The Ecosystems Center Report 2005 the MBL Founded the Ecosystems Center As a Year-Round Research Program in 1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

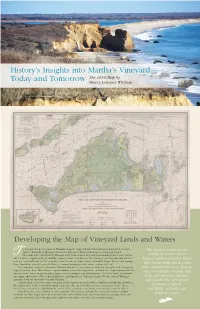

History's Insights Into Martha's Vineyard — Today and Tomorrow

History’s Insights into Martha’s Vineyard — The 1850 Map by Today and Tomorrow Henry Laurens Whiting Developing the Map of Vineyard Lands and Waters o develop this new version of Whiting’s map we extracted the Vineyard from a larger U.S. Coastal The greatest historical and Survey chart—From Muskeget Channel to Buzzard’s Bay and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. The lands were surveyed by Whiting’s crew from 1844 to 1852 and surrounding waters from 1845 to ecological treasure lies in 1857. A worn original of the beautifully engraved chart is archived in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum but for a features seldom recorded: fence year we searched fruitlessly for a pristine chart to scan. A chance visit to naturalist Nancy Weaver and mariner Dave Dandridge revealed a nearly flawless original hanging in their home on Lagoon Pond. lines (stone walls and wooden The map was scanned at Harvard’s Widener Library at a resolution of 1000 dots per inch and enlarged to rails), natural land cover (forests, display the fine detail. We inserted original elements from the larger chart: attribution to Superintendent Bache; other woodlands, swamps, and distance scale; notes on survey dates, buoys, coastal dangers, and abbreviations; No Man’s Land; a locational inset map; and views of West Chop Lighthouse and Entrance to Vineyard Sound. We also added Whiting’s fresh and saltwater marshes), signature from his surveyor’s log and a legend. and remarkably, farm details Careful study reveals the map’s stunning detail: bathymetry in feet where shallow and fathoms elsewhere; the composition of the sea-bottom (mud, sand, etc.); the speed of tidal currents; and major shoals. -

Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts By

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Harvard Forest, Harvard University Petersham, Massachusetts by David Foster, David Kittredge, Brian Donahue, Glenn Motzkin, David Orwig, Aaron Ellison, Brian Hall, Betsy Colburn and Anthony D’Amato A group of nine ecologists and historians affiliated with the Harvard Forest recently published a report on the status and future of forestlands in Massachusetts. Based on their assessment of the changing landscape, they developed a vision to protect the Commonwealth’s forests and the important economic, recreation, habitat and ecosystem services they provide. What follows is a summary of their report, “Wildlands and Woodlands: A Vision for the Forests of Massachusetts”. Massachusetts offers an unusual and urgent opportunity for forest conservation. Following widespread agricultural decline in the 19th century, the landscape reforested naturally and currently supports a wide expanse of maturing forest. Despite its large population, the state has more natural vegetation today than at nearly any time in the last three centuries. With its extensive forests supporting ecosystem processes, thriving wildlife populations, and critical environmental services for society, there is a great need to protect this landscape for the future. However, this historic window of opportunity is closing as forests face relentless development pressure. After decades of forest protection by state agencies and private organizations, patterns of land conservation and forest management are still inadequate to meet future societal and environmental needs. Large areas of protected forestland are uncommon, conserved forests are largely disconnected, important natural and cultural resources (including many plant and animal species) are vulnerable to loss, logging is often poorly planned and managed, and old-growth forests and reserves isolated from human impact are rare. -

V. Insights from Time and the Land

Insights from a Natural and Cultural Landscape V. Insights from Time and the Land Pre-History Section Ecology and conservation lessons • Template for spatial variation - gradual boundaries driven by landscape variation - soils, moisture; significant island-wide variation. • Natural processes dominate; change is slow with few notable exceptions • Vegetation structure and species missing from present. Old growth - pine, hardwoods, and mixed forest. Forest dynamics structure - old trees, CWD, damaged trees, uproots. More beech, beetlebung and hickory; very little open land or successional habitat. • People with an abundance of natural resources; highly adaptable. Accommodate growth and humans; preserve, sustain nature intact. Real distinction: passive vs active management; wildland vs woodland. All is cultural but humans can make real difference in decisions. Viable alternative is to allow natural processes to shape and reassert themselves. E.g., cord wood and timber versus old-growth; salvage or no; fire versus sheep versus succession; coastal pond - natural breach vs excavator. Topics Inertia - what happens today is very dependent on the past, may be contingent on our expectation for the future. What we do, what natural forces operate on, are conditions handed to us from history; but the entire system is in motion-erosion of features created in the past; plants and animals recovering from historical changes. Even if we do nothing much will change. Without future changes in the system - i.e. environmental change. If change occurs; inertia will condition the response - e.g. coastal erosion, shift in species. To keep things the way they are - is impossible - but even to approximate, requires huge effort. World without us, 19th C New England. -

The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation

Articles The Importance of Land-Use Legacies to Ecology and Conservation DAVID FOSTER, FREDERICK SWANSON, JOHN ABER, INGRID BURKE, NICHOLAS BROKAW, DAVID TILMAN, AND ALAN KNAPP Recognition of the importance of land-use history and its legacies in most ecological systems has been a major factor driving the recent focus on human activity as a legitimate and essential subject of environmental science. Ecologists, conservationists, and natural resource policymakers now recognize that the legacies of land-use activities continue to influence ecosystem structure and function for decades or centuries—or even longer— after those activities have ceased. Consequently, recognition of these historical legacies adds explanatory power to our understanding of modern conditions at scales from organisms to the globe and reduces missteps in anticipating or managing for future conditions. As a result, environmental history emerges as an integral part of ecological science and conservation planning. By considering diverse ecological phenomena, ranging from biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles to ecosystem resilience to anthropogenic stress, and by examining terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in tem- perate to tropical biomes, this article demonstrates the ubiquity and importance of land-use legacies to environmental science and management. Keywords: land use, disturbance, conservation, ecosystem process, natural resource management n the mid-1980s two groups met independently, at natural resource management, have come to recognize that Ithe tropical Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico and site history is embedded in the structure and function of all at the temperate Harvard Forest in New England, to draft pro- ecosystems, that environmental history is an integral part of posals for a competition to qualify for the National Science ecological science, and that historical perspectives inform Foundation’s (NSF) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) policy development and the management of systems ranging program. -

Integrated Studies of the Drivers, Dynamics and Consequences of Landscape Change in New England

INTEGRATED STUDIES OF THE DRIVERS, DYNAMICS AND CONSEQUENCES OF LANDSCAPE CHANGE IN NEW ENGLAND HARVARD FOREST LTER-IV 2006 - 2012 David R. Foster, Principal Investigator Harvard Forest, Harvard University Co-Investigators Emery R. Boose Elizabeth A. Colburn Aaron M. Ellison Julian L. Hadley Glenn Motzkin John F. O'Keefe Harvard Forest, Harvard University David A. Orwig W. Wyatt Oswald Julie Pallant Kristina A. Stinson J. William Munger Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University Steven C. Wofsy Earth and Planetary Science, Harvard University Kathleen Donohue Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Paul R. Moorcroft Jerry M. Melillo Marine Biological Laboratory Paul A. Steudler Elizabeth S. Chilton University of Massachusetts David A. Kittredge, Jr. Eric A. Davidson Woods Hole Research Center Serita D. Frey Erik A. Hobbie University of New Hampshire Scott V. Ollinger Brian Donahue Brandeis University Knute J. Nadelhoffer University of Michigan Harvard Forest LTER IV – Project Summary The Harvard Forest (HFR) LTER is an integrated program investigating forest response to natural and human disturbance and environmental change over broad spatial and temporal scales. Involving >25 researchers, 150 undergraduate and graduate students, and a dozen institutions, HFR LTER embraces the biological, physical, and social sciences to address fundamental and applied questions for dynamic ecosystems. Our work on the ecological effects of the primary drivers of forest change in New England (Human Impacts, Natural Disturbances, -

Forest Plans of North America

Forest Plans of North America Edited by Jacek P. Siry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Pete Bettinger Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Krista Merry Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Donald L. Grebner Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, USA Kevin Boston Department of Forest Engineering, Resources and Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA Christopher Cieszewski Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 32 Jamestown Road, London NW1 7BY, UK 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). -

North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area

NORTH QUABBIN CORRIDOR FOREST LEGACY AREA Application for Forest Legacy Area Expansion September 29, 2003 Massachusetts Forest Legacy Committee United States Forest Northeastern Area 11 Campus Boulevard USDA Department of Service State and Private Forestry Suite 200 Aariculture NewtownSqiare,PA 19073 File Code: 3360 Date: December 17, 2010 Jack Murray Deputy Commissioner Department of Conservation and Recreation 251 Causeway Street, Suite 600 Boston, MA 02114 Dear Mr. Murray: Enclosed is a copy of a letter from the Deputy Chief for State & Private Forestry approving the Amendment to the Massachusetts Needs Assessment for the Forest Legacy Program that expands the North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area (FLA.) I have enclosed a copy of my letter to the Deputy recommending the approval for your records. Congratulations! With the approval by the Deputy Chief, your expanded Forest Legacy Area has become eligible for sharing in Forest Legacy Program funds for acquisition of lands or interests in lands. If you have any questions regarding the Forest Legacy Program contact Deirdre Raimo. Her number is 603-868-7695. We look forward to continuing our work with you in the Forest Legacy Program. Sincerely, YN P. MALONEY Director Enclosures cc: Mike Fleming, Billy Terry, Deirdre Raimo, Neal Bungard, Scott Stewart, Terry Miller, Robert Clark Caring for the Land and Serving People Printed on Recycled Paper os” Forest Washington 1400 Independence Avenue, SW U4S Service Office Washington, DC 20250 File Code: 3360 Date: December 17, 2010 Route To: Subject: Massachusetts Forest Legacy Area Expansion Request Approved To: Kathryn P. MaloneyArea Director Thank you for your letter of December, 13, 2010, regarding the proposed expansion request to the North Quabbin Corridor Forest Legacy Area (FLA) that is part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Forest Legacy Program. -

Introduction Site-Based Science

Introduction The Harvard Forest LTER Site Review was conducted June 24 - 25, 2009 at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, MA. The site review team was composed of the following individuals: Jess Zimmerman – University of Puerto Rico; Forest ecology and social sciences integration John Porter – University of Virginia; Information management John Marshall – University of Idaho; Water relations and isotope ecology Angela Kent – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Microbial ecology Janis Boettinger – Utah State University; Soil science (Pedology) This report was prepared following one and one-half days of presentations by site scientists intermixed with visits to numerous monitoring and experimental sites in nearby forested locations. The site review team also met with REU and graduate students as well as with individual investigators during their review. The Harvard Forest LTER site (HFR) was evaluated with respect to the following five criteria: Site-based science Network participation and synthesis activities - Focused on science in a larger context, including cross-site, international, and non-LTER involvement. Information management and technology Site management - Including personnel, fiscal, institutional and logistical issues Education/outreach Each of these five criteria is evaluated with respect to quality, productivity, and impact. Site-based science Strengths Research conducted at the Harvard Forest (HFR) has repeatedly transformed the way we think about ecological systems. The HFR and its Fisher Museum focused on educating researchers and foresters alike about the history of land use in New England, showing that a landscape that was once dominated by agriculture is now a forest. The recognition that standing forests are the product of past land management, and hurricane disturbance, has changed the way we think about these forests. -

NEON Site Level Plot Summary Harvard Forest (HARV)

NEON Site Level Plot Summary Harvard Forest (HARV) Document Information Date May 2018 Author Donald C. Parizek, 12-TOL, MLRA Soil Survey Project Leader, Tolland, CT. Site Background Harvard Forest (HARV) Domain 01 is in east central Massachusetts in the towns of Petersham and Phillipston, approximately 65 miles west of Boston, MA and 50 miles northeast of Springfield, MA (Figure 1). Elevation in the Harvard Forest (HARV) Domain 01 project area ranges from a high of 1,044 feet (318 m) at Camels Hump Hill and a low of 522 feet (159 m) at the surface elevation for the Quabbin Reservoir, which is also the drinking water supply for Boston. The terrain ranges from nearly level to very steep and has been extensively modified by the late Wisconsin glacial period (10 – 12 Thousand years B.P.). HARV is found in two Major Land Resource Areas (MLRA), MLRA 144A - New England and Eastern New York Upland, Southern Part and, MLRA 144B - New England and Eastern New York Upland, Northern Part. MLRA 144A is dominated by mesic soils vegetation, diversified agriculture/land uses and extensive anthropogenic influences. MLRA 144B is dominated by frigid soils, northern hardwood and coniferous forests along with some agriculture and limited anthropogenic disturbance. The majority of the project area is found in MLRA 144A. The project area consists of approximately 12,114 Acres of non-federal land, and the dominant land cover is forest. The area is under a variety of management and ownership, with a portion owned/managed by Harvard University and the majority being owned/managed by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. -

Special Places : a Newsletter of the Trustees of Reservations

FALL 2003 VOLUME 1 1 .SpecialPLACES NO. 4 of Reservationsions I A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS OF THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS www.thetrustees.org jm^^i, smarter—Strengthening Conservation in Massachusetts Conservation sounds simple: Take care of the land and the land will take care of you. In fact, it's becoming increasingly complex. To save our landscape, we need to work smarter, better, and faster. That's the idea behind the Putnam Conservation Institute. Beneath the tranquility of it first, conservation, seems deceptively Enter the Putnam Conservation Institute (PCI), simple: care of Damde Meadows is a Take the land and the land will take a groundbreaking initiative designed to share wisdom care of you. But in today's world, conservation is and resources with conservationists of all types complex story. Restoring a often complex, costly, and time-consuming. For across the state. Named in honor of George and 1 4-acre salt marsh at example, saving some 400 acres on Mt. Tom in Nancy Putnam, PCI will provide training, networking, World's End required more Holyoke required the federal government, the and resources to increase the conservation commu- than a dozen different Commonwealth of Massachusetts, The Holyoke nity's ability to protect, care for, and interpret the Boys and Girls Club, The Trustees, $3 million, and natural and cultural resources of Massachusetts. The agencies and entities. By all six years of negotiating. Managing protected institute will be housed in the Doyle Conservation accounts, it was a learning landscapes is equally complex. Restoring a 1 4-acre Center, the state-of-the-art environmental facility process for everyone historic salt marsh in Damde Meadows at World's The Trustees is building in Leominster. -

LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN for the WATERSHEDS of the SUDBURY RESERVOIRS

LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN for the WATERSHEDS of the SUDBURY RESERVOIRS: 2005-2014 Sudbury Reservoir Gate House, October 2004 Photo by J.Kowalski Prepared by: The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Water Supply Protection, Office of Watershed Management July 2005 Acknowledgements The Land Management Plan for the Watersheds of the Sudbury Reservoirs for 2005-2014 was prepared by staff from the Natural Resources Section, Wachusett/Sudbury Section, and Quabbin/Ware River Section, as well as Divisional staff of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Division of Water Supply Protection (DWSP), Office of Watershed Management (OWM). Plan sections were drafted by many authors, including Greg Buzzell (Forester II, Wachusett Section), Brian Keevan (Forester I, Wachusett Section), Bruce Spencer (Forester III, Quabbin Section), Dan Clark (Natural Resources Specialist, Natural Resources Section), Thom Kyker-Snowman (Natural Resources Specialist, Natural Resources Section), Peter Church (Director, Natural Resources Section), Matt Hopkinson (Environmental Engineer III, Quabbin Section), Dave Small (Forest and Park Regional Supervisor I, Quabbin Section), Jim French (Regional Planner III, Natural Resources Section), and Joel Zimmerman (Regional Planner IV, OWM). Tom Mahlstedt (Archaeologist, DCR Planning and Engineering) wrote sections regarding cultural resources protection. Joel Zimmerman and Paul Penner (EDP Systems Analyst III, OWM) provided the GIS graphics and other illustrations. Photos were provided by -

SPEAKER and STAFF BIOGRAPHIES Scenarios to Simulation

SPEAKER AND STAFF BIOGRAPHIES Scenarios to Simulation SESSION 1 Varun Rao Mallampalli, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Varun Rao Mallampalli is a PhD student under Professor Mark Borsuk. His primary research interest is in the field of climate negotiations and policy modelling. He works with energy-economic agent based models and game-theoretic/ heuristic climate negotiations models to identify bottom-up and top-down processes that enable or constrain climate policy agreements. The goal of his efforts is to develop a linked agent based and negotiations model of climate policy; and to determine what specific social or economic incentives can motive a climate policy consensus. Georgia Mavrommati, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Georgia Mavrommati is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Richard Howarth’s lab in the Environmental Studies program at Dartmouth. Her primary research is defining operational conditions for achieving sustainable development in order to ensure intergenerational welfare. She employs system dynamics methodology to understand human-environment interactions and identify leverage points for policy making. She will be working with Dr. Howarth and Dr. Borsuk at the Ecosystems and Society EPSCoR project to relate scientific information about ecosystem services to preferences and decisions. Eric Booth, University of Wisconsin, Madison Eric is a lead scientist on the Yahara 2070 project, which is using stakeholder scenarios to examine potential futures for ecosystems and human well-being in Wisconsin’s Yahara Watershed. He is currently an Assistant Research Scientist in the Departments of Agronomy and Civil & Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He completed his PhD in 2011 in Limnology working within the Hydroecology Research Group in the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering.