V. Insights from Time and the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![About Pigs [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0911/about-pigs-pdf-50911.webp)

About Pigs [PDF]

May 2015 About Pigs Pigs are highly intelligent, social animals, displaying elaborate maternal, communicative, and affiliative behavior. Wild and feral pigs inhabit wide tracts of the southern and mid-western United States, where they thrive in a variety of habitats. They form matriarchal social groups, sleep in communal nests, and maintain close family bonds into adulthood. Science has helped shed light on the depths of the remarkable cognitive abilities of pigs, and fosters a greater appreciation for these often maligned and misunderstood animals. Background Pigs—also called swine or hogs—belong to the Suidae family1 and along with cattle, sheep, goats, camels, deer, giraffes, and hippopotamuses, are part of the order Artiodactyla, or even-toed ungulates.2 Domesticated pigs are descendants of the wild boar (Sus scrofa),3,4 which originally ranged through North Africa, Asia and Europe.5 Pigs were first domesticated approximately 9,000 years ago.6 The wild boar became extinct in Britain in the 17th century as a result of hunting and habitat destruction, but they have since been reintroduced.7,8 Feral pigs (domesticated animals who have returned to a wild state) are now found worldwide in temperate and tropical regions such as Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia and on island nations, 9 such as Hawaii.10 True wild pigs are not native to the New World.11 When Christopher Columbus landed in Cuba in 1493, he brought the first domestic pigs—pigs who subsequently spread throughout the Spanish West Indies (Caribbean).12 In 1539, Spanish explorers brought pigs to the mainland when they settled in Florida. -

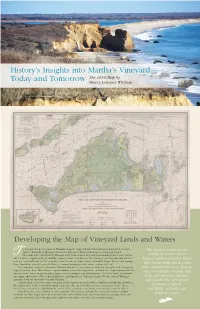

History's Insights Into Martha's Vineyard — Today and Tomorrow

History’s Insights into Martha’s Vineyard — The 1850 Map by Today and Tomorrow Henry Laurens Whiting Developing the Map of Vineyard Lands and Waters o develop this new version of Whiting’s map we extracted the Vineyard from a larger U.S. Coastal The greatest historical and Survey chart—From Muskeget Channel to Buzzard’s Bay and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. The lands were surveyed by Whiting’s crew from 1844 to 1852 and surrounding waters from 1845 to ecological treasure lies in 1857. A worn original of the beautifully engraved chart is archived in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum but for a features seldom recorded: fence year we searched fruitlessly for a pristine chart to scan. A chance visit to naturalist Nancy Weaver and mariner Dave Dandridge revealed a nearly flawless original hanging in their home on Lagoon Pond. lines (stone walls and wooden The map was scanned at Harvard’s Widener Library at a resolution of 1000 dots per inch and enlarged to rails), natural land cover (forests, display the fine detail. We inserted original elements from the larger chart: attribution to Superintendent Bache; other woodlands, swamps, and distance scale; notes on survey dates, buoys, coastal dangers, and abbreviations; No Man’s Land; a locational inset map; and views of West Chop Lighthouse and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. We also added Whiting’s fresh and saltwater marshes), signature from his surveyor’s log and a legend. and remarkably, farm details Careful study reveals the map’s stunning detail: bathymetry in feet where shallow and fathoms elsewhere; the composition of the sea-bottom (mud, sand, etc.); the speed of tidal currents; and major shoals. -

The Development of Woodland Ownership in Denmark C

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2007 A Windfall for the Magnates: The evelopmeD nt of Woodland Ownership in Denmark Eric Kades William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Kades, Eric, "A Windfall for the Magnates: The eD velopment of Woodland Ownership in Denmark" (2007). Faculty Publications. 196. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/196 Copyright c 2007 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs Book Reviews 223 Bo Fritzb0ger, A Windfall for the Magnates: The Development of Woodland Ownership in Denmark c. 1150-1830, Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2004. Pp. 432. $50.00 (ISBN 8-778-38936-4 ). Property rights imply scarcity. In proverbial states of nature the forest is vast and salted only lightly with humans, and hence it is a commons. Every natural forest was once such an unclaimed wilderness. The early dates at which teeming human populations produced conditions of scarcity, however, is surprising. Bo Fritzboger's A Windfall for the Magnates traces in extraordinary detail the Danish legal and social responses to deforestation. Disputes over forest resources in Europe arose around AD 900 at the latest. Fritzboger provides unambiguous evidence that Denmark experienced wood short- 224 Law and History Review, Spring 2007 ages by 1200, with deforestation accelerating over the next six hundred years. The Danish responses were typical of Europe: the privatization of common ownership ("enclosure"), and the enactment of statutes mandating preservation of woodlands. -

'Common Rights' - What Are They?

'Common Rights' - What are they? An investigation into rights of passage and rights of land use (or rights of common) Alan Shelley PG Dissertation in Landscape Architecture Cheltenham & Gloucester College of Higher Education April2000 Abstract There is a level of confusion relating to the expression 'common' when describing 'common rights'. What is 'common'? Common is a word which describes sharing or 'that affecting all alike'. Our 'common humanity' may be a term used to describe people in general. When we refer to something 'common' we are often saying, or implying, it is 'ordinary' or as normal. Mankind, in its earliest civilisation formed societies, usually of a family tribe, that expanded. Society is principled on community. What are 'rights'? Rights are generally agreed practices. Most often they are considered ethically, to be moral, just, correct and true. They may even be perceived, in some cases, to include duty. The evolution of mankind and society has its origins in the land. Generally speaking common rights have come from land-lore (the use of land). Conflicts have evolved between customs and the statutory rights of common people (the people of the commons). This has been influenced by Church (Canonical) law, from Roman formation, statutory enclosures of land and the corporation of local government. Privilege, has allowed 'freemen', by various customs, certain advantages over the general populace, or 'common people'. Unfortunately, the term no longer describes a relationship of such people with the land, but to their nationhood. Contents Page Common Rights - What are they?................................................................................ 1 Rights of Common ...................................................................................................... 4 Woods and wood pasture ............................................................................................ -

Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts By

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts by David Foster, David Kittredge, Brian Donahue, Glenn Motzkin, David Orwig, Aaron Ellison, Brian Hall, Betsy Colburn and Anthony D’Amato A group of nine ecologists and historians affiliated with the Harvard Forest recently published a report on the status and future of forestlands in Massachusetts. Based on their assessment of the changing landscape, they developed a vision to protect the Commonwealth’s forests and the important economic, recreation, habitat and ecosystem services they provide. What follows is a summary of their report, “Wildlands and Woodlands: A Vision for the Forests of Massachusetts”. Massachusetts offers an unusual and urgent opportunity for forest conservation. Following widespread agricultural decline in the 19th century, the landscape reforested naturally and currently supports a wide expanse of maturing forest. Despite its large population, the state has more natural vegetation today than at nearly any time in the last three centuries. With its extensive forests supporting ecosystem processes, thriving wildlife populations, and critical environmental services for society, there is a great need to protect this landscape for the future. However, this historic window of opportunity is closing as forests face relentless development pressure. After decades of forest protection by state agencies and private organizations, patterns of land conservation and forest management are still inadequate to meet future societal and environmental needs. Large areas of protected forestland are uncommon, conserved forests are largely disconnected, important natural and cultural resources (including many plant and animal species) are vulnerable to loss, logging is often poorly planned and managed, and old-growth forests and reserves isolated from human impact are rare. -

The Ecosystems Center Report 2005 the MBL Founded the Ecosystems Center As a Year-Round Research Program in 1975

The Ecosystems Center Report 2005 The MBL founded the Ecosystems Center as a year-round research program in 1975. The center’s mission is to investigate the structure and functioning of ecological systems, predict their response to changing environmental conditions, apply the resulting knowledge to the preservation and management of natural resources, and educate both future scientists and concerned citizens. In Brazil, scientists investigate how the clearing of tropical forests in the western Amazon changes greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide released into the atmosphere. What will the effect be on global climate? How will change in temperature and atmospheric gas concentrations affect the productivity of forests? What effect does the clearing of forest for pasture have on tropical streams ecosystems? In Boston Harbor, researchers measure the transfer of nitrogen from the sediments to the water column. How long will it take the harbor to recover from decades of sewage addition? In the Arctic rivers of Eurasia, center scientists have conducted research that Ecosystems Center shows increased freshwater discharge to researchers add low the Arctic Ocean. If ocean circulation is levels of fertilizer to the incoming tide in creeks in The Ecosystems Center operates as a affected, how might the climate in western the Plum Island Estuary in collegial association of scientists under Europe and eastern North America change? northern Massachusetts. the leadership of John Hobbie and Jerry They are examining the response of the Melillo. Center scientists work together On Martha’s Vineyard, researchers surrounding salt marsh on projects, as well as with investigators restore coastal sandplain ecosystems with to increased levels of nutrients caused by from other MBL centers and other either controlled burning or mechanical land-use change. -

Place-Names and Early Settlement in Kent

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society PLACE-NAMES AND EARLY SETTLEMENT IN KENT By P. H. REANEY, LITT.D., PH.D., F.S.A.1 APART from a few river-names like Medway and Limen and the names of such Romano-British towns as Rochester, Reculver and Richborough, the place-names of Kent are of English origin. What Celtic names survive are too few to throw any light on the history of Romano- British Kent. The followers and descendants of Hengest and Horsa gave names of their own to the places where they settled and the early settlement with which we are concerned is that which began with the coming of the Saxons in the middle of the fifth century A.D. The material for the history of this conquest is late and unsatisfac- tory, based entirely on legends and traditions. The earliest of our authorities, Gildas, writing a full century after the events, was concerned chiefly with castigating the Britons for their sins; names and dates were no concern of his. Bede was a writer of a different type, a historian on whom we can rely, but his Ecclesiastical History dates from about 730, nearly 300 years after the advent of the Saxons. He was a North- umbrian, too, and was careful to say that the story of Hengest was only a tradition, "what men say ". The problems of the Anglo-Saxon, Chronicle are too complicated to discuss in detail. It consists of a series of annals, with dates and brief lists of events. -

The Case of Cloud Computing Primavera De Filippi, Miguel Vieira

Information Commons between Peer-Production and Commodification: the case of Cloud Computing Primavera de Filippi, Miguel Vieira To cite this version: Primavera de Filippi, Miguel Vieira. Information Commons between Peer-Production and Commodi- fication: the case of Cloud Computing. 17th Annual Conference of The International Society forNew Institutional Economics, Jun 2013, Florence, Italy. hal-01382004 HAL Id: hal-01382004 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382004 Submitted on 15 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Information Commons between PeerProduction and Commodification: the case of Cloud Computing Primavera De Filippi1 Miguel Said Vieira2 Abstract Internet and digital technologies allowed for the emergence of new modes of production involving cooperation and collaboration amongst peers (peerproduction) and oriented towards the maximization of the common good—as opposed to the maximization of profits. To ensure that content will always remain available to the public, the output of production is often released under a specific regime that prevents anyone from subsequently turning it into a commodity (the regime of information commons). While this might reduce the likelihood of commodification, information commons can nonetheless be exploited by the market economy. -

The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation

Articles The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation DAVID FOSTER, FREDERICK SWANSON, JOHN ABER, INGRID BURKE, NICHOLAS BROKAW, DAVID TILMAN, AND ALAN KNAPP Recognition of the importance of land-use history and its legacies in most ecological systems has been a major factor driving the recent focus on human activity as a legitimate and essential subject of environmental science. Ecologists, conservationists, and natural resource policymakers now recognize that the legacies of land-use activities continue to influence ecosystem structure and function for decades or centuries—or even longer— after those activities have ceased. Consequently, recognition of these historical legacies adds explanatory power to our understanding of modern conditions at scales from organisms to the globe and reduces missteps in anticipating or managing for future conditions. As a result, environmental history emerges as an integral part of ecological science and conservation planning. By considering diverse ecological phenomena, ranging from biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles to ecosystem resilience to anthropogenic stress, and by examining terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in tem- perate to tropical biomes, this article demonstrates the ubiquity and importance of land-use legacies to environmental science and management. Keywords: land use, disturbance, conservation, ecosystem process, natural resource management n the mid-1980s two groups met independently, at natural resource management, have come to recognize that Ithe tropical Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico and site history is embedded in the structure and function of all at the temperate Harvard Forest in New England, to draft pro- ecosystems, that environmental history is an integral part of posals for a competition to qualify for the National Science ecological science, and that historical perspectives inform Foundation’s (NSF) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) policy development and the management of systems ranging program. -

Integrated Studies of the Drivers, Dynamics and Consequences of Landscape Change in New England

INTEGRATED STUDIES OF THE DRIVERS, DYNAMICS AND CONSEQUENCES OF LANDSCAPE CHANGE IN NEW ENGLAND HARVARD FOREST LTER-IV 2006 - 2012 David R. Foster, Principal Investigator Harvard Forest, Harvard University Co-Investigators Emery R. Boose Elizabeth A. Colburn Aaron M. Ellison Julian L. Hadley Glenn Motzkin John F. O'Keefe Harvard Forest, Harvard University David A. Orwig W. Wyatt Oswald Julie Pallant Kristina A. Stinson J. William Munger Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University Steven C. Wofsy Earth and Planetary Science, Harvard University Kathleen Donohue Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Paul R. Moorcroft Jerry M. Melillo Marine Biological Laboratory Paul A. Steudler Elizabeth S. Chilton University of Massachusetts David A. Kittredge, Jr. Eric A. Davidson Woods Hole Research Center Serita D. Frey Erik A. Hobbie University of New Hampshire Scott V. Ollinger Brian Donahue Brandeis University Knute J. Nadelhoffer University of Michigan Harvard Forest LTER IV – Project Summary The Harvard Forest (HFR) LTER is an integrated program investigating forest response to natural and human disturbance and environmental change over broad spatial and temporal scales. Involving >25 researchers, 150 undergraduate and graduate students, and a dozen institutions, HFR LTER embraces the biological, physical, and social sciences to address fundamental and applied questions for dynamic ecosystems. Our work on the ecological effects of the primary drivers of forest change in New England (Human Impacts, Natural Disturbances, -

Forest Plans of North America

Forest Plans of North America Edited by Jacek P. Siry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Pete Bettinger Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Krista Merry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Donald L. Grebner Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, USA Kevin Boston Department of Forest Engineering, Resources and Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA Christopher Cieszewski Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 32 Jamestown Road, London NW1 7BY, UK 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). -

North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area

NORTH QUABBIN CORRIDOR FOREST LEGACY AREA Application for Forest Legacy Area Expansion September 29, 2003 Massachusetts Forest Legacy Committee United States Forest Northeastern Area 11 Campus Boulevard USDA Department of Service State and Private Forestry Suite 200 Aariculture NewtownSqiare,PA 19073 File Code: 3360 Date: December 17, 2010 Jack Murray Deputy Commissioner Department of Conservation and Recreation 251 Causeway Street, Suite 600 Boston, MA 02114 Dear Mr. Murray: Enclosed is a copy of a letter from the Deputy Chief for State & Private Forestry approving the Amendment to the Massachusetts Needs Assessment for the Forest Legacy Program that expands the North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area (FLA.) I have enclosed a copy of my letter to the Deputy recommending the approval for your records. Congratulations! With the approval by the Deputy Chief, your expanded Forest Legacy Area has become eligible for sharing in Forest Legacy Program funds for acquisition of lands or interests in lands. If you have any questions regarding the Forest Legacy Program contact Deirdre Raimo. Her number is 603-868-7695. We look forward to continuing our work with you in the Forest Legacy Program. Sincerely, YN P. MALONEY Director Enclosures cc: Mike Fleming, Billy Terry, Deirdre Raimo, Neal Bungard, Scott Stewart, Terry Miller, Robert Clark Caring for the Land and Serving People Printed on Recycled Paper os” Forest Washington 1400 Independence Avenue, SW U4S Service Office Washington, DC 20250 File Code: 3360 Date: December 17, 2010 Route To: Subject: Massachusetts Forest Legacy Area Expansion Request Approved To: Kathryn P. MaloneyArea Director Thank you for your letter of December, 13, 2010, regarding the proposed expansion request to the North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area (FLA) that is part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Forest Legacy Program.