Rethinking Our Thinking About Asanas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

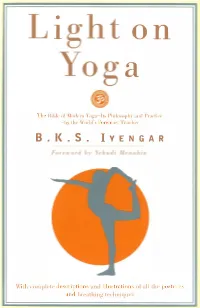

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

—The History of Hatha Yoga in America: The

“The History of Hatha Yoga in America: the Americanization of Yoga” Book proposal By Ira Israel Although many American yoga teachers invoke the putative legitimacy of the legacy of yoga as a 5000 year old Indian practice, the core of the yoga in America – the “asanas,” or positions – is only around 600 years old. And yoga as a codified 90 minute ritual or sequence is at most only 120 years old. During the period of the Vedas 5000 years ago, yoga consisted of groups of men chanting to the gods around a fire. Thousands of years later during the period of the Upanishads, that ritual of generating heat (“tapas”) became internalized through concentrated breathing and contrary or bipolar positions e.g., reaching the torso upwards while grounding the lower body downwards. The History of Yoga in America is relatively brief yet very complex and in fact, I will argue that what has happened to yoga in America is tantamount to comparing Starbucks to French café life: I call it “The Americanization of Yoga.” For centuries America, the melting pot, has usurped sundry traditions from various cultures; however, there is something unique about the rise of the influence of yoga and Eastern philosophy in America that make it worth analyzing. There are a few main schools of hatha yoga that have evolved in America: Sivananda, Iyengar, Astanga, and later Bikram, Power, and Anusara (the Kundalini lineage will not be addressed in this book because so much has been written about it already). After practicing many of these different “styles” or schools of hatha yoga in New York, North Carolina, Florida, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Paris as well as in Thailand and Indonesia, I became so fascinated by the history and evolution of yoga that I went to the University of California at Santa Barbara to get a Master of Arts Degree in Hinduism and Buddhism which I completed in 1999. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

Thriving in Healthcare: How Pranayama, Asana, and Dyana Can Transform Your Practice

Thriving in Healthcare: How pranayama, asana, and dyana can transform your practice Melissa Lea-Foster Rietz, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, RYT-200 Presbyterian Medical Services Farmington, NM [email protected] Professional Disclosure I have no personal or professional affiliation with any of the resources listed in this presentation, and will receive no monetary gain or professional advancement from this lecture. Talk Objectives Provide a VERY brief history of yoga Define three aspects of wellness: mental, physical, and social. Define pranayama, asana, and dyana. Discuss the current evidence demonstrating the impact of pranayama, asana, and dyana on mental, physical, and social wellness. Learn and practice three techniques of pranayama, asana, and dyana that can be used in the clinic setting with patients. Resources to encourage participation from patients and to enhance your own practice. Yoga as Medicine It is estimated that 21 million adults in the United States practice yoga. In the past 15 years the number of practitioners, of all ages, has doubled. It is thought that this increase is related to broader access, a growing body of research on the affects of the practice, and our understanding that ancient practices may hold the key to healing modern chronic diseases. Yoga: A VERY Brief History Yoga originated 5,000 or more years ago with the Indus Civilization Sanskrit is the language used in most Yogic scriptures and it is believed that the principles of the practice were transmitted by word of mouth for generations. Georg Feuerstien divides the history of Yoga into four catagories: Vedic Yoga: connected to ritual life, focus the inner mind in order to transcend the limitations of the ordinary mind Preclassical Yoga: Yogic texts, Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita Classical Yoga: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the eight fold path Postclassical Yoga: Creation of Hatha (willful/forceful) Yoga, incorporation of the body into the practice Modern Yoga Swami (master) Vivekananda speaks at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Exercise Yogasan

EXERCISE YOGASAN YOGA The word meaning of “Yoga” is an intimate union of human soul with God. Yoga is an art and takes into purview the mind, the body and the soul of the man in its aim of reaching Divinity. The body must be purified and strengthened through Ashtanga Yogas-Yama, Niyama, Asanas and Pranayama. The mind must be cleansed from all gross through Prathyaharam, Dharana, Dhyanam and Samadhi. Thus, the soul should turn inwards if a man should become a yogic adept. Knowledge purifies the mind and surrender takes the soul towards God. TYPE OF ASANAS The asanas are poses mainly for health and strength. There are innumerable asanas, but not all of them are really necessary, I shall deal with only such asanas as are useful in curing ailments and maintaining good health. ARDHA CHAKRSANA (HALF WHEEL POSTURE) This posture resembles half wheel in final position, so it’s called Ardha Chakrasana or half wheel posture. TADASANA (PALM TREE POSE) In Sanskrit ‘Tada’ means palm tree. In the final position of this posture, the body is steady like a Palm tree, so this posture called as ‘Tadasana’. BHUJANGAASANA The final position of this posture emulates the action of cobra raising itself just prior to striking at its prey, so it’s called cobra posture or Bhujangasan. PADMASANA ‘Padma’ means lotus, the final position of this posture looks like lotus, so it is called Padmasana. It is an ancient asana in yoga and is widely used for meditation. DHANURASANA (BOW POSTURE) Dhanur means ‘bow’, in the final position of this posture the body resembles a bow, so this posture called Dhanurasana or Bow posture. -

Yoga Federation of India ( Regd

YOGA FEDERATION OF INDIA ( REGD. UNDER THE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT. XXI OF 1860 REGD. NO.1195 DATED 14.02.90) RECOGNIZED BY INDIAN OLYMPIC ASSOCIATION - OCTOBER, 1998 TO FEBRUARY, 2011 Affiliated to Asian Yoga Federation, International Yoga Sports Federation & International Yoga Federation REGD. OFFICE: FLAT NO.501, GHS-93, SECTOR-20, PANCHKULA- 134116 (HARYANA), INDIA e-mail:[email protected], Mobile No.+91-94174-14741, Website:- www.yogafederationofindia.com SYLLABUS AND GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL/ZONAL/STATE/DISTRICT YOGASANA COMPETITION SUB JUNIOR GROUP–A (8-1110 YEARS, BOYS & GIRLS) 1. VRIKSHASANA 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 1. VRIKSHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. Back maximum stretched. 2. Arms touching the ear. 8. CHAKRASANA 3. Both hands folded above the 9. SARVANGASANA shoulders. 10. DHANURASANA 4. Gaze in front. 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 1. Hands on the side of feet 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 2. Legs should be straight 2. Forehead touching knees 2. Palms on the heels 3. Back maximum stretched 3. Palms on the heels from the side 3. Knees, heels and toes together 4. Chest & forehead touching the legs 4. Toes, heels and knees together 4. Ankles touching the ground 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. One Leg stretch with toe pointing upwards, gripping of toe with thumb and 1. Both arms in between thigh and calf. 1. Back, neck and head to be maximum index finger. 2. Ears to be covered by palms. straight. 2. Gripping of toe of other leg with thumb, 2. -

Intermediate Series (Nadi Shodana)

-1- -2- Ashtanga Yoga - © AshtangaYoga.info Ashtanga Yoga - © AshtangaYoga.info (EX) turn front (IN) grab left foot, head up (EX) Chaturanga Dandasana Intermediate Series 9 IN up 15 EX chin to shinbone 7 IN Urdhva Mukha Svanasana 10 EX Chaturanga Dandasana 5Br KROUNCHASANA 8 EX Adho Mukha Svanasana (Nadi Shodana) 11 IN Urdhva Mukha Svanasana 16 IN head up 9 IN jump, head up 12 EX Adho Mukha Svanasana (EX) hands to the floor 10 EX Uttanasana 13 IN jump, head up 17 IN up - IN come up For proper use: 14 EX Uttanasana 18 EX Chaturanga Dandasana (EX) Samasthitih • Vinyasas are numbered through from - IN come up 19 IN Urdhva Mukha Svanasana Samasthitih to Samasthitih, but only bold lines are practised. (EX) Samasthitih 20 EX Adho Mukha Svanasana BHEKASANA • The breathing to the Vinyasa is showed as 21 IN jump, head up VINYASA: 9 IN / EX. Every Vinyasa has one breath to lead and additional breaths printed in KROUNCHASANA 22 EX Uttanasana ASANA: 5 brackets. VINYASA: 22 - IN come up DRISTI: NASAGRAI • Above the Vinyasa count for a position the name of the Asana is given, with the ASANA: 8,15 (EX) Samasthitih 1 IN hands up number of Vinyasas from Samasthitih to DRISTI: PADHAYORAGRAI 2 EX Uttanasana Samasthitih, the number which represents the Asana, and the Dristi (= point of gaze). 1 IN hands up SALABHASANA 3 INININ head up 2 EX Uttanasana VINYASA: 9 4 EX Chaturanga Dandasana Further explanations: 3 IN head up ASANA: 5,6 5 IN lift feet AshtangaYoga.info 4 EX Chaturanga Dandasana DRISTI: NASAGRAI (EX) toes to the ground PASASANA 5 IN Urdhva Mukha -

What Is Power Yoga?

WHAT IS POWER YOGA? Power Yoga is a vigorous, fitness-based approach to Vinyasa-style yoga; its combination of physicality, strength, and flexibility, make for a customizable and athletic yoga workout. The practice of Power Yoga is perfect for anyone looking to combine physical fitness with intuitive spiritual self-discovery. Benefits MENTAL • Sharpens Concentration & Self-Discipline PHYSICAL • Reduces Stress SPIRITUAL • Aids Meditation, Focus & Clarity • Synchronizes Breath • Improves Circulation & Body • Enhances Posture & Balance • Cultivates Self-Awareness • Increases Strength & Flexibility • Unlocks Individual Power • Promotes Stamina & Weight Loss & Energy History Srivasta Ramaswami, the last living student in the K. Pattabhi Jois, Magaña Baptiste, US of the legendary yogi, begins his yoga studies in studies with Indra Devi The first Western students, Shri T. Krishnamachrya, Mysore, India, with in Los Angeles and two including Americans, David continues to teach the Shri T. Krishnamacharya, years later she and her Williams and Norman Allen, “Vinyasa Kramer Yoga the inspiration and founder husband open the first begin studying Ashtanga yoga Institute” at Loyola behind yoga practiced in yoga studio in San in Mysore, facilitating its spread Marymount University the United States today. Francisco. westward. in Los Angeles. 1927 Early 1950’s Early 1970’s Today Power Yoga has gained in popularity, with both local studios and national chains, offering various forms of a heated, full body athletic practice. 1938 1962 1990’s Power Yoga Emerges Indra Devi, K. Pattabhi Jois, Larry Schultz, Trained by Williams and Baron Baptiste, considered the mother publishes his treatise who studied Ashtanga yoga Allen, Bryan Kest in Los the son on Magaña Baptiste of western yoga, on Ashtanga Yoga, with K. -

Inverted Bow (Or Wheel) Poses, and Variations Anuvittasana

URDHVA DHANURASANA Anuvittasana Chakrasana Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana Parivrtta Urdhva Dhanurasana Inverted Bow (or Wheel) Poses, and Salamba Urdhva Dhanurasana Trianga Mukhottanasana Urdhva Dhanurasana Variations You tell me! Viparita padangushtha Click here for Dandasana. shirasparshasana Click here for Dhanurasana. The Sanskrit word "dhanur" means bow-shaped, curved or bent. The bow referred is a bow as in "bow and arrow." This asana is so named because the body mimics the shape of a bow with its string stretched back ready to shoot an arrow. Top (and this page's index) Anuvittasana The Asana Index Home Join the Yoga on the Mid- Standing Backbend Atlantic List Anuvittasana Demonstrated by David Figueroa Yogi Unknown ©OM yoga center Photograph by Adam Dawe Cindy Lee, Director (eMail me if you know the Yogi's 135 West 14th street, 2nd Floor name!) New York, NY 10011 Tel: 212-229-0267 Eka Pada Urdhva Top (and this page's Dhanurasana index) The Asana Index Home Join the Yoga on the Mid- One-Legged Inverted Bow (or Atlantic List Wheel) Pose Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana Step One Demonstrated by Susan "Lippy" Orem ©OM yoga center Cindy Lee, Director 135 West 14th street, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10011 Tel: 212-229-0267 Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana Full Version Demonstrated by Simon Borg-Olivier Yoga Synergy P.O. Box 9 Waverley 2024 Australia Tel. (61 2) 9389 7399 Salamba Urdhva Top (and this page's Dhanurasana index) The Asana Index Home Join the Yoga on the Mid- Supported, Inverted Bow (or Atlantic List Wheel) Salamba Urdhva Dhanurasana Demonstrated by Mark Bouckoms Hatha Yoga Centre 42 Nayland St. -

Yoga Teacher Training – House of Om

LIVE LOVE INSPIRE HOUSE OF OM MODULE 8 PRACTICE 120 MINS In this Vinyasa Flow we train all the poses of the Warrior series, getting ready to take our training from the physical to beyond HISTORY 60 MINS Yoga has continued evolving and expanding throughout the time that’s why until nowadays it is still alive thanks to these masters that dedicated their life in order to practice and share their knowledge with the world. YOGA NIDRA ROUTINE Also known as Yogic sleep, Yoga Nidra is a state of consciousness between waking and sleeping. Usually induced by a guided meditation HISTORY QUIZ AND QUESTIONS 60 MINS Five closed and two open question will both entertain with a little challenge, and pinpoint what resonated the most with your individual self. REFLECTION 60 MINS Every module you will be writing a reflection. Save it to your own journal as well - you will not only learn much faster, but understand what works for you better. BONUS Mahamrityumjaya Mantra In all spiritual traditions, Mantra Yoga or Meditation is regarded as one of the safest, easiest, and best means of systematically overhauling the patterns of consciousness. HISTORY YOGA HISTORY. MODERN PERIOD Yoga has continued evolving and expanding throughout the time that’s why until nowadays it is still alive thanks to these masters that dedicated their life in order to practice and share their knowledge with the world. In between the classical yoga of Patanjali and the 20th century, Hatha Yoga has seen a revival. Luminaries such as Matsyendranath and Gorakhnath founded the Hatha Yoga lineage of exploration of one’s body-mind to attain Samadhi and liberation. -

• Principles of Dynamic Mindfulness

1st Module EARTH Philosophy, History, Anatomy and the Subtle Body We start by diving into the history and philosophy of Yoga and Buddhism, in order to find out how are these ancient teachings and practices relevant in the context of our contemporary lives. We will put the teachings into practice through a lab sequence and an introduction to meditation. These will be complemented by a thorough exploration of the anatomy of the physical and energetic bodies. By the time you complete Module 1, your yoga practice will feel far more comprehensive and supported by the knowledge and techniques you have learned. You will be ready to approach teaching with wisdom and grounded confidence. Module 1 is also an incredible experience for those wanting to explore their own practice on a new level, even if you do not intend to become a teacher. • Opening: Perspectives on the Body: East/West • History & Evolution of Yoga • Introduction to Yoga Philosophy: Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras • What did Buddha teach ? • Applied Buddhist Psychology • Chinese Spiritual Heritage • Anatomy for Yoga Teachers • Subtle Body Anatomy • Principles of Dynamic Mindfulness • Introduction to Meditation • Sequence Lab • Western Somatics – Practices of Embodiment 2nd Module WATER Basic Asanas, Alignment & Adjustments The second module builds on the knowledge of anatomy and the subtle body from Module 1 and expands into sequencing a dynamic and intelligent class based on your knowledge of how the asanas and the body function together. You will learn a comprehensive list of yoga asanas (poses), healthy alignment and safe, helpful adjustments. By the end of Segment 2 you will be able to teach your fellow trainees a simple, challenging and effective yoga class with a focus on breath, sequencing and alignment.