Visual Gene Expression Reveals a Cone to Rod Developmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAT Vertebradosgt CDC CECON USAC 2019

Catálogo de Autoridades Taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala CDC-CECON-USAC 2019 Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Este documento fue elaborado por el Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) del Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala, 2019 Textos y edición: Manolo J. García. Zoólogo CDC Primera edición, 2019 Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala ISBN: 978-9929-570-19-1 Cita sugerida: Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon]. (2019). Catálogo de autoridades taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala (Documento técnico). Guatemala: Centro de Datos para la Conservación [CDC], Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon], Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala [Usac]. Índice 1. Presentación ............................................................................................ 4 2. Directrices generales para uso del CAT .............................................. 5 2.1 El grupo objetivo ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Categorías taxonómicas ......................................................... 5 2.3 Nombre de autoridades .......................................................... 5 2.4 Estatus taxonómico -

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

New Insights on the Sister Lineage of Percomorph Fishes with an Anchored Hybrid Enrichment Dataset

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 110 (2017) 27–38 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev New insights on the sister lineage of percomorph fishes with an anchored hybrid enrichment dataset ⇑ Alex Dornburg a, , Jeffrey P. Townsend b,c,d, Willa Brooks a, Elizabeth Spriggs b, Ron I. Eytan e, Jon A. Moore f,g, Peter C. Wainwright h, Alan Lemmon i, Emily Moriarty Lemmon j, Thomas J. Near b,k a North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC, USA b Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA c Program in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA d Department of Biostatistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06510, USA e Marine Biology Department, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, TX 77554, USA f Florida Atlantic University, Wilkes Honors College, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA g Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, Fort Pierce, FL 34946, USA h Department of Evolution & Ecology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA i Department of Scientific Computing, Florida State University, 400 Dirac Science Library, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA j Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, 319 Stadium Drive, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA k Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: Percomorph fishes represent over 17,100 species, including several model organisms and species of eco- Received 12 April 2016 nomic importance. Despite continuous advances in the resolution of the percomorph Tree of Life, resolu- Revised 22 February 2017 tion of the sister lineage to Percomorpha remains inconsistent but restricted to a small number of Accepted 25 February 2017 candidate lineages. -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2019-12-02T14:11:16Z Supplementary Information

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Inclusion of jellyfish in 30þ years of Ecopath with Ecosim models Author(s) Lamb, Philip D.; Hunter, Ewan; Pinnegar, John K.; Doyle, Thomas K.; Creer, Simon; Taylor, Martin I. Publication date 2019-10-09 Original citation Lamb, P. D., Hunter, E., Pinnegar, J. K., Doyle, T. K., Creer, S. and Taylor, M. I. (2019) 'Inclusion of jellyfish in 30+ years of Ecopath with Ecosim models', ICES Journal of Marine Science, fsz165. (10pp.) DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fsz165 Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/advance- version article/doi/10.1093/icesjms/fsz165/5584405 http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsz165 Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © International Council for the Exploration of the Sea 2019. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/8871 from Downloaded on 2019-12-02T14:11:16Z Supplementary information Supplementary table 1 Taxonomic groups listed as jellyfish prey in the models -

Larvae and Juveniles of the Deepsea “Whalefishes”

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2001 Records of the Australian Museum (2001) Vol. 53: 407–425. ISSN 0067-1975 Larvae and Juveniles of the Deepsea “Whalefishes” Barbourisia and Rondeletia (Stephanoberyciformes: Barbourisiidae, Rondeletiidae), with Comments on Family Relationships JOHN R. PAXTON,1 G. DAVID JOHNSON2 AND THOMAS TRNSKI1 1 Fish Section, Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] [email protected] 2 Fish Division, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT. Larvae of the deepsea “whalefishes” Barbourisia rufa (11: 3.7–14.1 mm nl/sl) and Rondeletia spp. (9: 3.5–9.7 mm sl) occur at least in the upper 200 m of the open ocean, with some specimens taken in the upper 20 m. Larvae of both families are highly precocious, with identifiable features in each by 3.7 mm. Larval Barbourisia have an elongate fourth pelvic ray with dark pigment basally, notochord flexion occurs between 6.5 and 7.5 mm sl, and by 7.5 mm sl the body is covered with small, non- imbricate scales with a central spine typical of the adult. In Rondeletia notochord flexion occurs at about 3.5 mm sl and the elongate pelvic rays 2–4 are the most strongly pigmented part of the larvae. Cycloid scales (here reported in the family for the first time) are developing by 7 mm; these scales later migrate to form a layer directly over the muscles underneath the dermis. By 7 mm sl there is a unique organ, here termed Tominaga’s organ, separate from and below the nasal rosette, developing anterior to the eye. -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

XIV. Appendices

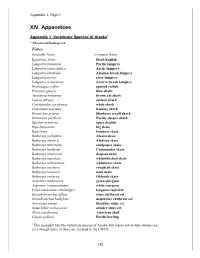

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Order MYCTOPHIFORMES NEOSCOPELIDAE Horizontal Rows

click for previous page 942 Bony Fishes Order MYCTOPHIFORMES NEOSCOPELIDAE Neoscopelids By K.E. Hartel, Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA and J.E. Craddock, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Massachusetts, USA iagnostic characters: Small fishes, usually 15 to 30 cm as adults. Body elongate with no photophores D(Scopelengys) or with 3 rows of large photophores when viewed from below (Neoscopelus).Eyes variable, small to large. Mouth large, extending to or beyond vertical from posterior margin of eye; tongue with photophores around margin in Neoscopelus. Gill rakers 9 to 16. Dorsal fin single, its origin above or slightly in front of pelvic fin, well in front of anal fins; 11 to 13 soft rays. Dorsal adipose fin over end of anal fin. Anal-fin origin well behind dorsal-fin base, anal fin with 10 to 14 soft rays. Pectoral fins long, reaching to about anus, anal fin with 15 to 19 rays.Pelvic fins large, usually reaching to anus.Scales large, cycloid, and de- ciduous. Colour: reddish silvery in Neoscopelus; blackish in Scopelengys. dorsal adipose fin anal-fin origin well behind dorsal-fin base Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Large adults of Neoscopelus usually benthopelagic below 1 000 m, but subadults mostly in midwater between 500 and 1 000 m in tropical and subtropical areas. Scopelengys meso- to bathypelagic. No known fisheries. Remarks: Three genera and 5 species with Solivomer not known from the Atlantic. All Atlantic species probably circumglobal . Similar families in occurring in area Myctophidae: photophores arranged in groups not in straight horizontal rows (except Taaningichthys paurolychnus which lacks photophores). Anal-fin origin under posterior dorsal-fin anal-fin base. -

A Checklist of the Fishes of the Monterey Bay Area Including Elkhorn Slough, the San Lorenzo, Pajaro and Salinas Rivers

f3/oC-4'( Contributions from the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories No. 26 Technical Publication 72-2 CASUC-MLML-TP-72-02 A CHECKLIST OF THE FISHES OF THE MONTEREY BAY AREA INCLUDING ELKHORN SLOUGH, THE SAN LORENZO, PAJARO AND SALINAS RIVERS by Gary E. Kukowski Sea Grant Research Assistant June 1972 LIBRARY Moss L8ndillg ,\:Jrine Laboratories r. O. Box 223 Moss Landing, Calif. 95039 This study was supported by National Sea Grant Program National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration United States Department of Commerce - Grant No. 2-35137 to Moss Landing Marine Laboratories of the California State University at Fresno, Hayward, Sacramento, San Francisco, and San Jose Dr. Robert E. Arnal, Coordinator , ·./ "':., - 'I." ~:. 1"-"'00 ~~ ~~ IAbm>~toriesi Technical Publication 72-2: A GI-lliGKL.TST OF THE FISHES OF TtlE MONTEREY my Jl.REA INCLUDING mmORH SLOUGH, THE SAN LCRENZO, PAY-ARO AND SALINAS RIVERS .. 1&let~: Page 14 - A1estria§.·~iligtro1ophua - Stone cockscomb - r-m Page 17 - J:,iparis'W10pus." Ribbon' snailt'ish - HE , ,~ ~Ei 31 - AlectrlQ~iu.e,ctro1OphUfi- 87-B9 . .', . ': ". .' Page 31 - Ceb1diehtlrrs rlolaCewi - 89 , Page 35 - Liparis t!01:f-.e - 89 .Qhange: Page 11 - FmWulns parvipin¢.rl, add: Probable misidentification Page 20 - .BathopWuBt.lemin&, change to: .Mhgghilu§. llemipg+ Page 54 - Ji\mdJ11ui~~ add: Probable. misidentifioation Page 60 - Item. number 67, authOr should be .Hubbs, Clark TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 AREA OF COVERAGE 1 METHODS OF LITERATURE SEARCH 2 EXPLANATION OF CHECKLIST 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 TABLE 1