The Thin Blurred Line: Reality Television and Policing Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

Representations of British Probation

British Journal of Community Justice ©2012 Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield ISSN 1475-0279 Vol. 10(2): 5-23 REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH PROBATION OFFICERS IN FILM, TELEVISION DRAMA AND NOVELS 1948-2012 Mike Nellis, Emeritus Professor of Criminal and Community Justice, School of Law, University of Strathclyde Abstract This paper offers an overview of representations of the British probation service in three fictional media over a sixty year period, up to the present time. While there were never as many, and they were never as renowned as representations of police, lawyers and doctors, there are arguably more than has generally been realised. Broadly speaking - although there have always been individual exceptions to general trends - there has been a shift from supportive and optimistic representations to cynical and disillusioned ones, in which the viability of showing care and compassion to offenders is questioned or mocked. This mirrors wider political attempts to change the traditionally welfare-oriented culture of the service to something more punitive. The somewhat random and intermittent production of probation novels, films and television series over the period in questions has had no discernible cumulative impact on public understanding of probation, and it is suggested that the relative absence of iconic media portrayals of its officers, comparable to those achieved in police, legal and medical fiction, has made it more difficult to sustain credible debates about rehabilitation in popular culture. Introduction One of the problems the Probation Service has is that it is not very photogenic. We live with an image driven media and society and unfortunately probation doesn’t present itself well, certainly on television. -

RADYR CHAIN Free to Every Home in Radyr and Morganstown Number 198 February 2012

Radyr ‘SPAR” Open Day following their refurbishment The new refurbished shop front New wider aisles for customers’ ease of movement Steve, Jeff, Janet and Karen with Heather, a grateful customer Janet and Karen with free wines samples and nibbles for the day STATION ROAD, RADYR OPEN: Mon to Sat 8a.m. - 10.00p.m. Sunday 9a.m. - 10.00p.m. All services come with quality and value General Groceries - Chilled Foods & Ready Meals - Fresh Bread Daily Confectionery - Fruit & Vegetables - Crisps & Snacks - Ice Cream Quality Wines - Beers, Lagers & Ciders Cigarettes & Tobacco - Photocopying - Greetings Cards - Phone top-up Cards Children investigating their ‘Goody Bags’ NOW AVAILABLE MAKE SURE YOU COME AND VISIT OUR COMPLETELY REFURBISHED PREMISES - NOW WITH AUTOMATIC ENTRANCE DOORS FOR EASY ACCESS FOR ALL CUSTOMERS. WIDER AISLES FOR EASIER MOVEMENT, UPGRADED COOL AND County Councillor Rod McKerlich samples FREEZER CABINETS some wine Printed by J & P Davison, 3 James Place, Treforest, Pontypridd CF37 1SQ Tel. 01443 400585 RADYR CHAIN Free to every home in Radyr and Morganstown Number 198 February 2012 Christmas scene in Station Road See article on page 7 Radyr resident travels to Ecuador… Jodie Davis, who resides in Penrhos, Radyr is a normal teenage girl. She is currently studying for her A levels in Welsh, Drama and Religious Education as Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Plasmawr in Fairwater. She enjoys going out with her friends, watching films, listening to and playing music as do all teenage girls her age. She has a particular love of drama and acting and is starring in a forthcoming feature film called ‘Hunky Dory’ and had several parts in Welsh language programmes such as Pobol y Cwm and Gwaith Catref. -

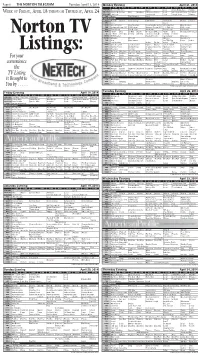

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Blue Plaques in Bromley

Blue Plaques in Bromley Blue Plaques in Bromley..................................................................................1 Alexander Muirhead (1848-1920) ....................................................................2 Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1889)...................................................3 Brass Crosby (1725-1793)...............................................................................4 Charles Keeping (1924-1988)..........................................................................5 Enid Blyton (1897-1968) ..................................................................................6 Ewan MacColl (1915-1989) .............................................................................7 Frank Bourne (1855-1945)...............................................................................8 Harold Bride (1890-1956) ................................................................................9 Heddle Nash (1895-1961)..............................................................................10 Little Tich (Harry Relph) (1867-1928).............................................................11 Lord Ted Willis (1918-1992)...........................................................................12 Prince Pyotr (Peter) Alekseyevich Kropotkin (1842-1921) .............................13 Richmal Crompton (1890-1969).....................................................................14 Sir Geraint Evans (1922-1992) ......................................................................15 Sir -

Investigating Format

Investigating Format Investigating Format: The Transferral and Translation of Televised Productions in Italy and England By Bronwen Hughes Investigating Format: The Transferral and Translation of Televised Productions in Italy and England By Bronwen Hughes This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Bronwen Hughes All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1689-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1689-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................. viii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Fictional Portrayals of the Police 1.1 A brief overview of televised police procedurals in the United Kingdom and in Italy 1.2 Presentation of ‘The Bill’ and ‘La Squadra’ 1.3 A comparative study of the non-dialogical features in ‘The Bill’ and ‘La Squadra’ Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 22 Research Framework: Talk in Institutional Settings 2.1 Conversation Analysis versus Critical Discourse