Thinking in Forest Time a Strategy for the Massachusetts Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Township Newsletter

THE NEWSLETTER OF SOUTH MIDDLETON TOWNSHIP Summer TALK of the 2021 TOWNship A few weeks ago, I released the “State of the Township” With more people comes pressures and increased demand report (found on the Township’s website) which goes into not only on public services (i.e. roads, schools, hospitals, etc.) greater detail on many of the items I will discuss here. In es- but also an obvious question – where are these people going sence, despite COVID-19 knocking us around about a bit, the to live? Since 2013, population growth in Cumberland County state of the Township is quite strong, and we are continually has exceeded available housing stock and has remained high. progressing towards a bright future of growth and prosperity. This in itself may not necessarily be cause for alarm, if vacancy In addition, many of the projects we are working on for this rates remain at a healthy point to provide selection it offers year are covered elsewhere in this Newsletter. enough choices to keep cost of living down. Unfortunately, The Board of Supervisors is committed to ensuring the vacancy rates in South Middleton for single-family homes is most effective and efficient delivery of public services while almost zero. When there is high-demand, basic economics being good stewards of your tax money. For instance, South sees prices go up, and it has in South Middleton, by about 30 Middleton’s overall tax rate is lower than 39 percent of all percent. This creates a two-pronged effect: it leads to more similar-sized communities. -

Class Listing

Tanbark Cavalcade Of Roses Cheryl Rangel - Secretary 1101 Peace Dr Wheeling, IL 60090 (847) 537-4743 Class Listing Class Description Place Nbr Horse Shown By Owner 001 ASB Fine Harness - Open 1 194 Oh So What Penelope Weyenberg Penelope Weyenberg 002 ASB Show Pleasure - Driving ASHA Junior Exhibitor Challenge 1 202 Majestic's Aristotle Patrick Weiler A.Weiler Amy's Acres Show Horses LLC 003 Morgan Hunter Pleasure - Open No Entries 004 Exhibition - Open Western Bridle Path 1 116 Ch Harlem's Hot Prince Mary Strohfus Mary Strohfus 2 223 Just Give Me A Reason Kim Gallenberg Kim & Dennis Gallenberg 3 252 Walterway's Kickin' Assets Sondra Loos Mike/Jennifer Elnicky 005 ASB Country Pleasure Three Gaited - 17/Under 1 288 Bella La Donna Madison Mulligan Michelle Mulligan 2 211 Dreamacres Fleetwood Mac Jordan DeRoos Jordan DeRoos 3 241 Santa Fe Son Ava Girton Richard Equine Development 4 276 Paper Heiress JJW Collin Wood Jay & Jean Wood 5 170 Warrior's Sunbird Gillian Stanley Donita Christiansen 6 237 Ciao! Bello Mio Annie Ayotte Amy Ayotte 7 228 Clever Trevor Kylie Anderson Kylie Anderson 006 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure - Walk/Trot 10/Under 1 107 Ch Pierre Cardin Nina Hendersen La Fleur Stables 2 102 Champagne On Phire Brady Kasper Greenfield Farm 007 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure 18-38 1 270 Beau & Heirrow Avis Van Zomeren Mark/Renae Van Zomeren 2 258 Nutcracker's Odyssey Lindsey Swanson Lindsey Swanson 3 251 Hotze K. Sarah Etzold Sarah Etzold 4 221 Highpoint's Currency Katie Sheets Bob Jensen Stables Inc. 5 287 Inheiritance WAF Grace Famestead Grace Famestead 008 Hackney Show Pleasure Pony - Driving 1 264 Buckle Up HS Veronica Lindstrom Doug/Veronica Lindstrom 2 261 Finnagan Winnagan Audra Brizgys Christine Johnson 009 Morgan Classic Pleasure - Driving 1 139 Sarde's Soul Sister Kim Loewer Kim Loewer 010 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure - Walk/Trot 11/Over 1 266 PO's Nicolite Brooke Whitney R.Sperl/S. -

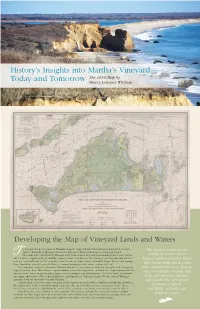

History's Insights Into Martha's Vineyard — Today and Tomorrow

History’s Insights into Martha’s Vineyard — The 1850 Map by Today and Tomorrow Henry Laurens Whiting Developing the Map of Vineyard Lands and Waters o develop this new version of Whiting’s map we extracted the Vineyard from a larger U.S. Coastal The greatest historical and Survey chart—From Muskeget Channel to Buzzard’s Bay and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. The lands were surveyed by Whiting’s crew from 1844 to 1852 and surrounding waters from 1845 to ecological treasure lies in 1857. A worn original of the beautifully engraved chart is archived in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum but for a features seldom recorded: fence year we searched fruitlessly for a pristine chart to scan. A chance visit to naturalist Nancy Weaver and mariner Dave Dandridge revealed a nearly flawless original hanging in their home on Lagoon Pond. lines (stone walls and wooden The map was scanned at Harvard’s Widener Library at a resolution of 1000 dots per inch and enlarged to rails), natural land cover (forests, display the fine detail. We inserted original elements from the larger chart: attribution to Superintendent Bache; other woodlands, swamps, and distance scale; notes on survey dates, buoys, coastal dangers, and abbreviations; No Man’s Land; a locational inset map; and views of West Chop Lighthouse and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. We also added Whiting’s fresh and saltwater marshes), signature from his surveyor’s log and a legend. and remarkably, farm details Careful study reveals the map’s stunning detail: bathymetry in feet where shallow and fathoms elsewhere; the composition of the sea-bottom (mud, sand, etc.); the speed of tidal currents; and major shoals. -

Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts By

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts by David Foster, David Kittredge, Brian Donahue, Glenn Motzkin, David Orwig, Aaron Ellison, Brian Hall, Betsy Colburn and Anthony D’Amato A group of nine ecologists and historians affiliated with the Harvard Forest recently published a report on the status and future of forestlands in Massachusetts. Based on their assessment of the changing landscape, they developed a vision to protect the Commonwealth’s forests and the important economic, recreation, habitat and ecosystem services they provide. What follows is a summary of their report, “Wildlands and Woodlands: A Vision for the Forests of Massachusetts”. Massachusetts offers an unusual and urgent opportunity for forest conservation. Following widespread agricultural decline in the 19th century, the landscape reforested naturally and currently supports a wide expanse of maturing forest. Despite its large population, the state has more natural vegetation today than at nearly any time in the last three centuries. With its extensive forests supporting ecosystem processes, thriving wildlife populations, and critical environmental services for society, there is a great need to protect this landscape for the future. However, this historic window of opportunity is closing as forests face relentless development pressure. After decades of forest protection by state agencies and private organizations, patterns of land conservation and forest management are still inadequate to meet future societal and environmental needs. Large areas of protected forestland are uncommon, conserved forests are largely disconnected, important natural and cultural resources (including many plant and animal species) are vulnerable to loss, logging is often poorly planned and managed, and old-growth forests and reserves isolated from human impact are rare. -

The Ecosystems Center Report 2005 the MBL Founded the Ecosystems Center As a Year-Round Research Program in 1975

The Ecosystems Center Report 2005 The MBL founded the Ecosystems Center as a year-round research program in 1975. The center’s mission is to investigate the structure and functioning of ecological systems, predict their response to changing environmental conditions, apply the resulting knowledge to the preservation and management of natural resources, and educate both future scientists and concerned citizens. In Brazil, scientists investigate how the clearing of tropical forests in the western Amazon changes greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide released into the atmosphere. What will the effect be on global climate? How will change in temperature and atmospheric gas concentrations affect the productivity of forests? What effect does the clearing of forest for pasture have on tropical streams ecosystems? In Boston Harbor, researchers measure the transfer of nitrogen from the sediments to the water column. How long will it take the harbor to recover from decades of sewage addition? In the Arctic rivers of Eurasia, center scientists have conducted research that Ecosystems Center shows increased freshwater discharge to researchers add low the Arctic Ocean. If ocean circulation is levels of fertilizer to the incoming tide in creeks in The Ecosystems Center operates as a affected, how might the climate in western the Plum Island Estuary in collegial association of scientists under Europe and eastern North America change? northern Massachusetts. the leadership of John Hobbie and Jerry They are examining the response of the Melillo. Center scientists work together On Martha’s Vineyard, researchers surrounding salt marsh on projects, as well as with investigators restore coastal sandplain ecosystems with to increased levels of nutrients caused by from other MBL centers and other either controlled burning or mechanical land-use change. -

V. Insights from Time and the Land

Insights from a Natural and Cultural Landscape V. Insights from Time and the Land Pre-History Section Ecology and conservation lessons • Template for spatial variation - gradual boundaries driven by landscape variation - soils, moisture; significant island-wide variation. • Natural processes dominate; change is slow with few notable exceptions • Vegetation structure and species missing from present. Old growth - pine, hardwoods, and mixed forest. Forest dynamics structure - old trees, CWD, damaged trees, uproots. More beech, beetlebung and hickory; very little open land or successional habitat. • People with an abundance of natural resources; highly adaptable. Accommodate growth and humans; preserve, sustain nature intact. Real distinction: passive vs active management; wildland vs woodland. All is cultural but humans can make real difference in decisions. Viable alternative is to allow natural processes to shape and reassert themselves. E.g., cord wood and timber versus old-growth; salvage or no; fire versus sheep versus succession; coastal pond - natural breach vs excavator. Topics Inertia - what happens today is very dependent on the past, may be contingent on our expectation for the future. What we do, what natural forces operate on, are conditions handed to us from history; but the entire system is in motion-erosion of features created in the past; plants and animals recovering from historical changes. Even if we do nothing much will change. Without future changes in the system - i.e. environmental change. If change occurs; inertia will condition the response - e.g. coastal erosion, shift in species. To keep things the way they are - is impossible - but even to approximate, requires huge effort. World without us, 19th C New England. -

Agroforestry News Index Vol 1 to Vol 22 No 2

Agroforestry News Index Vol 1 to Vol 22 No 2 2 A.R.T. nursery ..... Vol 2, No 4, page 2 Acorns, edible from oaks ..... Vol 5, No 4, page 3 Aaron, J R & Richards: British woodland produce (book review) ..... Acorns, harvesting ..... Vol 5, No 4, Vol 1, No 4, page 34 page 3 Abies balsamea ..... Vol 8, No 2, page Acorns, nutritional composition ..... 31 Vol 5, No 4, page 4 Abies sibirica ..... Vol 8, No 2, page 31 Acorns, removing tannins from ..... Vol 5, No 4, page 4 Abies species ..... Vol 19, No 1, page 13 Acorns, shelling ..... Vol 5, No 4, page 3 Acca sellowiana ..... Vol 9, No 3, page 4 Acorns, utilisation ..... Vol 5, No 4, page 4 Acer macrophyllum ..... Vol 16, No 2, page 6 Acorus calamus ..... Vol 8, No 4, page 6 Acer pseudoplatanus ..... Vol 3, No 1, page 3 Actinidia arguta ..... Vol 1, No 4, page 10 Acer saccharum ..... Vol 16, No 1, page 3 Actinidia arguta, cultivars ..... Vol 1, No 4, page 14 Acer saccharum - strawberry agroforestry system ..... Vol 8, No 1, Actinidia arguta, description ..... Vol page 2 1, No 4, page 10 Acer species, with edible saps ..... Vol Actinidia arguta, drawings ..... Vol 1, 2, No 3, page 26 No 4, page 15 Achillea millefolium ..... Vol 8, No 4, Actinidia arguta, feeding & irrigaton page 5 ..... Vol 1, No 4, page 11 3 Actinidia arguta, fruiting ..... Vol 1, Actinidia spp ..... Vol 5, No 1, page 18 No 4, page 13 Actinorhizal plants ..... Vol 3, No 3, Actinidia arguta, nurseries page 30 supplying ..... Vol 1, No 4, page 16 Acworth, J M: The potential for farm Actinidia arguta, pests and diseases forestry, agroforestry and novel tree .... -

The Commercial Utilization of Tanbark Oak and Western White Oak in Oregon

The Commercial Utilization of Tanbark Oak and Western White Oak in Oregon by Ralph Dempsey /d\ A Thesis 7 1958 Presented to the Faculty ( of the School of Forestry Ore'on State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science March 1938 Approved: rofessor 0± forestry INTRODUCTION Tanbark oak, Lithocarpus densiflora (Hooker and Arnott) Rehder, and Oregon white oak (uercus arryana Hooker) are Oreon's most potentially valuable hardwoods. These trees are comparatively well known, but they have received little commercial attention. The people engac'ec9 in the manu- facture cf leather have used the bark of Tanbark oak he- cause it produces a considerable quantity of hirh rad.e tannin. The tree, which has previously been left to rot after the bark had been peeled, could in some way be uti- lized. The Oregon white oak has been used chiefly as fuel. Its uses in other fields has gradually deceased until it is now little used except for firewood. The wood of these species have received little consideration and their possi- bilities are unknown. This study was made for the purpose of reviewing the previous uses of these woods, and with the advent of new methods of kiln drying, to find a solution to a more efficient utilization. The main objections to the use of these woods have been their severe warping sn cheek- ing in seasoning. The results of j:revious studies, and experimental work bein carried on by the Forest Products Laboratory, indicates these woods can be successfully kiln dried. It is hoped that this will give these western oaks a place in the lumber markets of the nation, and there- by lead to a more efficient utilization of these woods. -

The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation

Articles The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation DAVID FOSTER, FREDERICK SWANSON, JOHN ABER, INGRID BURKE, NICHOLAS BROKAW, DAVID TILMAN, AND ALAN KNAPP Recognition of the importance of land-use history and its legacies in most ecological systems has been a major factor driving the recent focus on human activity as a legitimate and essential subject of environmental science. Ecologists, conservationists, and natural resource policymakers now recognize that the legacies of land-use activities continue to influence ecosystem structure and function for decades or centuries—or even longer— after those activities have ceased. Consequently, recognition of these historical legacies adds explanatory power to our understanding of modern conditions at scales from organisms to the globe and reduces missteps in anticipating or managing for future conditions. As a result, environmental history emerges as an integral part of ecological science and conservation planning. By considering diverse ecological phenomena, ranging from biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles to ecosystem resilience to anthropogenic stress, and by examining terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in tem- perate to tropical biomes, this article demonstrates the ubiquity and importance of land-use legacies to environmental science and management. Keywords: land use, disturbance, conservation, ecosystem process, natural resource management n the mid-1980s two groups met independently, at natural resource management, have come to recognize that Ithe tropical Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico and site history is embedded in the structure and function of all at the temperate Harvard Forest in New England, to draft pro- ecosystems, that environmental history is an integral part of posals for a competition to qualify for the National Science ecological science, and that historical perspectives inform Foundation’s (NSF) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) policy development and the management of systems ranging program. -

Non-Wood Forest Products in Asiaasia

RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/281994/28 Non-Wood Forest Products in AsiaAsia REGIONAL OFFICE FORFOR ASIAASIA AND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA)(RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THE UNITED NATIONS BANGKOK 1994 RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/28 1994/28 Non-Wood ForestForest Products in AsiaAsia EDITORS Patrick B. Durst Ward UlrichUlrich M. KashioKashio REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIAASIA ANDAND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTUREAGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THETHE UNITED NTIONSNTIONS BANGKOK 19941994 The designationsdesignations andand the presentationpresentation ofof material in thisthis publication dodo not implyimply thethe expressionexpression ofof anyany opinionopinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country,country, territory, citycity or areaarea oror ofof its its authorities,authorities, oror concerningconcerning thethe delimitation of its frontiersfrontiers oror boundaries.boundaries. The opinionsopinions expressed in this publicationpublication are those of thethe authors alone and do not implyimply any opinionopinion whatsoever on the part ofof FAO.FAO. COVER PHOTO CREDIT: Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph PHOTO CREDITS:CREDITS: Pages 8,8, 17,72,80:17, 72, 80: Mr.Mr. MohammadMohammad Iqbal SialSial Page 18: Mr. A.L. Rao Pages 54, 65, 116, 126: Mr.Mr. Urbito OndeoOncleo Pages 95, 148, 160: Mr.Mr. Michael Jensen Page 122: Mr.Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph EDITED BY:BY: Mr. Patrick B. Durst Mr. WardWard UlrichUlrich Mr. M. KashioKashio TYPE SETTINGSETTING AND LAYOUT OF PUBLICATION: Helene Praneet Guna-TilakaGuna-Tilaka FOR COPIESCOPIES WRITE TO:TO: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the PacificPacific 39 Phra AtitAtit RoadRoad Bangkok 1020010200 FOREWORD Non-wood forest productsproducts (NWFPs)(NWFPs) havehave beenbeen vitallyvitally importantimportant toto forest-dwellersforest-dwellers andand rural communitiescommunities forfor centuries.centuries. -

Integrated Studies of the Drivers, Dynamics and Consequences of Landscape Change in New England

INTEGRATED STUDIES OF THE DRIVERS, DYNAMICS AND CONSEQUENCES OF LANDSCAPE CHANGE IN NEW ENGLAND HARVARD FOREST LTER-IV 2006 - 2012 David R. Foster, Principal Investigator Harvard Forest, Harvard University Co-Investigators Emery R. Boose Elizabeth A. Colburn Aaron M. Ellison Julian L. Hadley Glenn Motzkin John F. O'Keefe Harvard Forest, Harvard University David A. Orwig W. Wyatt Oswald Julie Pallant Kristina A. Stinson J. William Munger Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University Steven C. Wofsy Earth and Planetary Science, Harvard University Kathleen Donohue Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Paul R. Moorcroft Jerry M. Melillo Marine Biological Laboratory Paul A. Steudler Elizabeth S. Chilton University of Massachusetts David A. Kittredge, Jr. Eric A. Davidson Woods Hole Research Center Serita D. Frey Erik A. Hobbie University of New Hampshire Scott V. Ollinger Brian Donahue Brandeis University Knute J. Nadelhoffer University of Michigan Harvard Forest LTER IV – Project Summary The Harvard Forest (HFR) LTER is an integrated program investigating forest response to natural and human disturbance and environmental change over broad spatial and temporal scales. Involving >25 researchers, 150 undergraduate and graduate students, and a dozen institutions, HFR LTER embraces the biological, physical, and social sciences to address fundamental and applied questions for dynamic ecosystems. Our work on the ecological effects of the primary drivers of forest change in New England (Human Impacts, Natural Disturbances, -

Forest Plans of North America

Forest Plans of North America Edited by Jacek P. Siry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Pete Bettinger Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Krista Merry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Donald L. Grebner Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, USA Kevin Boston Department of Forest Engineering, Resources and Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA Christopher Cieszewski Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 32 Jamestown Road, London NW1 7BY, UK 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).