War Is Deceit, an Analysis of a Contentious Hadith on the Morality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Struggle Against Musaylima and the Conquest of Yamama

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST MUSAYLIMA AND THE CONQUEST OF YAMAMA M. J. Kister The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The study of the life of Musaylima, the "false prophet," his relations with the Prophet Muhammad and his efforts to gain Muhammad's ap- proval for his prophetic mission are dealt with extensively in the Islamic sources. We find numerous reports about Musaylima in the Qur'anic commentaries, in the literature of hadith, in the books of adab and in the historiography of Islam. In these sources we find not only material about Musaylima's life and activities; we are also able to gain insight into the the Prophet's attitude toward Musaylima and into his tactics in the struggle against him. Furthermore, we can glean from this mate- rial information about Muhammad's efforts to spread Islam in territories adjacent to Medina and to establish Muslim communities in the eastern regions of the Arabian peninsula. It was the Prophet's policy to allow people from the various regions of the peninsula to enter Medina. Thus, the people of Yamama who were exposed to the speeches of Musaylima, could also become acquainted with the teachings of Muhammad and were given the opportunity to study the Qur'an. The missionary efforts of the Prophet and of his com- panions were often crowned with success: many inhabitants of Yamama embraced Islam, returned to their homeland and engaged in spreading Is- lam. Furthermore, the Prophet thoughtfully sent emissaries to the small Muslim communities in Yamama in order to teach the new believers the principles of Islam, to strengthen their ties with Medina and to collect the zakat. -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Unveiling the Great Deception in Al-Zawahiri's 'Exoneration of the Nation'

1 Unveiling the Great Deception in al-Zawahiri’s ‘Exoneration of the Nation’ Al-Sayyid Imam Abdul-Aziz al-Sharif Dr Fadl November 2008 2 Part I “Al-Zawahiri’s book is full of lies, calumnies, jurisprudential fallacies, and indirections” Dr Fadl, the mastermind of the jihadists Recently, The Middle Eastern newspaper ‘Al-Sharq Al-Awsat’ has published several sequels of Dr Fadl’s “Unveiling al-Zawahiri’s Deceptions in His ‘Exoneration of the Nation’ ” (Mudhakkirat al-Ta’riya li Kitaab al-Tabri’a), which the author wrote as a response to the book written not long ago by the second man in command in al-Qaeda, under the title ‘Exoneration of the Nation of the Pen and the Sword of the Denigrating Charge of being Undetermined and Powerless’. In this response, Dr Fadl not only debunks the ideas of al-Zawahiri, but he also divulges many aspects of his life and personality that are usually unknown to the general public Tuesday the 20/Dhu al-Qi‘da/ 1429 AH – 18/ November/ 2008, Cairo Issue No 10948 Al-Sharq Al-Awsat By Muhammad Mustafa Abu Shama A year ago [in 2007], al-Sayyid Imam Abdul-Aziz al-Sharif, Dr Fadl, the former mastermind and ideologue of the Jihad Organization (Tanzeem) of Egypt, launched his jurisprudential reviews on jihadi activity, in a booklet titled “The Document for the Guidance of Jihadi Action in Egypt and the World’. These reviews, which came in the form of disavowals of the prevailing jihadi philosophy in the Muslim world, have had a significant impact among the jihadists and were since then considered a turning point in the history of the Islamist movements. -

D2light the Bookfinal.Qxd

From Darkness into Light An Account of the Messenger’s struggle to make Islam dominant Salim Fredericks & Ahmer Feroze Al KhilafahPublications Al-Khilafah Publications Suite 298 56 Gloucester Road London SW7 4UB e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.khilafah.com This book is dedicated to all those who carry the call of Islam in its entirety. Those who seek to establish Allah's Deen firmly according to the Sunnah of His Messenger, Muhammad . Their numbers, past and Rajab 1421 AH / 2000 CE present are many. Inshallah their efforts and sacrifice will not go un- noticed by Allah , The All Knowing, The All Seeing. ISBN 1 899 57421 2 May Allah reward you and strengthen your lines. Indeed, the life of this world is short, and we pray that in return for Translation of the Qur’an what you have given up Allah will (Inshallah) reward you a magnificent reward. And Allah has power over all things, but most of mankind It should be perfectly clear that the Qur’an is only authentic in its original know not. language, Arabic. Since perfect translation of the Qur’an is impossible, we have used the translation of the meaning of the Qur’an’ throughout the book, as the result is only a crude meaning of the Arabic text. Qur’anic Ayat and transliterated words have been italicised in main part of the book. Saying of the Messenger appear in bold - subhanahu wa ta’ala - sallallahu ‘alaihi wa sallam RA - radhi allaho anha/anho AH - After Hijrah CE - Common Era 8 The Invitation to Islam 67 " If you accept Islam, you will remain in command of your country; but if you refuse my Call, you've got to remember that all your possessions are perishable. -

Journal of Religion & Society

Journal of Religion & Society Volume 9 (2007) The Kripke Center ISSN 1522-5658 Muhammad’s Jewish Wives Rayhana bint Zayd and Safiya bint Huyayy in the Classic Islamic Tradition Ronen Yitzhak, Western Galilee College, Israel Abstract During his life, the Prophet Muhammad (570-632) married 12 different wives among whom were two Jewish women: Rayhana bint Zayd and Safiya bint Huyayy. These two women were widows whose husbands had been killed in wars with Muslims in Arabia. While Rayhana refused to convert to Islam at first and did so only after massive pressure, Safiya converted to Islam immediately after being asked. Rayhana died a few years before Muhammad, but Safiya lived on after his death. Classic Islamic sources claim that the Muslims did not like Rayhana because of her beauty and so made an issue of her Jewish origin, with Muhammad being the only one to treat her well. After Muhammad’s death, Safiya lived among his other wives in Mecca, but did not take part in the political intrigues at the beginning of Islam, in contrast to the other wives, especially the most dominant and favorite wife, Aisha. Introduction [1] According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet Muhammad married 12 different wives and had even more concubines. The custom of taking concubines was widespread in ancient times and therefore also was practiced in Arabia. Concubines were often taken in the context of war booty, and it seems that this is the reason for including in the Qur’an: “(you are forbidden) the married women, but not the concubines you, own” (Q 4:24; al-Qurtubi: 5.106). -

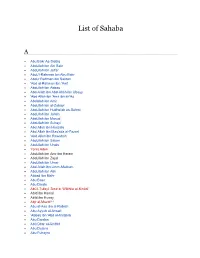

List of Sahaba

List of Sahaba A Abu Bakr As-Siddiq Abdullah ibn Abi Bakr Abdullah ibn Ja'far Abdu'l-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr Abdur Rahman ibn Sakran 'Abd al-Rahman ibn 'Awf Abdullah ibn Abbas Abd-Allah ibn Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As Abdallah ibn Amir Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi Abdullah ibn Jahsh Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Suhayl Abd Allah ibn Hanzala Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah Abdullah ibn Salam Abdullah ibn Unais Yonis Aden Abdullah ibn Amr ibn Haram Abdullah ibn Zayd Abdullah ibn Umar Abd-Allah ibn Umm-Maktum Abdullah ibn Atik Abbad ibn Bishr Abu Basir Abu Darda Abū l-Ṭufayl ʿĀmir b. Wāthila al-Kinānī Abîd ibn Hamal Abîd ibn Hunay Abjr al-Muzni [ar] Abu al-Aas ibn al-Rabiah Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib Abu Dardaa Abû Dhar al-Ghifârî Abu Dujana Abu Fuhayra Abu Hudhaifah ibn Mughirah Abu-Hudhayfah ibn Utbah Abu Hurairah Abu Jandal ibn Suhail Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir Abu Musa al-Ashari Abu Sa`id al-Khudri Abu Salama `Abd Allah ibn `Abd al-Asad Abu Sufyan ibn al-Harith Abu Sufyan ibn Harb Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Abu Zama' al-Balaui Abzâ al-Khuzâ`î [ar] Adhayna ibn al-Hârith [ar] Adî ibn Hâtim at-Tâî Aflah ibn Abî Qays [ar] Ahmad ibn Hafs [ar] Ahmar Abu `Usayb [ar] Ahmar ibn Jazi [ar][1] Ahmar ibn Mazan ibn Aws [ar] Ahmar ibn Mu`awiya ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Qatan al-Hamdani [ar] Ahmar ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Suwa'i ibn `Adi [ar] Ahmar Mawla Umm Salama [ar] Ahnaf ibn Qais Ahyah ibn -

Fra Mørke Til Lys

fra Mørke til Lys En Opgørelse over Sendebudets (saaws) Kamp for at gøre Islam Dominerende fra Mørke til Lys En Opgørelse over Sendebudets (saaws) Kamp for at gøre Islam Dominerende Salim Fredericks & Ahmed Feroze Oversat fra Engelsk Al-Khilafah Publikationer Denne bog dedikeres til alle dem, som bærer Islams kald i sin helhed. Dem, som søger at etablere og rodfæste Allahs Deen ifølge Hans Sendebud Muhammads (saaws) Sunnah. Deres antal, fortidens og nutidens, er mange. Deres indsats og ofringer vil insha Allah, ikke være spildt hos Allah (swt), den Alvidende, Alseende. Må Allah (swt) belønne jer og styrke jeres rækker. Dette liv er sandelig kort, og vi håber at Allah (swt), til gengæld for hvad I har opgivet, vil belønne jer med en overvældende belønning. Og Allah (swt) har magt over alting, men de fleste mennesker ved det ikke. Indhold Indledning 05 Åbenbaringens Effekt på Samfundet i Makkah 08 Muhammads (saaws) Politiske Parti 14 Islams Fjender 18 Den Målbevidste Søgen efter Nusrah - for at Opnå Statslederskabet 24 Hijrahs Politiske Betydning 28 Etablering af Islam som levemåde 31 Kaldet til Islam 38 Begivenheder i Bani Sa’idas Gårdsplads 46 Konklusion 49 Det Varme Kald fra Hizb-ut-Tahrir 53 Bibliografi 55 Indledning Siraajan Muneera (En Lysende Lampe) Vi lever i en æra af dyb mørke. Verdens resurser forbruges stort set af dem, som besidder mindst og producerer mindst. Verdens politiske system er således, at det ser ud til, at intet kan bryde denne status quo med Vestens hegemoni. Denne cyklus med krige og traktater, traktater og krige, har gennem det 20. -

Umm Kulthum Bint ‘Ali Zaynab Bint ‘Ali the Shape That We See in the Present Prophet

TIMELINE OF THE LIFE OF PROPHET MUHAMMAD AND THE KHULAFĀ AR-RASHIDŪN “...SO ADHERE TO MY SUNNAH AND THE SUNNAH OF THE RIGHTLY-GUIDED KHULAFA...”(ABU DAWUD) SUMMARIZED LINEAGE OF THE PROPHET AND HIS RELATIONSHIP WITH THE KHULAFA AR-RASHIDUN 53-37 BH 28-13 BH 13-8 BH 8-4 BH 4-2 BH 1 BH-1 AH 1-2 AH 2-4 AH 4-6 AH 6-7 AH 7-8 AH 8-9 AH 9-11 AH 11 AH 11-13 AH 13-14 AH 15-17 AH 18-23 AH 23-31 AH 33-36 AH 36-37 AH 38-50 AH 570 CE 594 CE 608 CE 613 CE 617 CE 620 CE 622 CE 623 CE 625 CE 626 CE 628 CE 629 CE 630 CE 632 CE 632 CE 634 CE 636 CE 639 CE 643 CE 653 CE 656 CE 660 CE Indicates multiple generations in between Adam 12 Rabi’ al-Awal, 11 AH 11 AH 28 BH Sha’ban 4 AH Sha’ban, 6 AH Muharram, 7 AH Jumada al-Awal, 8 AH Rajab, 9 AH Jumada al-Thani, 13 AH Sha’ban 15 AH 18 AH Dhul Hijjah, 23 AH 33 AH Rabi’ al-Thani, 36 AH 9 Safar, 38 AH Indicates direct descendant 13 BH – 10 BH Dhul Hijjah, 8 BH Shawwal, 4 BH 1 BH Rabi’ al-Awal, 1 AH 17th Ramadan, 2 AH Nuh DEATH OF PROPHET DEATH OF FATIMAH MARRIAGE TO SECRET PREACHING ‘UMAR IBN AL- PROPHET’S JOURNEY MUS’AB IBN UMAIR BUILDING OF MASJID BATTLE OF BADR BIRTH OF AL-HUSAYN SLANDER OF Ā’ISHA EXPEDITION TO BATTLE OF MU’TAH EXPEDITION TO TABUK As foretold by the Prophet , BATTLE OF YARMOUK BATTLE OF QADISIYYAH GREAT FAMINE DEATH AND BURIAL OF RISE OF ABDULLAH IBN ‘ALI LEAVES BATTLE OF NAHRAWAN The Prophet secretly preaches his A group of 313 Muslims face off While the army and its caravan was The envoy the Prophet sends The Expedition to Tabuk takes MUHAMMAD Another major battle between the Under the command of Sa’ad ibn A severe drought causes famine The Khawarij are dealt a huge blow Indicate relations by marriage/concubinage KHADIJAH KHATTAB ACCEPTS TO AT-TA’IF SENT TO YATHRIB AN-NABAWI IBN ‘ALI KHAYBAR Fatimah is the first of his family to ‘UMAR SABA MADINAH FOR KUFA returning from the expedition of to the ruler of Busra in al-Sham is place, in which the Prophet The Prophet dies while lying on the Byzantine forces and the Muslims Abi Waqqas , the Muslims win the in Arabia. -

Jews in the Qurʾān: an Evaluation of the Naming and the Content

JEWS IN THE QURʾĀN: AN EVALUATION OF THE NAMING AND THE CONTENT Salime Leyla Gürkan İstanbul 29 Mayıs University, Istanbul-Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Abstract No other people are mentioned in the Qurʾān as often as the people of Israel. They appear in sixteen sūrahs and approximately forty verses by name (banū Isrāʾīl). The Qurʾān also makes reference to the Jews either by name (al-yahūd/hūd) or within the context of the people of the book (ahl al-kitāb). This paper aims to discuss the Qurʾānic verses about the Jews and the people of Israel in terms of the naming and the content. Key questions to be addressed are: What is the purpose of the frequent mention of the people of Israel in the Qurʾān? What is the context and the content of the verses about the Jews and the people of Israel both in Meccan and Medinan sūrahs? What message or messages are intended to or can be conveyed by these verses? Key Words: Qurʾān, Jews (yahūd/hūd), the people of Israel (banū Isrāʾīl), the people of the book (ahl al-kitāb), the Prophet Muḥammad, Muslims, Islām. Ilahiyat Studies Copyright © Bursa İlahiyat Foundation Volume 7 Number 2 Summer / Fall 2016 p-ISSN: 1309-1786 / e-ISSN: 1309-1719 DOI: 10.12730/13091719.2016.72.148 164 Salime Leyla Gürkan Introduction The word “religion (dīn)” is used in the Qurʾān as a term that includes all religion(s).1 Nevertheless, the Qurʾān does not mention religions or religious systems individually or by name (in fact, there is no Qurʾānic usage of a plural form of the word dīn, i.e., adyān). -

An International and Islamic Perspective of Hamas

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 83 Issue 2 Symposium: Rethinking Payments in Article 21 Law April 2008 An International and Islamic Perspective of Hamas Amy Chiang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Amy Chiang, An International and Islamic Perspective of Hamas, 83 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1021 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol83/iss2/21 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. AN INTERNATIONAL AND ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVE OF HAMAS AMY CHIANG* God is its goal; The Messenger is its Leader. The Qur'an is its Constitution. Jihad is its methodology, and Death for the sake of God is its most coveted desire. -Hamas 1 INTRODUCTION In recent times, no group has sparked as much controversy as Hamas. While it won democratic elections in January 2006, the United States, the European Union, and Israel categorize Hamas as a terrorist organization. 2 How could a "terrorist organization" emerge as a political victor? To un- derstand this group better it is important to evaluate it under international humanitarian law and Islamic law. Analyzing Hamas using only international law fails to take into ac- count that Hamas is an organization that claims to derive its principles from Islamic law. -

The Bride's Boon

You would follow the traditions of your predecessors inch by inch and arm by arm even if they entered a hole of a lizard 82 82 Imitation of foreigners deconstructs one’s personality. It is a sign of one’s weakness. It is the weak who imitates the strong. Imitating the unbelievers in their clothes may lead to imitating them in their ideology and belief. The dress should not be similar to what is known as the custom of unbelievers. This requirement is derived from the general rule of Shari' ah that Muslims should have their distinct personality and should differentiate their practices and appearance from that of the unbelievers. Therefore, a Muslim woman should have the following requirements in her dress: (1)Extent of covering: the dress must cover the whole body except for the areas specifically exempted: face and hands. (2)Overall appearance: the dress should not be such that it attracts men's attention to the woman's beauty. The Qur'an clearly prescribes the requirements of the woman's dress for the purpose of concealing adornment. How such adornment could be concealed if the dress is designed in a way that it attracts men's eyes to the woman. (3) Thickness: the dress should be thick enough so as not to show the color of the skin it covers, or the shape of the body which it is supposed to hide. The Prophet (pbuh) said, "In latter (generations) of my Ummah there will be dressed but naked. (4) Looseness: the dress must be loose enough so as not describe the shape of a woman's body. -

Miftaah Online Notes: Hadith | Session 2

MIFTAAH ONLINE PROPHETIC TRADITIONS Imam Ali Hofioni S Hadith– Sanctity of Human Life E S Some try to use this hadith to attack Islam, and for some, S doubts can come into their heart. It is important to ask I someone qualified to answer these questions that come O to mind and to not let them fester. N َ َﺣ ﱠﺪﺛَ َﻨﺎ َﻋ ْﺒ ُﺪ ﷲﱠِ ﺑْ ُﻦ ُﻣﺤَ ﱠﻤ ٍﺪ ا ْﻟ ُﻤ ْﺴ َﻨ ِﺪي، َﻗﺎ َل َﺣ ﱠﺪﺛَ َﻨﺎ أﺑُﻮ َر ْوح ا ْﻟﺤَﺮَ ِﻣﻲ ﺑْ ُﻦ ُﻋ َﻤﺎ َر َة، ﱡ ٍ ﱡ َ َ ُ ُ َ َ ﻗﺎ َل َﺣ ﱠﺪﺛ َﻨﺎ ﺷ ْﻌ َﺒﺔ، َﻋ ْﻦ َوا ِﻗ ِﺪ ﺑْ ِﻦ ُﻣﺤَ ﱠﻤ ٍﺪ، ﻗﺎ َل َﺳ ِﻤ ْﻌ ُﺖ أﺑِﻲ ﻳُﺤَ ﱢﺪ ُث، َﻋ ِﻦ اﺑْ ِﻦ 2 َ " ُ َ ُ ُﻋ َﻤﺮَ، أ ﱠن َر ُﺳﻮ َل ﷲﱠِ ﺻﲆ ﷲ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ وﺳﻠﻢ َﻗﺎ َل أ ِﻣ ْﺮ ُت أ ْن أ َﻗﺎﺗِ َﻞ اﻟ ﱠﻨﺎ َس َ َ َ َﺣ ﱠﺘﻰ ﻳَ ْﺸ َﻬ ُﺪوا أ ْن ﻻَ ِإﻟ َﻪ ِإﻻﱠ ﷲﱠُ َوأ ﱠن ُﻣﺤَ ﱠﻤ ًﺪا َر ُﺳﻮ ُل ﷲﱠِ، َوﻳُ ِﻘﻴ ُﻤﻮا اﻟ ﱠﺼﻼَ َة، َ َ ُ َ َ َوﻳُ ْﺆﺗُﻮا اﻟﺰﱠ َﻛﺎ َة، ﻓ ِﺈ َذا ﻓ َﻌﻠﻮا َذﻟِ َﻚ َﻋ َﺼ ُﻤﻮا ِﻣﻨﱢﻲ ِد َﻣﺎ َء ُﻫ ْﻢ َوأ ْﻣ َﻮاﻟ ُﻬ ْﻢ ِإﻻﱠ ﺑِﺤَ ﱢﻖ . " ا ِﻹ ْﺳﻼَ ِم، َو ِﺣ َﺴﺎﺑُ ُﻬ ْﻢ َﻋ َﲆ ﷲﱠِ said: "I have been ordered (by Allah) to fight against (ﷺ) Allah's Messenger the people until they testify that none has the right to be worshipped but and offer the prayers ,(ﷺ) Allah and that Muhammad is Allah's Messenger perfectly and give the obligatory charity, so if they perform that, then they save their lives and property from me except for Islamic laws and then their reckoning (accounts) will be done by Allah." 1 p.g.