Arcade-Style Game Design: Postwar Pinball and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taito Pinball Tables Volume 1 User Manual

TAITO PINBALL TABLES VOLUME 1 USER MANUAL For all Legends Arcade Family Devices © TAITO CORPORATION 1978, 1982, 1986, 1987 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Version 1.7 | September 1, 2021 Contents Overview ............................................................................................................1 DARIUS™ .............................................................................................................2 Description .......................................................................................................2 Rollovers ..........................................................................................................2 Specials ...........................................................................................................2 Standup Targets ................................................................................................. 2 Extra Ball .........................................................................................................2 Hole Score ........................................................................................................2 FRONT LINE™ ........................................................................................................3 Description .......................................................................................................3 50,000 Points Reward ...........................................................................................3 O-R-B-I-T Lamps ................................................................................................ -

Pioneering E-Sport: the Experience Economy and the Marketing of Early 1980S Arcade Gaming Contests

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 2254-2274 1932–8036/20130005 Pioneering E-Sport: The Experience Economy and the Marketing of Early 1980s Arcade Gaming Contests MICHAEL BOROWY DAL YONG JIN Simon Fraser University This article sets out to historicize the development of e-sport (organized competitive digital gaming) in the early 1980s using three new conceptual frameworks. We identify e-sport as an accompaniment of the broader embryonic gamer culture, a hallmark of the “experience economy” concept, and as a succession of consumer practices whose development was coterminous with the rise of event marketing as a leading promotional business strategy. By examining the origins of e-sport as both a marketized event and experiential commodity, we see this period as a transitory era bridging different phases in the areas of sports, marketing, and technology, resulting in the expansion of competitive cyberathleticism. Keywords: e-sport, professional gamer, arcade, experience economy, event marketing, video games, public events Introduction In the early 2000s, competitive player-versus-player digital game play (henceforth e-sports) has been a heavily promoted feature of overall gamer culture. Although e-sport—known as an electronic sport and the leagues in which players compete through networked games and related activities (Jin, 2010)— has existed since the early 1980s, the increased attention toward the activity in the 21st century has signaled that the gaming industry is adopting more flexible avenues of public event consumption with the goal of generating higher profit margins. While stand-alone e-sports events are common, their use as adjuncts of other industry events, including major trade shows, press conferences, and even traveling orchestras, demonstrates that competitive gaming continues to play a major role in the machinery of game industry event marketing. -

Aerosmith Operation and Parts Manual

AEROSMITH SERVICE AND OPERATION MANUAL WARNING IMPORTANT HEALTH WARNING: PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES - A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, in- cluding flashing lights or patterns. Even people with no history of seizures of epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” due to certain visual images, flashing lights or patterns. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. IMMEDIATELY STOP PLAYING AND CONSULT A DOCTOR IF YOU EXPERIENCE ANY OF THESE SYMPTOMS. Stern Pinball machines are assembled in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, USA; each pinball machine has unique characteristics that make it a one-of-a-kind American-made product. Each machine will have variations in appearance resulting from differences in the machine’s particular wood parts, individual silk screened art and mechanical assemblies. Stern Pinball has inspected each game element to ensure it meets our quality standards. © 2016 Rag Doll Merchandising, Inc. Under License to Epic Rights. Games configured for North America operate on 60 cycle electricity only. These games will not operate in countries with 50 cycle electricity (Europe UK, Australia). MANUAL #780-50I5-00 AEROSMITH PRO #500-55I5-01 1-800-KICKERS - [email protected] www.sternpinball.com - facebook.com/sternpinball TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Setup and Moving .................................. 3 5.9 Auto Launch Assembly ...................................... 36 1.1 First-Time Setup Instructions .............................. -

COLORADO's ULTIMATE PINBALL and GAMER FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE Play Hundreds of Pinball and Classic Arcade Video Games May 25-27

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 7, 2019 Contact: Dan Nikolich 303-883-2603 Holly Nikolich 303-638-2119 [email protected] COLORADO'S ULTIMATE PINBALL AND GAMER FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE Play hundreds of pinball and classic arcade video games May 25-27 Denver, Colo., May 25-27, 2019, Memorial Day weekend is right around the corner. School is out. Pinball and arcade games are in! A great way to kick-off your summer with three amazing days in Denver with hundreds of pinball and classic arcade games to play for free with admission. Check out the new 25,000 square foot, air-conditioned festival space at the Denver Marriott Tech Center. Grab the friends and escape, bring the family, make it a weekend away, an awesome date night, or dare we say play hooky from work? Experience the sights, sounds, and excitement of hands-on games. Enjoy playing hundreds of pinball and arcade games for 32 plus hours -- No Quarters Needed. Play for fun, or opt-in to compete in pinball tournaments for all ages and skill levels with trophies, cash, prizes and glory. A full slate of casual and friendly tournaments challenges individuals, rookies, kids, parent-kid teams, and more. The festival's sanctioned tournaments pit a player's skills against the best and highest ranked competitive pinball players in the world. Can you handle it? Play in the Horrorhouse Fest Pinball Tournament of Death, a spooktacular haunted pinball tournament for glory and prizes. The festival brings special guests from industry and the community to give fans great opportunities to interact with awesome personalities, to discuss timely topics, and to brings a fresh, in-demand perspective of our wider community. -

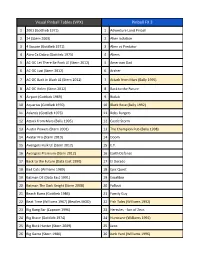

Pinball Game List

Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 1 Adventure Land Pinball 2 24 (Stern 2009) 2 Alien Isolation 3 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) 3 Alien vs Predator 4 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) 4 Aliens 5 AC-DC Let There Be Rock LE (Stern 2012) 5 American Dad 6 AC-DC Luci (Stern 2012) 6 Archer 7 AC-DC Back in Black LE (Stern 2012) 7 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 8 AC-DC Helen (Stern 2012) 8 Back to the Future 9 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) 9 Biolab 10 Aquarius (Gottlieb 1970) 10 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 11 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 11 Bobs Burgers 12 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 12 Castle Storm 13 Austin Powers (Stern 2001) 13 The Champion Pub (Bally 1998) 14 Avatar Pro (Stern 2010) 14 Doom 15 Avengers Hulk LE (Stern 2012) 15 E.T. 16 Avengers Premium (Stern 2012) 16 Earth Defense 17 Back to the Future (Data East 1990) 17 El Dorado 18 Bad Cats (Williams 1989) 18 Epic Quest 19 Batman DE (Data East 1991) 19 Excalibur 20 Batman The Dark Knight (Stern 2008) 20 Fallout 21 Beach Bums (Gottlieb 1986) 21 Family Guy 22 Beat Time (Williams 1967) (Beatles MOD) 22 Fish Tales (Williams 1992) 23 Big Bang Bar (Capcom 1996) 23 Hercules - Son of Zeus 24 Big Brave (Gottlieb 1974) 24 Hurricane (Williams 1991) 25 Big Buck Hunter (Stern 2009) 25 Jaws 26 Big Game (Stern 1980) 26 Junk Yard (Williams 1996) Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 27 Big Guns (Williams 1987) 27 Jurassic Park 28 Black Knight (Williams 1980) 28 Jurassic Park Pinball Mayhem 29 Black Knight 2000 (Williams 1989) 29 Jurassic World 30 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 30 Mars 31 Blue Note (Gottlieb 1979) 31 Marvel - Age of Ultron 32 Bram Stoker's Dracula (Williams 1993) 32 Marvel - Ant-Man 33 Bronco (Gottlieb 1977) 33 Marvel - Blade 34 Bubba the Redneck Werewolf (2018) 34 Marvel - Captain America 35 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1976) 35 Marvel - Civil War 36 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 36 Marvel - Deadpool 37 Bugs Bunny B. -

STERN RELEASES Big Buck Hunter® PRO PINBALL to MUCH ACCLAIM

PRESS RELEASE STERN RELEASES Big Buck Hunter® PRO PINBALL TO MUCH ACCLAIM January 13, 2010--Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball by Stern Pinball, Inc. is a hunting game that delivers a hot new quarry of no-limit fun to players everywhere. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball is based on the hugely successful Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game series by Raw Thrills, Inc. and Play Mechanix, Inc. Eugene Jarvis, George Petro, and Mark Ritchie of Raw Thrills/Play Mechanix assisted the staff at Stern Pinball with the design of Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball. And like the arcade video games, Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball is sure to challenge new hunters, as well as seasoned marksmen. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball takes you on a hunting adventure. Players are in pursuit of wild game. The game features a motorized buck that runs across a forest-like playfield. Strike the buck multiple times and start Big Buck Multiball. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball also features a ramp that winds around the playfield, a ram that kicks the ball back to the player, an elk mechanism that re-directs the pinball, and lots of multiball action. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball features speech from the video game. George Petro, narrator of the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game series narrates the Pinball machine while contributing additional original speech. Pappy, voiced by Scott Pikulski, also appears offering comic relief. John Youssi, creator of the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game art, contributes the art for the pinball. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball also features sounds and music by Ken Hale, the sound engineer for the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Games. -

1080-Pinballgamelist.Pdf

No. Table Name Table Type 1 12 Days Christmas VPX Table 2 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 3 24 (Stern 2009) VP 9 Table 4 250cc (Inder 1992) VP 9 Table 5 4 Roses (Williams 1962) VP 9 Table 6 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 7 Aaron Spelling (Data East 1992) VP 9 Table 8 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) VP 9 Table 9 ACDC (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 10 ACDC Pro - PM5 (Stern 2012) PM5 Table 11 ACDC Pro (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 12 Addams Family Golden (Williams 1994) VP 9 Table 13 Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends (Data East 1993) VP 9 Table 14 Aerosmith Future Table 15 Agents 777 (GamePlan 1984) VP 9 Table 16 Air Aces (Bally 1975) VP 9 Table 17 Airborne (Capcom 1996) VP 9 Table 18 Airborne Avenger (Atari 1977) VP 9 Table 19 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) VP 9 Table 20 Aladdin's Castle (Bally 1976) VP 9 Table 21 Alaska (Interflip 1978) VP 9 Table 22 Algar (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 23 Ali (Stern 1980) VP 9 Table 24 Ali Baba (Gottlieb 1948) VP 9 Table 25 Alice Cooper Future Table 26 Alien Poker (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 27 Alien Star (Gottlieb 1984) VP 9 Table 28 Alive! (Brunswick 1978) VPX Table 29 Alle Neune (NSM 1976) VP 9 Table 30 Alley Cats (Williams 1985) VP 9 Table 31 Alpine Club (Williams 1965) VP 9 Table 32 Al's Garage Band Goes On World Tour (Alivin G. 1992) VP 9 Table 33 Amazing Spiderman (Gottlieb 1980) VP 9 Table 34 Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 1983) VP 9 Table 35 America 1492 (Juegos Populares 1986) VP 9 Table 36 Amigo (Bally 1973) VP 9 Table 37 Andromeda (GamePlan 1985) VP 9 Table 38 Animaniacs SE Future Table 39 Antar (Playmatic 1979) -

CB-1990-03-31.Pdf

TICKERTAPE EXECUTIVES GEFFEN’S NOT GOOFIN’: After Dixon. weeks of and speculation, OX THE rumors I MOVE I THINK LOVE YOU: Former MCA Inc. agreed to buy Geffen Partridge Family bassist/actor Walt Disney Records has announced two new appoint- Records for MCA stock valued at Danny Bonaduce was arrested ments as part of the restructuring of the company. Mark Jaffe Announcement about $545 million. for allegedly buying crack in has been named vice president of Disney Records and will of the deal followed Geffen’s Daytona Beach, Florida. The actor develop new music programs to build on the recent platinum decision not to renew its distribu- feared losing his job as a DJ for success of The Little Mermaid soundtrack. Judy Cross has tion contract with Time Warner WEGX-FM in Philadelphia, and been promoted to vice president of Disney Audio Entertain- Inc. It appeared that the British felt suicidal. He told the Philadel- ment, a new label developed to increase the visibilty of media conglomerate Thom EMI phia Inquirer that he called his Disney’s story and specialty audio products. Charisma Records has announced the appointment of Jerre Hall to was going to purchase the company girlfriend and jokingly told her “I’m the position of vice president, sales, based out of the company’s for a reported $700 million cash, going to blow my brains out, but New York headquarters. Hall joins Charisma from Virgin but David Geffen did not want to this is my favorite shirt.” Bonaduce Records in Chicago, where he was the Midwest regional sales engage in the adverse tax conse- also confessed “I feel like a manager. -

Artificial Intelligence in Racing Games

BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science ABDAL MOHAMED BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Sections 1. History of AI in Racing Games 2. Neural Networks in Games BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science History Gran Trak 10 Single-player racing arcade game released by Atari in 1974 Did not have any AI Pole Position Single- player racing game released by Namco in 1982 Considered first racing game with AI BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science History Super Mario Kart Addition of Power Ups Released in 1992 for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Driver Free- form World 1998 video game developed by Reflections Interactive Vehicular Combat: Power Ups + Free Form World BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Simple Areas of AI in Racing Games 1. Steering Sort of Basic Used in Formula One-Built to win, GTA3 2001 for background animation purpose. 2. Pathfinding Becomes more free-form world Would need to make decision on where to go. Need to find the best path between two points, avoiding any obstacles. BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Steering + Racing Lines Racing Lines methods was used extensively until there was CPU power to do something else. It is just a drawn line in which the cars follow that line or stuck to that line. It uses Spline, where addition information such as velocity is included. Advantage It is very easy to create cheap spine creation tool Disadvantage Very limited- and gets very difficult Not very realistic- as car follows line, no response to deflection BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Pathfinding + Tactical AI Racing line does not really work with free-form world so one of the solutions is having set path to where the car/ character is fleeing. -

Big Dog Pounder

WARNING Be sure to read this Operation Manual before using your machine to ensure safe operation. JULY 2008 BOB’S SPACE RACERS® DOG POUNDER™ ARCADE (AIR VERSION) DOG POUNDER™ ARCADE Air Version 2 BOB’S SPACE RACERS® DOG POUNDER™ ARCADE (AIR VERSION) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SPECIFICATIONS 2. INTRODUCTION 2-1. Overview and Technical Features: 2-2. Important Safety Information: 3. PROGRAMMING 3-1. Entering Programming Mode: 3-2. Volume: 3-3. Coins per Credit: 3-4. Attract Mode: 3-5. Game Type: 3-6. Game Difficulty: 3-7. Minimum Tickets: 3-8. Balls per Ticket: 3-9. Bonus Ticket Value: 3-10. Hand: 3-11. Reset: 3-12. Programming Options: 4. ERROR MESSAGES 5. MAINTENANCE AND TROUBLESHOOTING 5-1. Quick Troubleshooting: 5-2. Detailed Troubleshooting and Repair: 5-2-1. Mechanical / Motor Repair: Hammock Replacement Pivot Mechanism Ground Wire Replacement Actuator Motor Replacement 5-2-2. Electronic / Electrical Repair: Main P.C. Board Replacement Score Sensor Replacement Playfield Light Replacement 6. PARTS LISTINGS 7. SCHEMATICS 8. WARRANTY 3 BOB’S SPACE RACERS® DOG POUNDER™ ARCADE (AIR VERSION) 1. SPECIFICATION IMPORTANT SETUP INFORMATION CENTER LEVELER ADJUSTMENT – The center foot leveler adjustment is critical to the proper operation of the game. The purpose of this adjuster is to control cabinet vibration to prevent damage to electronic and other components in the game. When the adjuster is properly contacting the floor, any force from the mallet that is CENTER transmitted through the pivot mechanism will be transmitted LEVELER directly to the floor and NOT the bottom of the cabinet. It is important to make sure the weight of the game is equally distributed across all 5 legs to avoid rocking and damage. -

Roadshow Shrine Road Show

RoadShow Shrine Road Show (for LA-4 and LA-5 ROMs), Version 2.0 (April 9, 1995) Contents: ❍ Changes from Version 1.1 ❍ History and Thanks ❍ Overview ❍ Playfield Description ❍ General Rules and Scoring ❍ Blast ❍ Flying Rocks ❍ The Wheel ❍ Souvenirs ❍ Multiball ❍ City Scenes (Modes) ❍ Super Payday (Wizard Bonus) ❍ The Magic Standup ❍ Combos ❍ Easter Eggs and Cheats ❍ Bugs ❍ Miscellaneous Stuff ❍ Operator Adjustments ❍ Strategies Changes from Version 1.1: ❍ Scott now has access to an LA-5 machine, so some info on L-5 has been added. ❍ Scott's email address has changed. ❍ Corrected info on the Magic Standup. It turns out that it's more powerful than we thought before! ❍ Added the value of Fun With Bonus. file:///D|/Pinballs/RoadShow_htm/Roadshow2.htm (1 of 43) [4/22/2001 4:33:24 PM] RoadShow Shrine ❍ Added operator adjustments as section 17. Thanx to Cameron Silver for providing the list of adjustments. ❍ Added that a mode won't start if you collect Bad Weather at the Blast Hole. ❍ Added a few more joke souvenirs. ❍ Added a note about how the status report shows the number of locks. ❍ Added in what happens after you complete all the cities. ❍ Added a few more bugs. ❍ Added in a point-scoring strategy (go for all the souvenirs you can). ❍ Fixed up the quotes (Scott did all of the work here). ❍ Fixed up a *lot* of little details here and there. Top History and Thanks: Version 2.0: Major revision that incorporated lots of changes and fixes. The section of operator adjustments was added. Version 1.1: This was a quick update to fix the glaring goofs in 1.0. -

Art 384: Introduction to 3D Modeling

Bowls, Bocce and Shuffleboard • go back to at least the 12th century – maybe Roman? from shotputting? • played outdoors, which is a problem in winter! Billiards • Bowls, moved indoors, ~1550 • “Billiards” was a generic name for many games. Bagatelle • Invented in 1777 by making a narrow Billiards table with many obstacles. Penny Arcades • Businesses that operated rooms full of mechanical contraptions that customers would pay to operate for a short time • Often part of other businesses: bars, diners. Pinball • Bagatelle with lights and bells and mechanical contraptions • Many patents! • The companies who made arcade games generally were old pinball manufacturers Old games: why, again? • You can see ideas evolving, being led by tech-- you can see the conversation • These games are still marketable – youtube.com/watch?v=OyfP3ZG-42Y • Spare parts for your game – or! paste-ready minigames • Small size compared to AAA’s like BioShock; feasible scope • Your history, letting names be known • Smaller games; easier to discuss Cinematronics, corrections! • Tailgunner, Unknown vectorbeam employee (1979) – Actual 3D – youtube.com/watch?v=V4hb9UJBs9k • Armor Attack, Tim Skelly, 1980 – youtube.com/watch?v=eA9HN8ywIiY • Star Castle, Skelly & UVE, 1980 – youtube.com/watch?v=EGIOSGRm5Sc • Reactor, Tim Skelly, 1982 – youtube.com/watch?v=bKzx1mBV2PU Cinematronics/Skelly • Rip Off, Tim Skelly, 1980 – Infinite ship supply; you defend pods from raiders, who shoot you and steal them. – First collaborative multiplayer? – youtube.com/watch?v=3-EDILMmpos • Cautionary note about all of Wikipedia – it is wrong too much – userpages.umbc.edu/~mcdo/380/reading/Skelly3.pdf Galaxian • Kazunori Sawano, Koichi Tashiro, and Shige Ishimura, 1979, for Namco • Non-overlay color, a theme song.