Cavity-Adoption and the Evolution of Coloniality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P0455-P0459.Pdf

The Condor 101:455-459 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1999 BOOK REVIEWS Social Influences on Vocal Development.- Why read the rest of the book if the main themes Charles T Snowdon and Mat-tine Hausberger, eds. are already discussed in the introduction? I believe it 1997. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. is worth it, not only to check the statements of the ix + 351 pp. ISBN 0521 49526 1. $95.00 (cloth). editors. All the articles are fine reviews of a given At least in certain aspects, this book is a referee’s field, written by experts. Doug Nelson provides a very dream: not only do the editors provide short summaries good account of the state of the art in song learning in their introduction of the 16 articles making up this theory, and as I expressed above, I fully agree with his volume, they also inform the reader about the main claim that the two stage nature of song learning is still general conclusions that can be drawn from those ar- not fully understood or accepted by other researchers ticles. According to Snowdon and Hausberger, there of the field. are five central themes that arc treated in almost all Luis Baptista and Sandra Gaunt provide a very com- contributions. The first and main theme is the claim petent review on social interaction and vocal devel- that vocal learning has more aspects than learning to opment in birds. As ever, there is a wealth of findings produce sounds. It is also necessary to learn how to from the lab and from the field included in their re- use and comprehend vocalizations. -

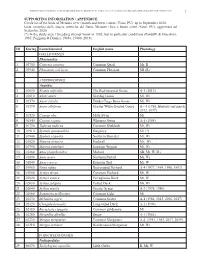

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Leptosomiformes ~ Trogoniformes ~ Bucerotiformes ~ Piciformes

Birds of the World part 6 Afroaves The core landbirds originating in Africa TELLURAVES: AFROAVES – core landbirds originating in Africa (8 orders) • ORDER ACCIPITRIFORMES – hawks and allies (4 families, 265 species) – Family Cathartidae – New World vultures (7 species) – Family Sagittariidae – secretarybird (1 species) – Family Pandionidae – ospreys (2 species) – Family Accipitridae – kites, hawks, and eagles (255 species) • ORDER STRIGIFORMES – owls (2 families, 241 species) – Family Tytonidae – barn owls (19 species) – Family Strigidae – owls (222 species) • ORDER COLIIFORMES (1 family, 6 species) – Family Coliidae – mousebirds (6 species) • ORDER LEPTOSOMIFORMES (1 family, 1 species) – Family Leptosomidae – cuckoo-roller (1 species) • ORDER TROGONIFORMES (1 family, 43 species) – Family Trogonidae – trogons (43 species) • ORDER BUCEROTIFORMES – hornbills and hoopoes (4 families, 74 species) – Family Upupidae – hoopoes (4 species) – Family Phoeniculidae – wood hoopoes (9 species) – Family Bucorvidae – ground hornbills (2 species) – Family Bucerotidae – hornbills (59 species) • ORDER PICIFORMES – woodpeckers and allies (9 families, 443 species) – Family Galbulidae – jacamars (18 species) – Family Bucconidae – puffbirds (37 species) – Family Capitonidae – New World barbets (15 species) – Family Semnornithidae – toucan barbets (2 species) – Family Ramphastidae – toucans (46 species) – Family Megalaimidae – Asian barbets (32 species) – Family Lybiidae – African barbets (42 species) – Family Indicatoridae – honeyguides (17 species) – Family -

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N. and Kimball, R. T. 2016. Re-evaluating the distribution of cooperative breeding in birds: is it tightly linked with altriciality? – J. Avian Biol. doi: 10.1111/jav.00869 Supplementary material Appendix 1. Table A1. The characteristics of the 9993 species based on Jetz et al. (2012) Order Species Criteria1 Developmental K K+S K+S+I LB Mode ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter albogularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter badius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter bicolor 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brachyurus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brevipes 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter butleri 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter castanilius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chilensis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chionogaster 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cirrocephalus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter collaris 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cooperii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythrauchen 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythronemius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythropus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter fasciatus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter francesiae 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gentilis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter griseiceps 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gundlachi 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter haplochrous 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henicogrammus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henstii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter imitator 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES -

Silvery-Cheeked Hornbill Bycanistes Brevis

Silvery-cheeked Hornbill Bycanistes brevis Class: Aves Order: Bucerotiformes Family: Bucerotidae Characteristics: A fairly large bird with a cream-colored, lightweight casque (“horn”) on top of its beak. The head has silvery-grey feathers (hence the name) and the rest of the body is covered with black or white feathers. In males, the casque is larger than the females. Otherwise they are quite similar. Behavior: They usually live in pairs and, as they are fairly gregarious, will sometimes roost in flocks of several hundred individuals (Beauty of Birds). They have a fairly wide range through which they fly long distances feeding on fruits and small birds in flight. They return to their tree roost at night. Reproduction: They breed in the African spring (September and October). The female finds a cavity and, with the male’s help, seals herself in leaving a small hole through which he feeds her regurgitated fruit. She lays a clutch of 1-3 eggs which hatch following a 40-day incubation period (Oiseaux Birds). Diet: Wild: mainly fruits but will also eat insects, small birds, rodents, small reptiles, centipedes Zoo: softbill, fruit/veg mix, hardboiled egg, dog food and parrot pellets Conservation: The population appears to be quite stable and has a large range, however their numbers seem to be declining in Zimbabwe (Biodiversity Explorer). FYI: The hornbill is one of the few birds that have eyelashes to shield them from sun and dust (Pittsburg Zoo). . -

Preliminary Survey on Relative Diversity and Residential Status of Avifauna in District Karnal, Haryana ( India)

International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research and Management, Volume 4 Issue 6, June 2019 www.ijasrm.com ISSN 2455-6378 Preliminary Survey on Relative Diversity and Residential Status of Avifauna in district Karnal, Haryana ( India). Parveen Kumar Vats Associate Professor, Department of Zoology,Pt. C.L.S. Govt. College Karnal Karnal, Haryana, India Abstract transferring nutrients and spores from one place to The present study was conducted in another during their migration and local movements different sites of district Karnal, Haryana (India) (Niemi, 1985). Birds show variations greatly in their from May 2017 to April 2019. A total of 122 bird diversity, habitats, abundance and distribution species were observed by using line and point count throughout the globe. They have usually more method. These 122 bird species belongs to 17 diversity in tropics than others regions like different orders and maximum bird species were temperate, alpine or polar. Their habitat preferences observed in order Passeriformes (48) followed by are more or less specialized. They occupy higher order Pelecaniformes (14). Accipitridae and trophic levels in food webs. They also vary in their Ardeidae were two families in which equal number abundance because some species occur in large of bird species (8) were observed. A total of 88 bird numbers while others are represented by few species out of 122 observed avian species were individuals only. Some avian species have small resident, 29 bird species were winter migrants and 5 breeding ranges in some particular region whereas bird species were observed only in summer during others travel long distance and annual migrations the present study. -

The Origin and Diversification of Birds

Current Biology Review The Origin and Diversification of Birds Stephen L. Brusatte1,*, Jingmai K. O’Connor2,*, and Erich D. Jarvis3,4,* 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, King’s Buildings, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA 4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.B.), [email protected] (J.K.O.), [email protected] (E.D.J.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003 Birds are one of the most recognizable and diverse groups of modern vertebrates. Over the past two de- cades, a wealth of new fossil discoveries and phylogenetic and macroevolutionary studies has transformed our understanding of how birds originated and became so successful. Birds evolved from theropod dino- saurs during the Jurassic (around 165–150 million years ago) and their classic small, lightweight, feathered, and winged body plan was pieced together gradually over tens of millions of years of evolution rather than in one burst of innovation. Early birds diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous, becoming capable fliers with supercharged growth rates, but were decimated at the end-Cretaceous extinction alongside their close dinosaurian relatives. After the mass extinction, modern birds (members of the avian crown group) explosively diversified, culminating in more than 10,000 species distributed worldwide today. Introduction dinosaurs Dromaeosaurus albertensis or Troodon formosus.This Birds are one of the most conspicuous groups of animals in the clade includes all living birds and extinct taxa, such as Archaeop- modern world. -

Early Paleocene Landbird Supports Rapid Phylogenetic and Morphological Diversification of Crown Birds After the K–Pg Mass Extinction

Early Paleocene landbird supports rapid phylogenetic and morphological diversification of crown birds after the K–Pg mass extinction Daniel T. Ksepkaa,1, Thomas A. Stidhamb, and Thomas E. Williamsonc aBruce Museum, Greenwich, CT 06830; bKey Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China; and cNew Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque, NM 87104 Edited by Gareth Dyke, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, and accepted by Editorial Board Member David Jablonski June 7, 2017 (received for review January 9, 2017) Evidence is accumulating for a rapid diversification of birds follow- Other fossils defy precise classification, but none can be con- ing the K–Pg extinction. Recent molecular divergence dating studies vincingly assigned to any clade within crown Aves, and only one suggest that birds radiated explosively during the first few million taxon identified from the Maastrichtian of North America appears years of the Paleocene; however, fossils from this interval remain to cross the K–Pg boundary (5, 8). Even fewer early Paleocene poorly represented, hindering our understanding of morphological birds are known, a situation exacerbated by the fact that strati- and ecological specialization in early neoavian birds. Here we report graphic resolution remains poor for many marine birds from the a small fossil bird from the Nacimiento Formation of New Mexico, Hornerstown Formation of New Jersey and terrestrial birds from constrained to 62.221–62.517 Ma. This partial skeleton represents the “Bug Creek” sequence in Montana, each of which contains a the oldest arboreal crown group bird known. -

Cjz 2016 0142 Supplement 3.Pdf

Supplementary Figures S1 - S11 PC1 (−) PC1 mean PC1 (+) 30 Figure S1. Shape of eggs associated with 10 20 50 O1 different regions of specific principal components: 5 10 O1 minimal, mean, and maximum. O1 0 0 0 O2 O O2 O O2 O O3 O3 O3 −5 −50 −20 −10 −15 −100 −40 −100 −50 0 50 100 −30 −10 0 10 20 30 −15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15 PC2 (−) PC2 mean PC2 (+) 40 20 20 20 O1 O1 10 O1 0 0 O2 O3O O2 O 0 O2 O O3 −20 O3 −10 −20 −40 −20 −40 −60 −30 −40 −20 0 20 40 −40 −20 0 20 40 −20 −10 0 10 20 PC3 (−) PC3 mean PC3 (+) 30 20 20 O1 20 O1 10 10 O1 0 0 0 O2 O O2 O O2 O O3 O3 O3 −10 −20 −20 −20 −40 −30 −40 −40 −20 0 20 40 −20 0 20 −30 −20 −10 0 10 20 30 15 Figure S2. Position of orders in the space of PC1 and PC2. Shape of eggs correspond to specific parts of PCs. 10 Loadings are shown at the lower left corner of figure. All orders 5 ACCIPITRIFORMES ANSERIFORMES APODIFORMES BUCEROTIFORMES CAPRIMULGIFORMES 0 CARIAMIFORMES CHARADRIIFORMES CICONIIFORMES COLUMBIFORMES PC2 CORACIIFORMES −5 CUCULIFORMES EURYPYGIFORMES FALCONIFORMES GALLIFORMES GAVIIFORMES GRUIFORMES −10 OTIDIFORMES PASSERIFORMES PELECANIFORMES PHOENICOPTERIFORMES PICIFORMES −15 PODICIPEDIFORMES PROCELLARIIFORMES PSITTACIFORMES PTEROCLIDIFORMES SPHENISCIFORMES −20 STRIGIFORMES SULIFORMES −40 −30 −20 −10 0 10 20 PC1 Icz LD PC2 Ilz Iiz PC1 15 30 Figure S3. Position of orders with altricial developmental mode in the space −30 of PC1 and PC2. -

Brains and Birdsong

Chapter 8 Brains and birdsong ERICH D. JARVIS INTRODUCTION contrasts and their underlying principles holds promise of new and fundamental insights into The special brain structures for singing, and how brains make learning possible. The discovery learning how to sing, were discovered in 1976. of similar sets of brain structures in parrots and Since then, with still growing momentum, there hummingbirds throws new light on how brain has been a wealth of fascinating discoveries on structures for vocal learning have evolved. The the structure, function, and evolution of the shared features imply that there are strong brains of birds, especially those that engage in epigenetic constraints placed on the brain and vocal learning. Less than half of all birds possess behavior during evolution, and suggest that the ability to learn and reproduce new sounds. perhaps humans evolved somewhat similar brain These vocal learners, parrots, hummingbirds, and structures for speech and singing. Although the songbirds belong to only 3 of the 23 major bird cognitive side of song learning hardly bears groups. They have the necessary forebrain comparison with human speech, ‘bird-brained’ anatomy for producing learned vocalizations. All need no longer be a pejorative. If a parrot imitates other birds use only basal brain structures for its own and other species’ sounds so readily and vocal production and their vocalizations are a child can hardly be prevented from learning to innate, and genetically inherited from their speak, how is it that a chimpanzee does neither? parents. The answer perhaps lies in the fact that no brain Of the birds that are vocal learners, most is structures have been found in chimpanzees known about songbirds, especially the canary equivalent to those present in songbirds and and the zebra finch. -

Acoustic Behavior and Ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus Mocinno, a Flagship Tropical Bird Species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler

Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler To cite this version: Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler. Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species. Biodiversity and Ecology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2019. English. NNT : 2019MNHN0001. tel-02048769 HAL Id: tel-02048769 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02048769 Submitted on 25 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2019 N°attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : écologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Pablo BOLAÑOS Le 18 janvier 2019 Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Sous la direction de : Dr. Jérôme SUEUR, Maître de Conférences, MNHN Dr. Thierry AUBIN, Directeur de Recherche, Université Paris Saclay JURY: Dr. Márquez, Rafael Senior Researcher, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid Rapporteur Dr. -

Developmental Origins of Mosaic Evolution in the Avian Cranium

Developmental origins of mosaic evolution in the SEE COMMENTARY avian cranium Ryan N. Felicea,b,1 and Anjali Goswamia,b,c aDepartment of Genetics, Evolution, and Environment, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5DB, United Kingdom; and cDepartment of Earth Sciences, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved December 1, 2017 (received for review September 18, 2017) Mosaic evolution, which results from multiple influences shaping genes. For example, manipulating the expression of Fgf8 generates morphological traits and can lead to the presence of a mixture of correlated responses in the growth of the premaxilla and palatine ancestral and derived characteristics, has been frequently invoked in in archosaurs (11). Similarly, variation in avian beak shape and describing evolutionary patterns in birds. Mosaicism implies the size is regulated by two separate developmental modules (7). hierarchical organization of organismal traits into semiautonomous Despite the evidence for developmental modularity in the avian subsets, or modules, which reflect differential genetic and develop- skull, some studies have concluded that the cranium is highly in- mental origins. Here, we analyze mosaic evolution in the avian skull tegrated (i.e., not subdivided into semiautonomous modules) (9, using high-dimensional 3D surface morphometric data across a 10, 12). In light of recent evidence that diversity in beak mor- broad phylogenetic sample encompassing nearly all extant families. phology may not be shaped by dietary factors (12), it is especially We find that the avian cranium is highly modular, consisting of seven critical to investigate other factors that shape the evolution of independently evolving anatomical regions.