Scheherazade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with MO Just Say

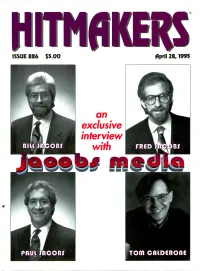

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

The Bible Vision

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University TUFW Alumni Publications Publications for TUFW and Predecessors 10-1-1936 The iB ble Vision Fort Wayne Bible Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tufw-alumni-publications Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Fort Wayne Bible Institute, "The iB ble Vision" (1936). TUFW Alumni Publications. 225. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tufw-alumni-publications/225 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications for TUFW and Predecessors at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in TUFW Alumni Publications by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'WHERE THERE IS NO VISION, THE PEOPLE PERISH' THE BIBLE VISION '*Write the znsion and make it plain" THE HEAVENLY VISION Rev. J. E. Ramseyer THE THEOLOGY OF THE HYMNBOOK Dr. John Greenfield THE CROSS ANTICIPATED Mr. John Tuckey THE EPISTLE TO THE GALATIANS Rev. B. F. Leightner WHAT'S NEW AT THE BIBLE INSTITUTE WITH THE ALUMNI OCTOBER, 1936 Publication of the Fort Wayne Bible Institute Fort Wayne, Indiana 1 The Bible Vision Published monthly by THE FORT WAYNE BIBLE INSTITUTE S. A. WITMER, Editor B. F. LEIGHTNER, Associate Editor LOYAL RINGENBERG, Associate Editor HARVEY MITCHELL, Editor of Fellowship Circle Department Publisher Economy Printing Concehn, Berne, Indiana Yearly Subscription, Seventy- Five Cents; Sixteen Months for One Dollar; Three Years for Two Dollars; Single Copy for Ten Cents. Address all correspondence regarding subscriptions or subject-matter to the Fort Wayne Bible Institute, Fort Wayne, Indiana. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Images of the Pregnant Body and the Unborn Child in England, 1540–C.1680 Rebecca Whiteley*

Social History of Medicine Vol. 32, No. 2 pp. 241–266 Roy Porter Student Prize Essay Figuring Pictures and Picturing Figures: Images of the Pregnant Body and the Unborn Child in England, 1540–c.1680 Rebecca Whiteley* Summary. Birth figures, or print images of the fetus in the uterus, were immensely popular in mid- wifery and surgical books in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But despite their central role in the visual culture of pregnancy and childbirth during this period, very little critical attention has been paid to them. This article seeks to address this dearth by examining birth figures in their cultural context and exploring the various ways in which they may have been used and interpreted by early modern viewers. I argue that, through this process of exploring and contextual- ising early modern birth figures, we can gain a richer and more nuanced understanding of the early modern body, how it was visualised, understood and treated. Keywords: midwifery; childbirth; pregnancy; visual culture; print culture An earnest, cherubic toddler floats in what looks like an inverted glass flask. Accompanied by numerous fellows, each figure demonstrates a different acrobatic pos- ture (Figure 1). These images seem strange to a modern eye: while we might suppose they represent a fetus in utero (which indeed they do), we are troubled by their non- naturalistic style, and perhaps by a feeling that they are rich in a symbolism with which we are not familiar. Their first viewers, in England in the 1540s, might also have found them strange, but in a different way, as these images offered to them an entirely new picture of a bodily interior that was largely understood to be both visually inaccessible and inherently mysterious. -

ENGLISH SONGS 5:15 Who CDG 152 - 8 1973 James Blunt CDG 241 - 12 1985 Bowling for Soup DVD 206 - 17 1999 Prince WKL 25 B 5 1, 2 STEP Ciara Feat

www.swengi.fi Updated 03/13 ENGLISH SONGS 5:15 Who CDG 152 - 8 1973 James Blunt CDG 241 - 12 1985 Bowling For Soup DVD 206 - 17 1999 Prince WKL 25 B 5 1, 2 STEP Ciara feat. Missy Elliott DVD 205 - 2 1,2,3,4 Plain White T's CDG 259 - 6 100 YEARS 5 For Fighting DVD 204 - 10 100% PURE LOVE Crystal Waters UK 10 A 1 10TH AVE FREEZE OUT Bruce Springsteen CDG 105 - 15 18 AND LIFE Skid Row CDG 173 - 12 19TH NERVOUS BREAKDOWN Rolling Stones CDG 257 - 3 2 BECOME 1 Spice Girls DVD 30 - 11 2 HEARTS Kylie Minoque CDG 243 - 1 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY Elvis DVD 4 - 1 24 HOURS AT A TIME Marshall Tucker CDG 116 - 11 25 MINUTES Michael Learns To Rock WAD 12 B 1 4 IN THE MORNING Gwen Stefani CDG 240 - 14 4 MINUTES Madonna CDG 238 - 15 500 MILES Bobby Bare DVD 188 - 8 500 MILES Peter, Paul & Mary WKL 8 A 5 7 THINGS Miley Cyrus DVD 95-2-59 837-5309 JENNY Tommy Tutone DVD 95-3-32 9 CRIMES Damien Rice CDG 236 - 18 9 TO 5 Dolly Parton CDG 271 - 9 96 TEARS Question Mark&Mysterians CDG 155 - 5 A TEAM, THE Ed Sheeran CDG 283 - 10 ABC Michael Jackson DVD 95-2-39 ABOUT YOU NOW Sugababes CDG 243 - 2 ABRAHAM MARTIN AND JOHN Dion CDG 274 - 5 ACES HIGH Iron Maiden CDG 176 - 13 ACHY BREAKY HEART Billy Rae Cyrus SF 3 A 14 ACHY BREAKY SONG Weird Al Yankovic CDG 123 - 14 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE Fiona Apple CDG 108 - 3 ADDICTED TO LOVE Robert Palmer WKL 2 B 1 ADDICTED TO LOVE Tina Turner CDG 178 - 11 ADDICTED TO SPUDS Weird Al Yankovic CDG 123 - 8 ADIA Sarah McLachlan CDG 108 - 4 ADVERTISING SPACE Robbie Wiliams CDG 227 - 14 AFRICA Toto WKL 28 B 14 AFTER ALL Al Jarreau CDG 151 - -

“Living the Dream”

George A. Mason Wilshire Baptist Church th A Season for Dreamers 4 Sunday of Advent 22 December 2019 Last“Living in series, the Dream” Dallas, Texas Luke 1:26-38, 46-55 It was the only thing that always This song is to the country of worked to quiet her. It is the Austria about what Kate Smith’s only thing that works to quiet version of “God Bless America” is him. to us—not a national anthem but a patriotic ballad. Edelweiss is a One of the pleasures of white flower that grows bravely grandparenting is seeing how in the highest altitudes. the children you parented Unfortunately, it’s also too often parent. Kim and I were in New a symbol of racist white power. York a few weeks ago, staying with our daughter, Jillian. It was Lullabies are powerful ways of her son River’s bedtime, and he calming children and putting wasn’t having it. Then I heard it. them to sleep. What I want to A song. A lullaby. Something I suggest to you today is that they hadn’t heard since she was a are also powerful ways of riling little girl that became an people and waking them up to earworm in my head night after act. Lullabies can set you to night—“Edelweiss.” dreaming and also to living the dream. lullaby Jillian grew up with stories. It’s no surprise she majored in The very word is curious. acting inThe college Sound and of isMusic our Some say—and for all the family drama queen, don’t you research I have done this week, I know?! was a still can’t confirmLilith, it—that be gone. -

Jacob Druckman

JACOB DRUCKMAN: LAMIA THAT QUICKENING PULSE | DELIZIE CONTENTE CHE L’ALME BEATE | NOR SPELL NOR CHARM | SUITE FROM MÉDÉE [1] THAT QUICKENING PUlsE (1988) 7:41 JACOB DRUCKMAN 1928–1996 Francesco Cavalli/Jacob Druckman: [2] DELIZIE CONTENTE CHE L’ALME BEATE (arr. 1985) 2:48 THAT QUICKENING PULSE [3] NOR SPELL NOR CHARM (1990) 11:37 DELIZIE CONTENTE CHE L’ALME BEATE Marc-Antoine Charpentier/Jacob Druckman: NOR SPELL NOR CHARM SUITE FROM MÉDÉE (arr. 1985) [4] I. Ouverture 2:14 SUITE FROM MÉDÉE [5] II. Prélude 2:45 [6] III. Rondeau pour les Corinthiens 1:50 LAMIA [7] IV. Loure 4:46 [8] V. Passepied & Choeur 3:24 LAMIA (1986) LUCY SHELTON soprano [9] I. Folk conjuration to make one courageous 2:09 [10] II. Metamorphoses, Book VII; BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT Folk conjuration to dream of one’s future husband 7:01 [11] III. Folk conjuration against death or other absence GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR of the soul 4:59 [12] IV. Stanza degli Incanti de Medea; Tristan und Isolde; Periapt against theeves 5:08 TOTAL 56:24 COMMENT By Jacob Druckman Lamia was the name of a sorceress of Greek mythology and has come to mean “sorcer- ess” in the generic sense. The concept of the work grew out of a particular performance of my Animus II by my dear friend and colleague, the great American mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani at the Aspen Colorado Music Festival in 1972. Ms. DeGaetani, who has magnificently performed and recorded several of my works, gave a particularly magical performance that night in which everything that sounded and befell seemed to be the direct result of her will and her powers. -

The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus the Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus an Egyptian Philosopher

The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus an Egyptian Philosopher In 17 Books translated formerly out of the Arabic into Greek, and thence into Latin, and Dutch, and now out of the Original into English by that Learned Divine Doctor Everard. Printed by Robert White in London in 1650 Judicious Reader, This Book may justly challenge the first place for antiquity, from all of the Books in the World, being written some hundred of years before Moses time, as I shall endeavour to make good. The Original (as far as it is know to us) is Arabic, and several Translations thereof have been published, as Greek, Latin, French, Dutch, etc., but never English before. It is a pity that the Learned Translator [Doctor Everard] is not alive, and received himself, the honour, and thanks due to him from Englishmen; for his good will to, and pains for them, in translating a Book of such infinite worth, out of the Original, into their Mother- tongue. Concerning the Author of the Book itself, Four things are considered, viz His Name, Learning, Country and Time. 1) The name by which he was commonly titled is, Hermes Trismegistus, i.e., Mercurious Ter Maximus, or, The thrice greatest Intelligencer. And well might he be called Hermes, for he was the first Intelligencer in the World (as we read of) that communicated Knowledge to the sons of Men, by Writing, or Engraving. He was called Ter Maximus, for some Reasons, which I shall afterwards mention. 2) His Learning will appear, as by his Works; so by the right understanding the Reason of his Name. -

DECLARATION of Jane Sunderland in Support of Request For

Columbia Pictures Industries Inc v. Bunnell Doc. 373 Att. 1 Exhibit 1 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation Motion Pictures 28 DAYS LATER 28 WEEKS LATER ALIEN 3 Alien vs. Predator ANASTASIA Anna And The King (1999) AQUAMARINE Banger Sisters, The Battle For The Planet Of The Apes Beach, The Beauty and the Geek BECAUSE OF WINN-DIXIE BEDAZZLED BEE SEASON BEHIND ENEMY LINES Bend It Like Beckham Beneath The Planet Of The Apes BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE 2 BLACK KNIGHT Black Knight, The Brokedown Palace BROKEN ARROW Broken Arrow (1996) BROKEN LIZARD'S CLUB DREAD BROWN SUGAR BULWORTH CAST AWAY CATCH THAT KID CHAIN REACTION CHASING PAPI CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN 2 Clearing, The CLEOPATRA COMEBACKS, THE Commando Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes COURAGE UNDER FIRE DAREDEVIL DATE MOVIE 4 Dockets.Justia.com DAY AFTER TOMORROW, THE DECK THE HALLS Deep End, The DEVIL WEARS PRADA, THE DIE HARD DIE HARD 2 DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE DODGEBALL: A TRUE UNDERDOG STORY DOWN PERISCOPE DOWN WITH LOVE DRIVE ME CRAZY DRUMLINE DUDE, WHERE'S MY CAR? Edge, The EDWARD SCISSORHANDS ELEKTRA Entrapment EPIC MOVIE ERAGON Escape From The Planet Of The Apes Everyone's Hero Family Stone, The FANTASTIC FOUR FAST FOOD NATION FAT ALBERT FEVER PITCH Fight Club, The FIREHOUSE DOG First $20 Million, The FIRST DAUGHTER FLICKA Flight 93 Flight of the Phoenix, The Fly, The FROM HELL Full Monty, The Garage Days GARDEN STATE GARFIELD GARFIELD A TAIL OF TWO KITTIES GRANDMA'S BOY Great Expectations (1998) HERE ON EARTH HIDE AND SEEK HIGH CRIMES 5 HILLS HAVE -

Easter Seal #11

Easter Seal #11 ‘The Quickening Power of God’ Bro. Lee Vayle - June 5, 1991 Shall we pray. Heavenly Father, we’re grateful to be able to come again to Your house, which You’ve so wonderfully provided for us, beyond all expectations and desires. It’s marvelous how You continue to do Your good work amongst us Lord, giving us the Word which is meat in due season, help for this very day in which we live. Now we pray, Lord, You’ll feed our souls tonight by the bread of life, may we understand that which has been given to us by vindication, and we’ll praise Your Name forever. In Jesus’ Name, we pray. Amen. You may be seated. 1. Now we’re into number 11 of Easter Seal which we did not take last Sunday, took a little message that I wanted to bring you, and now we go back of course to this message that Bro. Branham preached in Phoenix, back in ’65. Now having already dealt with the Easter Seal by way of several hours of comments, it should be no problem to recall that according to Bro. Branham what took place at the resurrection of Jesus, and at Pentecost, has been proven to be historically accurate, because the same Spirit that raised Jesus from the dead is here today, manifesting Itself in the Son of man ministry, which according to Luke 17 precedes the Rapture. Now of course that’s a definitive statement concerning Bro. Branham’s ministry. As the prophet of this hour, Elijah, to the Gentiles, he fulfilled, that is God fulfilled in his ministry, because it would be God, as God is in the prophets and doing all the works.