Research on the Impact of Technology on Policing Strategy in the 21St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

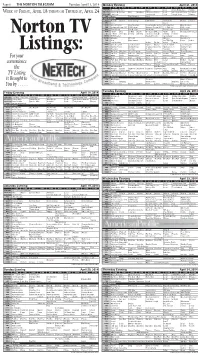

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

The Purpose of This Concept Paper Is to Explore Compstat and Citistat—Two Municipal Management Techniques Introduced in the Ne

November 2006 Discussion Version Budget Office Evaluation, Matt Nice INNOVATIVE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT IN MULTNOMAH COUNTY: MULTSTAT CONCEPT PAPER The purpose of this concept paper is to explore databases to track all aspects of government program Compstat and Citistat—two municipal management performance to align with policy. The process goes techniques introduced in the New York City Police beyond traditional collection of performance data, by Department and the City of Baltimore, respectively—at providing analysis of key measures, providing Multnomah County. The goals are to increase information, trends and identifying issues. This data is accountability, and improve the performance of presented through maps, charts, tables and graphs in government agencies and their service outcomes. weekly closed executive forums with management. “STATS” are a structured continuous management process for ongoing review of government agencies’ These forums allow the executive and others to performance indicators measuring utilization of assess whether departments are meeting immediate available resources and delivery of services to the and long-term goals, and help to determine strategies public, with a specific focus upon immediate results. to best respond to emerging issues. Background. The history of performance There are four basic process principles for STAT measurement in Multnomah County has been marked models: by ebbs and flows in both the quantity and quality of 1) provide timely, accurate and relevant data available data. Currently, the Priority Briefs provide 2) analyze data and develop effective solutions timely and accurate workload data for a variety of that respond to emerging issues basic needs and safety system measures each month. 3) deploy resources quickly to address issues As a part of the annual Priority-Based Budgeting 4) relentless follow-up and assessment process all County programs now report outcome- based performance measures. -

2016 Police Commissioner's Report

THE POLICE COMMISSIONER’S REPORT JANUARY 2016 THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT 22 40 58 INFORMATION HOUSING BUREAU RISK MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGY BUREAU BUREAU TABLE OF CONTENTS 26 42 60 DETECTIVE BUREAU VIOLENCE- PERSONNEL REDUCTION TASK BUREAU / STAFFING FORCES 44 ORGANIZED CRIME 62 28 CONTROL BUREAU PERSONNEL COLLABORATIVE BUREAU / REFORM 4 POLICING 46 AND RECRUITMENT TRANSPORTATION LETTER FROM 30 BUREAU 64 THE MAYOR CRITICAL RESPONSE CIVILIAN MEMBERS 6 COMMAND 48 FIELD INTELLIGENCE 66 LETTER FROM 32 OFFICERS THE POLICE FACILITIES COMMISSIONER STRATEGIC RESPONSE GROUP 50 68 10 GRAND LARCENY 34 DIVISION CARS & EQUIPMENT NEIGHBORHOOD POLICING PLAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS BUREAU / YOUTH PROGRAMS 52 70 14 ADMINISTRATION STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS COMPSTAT 36 COMMUNITY 54 AFFAIRS BUREAU / 72 16 SCHOOL SAFETY USE-OF-FORCE DIVISION POLICY 2014 / 2015 STATISTICAL TRAINING BUREAU ROUNDUP 20 38 56 76 TRANSIT BUREAU DISCIPLINE COMMUNITY NYPD HISTORICAL PARTNER PROGRAM TIMELINE SPRING 3100 ISSN #0038 8572 is published bimonthly by the New York City Police Department, One Police Plaza, New York, 10038. Periodicals postage paid at New York City, NY. “Ride-Along Enclosed” Postmaster: Send address changes to SPRING 3100 c/o New York City Police Department, One Police Plaza, New York, 10038. SPRING 3100 ©2014 BY NYPD. All rights reserved; No part of this publication may be reproduced without written consent of the Editor. L E T T ER FROM MAYOR BILL DE BLASIO appointed Bill Bratton to be New York City Police Department’s technological infrastructure; new use-of-force ICommissioner in January 2014, and, two years later, this policies and procedures; a more efficient and fairer internal report—about the sweeping changes in the NYPD— discipline system; 1,300 new officers; new technological underscores my reasons for doing so. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: an Evidence-Based Proposal

Volume 65 Issue 3 Villanova Law Review Article 3 10-7-2020 Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Evidence-Based Proposal Mitch Zamoff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Mitch Zamoff, Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: Anvidence-Based E Proposal, 65 Vill. L. Rev. 585 (2020). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Zamoff: Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Ev 2020] DETERMINING THE PERSPECTIVE OF A REASONABLE POLICE OFFICER: AN EVIDENCE-BASED PROPOSAL MITCH ZAMOFF* ABSTRACT Excessive force jurisprudence in America is in disarray. Although the Supreme Court mandated over thirty years ago that courts determine the constitutionality of allegedly excessive force from the perspective of a rea- sonable officer on the scene, courts have never seemed more confused about how to make that determination. Without any definitive guidance on what evidence to consider in determining how a reasonable officer on the scene of an incident of allegedly excessive force would have behaved, courts are issuing haphazard, inconsistent decisions that are often difficult to reconcile -

The New York City Police Department's Compstat Model Of

Managing for Results Series August 2001 Using Performance Data for Accountability: The New York City Police Department’s CompStat Model of Police Management Paul E. O’Connell Associate Professor Department of Criminal Justice Iona College The PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment for The Business of Government The PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment for The Business of Government About The Endowment Through grants for Research and Thought Leadership Forums, The PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment for The Business of Government stimulates research and facilitates discussion on new approaches to improving the effectiveness of government at the federal, state, local, and international levels. Founded in 1998 by PricewaterhouseCoopers, The Endowment is one of the ways that PricewaterhouseCoopers seeks to advance knowledge on how to improve public sector effec- tiveness. The PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment focuses on the future of the operation and management of the public sector. Using Performance Data for Accountability: The New York City Police Department’s CompStat Model of Police Management Paul E. O’Connell Associate Professor Department of Criminal Justice Iona College August 2001 Using Performance Data for Accountability 1 2 Using Performance Data for Accountability TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ......................................................................................5 Executive Summary ......................................................................6 The New York City Police Department’s CompStat Program ........8 A Shift in -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Fiscal 1999 the City of New York

Click to Enter The City of New York Fiscal 1999 Summary Volume RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI MAYOR JOSEPH J. LHOTA DEPUTY MAYOR FOR OPERATIONS ADAM L. BARSKY DIRECTOR, MAYOR’S OFFICE OF OPERATIONS S UMMARY V OLUME TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................i Continuing Development of the Mayor’s Management Report...................iii Neighborhood Quality of Life................................................................................................1 Special Focus: Mayor’s Commission to Combat Family Violence ... 37 Managing the Workforce ....................................................................................................... 47 Economic Development ......................................................................................................... 53 Special Focus: Competitive Grants to NYC Agencies ............................ 69 Services for Children and Youth ..................................................................................... 73 Customer Service........................................................................................................................ 97 Managing Mandated Services......................................................................................... 111 Technology Initiatives........................................................................................................... 125 Special Focus: Preparing for the Year 2000 .............................................. 139 Agency