Antwerp Jewry Today Jacques Gutwirth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ja Hobson's Approach to International Relations

J.A. HOBSON'S APPROACH TO INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: AN EXPOSITION AND CRITIQUE David Long Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy in International Relations at the London School of Economics. UMI Number: U042878 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U042878 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis argues that Hobson’s approach to international relations coheres around his use of the biological analogy of society to an organism. An aspect of this ‘organic analogy’ - the theory of surplus value - is central to Hobson’s modification of liberal thinking on international relations and his reformulated ‘new liberal internationalism’. The first part outlines a theoretical framework for Hobson’s discussion of international relations. His theory of surplus value posits cooperation as a factor in the production of value understood as human welfare. The organic analogy links this theory of surplus value to Hobson’s holistic ‘sociology’. Hobson’s new liberal internationalism is an extension of his organic theory of surplus value. -

COMMUNICATION and STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT in ENVIRONMENTAL REMEDIATION PROJECTS the Following States Are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NW-T-3.5 Basic Communication and Principles Stakeholder Involvement Objectives in Environmental Remediation Projects Guides Technical Reports INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA ISBN 978–92–0–145210–8 ISSN 1995–7807 13-49251_PUB1629_cover.indd 1-2 2014-05-21 09:25:53 IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES PUBLICATIONS STRUCTURE OF THE IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES Under the terms of Articles III.A and VIII.C of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to foster the exchange of scientific and technical information on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. The publications in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series provide information in the areas of nuclear power, nuclear fuel cycle, radioactive waste management and decommissioning, and on general issues that are relevant to all of the above mentioned areas. The structure of the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series comprises three levels: 1 — Basic Principles and Objectives; 2 — Guides; and 3 — Technical Reports. The Nuclear Energy Basic Principles publication describes the rationale and vision for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Objectives publications explain the expectations to be met in various areas at different stages of implementation. Nuclear Energy Series Guides provide high level guidance on how to achieve the objectives related to the various topics and areas involving the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Technical Reports provide additional, more detailed information on activities related to the various areas dealt with in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series. The IAEA Nuclear Energy Series publications are coded as follows: NG — general; NP — nuclear power; NF — nuclear fuel; NW — radioactive waste management and decommissioning. -

NEWSLETTER Embassy of Romania in Belgium

NEWSLETTER Embassy of R omania in Belgium No. 4 October-Dece mber 2013 omania in Belgium The entire team of the Embassy of Romania in Belgium wishes to all readers of our Newsletter, partners and friends of Romania, season’s greetings and Happy New Year 2014! FORUM FOR DESCENTRALIZED COOPERATION In the three plenary sessions of the Forum, Belgium and BETWEEN ROMANIA AND BELGIUM Romania representatives made presentations regarding The 4th edition of the Forum of decentralized cooperation the stage and objectives of the process of descentralization between Romania and Belgium took place in Leuven, 25- and expressed points of view 27 October 2013. The Forum was organized by the on concrete modalities of associations Actie Dorpen Roemenie (ADR), Operation stimulating cooperation Villages Roumains (OVR) and PVR (Parteneriat Villages initiatives at the local and Roumains), with the support of the Embassy of Romania in Belgium, the Embassy of Belgium to Bucharest and the regional level, including by Province of the Flemish Brabant. means of public policies in key The event was hosted by the cooperation areas of both countries. Province of the Flemish The 2013 edition of the Forum included an important Brabant and enjoyed the business dimension and offered the opportunity for participation of exploring opportunities for initiating partnerships representatives of local and provincial authorities from between Romanian and Belgian private companies. The both countries, as well as Business to Business meeting benefited from the presence representatives of NGOs, of Mr. Leonard Orban, ex-European Commissioner and professional associations, universities and research minister for European affairs, as keynote speaker on how institutes, companies interested in the decentralized to access European funds for local projects in Romania. -

L. T. Hobhouse and J. A. Hobson

Two years before the Labour Party victory of 1997, Tony Blair made a seminal speech L. T. HOBHOUSE AND J. A. HOBSON: to the Fabian Society in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary ThE NEW LIBERAL INFLUENCE ON ThiRD WAY idEAS of the 1945 Labour election victory. The speech was a major media event because it was a defining moment for New Labour ‘modernisers’. They were seeking to move the party from its socialist history on to ‘new’ political and ideological ground – as well as reap the tactical electoral benefits they felt could be gained by such a shift. Blair used the speech to pronounce himself ‘proud’ to be a ‘democratic socialist’ while redefining socialism to create ‘social-ism’. More relevant here, as seen above, was Blair’s reiteration of British political history from this revised New Labour position. Dr Alison Holmes examines New Liberal influences on Blair’s ‘Third Way’. 16 Journal of Liberal History 55 Summer 2007 L. T. HOBHOUSE AND J. A. HOBSON: ThE NEW LIBERAL INFLUENCE ON ThiRD WAY idEAS lair listed both L. T exercise it. So they argued for the New Liberal ideas of writers Hobhouse and J. A. collective action, including such as Hobhouse and Hobson Hobson amongst the state action, to achieve positive that were to carry through to intellectual corner- freedom, even if it infringed the modern interpretation of the stones of both New traditional laissez-faire liberal Third Way. BLiberalism and New Labour – orthodoxy … They did not call later termed the Third Way: themselves socialists, though Hobhouse coined the term J. -

Ethics Content

Ethics Content I Introduction to Ethics Unit-1 Nature and Scope of Ethics Unit-2 Importance and Challenges of Ethics Unit-3 Ethics in the History of Indian Philosophy Unit-4 Ethics in the History of Western Philosophy II Ethical Foundations Unit-1 Human Values Unit-2 Human Virtues Unit-3 Human Rights Unit-4 Human Duties III Applied Ethics Unit-1 International Ethics Unit-2 Bioethics Unit-3 Environmental Ethics Unit-4 Media Ethics IV Current Ethical Debates Unit-1 Natural Moral Law Unit-2 Deontology and Moral Responsibility Unit-3 Discourse Ethics Unit-4 Social Institutions UNIT 1 NATURE AND SCOPE OF ETHICS Nature and Scope of Ethics Contents 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Moral Intuitionism 1.3 Human Person in Search of Himself/Herself 1.4 Love and the Moral Precepts 1.5 The Dynamics of Morality 1.6 The Constant and the Variable in Morality 1.7 Let Us Sum Up 1.8 Key Words 1.9 Further Readings and References 1.0 OBJECTIVES This unit aims at introducing the students to the philosophical need for Ethics starting from a brief discussion of Moral law and how the human person in his or her process of growth intuits the ethical principles. Discussions pertaining to the dynamics of morality is undertaken to show how on the one hand new situations call for new responses from moral point of view and on the other hand certain fundamentals of ethics remain the same in so far as there is something of a common human nature adequately understood. -

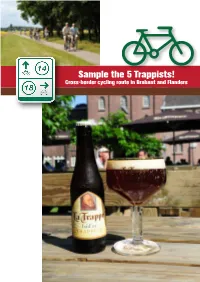

Taste Abbeyseng

Sample the 5 Trappists! Cross-border cycling route in Brabant and Flanders The Trappist region The Trappist region ‘The Trappists’ are members of the Trappist region; The Trappist order. This Roman Catholic religious order forms part of the larger Cistercian brotherhood. Life in the abbey has as its motto “Ora et Labora “ (pray and work). Traditional skills form an important part of a monk’s life. The Trappists make a wide range of products. The most famous of these is Trappist Beer. The name ‘Trappist’ originates from the French La Trappe abbey. La Trappe set the standards for other Trappist abbeys. The number of La Trappe monks grew quickly between 1664 and 1670. To this today there are still monks working in the Trappist brewerys. Trappist beers bear the label "Authentic Trappist Product". This label certifies not only the monastic origin of the product but also guarantees that the products sold are produced according the traditions of the Trappist community. More information: www.trappist.be Route booklet Sample the 5 Trappists Sample the 5 Trappists! Experience the taste of Trappist beers on this unique cycle route which takes you past 5 different Trappist abbeys in the provinces of North Brabant, Limburg and Antwerp. Immerse yourself in the life of the Trappists and experience the mystical atmosphere of the abbeys during your cycle trip. Above all you can enjoy the renowned Brabant and Flemish hospitality. Sample a delicious Trappist to quench your thirst or enjoy the beautiful countryside and the towns and villages with their charming street cafes and places to stay overnight. -

A Record of Events and Trends in American and World Jewish Life

American Jewish Year Book 1960 A Record of Events and Trends in American and World Jewish Life AMERICAN JFAVISH COMMITTEE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA $6.00 N ITS 61 YEARS OF PUBLICATION, the AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK has provided a unique chronicle of Jewish life in the United States and throughout the world. Appearing at a time when anti-Semitism and neo-Nazism have shocked the world, when tensions and antagonisms in the Middle East are flaring anew and the Jewish commu- nities of North Africa are faced with a rising tide of Arab nationalism, this lat- est volume once again colors in the in- dispensable background for an intelhV gent reading of today's headlines. The present volume also offers inten- sive examination of key issues in the United States and summaries of major programs in American Jewish life. An article based on the first National Study of Jewish Education describes the achievements and failures of Jewish edu- cation in America, gives statistical data, and analyzes its many problems. Another article reports the first find- ings of the National Jewish Cultural Study — which includes surveys of ar- chives, scholarships, research, publica- tions and Jewish studies in secular insti- tutions of higher learning. In addition, there are incisive analyses of civil rights and civil liberties in the United States; recent developments in church-state relationships; anti-Jewish agitation; Jewish education, fund rais- ing, the Jewish center movement, Jew- ish social welfare, and other communal programs. The present volume also answers basic questions about Jews in America; popu- (Continued on back flap) 4198 * * • * * * * * * jI AMERICAN JEWISH I YEAR BOOK * * •I* >j» AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK ADVISORY COMMITTEE Oscar Handlin, Chairman Salo W. -

PLANHEAT's Satellite-Derived Heating and Cooling

Letter PLANHEAT’s Satellite-Derived Heating and Cooling Degrees Dataset for Energy Demand Mapping and Planning Panagiotis Sismanidis 1,*, Iphigenia Keramitsoglou 1, Stefano Barberis 2, Hrvoje Dorotić 3, Benjamin Bechtel 4 and Chris T. Kiranoudis 1,5 1 Institute for Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens, 15236 Athens, Greece 2 Corporate Research & Development Division, RINA Consulting S.p.A., 16145 Genova, Italy 3 Department of Energy, Power Engineering and Environment, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Naval Architecture, University of Zagreb, 10002 Zagreb, Croatia 4 Department of Geography, Ruhr-University Bochum, 44807 Bochum, Germany 5 School of Chemical Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, 15780 Athens, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +20-210-810-9167 Received: date; Accepted: date; Published: 30 August 2019 Abstract: The urban heat island (UHI) effect influences the heating and cooling (H&C) energy demand of buildings and should be taken into account in H&C energy demand simulations. To provide information about this effect, the PLANHEAT integrated tool—which is a GIS-based, open- source software tool for selecting, simulating and comparing alternative low-carbon and economically sustainable H&C scenarios—includes a dataset of 1 × 1 km hourly heating and cooling degrees (HD and CD, respectively). HD and CD are energy demand proxies that are defined as the deviation of the outdoor surface air temperature from a base temperature, above or below which a building is assumed to need heating or cooling, respectively. PLANHEAT’s HD and CD are calculated from a dataset of gridded surface air temperatures that have been derived using satellite thermal data from Meteosat-10 Spinning Enhanced Visible and Near-Infrared Imager (SEVIRI). -

1 Philosophy at University College London

1 Philosophy at University College London: Part 1: From Jeremy Bentham to the Second World War Talk to Academic Staff Common Room Society, April 2006 Jonathan Wolff I’m quite often asked to give talks but I’m rarely asked to talk about the philosophy department. In fact I can only remember being asked to do this once before: to College Council very soon after Malcolm Grant was appointed as Provost. On that occasion I decided to tell a cautionary tale: painting a picture of the brilliance of the department in the late 1970s – second in the country only to the very much larger department at Oxford; how it was all ruined in the early 1980s by a wave of cost- cutting measures in which all the then internationally known members of the department left; and how it has taken twenty-five years to come close to recovery. This seemed to go down well on the day, but I can’t say that I won the longer term argument about the imprudence of cost-cutting. For this talk I was, at first, at a bit of a loss to know what to talk about. One possibility would be to try to describe the research that currently takes place in the department. But this idea didn’t appeal. Philosophers tend to work on their own, and so we don’t have research groups, as such, or collective projects. We have 15 members of the department, each engaged on their own research. Also, every time I try to summarize their work my colleagues tell me that I have misunderstood it. -

The Antwerp Industrial Market

THE ANTWERP INDUSTRIAL MARKET Trends and outlook - 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 7 THE ANTWERP INDUSTRIAL MARKET 10 CURRENT MARKET DYNAMICS LOGISTICS 14 SEMI-INDUSTRIAL 17 ANTWERP INDUSTRIAL INVESTMENT MARKET 21 CONTACTS 22 The city is located in the heart“ of one of the most concentrated urban areas in Belgium and Europe CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD INTRODUCTION The city of Antwerp is the capi- tal of the Antwerp province and is second largest city in Belgium. Antwerp functions as the main economic motor of the Flemish re- The city is located in the heart of gion but is also an important international business epicentre for one of the most concentrated ur- certain industries. Antwerp is the second largest portal city in Eu- ban areas in Belgium and Europe, rope, the world capital in the diamond industry and Europe’s largest forming a triangle with Brussels petrochemical cluster. Moreover, the city has become an important and Ghent where most of Bel- fashion centre as well and is home to flagship stores and branches gium’s economic and industrial from all major domestic and international retailers. activities are located. Antwerp benefits from a decent road network but accessibility during peak time is often problematic due to heavy traffic conges- tion on the city ring road and the highways connecting the city. The railway infrastructure is well-established with direct connections to almost all major Belgian cities and some neighbouring capitals. Fi- ANTWERP nally, Antwerp also benefits from an international airport near the centre of the city. DEFINITIONS Logistics buildings Buildings designed for logistics activities. -

CONTENTS Proposed Electoral Reform in Israel a Brief Survey Of

VOLUME XXXIII NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 1991 CONTENTS Proposed Electoral Reform in Israel AVRAHAM BRICHTA A Brief Survey of Present-Day Karaite Communities in Europe EMANUELA TREVISAN SEMI Synagogue Marriages in Britain in the 1g8os MARLENA SCHMOOL Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism GEOFFREY ALDERMAN Book Reviews Chronicle Editor: J udith Freedman OBJECTS. AN:b SPONSORSHIP C>F THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCI.OLOGY The Jewish Journal ofSociology was spon~rired by the Cultural Department of the World Jewish Congress from its inception in 1959 until the end of 1980. Thereafter, from the first issue of 1981 (volume 23, no. 1), the Journal has been sponsored by Maurice Freedman Research Trust Limited, which is registered as an educational charity and has as its main purposes the encouragement of· research in the sociology of the Jews and the publication ofTheJewishJournal of Sociology. The objects of the Journal remain as stated in the Editorial of the first issue in 1959: 'This Journal has been brought into being in order to provide an international vehicle for serious writing on Jewish social affairs ... Academically we address ourselves not only to sociologists, but to social scientists in general, to historians, to philosophers, and to students of comparative religion .... We should like to stress both that the Journal is editorially independent and that the opinions expressed by authors are their own responsibility.' The founding Editor of the JJS was Morris Ginsberg, and the founding Managing Editor was Maurice Freedman. Morris Ginsberg, who had been Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics, died in 1970. Maurice Freedman, who had been Professor of Social Anthropology at the London School of Economics and later at the University of Oxford, succeeded to the title of Editor in 1971, when Or Judith Freedman (who had been Assistant Editor since 1963) became Managing Editor. -

Meet in Flanders

Quirky Flanders 20 of the region’s oddest or most unexpected activities CONTENT Derek Blyth Author Quirky Flanders 2 / Walk barefoot in Limburg 12 / Discover the new Berlin landers is full of offbeat things to do. 3 / Visit a bizarre Belgian enclave 13 / Take a foodie tour in the Westhoek They can be surprising, sometimes 4 / Walk through a forest that was once 14 / Explore the dark secrets of a Fa little disturbing, but always a battlefield Brabant Castle unexpected. Most are off the beaten track, 5 / Find old Antwerp in a lost Scheldt 15 / Cycle down the golden river away from the crowds, in places that are village 16 / Sneak a look at the forbidden sometimes hard to find. 6 / Follow the Brussels street art trail sculpture 7 / Find the Bruges no one knows 17 / Stroll through eccentric You might need to ask in a local bar 8 / Take the world’s longest tram ride architecture for directions or set off on foot down a 9 / Admire the station that moved 36 18 / Take a night walk in Ghent muddy track. But it’s worth making the metres 19 / Hop on a free bike to explore effort to find them, because they tell you 10 / Wander along Mechelen’s lost river Ostend’s hinterland something about Flanders that you don’t 11 / Visit the world’s most beautiful 20 / Walk under the river in Antwerp read in the guide books or learn from chocolate shop Wikipedia. Quirky Flanders 2 WALK BAREFOOT IN LIMBURG VISIT A BIZARRE BELGIAN ENCLAVE he village of Baarle-Hertog is described as a Belgian enclave within the Nether- Tlands, but it’s a lot more complicated than that.