Boobs, Boxing, and Bombs: Problematizing the Entertainment of Spike TV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday Striving for Imperfection

Community YOUR HEALTH sports digest Tuesday Striving for Imperfection ...................................Page 3 .............Page 6 Nov. 25, 2008 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Wednesday: Partly sunny; H 62º L 39º 7 58551 69301 0 Thursday: Cloudy H 61º L 42º 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 14 pages, Volume 150 Number 230 email: [email protected] 2008 ELECTION RESULTS Final county election results same as initial estimates The Daily Journal At 9:21 a.m. Monday the Mendocino County Assessor/Clerk/Recorder’s office issued the results for the Nov. 4 election and nothing has changed from the initial results. In the 1st District supervisor race, incumbent Michael Delbar was able to tighten the gap between him and his chal- lenger Carre Brown slightly by garnering 3,020 votes (39.55 percent) to her 4,582 votes (60.01 percent.) On Election Night, Brown held a commanding lead over Delbar with 2,710 votes (60.26 percent) to his 1,772 votes (39.4 percent.) In the 2nd District supervisor race, Ukiah City Councilmember John McCowen was able to increase his lead by nearly a point over challenger Estelle Palley Clifton with 3,335 votes (53.69 percent) to her 2,858 votes (46.01 percent.) On Election Night, Clifton was trailing McCowen with 1,632 votes (46.82 percent) to his 1,846 votes (52.95 percent.) In the race for Ukiah Valley Sanitation District, Michael Pallesen (1,952 votes, 20.46 percent,) Clifford Paulin (1,468 votes, 15.38 percent,) Theresa McNerlin (1,644 votes, 17.23 percent,) James-John Ronco (1,352 votes, 14.17 percent) and Jason Hooper (1,265 votes, 13.26 percent) will represent the Sarah Baldik/The Daily Journal first elected board in organization’s history. -

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

Tv Tronics Saturday, May 28 • 9:00 A.M

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON 4-6 p.m. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Space is limited. • Wednesday, May 11 with Shack Happy with Shack of Lanny’s Fireside of Lanny’s Cooking Demo with Spring Cleaning Tips Spring Cleaning Chef Lanny Studdard Chef Lanny *Advance registry required. *Advance House Cleaning Services Page 1 Page and explore the options of a gourmet and explore kitchen their services. Saturday, 4 DAY • Visit with factory rep from Sub-Zero/Wolf • out Visit with the pros and check May 7,May 2011 (715) 479-4421 A SPECIALTHE SECTION OF AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW 1-2 p.m. 10 a.m. - 2 p.m. 10 a.m. - 1 p.m. hance to win a Kitchenaid blender. hance to win a Kitchenaid 4-6 p.m. KINS KINS with Mark of • Tuesday, May 10 Of Course! • Saturday, 14 May Space is limited, make your reservations soon. reservations your r, WI • www.JensenAkins.com • 715.479.8427 WI • www.JensenAkins.com r, *Advance registry required. *Advance Wine & Cheese Tasting Wine & Cheese Plant A Can - with Bill Hogenmiller - Forest Lake Country Store Peri Tennikait Peri DAY 3 DAY Cabinet & Countertop Makeover DAY 7 DAY Weber Grill Demo - Weber • Queen,” Worm “The kids with Activity for • Register to win wine chiller A A with • Friday, 13 May • Monday, 9 May May 7-14, 2011 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. -

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

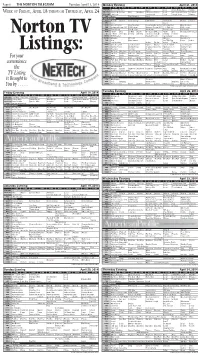

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 20 Issue 2 Article 4 2013 Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts Daniel Berger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Berger, Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts, 20 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 381 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol20/iss2/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\20-2\VLS204.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUN-13 13:05 Berger: Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ul Articles CONSTITUTIONAL COMBAT: IS FIGHTING A FORM OF FREE SPEECH? THE ULTIMATE FIGHTING CHAMPIONSHIP AND ITS STRUGGLE AGAINST THE STATE OF NEW YORK OVER THE MESSAGE OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS DANIEL BERGER* I. INTRODUCTION The promotion-company -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

Ufc Fight Night Features Exciting Middleweight Bout

® UFC FIGHT NIGHT FEATURES EXCITING MIDDLEWEIGHT BOUT ® AND THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE ON FOX SPORTS 1 APRIL 16 Two-Hour Premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER: TEAM EDGAR VS. TEAM PENN Follows Fights on FOX Sports 1 LOS ANGELES, CA – Two seasons of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER® converge on FOX Sports 1 on Wednesday, April 16, when UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: BISPING VS. KENNEDY features THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS welterweight and middleweight finals, the coaches’ fight and an exciting headliner between No. 5-ranked middleweight Michael Bisping (25-5) and No. 8- ranked Tim Kennedy (17-4). FOX Sports 1 carries the preliminary bouts beginning at 5:00 PM ET, followed by the main card at 7:00 PM ET from Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Immediately following UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BISPING VS. KENNEDY is the two-hour season premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER®: TEAM EDGAR vs. TEAM PENN (10:00 PM ET), highlighting 16 middleweights and 16 light heavyweights battling for a spot on the team of either former lightweight champion Frankie Edgar or two-division champion BJ Penn. UFC on FOX analyst Brian Stann believes the headliner between Bisping and Kennedy is a toss-up. “Kennedy has one of the best top games in mixed martial arts and he’s showcased his knockout power in his last fight against Rafael Natal. Bisping is one of the best all-around mixed martial artists in the middleweight division. Every time people start to count him out, he comes in and wins fights.” In addition to the main event between Bisping and Kennedy, UFC FIGHT NIGHT consists of 12 more thrilling matchups including THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS Team Canada coach Patrick Cote (20-8) and Team Australia coach Kyle Noke (20-6-1) in an exciting welterweight bout. -

The Ultimate Fighter: the Aftermath'

Spike Presents New Original Online Show 'The Ultimate Fighter: The Aftermath' Spike.com Greenlights Digital Series Hosted By Amir Sadollah As Companion To The Most Successful Franchise In Network History NEW YORK, Sept. 22 -- Spike TV's hit series "The Ultimate Fighter" has propelled mixed martial arts into the American mainstream while becoming the most successful franchise in the network's history. With its tenth iteration having premiered to record ratings, Spike.com will launch the original series "The Ultimate Fighter: The Aftermath." Hosted by Amir Sadollah, the new show will be a video roundtable discussion about the on-air episode that precedes it, with the fighters that competed in an elimination bout on hand to talk about what went on, both inside and outside of the Octagon™, during "The Ultimate Fighter: Heavyweights." (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20060322/NYW096LOGO ) "'The Ultimate Fighter: Heavyweights' promises to be the show's biggest season yet, and Spike.com has enjoyed great success with its 'Aftermath' franchise," said Jon Slusser, SVP, Spike digital entertainment. "In combining the two, this new show will deliver exclusive content to our audience, and allow Spike viewers and members of our online community to interact with our signature franchise in new ways." Premiering Tuesday, September 22 on Spike.com, "The Ultimate Fighter: The Aftermath" will allow fans, for the first time in the show's history, to pose their questions about "The Ultimate Fighter: Heavyweights" directly to the fighters involved. UFC® president Dana White will be on hand for the premiere episode, and, over the course of the season, coaches Rashad Evans and Rampage Jackson, as well as the show's entire cast, including Kimbo Slice, Wes Sims, Marcus Jones, and Roy Nelson, will stop by to take part in "The Aftermath." "Ten seasons in, and 'The Ultimate Fighter' still packs as much of a punch as ever," said Brian J. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Wednesday Morning, Jan. 27

WEDNESDAY MORNING, JAN. 27 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 47008 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View Journalist E.D. Hill. (N) Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 626517 (cc) 17282 21973 (cc) (TV14) 59843 (TVG) 46379 KOIN Local 6 News 33331 The Early Show (N) (cc) 69244 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right Contestants bid The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 Early at 6 80824 66244 for prizes. (N) (TVG) 88379 (TV14) 91843 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Gayle Haggard; Sharon Osbourne. (N) (cc) 867060 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 86911 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 44534 Lilias! (cc) (TVG) Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Tribute to Number Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 19350 (TVY) 89517 (TVY) 25824 Kid (TVY) 43701 (TVY) 27718 (TVY) 26089 Seven. (N) (cc) (TVY) 35398 Red Dog 91379 (TVY) 39553 11060 (TVY) 29089 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 71602 Good Day Oregon (N) 16176 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 20466 Paid 86447 Paid 24621 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 15447 Paid 86486 Paid 17008 Paid 49195 Paid 28602 Through the Bible Life Today 15553 Christians & Jews Paid 34176 Paid 91060 Paid 67319 Paid 78244 Paid 79973 22/KPXG 5 5 16282 67355 Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- The Word in the Inspirations Lifestyle Maga- Behind the Alternative James Robison Marilyn -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal