Report B. E. Fernow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calophyllum Inophyllum L

Calophyllum inophyllum L. Guttiferae poon, beach calophyllum LOCAL NAMES Bengali (sultanachampa,punnang,kathchampa); Burmese (ph’ông,ponnyet); English (oil nut tree,beauty leaf,Borneo mahogany,dilo oil tree,alexandrian laurel); Filipino (bitaog,palo maria); Hindi (surpunka,pinnai,undi,surpan,sultanachampa,polanga); Javanese (njamplung); Malay (bentagor bunga,penaga pudek,pegana laut); Sanskrit (punnaga,nagachampa); Sinhala (domba); Swahili (mtondoo,mtomondo); Tamil (punnai,punnagam,pinnay); Thai (saraphee neen,naowakan,krathing); Trade name (poon,beach calophyllum); Vietnamese (c[aa]y m[uf]u) Calophyllum inophyllum leaves and fruit (Zhou Guangyi) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Calophyllum inophyllum is a medium-sized tree up to 25 m tall, sometimes as large as 35 m, with sticky latex either clear or opaque and white, cream or yellow; bole usually twisted or leaning, up to 150 cm in diameter, without buttresses. Outer bark often with characteristic diamond to boat- shaped fissures becoming confluent with age, smooth, often with a yellowish or ochre tint, inner bark usually thick, soft, firm, fibrous and laminated, pink to red, darkening to brownish on exposure. Crown evenly conical to narrowly hemispherical; twigs 4-angled and rounded, with plump terminal buds 4-9 mm long. Shade tree in park (Rafael T. Cadiz) Leaves elliptical, thick, smooth and polished, ovate, obovate or oblong (min. 5.5) 8-20 (max. 23) cm long, rounded to cuneate at base, rounded, retuse or subacute at apex with latex canals that are usually less prominent; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, racemose, usually unbranched but occasionally with 3-flowered branches, 5-15 (max. 30)-flowered. Flowers usually bisexual but sometimes functionally unisexual, sweetly scented, with perianth of 8 (max. -

Township Newsletter

THE NEWSLETTER OF SOUTH MIDDLETON TOWNSHIP Summer TALK of the 2021 TOWNship A few weeks ago, I released the “State of the Township” With more people comes pressures and increased demand report (found on the Township’s website) which goes into not only on public services (i.e. roads, schools, hospitals, etc.) greater detail on many of the items I will discuss here. In es- but also an obvious question – where are these people going sence, despite COVID-19 knocking us around about a bit, the to live? Since 2013, population growth in Cumberland County state of the Township is quite strong, and we are continually has exceeded available housing stock and has remained high. progressing towards a bright future of growth and prosperity. This in itself may not necessarily be cause for alarm, if vacancy In addition, many of the projects we are working on for this rates remain at a healthy point to provide selection it offers year are covered elsewhere in this Newsletter. enough choices to keep cost of living down. Unfortunately, The Board of Supervisors is committed to ensuring the vacancy rates in South Middleton for single-family homes is most effective and efficient delivery of public services while almost zero. When there is high-demand, basic economics being good stewards of your tax money. For instance, South sees prices go up, and it has in South Middleton, by about 30 Middleton’s overall tax rate is lower than 39 percent of all percent. This creates a two-pronged effect: it leads to more similar-sized communities. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

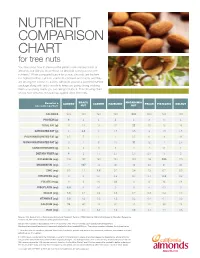

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

West Virginia's Forests

West Virginia’s Forests Growing West Virginia’s Future Prepared By Randall A. Childs Bureau of Business and Economic Research College of Business and Economics West Virginia University June 2005 This report was funded by a grant from the West Virginia Division of Forestry using funds received from the USDA Forest Service Economic Action Program. Executive Summary West Virginia, dominated by hardwood forests, is the third most heavily forested state in the nation. West Virginia’s forests are increasing in volume and maturing, with 70 percent of timberland in the largest diameter size class. The wood products industry has been an engine of growth during the last 25 years when other major goods-producing industries were declining in the state. West Virginia’s has the resources and is poised for even more growth in the future. The economic impact of the wood products industry in West Virginia exceeds $4 billion dollars annually. While this impact is large, it is not the only impact on the state from West Virginia’s forests. Other forest-based activities generate billions of dollars of additional impacts. These activities include wildlife-associated recreation (hunting, fishing, wildlife watching), forest-related recreation (hiking, biking, sightseeing, etc.), and the gathering and selling of specialty forest products (ginseng, Christmas trees, nurseries, mushrooms, nuts, berries, etc.). West Virginia’s forests also provide millions of dollars of benefits in improved air and water quality along with improved quality of life for West Virginia residents. There is no doubt that West Virginia’s forests are a critical link to West Virginia’s future. -

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Tar and Turpentine

ECONOMICHISTORY Tar and Turpentine BY BETTY JOYCE NASH Tarheels extract the South’s first industry turdy, towering, and fire-resistant longleaf pine trees covered 90 million coastal acres in colonial times, Sstretching some 150,000 square miles from Norfolk, Va., to Florida, and west along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Four hundred years later, a scant 3 percent of what was known as “the great piney woods” remains. The trees’ abundance grew the Southeast’s first major industry, one that served the world’s biggest fleet, the British Navy, with the naval stores essential to shipbuilding and maintenance. The pines yielded gum resin, rosin, pitch, tar, and turpentine. On oceangoing ships, pitch and tar Wilmington, N.C., was a hub for the naval stores industry. caulked seams, plugged leaks, and preserved ropes and This photograph depicts barrels at the Worth and Worth rosin yard and landing in 1873. rigging so they wouldn’t rot in the salty air. Nations depended on these goods. “Without them, and barrels in 1698. To stimulate naval stores production, in 1704 without access to the forests from which they came, a Britain offered the colonies an incentive, known as a bounty. nation’s military and commercial fleets were useless and its Parliament’s “Act for Encouraging the Importation of Naval ambitions fruitless,” author Lawrence Earley notes in his Stores from America” helped defray the eight-pounds- book Looking for Longleaf: The Rise and Fall of an American per-ton shipping cost at a rate of four pounds a ton on tar Forest. and pitch and three pounds on rosin and turpentine. -

Education Roadmap for Mining Professionals

Education Roadmap for Mining Professionals December 2002 Mining Industry of the Future Mining Industry of the Future Education Roadmap for Mining Professionals FOREWORD In June 1998, the Chairman of the National Mining Association and the Secretary of Energy entered into a compact to pursue a collaborative technology research partnership, the Mining Industry of the Future. Following the compact signing, the mining industry developed The Future Begins with Mining: A Vision of the Mining Industry of the Future. That document, completed in September 1998, describes a positive and productive vision of the U.S. mining industry in the year 2020. It also establishes long-term goals for the industry. One of those goals is: "Improved Communication and Education: Attract the best and the brightest by making careers in the mining industry attractive and promising. Educate the public about the successes in the mining industry of the 21st century and remind them that everything begins with mining." Using the Vision as guidance, the Mining Industry of the Future is developing roadmaps to guide it in achieving industry’s goals. This document represents the roadmap for education in the U.S. mining industry. It was developed based on the results of an Education Roadmap Workshop sponsored by the National Mining Association in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Office of Industrial Technologies. The Workshop was held February 23, 2002 in Phoenix, Arizona. Participants at the workshop included individuals from universities, the mining industry, government agencies, and research laboratories. They are listed below: Workshop Participants: Dr. -

Effect of Wood Preservative Treatment of Beehives on Honey Bees Ad Hive Products

1176 J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984. 32, 1176-1180 Effect of Wood Preservative Treatment of Beehives on Honey Bees and Hive Products Martins A. Kalnins* and Benjamin F. Detroy Effects of wood preservatives on the microenvironment in treated beehives were assessed by measuring performance of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies and levels of preservative residues in bees, honey, and beeswax. Five hives were used for each preservative treatment: copper naphthenate, copper 8-quinolinolate, pentachlorophenol (PCP), chromated copper arsenate (CCA), acid copper chromate (ACC), tributyltin oxide (TBTO), Forest Products Laboratory water repellent, and no treatment (control). Honey, beeswax, and honey bees were sampled periodically during two successive summers. Elevated levels of PCP and tin were found in bees and beeswax from hives treated with those preservatives. A detectable rise in copper content of honey was found in samples from hives treated with copper na- phthenate. CCA treatment resulted in an increased arsenic content of bees from those hives. CCA, TBTO, and PCP treatments of beehives were associated with winter losses of colonies. Each year in the United States, about 4.1 million colo- honey. Harmful effect of arsenic compounds on bees was nies of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) produce approxi- linked to orchard sprays and emissions from smelters in mately 225 million pounds of honey and 3.4 million pounds a Utah study by Knowlton et al. (1947). An average of of beeswax. This represents an annual income of about approximately 0.1 µg of arsenic trioxide/dead bee was $140 million; the agricultural economy receives an addi- reported. -

Facets of the History of New Bern

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 45 Number 3 Article 4 11-2009 Facets of the History of New Bern Michael Hill North Carolina Office of Archives and History Ansley Wegner North Carolina Office of Archives and History Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Michael and Wegner, Ansley (2009) "Facets of the History of New Bern," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 45 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol45/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Hill and Wegner: Facets of the History of New Bern Facets of the History of New Bern Michael Hill and Ansley Wegner North Carolina Office of Archives and History Survival of New Bern and Its Contribution to the Growth of a New State and Nation The affable climate and geography of the coastal plain of North Carolina made it an attractive settlement point for incoming Europeans. The land is relatively flat, and the rich soils are ideal for agriculture. The mild climate allowed for longer growing seasons, and a number of wide, slow moving rivers provided both navigation and a food source. Indeed, John Lawson, the British naturalist and explorer, described North Carolina as "a country, whose inhabitants may enjoy a life of the greatest ease and satisfaction, and pass away their hours in solid contentment." Old New Bern 57 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2009 1 Swiss American Historical Society Review, Vol. -

Class Listing

Tanbark Cavalcade Of Roses Cheryl Rangel - Secretary 1101 Peace Dr Wheeling, IL 60090 (847) 537-4743 Class Listing Class Description Place Nbr Horse Shown By Owner 001 ASB Fine Harness - Open 1 194 Oh So What Penelope Weyenberg Penelope Weyenberg 002 ASB Show Pleasure - Driving ASHA Junior Exhibitor Challenge 1 202 Majestic's Aristotle Patrick Weiler A.Weiler Amy's Acres Show Horses LLC 003 Morgan Hunter Pleasure - Open No Entries 004 Exhibition - Open Western Bridle Path 1 116 Ch Harlem's Hot Prince Mary Strohfus Mary Strohfus 2 223 Just Give Me A Reason Kim Gallenberg Kim & Dennis Gallenberg 3 252 Walterway's Kickin' Assets Sondra Loos Mike/Jennifer Elnicky 005 ASB Country Pleasure Three Gaited - 17/Under 1 288 Bella La Donna Madison Mulligan Michelle Mulligan 2 211 Dreamacres Fleetwood Mac Jordan DeRoos Jordan DeRoos 3 241 Santa Fe Son Ava Girton Richard Equine Development 4 276 Paper Heiress JJW Collin Wood Jay & Jean Wood 5 170 Warrior's Sunbird Gillian Stanley Donita Christiansen 6 237 Ciao! Bello Mio Annie Ayotte Amy Ayotte 7 228 Clever Trevor Kylie Anderson Kylie Anderson 006 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure - Walk/Trot 10/Under 1 107 Ch Pierre Cardin Nina Hendersen La Fleur Stables 2 102 Champagne On Phire Brady Kasper Greenfield Farm 007 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure 18-38 1 270 Beau & Heirrow Avis Van Zomeren Mark/Renae Van Zomeren 2 258 Nutcracker's Odyssey Lindsey Swanson Lindsey Swanson 3 251 Hotze K. Sarah Etzold Sarah Etzold 4 221 Highpoint's Currency Katie Sheets Bob Jensen Stables Inc. 5 287 Inheiritance WAF Grace Famestead Grace Famestead 008 Hackney Show Pleasure Pony - Driving 1 264 Buckle Up HS Veronica Lindstrom Doug/Veronica Lindstrom 2 261 Finnagan Winnagan Audra Brizgys Christine Johnson 009 Morgan Classic Pleasure - Driving 1 139 Sarde's Soul Sister Kim Loewer Kim Loewer 010 Exhibition - Open English Pleasure - Walk/Trot 11/Over 1 266 PO's Nicolite Brooke Whitney R.Sperl/S. -

Renewables for Mining in Africa

Renewables for Mining in Africa © 2020 Bird & Bird All Rights Reserved | 1 A few figures Report resulting from the conference held on 29 January 2020 at Bird & Bird in Paris Introduction by Boris Martor, Partner Africa currently accounts for 15% of global mining expenditure, which remains low in relation to the continent’s resources. Mining is therefore set to expand in the coming years. Africa’s power generation capacity is 80 GW, of which 40GW is in South Africa and 23 GW is allocated to mining projects, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, about 50% of the electricity production in Sub-Saharan Africa is generated by the mining sector. In addition, the cost of electricity generation in a mining project is between 10 and 35% of the project cost. Thus, the weight of the mining industry in the African energy landscape is very important and the needs are growing as mining exploitation increases. Moreover, in the mining sector, there is a permanent risk of energy blackouts. Indeed, mining industries have an increased dependency on energy. A temporary or more longer term loss of power would have strong financial implications. Renewable energy infrastructures, such as mini-grids, are now being considered as an answer to all this. What is a mini-grid? An integrated energy systems consisting of a group interconnected Distribution Energy Ressources (like Production sources, PV, Genset, along with energy Storage to control some Controllable Loads) with clearly defined electrical Boundaries. • To increase resiliency • To manage Site energy Consumption