Schneider - Jagd auf 10 Tage die die Welt er- Das 10te Königreich (Box 13 Semester - Der frühe Nihil Baxter schütterten Set) Vogel kann mich mal 20014776 20,90 EUR 20008361 12,90 EUR 20004254 102,90 EUR 20034750 tba 08/15 Der 10. -

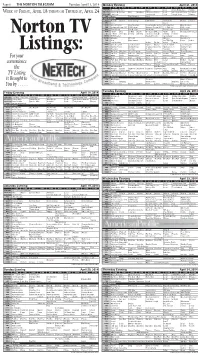

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 6/4/2019 Surprise That Borders Have Become So Porous

Losing Earth A Recent History Nathaniel Rich An instant classic: the most urgent story of our times, brilliantly reframed, beautifully told By 1979, we knew nearly everything we understand today about climate change—including how to stop it. Over the next decade, a handful of scientists, politicians, and strategists, led by two unlikely heroes, risked their careers in a desperate, escalating campaign to convince the world to act before it was too late. Losing Earth is their story, and ours. The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to Nathaniel Rich’s groundbreaking chronicle of that decade, which became an instant journalistic phenomenon—the subject of news coverage, editorials, and SCIENCE conversations all over the world. In its emphasis on the lives of the people who grappled with the great existential threat of our age, it made vivid the MCD | 4/9/2019 moral dimensions of our shared plight. 9780374191337 | $25.00 / $32.50 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 224 pages 4 Black-and-White Illustrations / Notes on Now expanded into book form, Losing Earth tells the human story of climate Sources | Carton Qty: 28 | 8.3 in H | 5.4 in W change in even richer, more intimate terms. It reveals, in previously unreported detail, the birth of climate denialism and the genesis of the fossil MARKETING fuel industry’s coordinated effort to thwart climate policy through disinformation, propaganda, and political influence. The book carries the National review attention Print features and profiles story into the present day, wrestling with the long shadow of our failures and Online features and profiles asking crucial questions about how we make sense of our past, our future, Interest-specific media outreach: environment and ourselves. -

The+Dawkins-Kardashian+Steal.Pdf (9.472Mb)

A PASTICHE on DOCUMENTATION of ARTISTIC RESEARCH by BJØRN JØRUND BLIKSTAD The Dawkins-Kardashian Stela Documentation of artistic research / KUF in the form of bas relief by Bjørn Jørund Blikstad, as part of a phd project, Level Up, on design from Oslo National Academy of the Arts 2019. Materials: Sipo/utile head and base Birch body Ultramarine surface, linseed oil paint Turned and chrome painted wooden ufo insert Eckart Bleichgold Made in 2019 from March to October by BJB at locations: Oslo National Academy of the Arts Tune Handel, Tørberget Ormelett, Tjøme Studio photography of stela 17.10.2019 by BJB & Olympus self timer Other images: Page 10: Furrysaken, Universitas 17.10.2018 (Henrik Follesø Egeland) Page 11: T-Shaped pilars from the excavation site at Göebekli Tepe, Turkey 2011. (Creative Commons) Page 12: Retouched kartouche, Karnak, Luxor 2011 (BJB) Page 13: Herma of Dionysos. Attributed to the Workshop of Boëthos of Kalchedon. Greek, active about 200 - 100 B.C. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) Page 14: Neues Reich. Dynastie XVIII. Pyramiden von Giseh. Stele vor dem grossen Sphinx. Litography by Ernst WeidenBach. (C C) Page 15: Illustration by Charles Eisen for The Devil of Pope-Fig Island by Jean de la Fontaine: Tales and Novels in Verse. London 1896. (C C) Standard fonts & formats ISBN: 978-82-7038-400-6 TO THE READER Don’t read the introduction to ufology first. Jump straight to the explanations of the have used to conceptualize alterity and change” (Astruc, 2010). By doing that, we constituent elements of the Stela (page 32) before continuing to the introduction, discover a predicament.