Aglianico from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wine, Beer and Cocktails

5oz | BTL 5oz | BTL SPARKLING PINK BRUT CREMANT D’ALSACE JOSEPH CATTIN Alsace , FRA NV………………………… 11 43 TEMPRANILLO ‘MONTECASTRILLO’ FINCA TORREMILANOS Castilla y León, SPA ‘20… 9 35 COCKTAILS WE COULDN’T *NOT* HAVE COCKTAILS. 15 60 LAMBRUSCO LINI 910 Emilia Romagna, ITA NV ………………………………………….…. 9 37 FIELD BLEND ARNOT ROBERTS CAL ’20 …………………………………………………… LIL PICK ME UP | chilled coffee, Lockhouse coffee liquor, sfumato, curaçao 11 SOME SWEET, SOME FORTIFIED, ALL TASTY PIEDMONTESE BLEND ‘FEINTS' RUTH LEWANDOWSKI Mendocino, CA ’20 ….. 16 65 VERDEJO ‘NIEVA YORK’ PET NAT MICROBIO WINES ‘20 Castilla y León SPA ……… 17 68 WNY SOUR | whiskey, lemon, simple, lambrusco float …………………….……………. 11 FLIGHT OF 3 (1OZ) $12 ‘ROSE CUVEE ZERO' RUTH LEWANDOWSKI Mendocino, CA ’20 …………………………….. (65) BUGEY-CERDON RENARDAT-FACHE Savoy, FRN ’18………………….…………………… 12 50 BUCK NASTY | rye, velvet falernum, allspice dram, lime ………………………….. 12 FRANCE PINOT NOIR ‘PROSA' MEINKLANG Burgenland AUT ‘20 ………………………………… 11 45 ROSE DOMAINE FRANCOIS CHIDAINE Loire, FRA ’19…………………………………………… 50 SAKURA FITZGERALD |lockhouse sakura gin, lemon, simple, bitters ……..…… 12 BANYULS HORS D’AGE VIEILLI EN SOSTRERA DOMAINE DU MAS BLANC FRA NV …… 12 FOAM WHITE MEINKLANG Burgenland AUT ’19 …………….…………………………………….. 58 TIBOUREN ROSE CLOS CIBONNE Provence, FRA ’18………………………………………….… 69 PEPPER LA RYE-JA | rye, vermouth, sfumato .……………………………………………….. 11 GRANCHE NOIR DOMAINE DU DERNIER BASTION, MAURY RANCIO, Roussillon, FRA ’07 ………… 10 CAVA BRUT ROSADO VIA DE LA PLATA SPA NV …………….……………………………………… 43 HIMMEL AUF ERDEN ROSE CHRISTIAN TSCHIDA AUS ’19 ……………………………………. 78 METAXA SIDE CAR | metaxa brandy, lemon, curaçao .…………………………………….. 11 RENDEZ-VOUS NO. 1 BILLECART-SALMON FRA NV …………….…………..…………………… 125 SPAIN SPRING SANGRIA | white blend, grapefruit, falernum, cap corse, aperitivo 12 CHAMPAGNE BLANC DE BLANC PIERRE MONCUIT FRA NV (375ml)…….…………..……… 50 RED SOLERA GARNATXA D’EMPORDA ESPADOL Solera, SPA NV …….……………………………. -

Working Wine Inventory

Sparkling Domestic 218 Gruet Sauvage, USA NV 39 124 Schramsberg Blanc de Blanc, CA 2013 52 104 Sokol Blosser Evolution Méthode Champenoise, USA NV 42 Champagne 113 Billecart Salmon Brut Reserve, Mareuil-sur-Ay, Marne NV 90 116 Delahaie Brut, Millésime, Epernay 2008 83 118 Egly Oriet Les Vignes de Vrigny, Brut, Premier Cru, Ambonnay NV 125 188 Gosset Brut NV 65 114 Jean Vesselle Reserve Brut, Bouzy NV 75 1014 Moutard Cepage Arbane, Bouxeuil 2008 cellar temp. 170 244 Moutard Grand Cuvee, Bouxeuil NV 65 280 Perrier-Jouët Bele Epoque, Epernay 2007 280 208 Taittinger Brut La Française, Reims NV 80 108 Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin Brut, Reims NV 100 Around the World Sparkling 120 Bisol Crede Brut, Prosecco Superiore DOCG, Valdobbiadene, ITA NV 52 229 Colet Navazos Sherry Spiked Cava, Extra Brut, Penedes, ESP 2010 75 109 San Martino Extra Dry, Prosecco DOC, Treviso, ITA NV 36 184 Domaine Perraud Le Grand Sorbier, Cremant de Borgogne, FRA NV 40 Sparkling Rosé 100 Albert Bichot Brut Rosé Crémant de Bourgogne, FRA NV 41 249 De Chanceny Brut, Crémant de Loire, FRA NV 36 131 Giro Ribot Cava Rosé, ESP NV 35 110 Lucien Albrecht Brut Rosé, Crémant d'Alsace, FRA NV 39 182 Tenuta Col Sandago Brut Rosé, Veneto, ITA 2014 44 114 Jean Vesselle Reserve Brut, Bouzy NV 75 80/20 Pinot Noir to Chardonnay with scents of green apple, lemon blossom and lightly toasted brioche. The creamy, energetic and richly textured palate effortlessly supports intricate flavors of honeysuckle, pear, almond, pie crust and orange pith. Page 1 6/25/2016 Chardonnay Washington 119 Abeja Washington State 2014 75 267 Ashen Conner Lee Vineyard, Columbia Valley 2013 75 126 Browne Columbia Valley 2014 48 101 Cht. -

Wines by the Glass

WINES BY THE GLASS ROSÉ Macari Vineyards Estate Mattituck 2016 North Fork, NY 11/36 CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING Segura Viudas Blanco Cava Brut NV Catalunya, SP 10 Btl 187ml Segura Viudas Rose Cava Brut NV Catalunya, SP 10 Btl 187ml Caviro Romio Prosecco NV Veneto, IT 10/36 I Borboni Asprinio Brut NV Campania, IT 49 Btl Ferrari Brut NV Trentino, IT 49 Ferrari Giulio Ferrari Brut Riserva del Fondatore 2002 Trentino, IT 270 Btl Champagne Philippe Gonet Brut Signature Blanc de Blancs NV Champagne, FR 40 Btl 375ml Champagne Fleury Brut Blancs de Noir Rose NV Biodynamic Champagne, FR 45 Btl 375ml La Caudrina Moscato d’Asti Piedmont, IT 10/34 500ml FROM THE TAP $9 per Glass Trebbiano/Poderi dal Nespoli/Sustainably Farmed 2016 Emilia-Romagna, IT Pinot Grigio/Venegazzu Montelvini Veneto, IT Chardonnay/Millbrook Estate/Sustainably Farmed 2014 Hudson River Valley, NY Barbera d’Alba/Cascina Pace/Sustainably Farmed 2015 Piedmont, IT Sangiovese/Poderi Dal Nespoli, Sangiovese Rubicone 2015 Emilia-Romagna, IT Merlot-Cabernet Sauvignon/Venegazzu Montelvini Veneto, IT WHITES BY THE GLASS/BOTTLE Cantina Cembra Sauvignon Blanc 2016 Trentino, IT 10/36 Figini Gavi di Gavi Cortese 2016 Piedmont, IT 12/40 Albino Armani “io” Pinot Grigio 2016 Trentino, IT 10/34 Paco y Lola Albarino 2013 Rias Baixas, SP 14/49 Suhru Riesling (Dry) 2016 Long Island, NY 11/39 Tenuta dell’ Ugolino Le Piaole “Castelli di Jesi” Verdicchio 2016 Marche, IT 10/38 Tenute Iuzzolini Ciro Bianco 2014 Calabria, IT 10/34 Marabino “Muscatedda” Moscato di Noto (Dry) 2014 Certified Organic Sicily, IT -

Discover the Alluring Wines Of

DISCOVER THE ALLURING WINES OF ITAPORTFOLIOLY BOOK l 2015 Leonardo LoCascio Selections For over 35 years, Leonardo LoCascio Selections has represented Italian wines of impeccable quality, character and value. Each wine in the collection tells a unique story about the family and region that produced it. A taste through the portfolio is a journey across Italy’s rich spectrum of geography, history, and culture. Whether a crisp Pinot Bianco from the Dolomites or a rich Aglianico from Campania, the wines of Leonardo LoCascio Selections will transport you to Italy’s outstanding regions. Table of Contents Wines of Northern Italy ............................................................................................ 1-40 Friuli-Venezia-Giulia .................................................................................................. 1-3 Doro Princic ......................................................................................................................................................................2 SUT .......................................................................................................................................................................................3 Lombardia ...................................................................................................................4-7 Barone Pizzini ..................................................................................................................................................................5 La Valle ...............................................................................................................................................................................7 -

Our Namesake, Coda Di Volpe, Comes from a Grape Only Found in Southern Italy

WINE Our namesake, Coda di Volpe, comes from a grape only found in Southern Italy. Pulled from near extinction, it is one that expresses the true landscape & vineyards of Campania. Meaning “Tail of the Fox,” Coda di Volpe has influenced our entire wine program. Some of the most dynamic wines in the world are being made & bottled from the six traditional regions of Southern Italy; Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, Calabria, Sicily & Sardinia. Just as our namesake shows us a glimpse of the past, so do the other ancient varietals we have gathered on our list. By supporting small producers & native species, we strive to represent the vibrancy of Southern Italy’s present & future. We look forward to sharing our passion for those regions in every glass we pour. indicates native varietal once on the brink of extinction aperitivio wines Produced in the method of Fino Sherry & aged in chestnut barrels for a minimum of 10 years, Vernaccia di Oristano are complex & extremely rare. This ‘Italian Sherry’ has been made in Sardinia since the time of the Phoenicians Francesco Atzori Vernaccia di Oristano DOC 2006 $60 a multifaceted gem, meticulous winemaking translates to Vernaccia di Oristano DOC aromas of dried tangerine peel, tall grasses & marzipan, flavors glisten with sea spray, mint & chamomile- pair with cheeses & seafood for a reflective experience Francesco Atzori Vernaccia di Oristano DOC 1996 $60 hazelnut, dried marigold & polished mahogany unravel to Vernaccia di Oristano DOC reveal flavors of umami, tart pear & a saline, butterscotch finish. -

Prospetto Allegato

PROVINCIA SIGLA CODICE ENTE ENTE IMPORTO ALESSANDRIA AL 1010020090 ARQUATA SCRIVIA 30.595,27 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010020380 CASALE MONFERRATO 48.130,21 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021110 NOVI LIGURE 4.259,97 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021510 SAN SALVATORE MONFERRATO 32.007,64 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021710 TORTONA 33.142,90 ASTI AT 1010070050 ASTI 30.958,41 BIELLA BI 1010960040 BIELLA 25.719,85 BIELLA BI 1010960710 VALDENGO 43.123,61 BIELLA BI 1010960770 VIGLIANO BIELLESE 28.631,34 CUNEO CN 1010270030 ALBA 5.465,46 CUNEO CN 1010270780 CUNEO 64.885,82 NOVARA NO 1010521000 NOVARA 49.198,50 TORINO TO 1010810570 CARIGNANO 15.304,44 TORINO TO 1010810580 CARMAGNOLA 31.889,82 TORINO TO 1010810800 CHIVASSO 32.377,43 TORINO TO 1010810880 COLLEGNO 34.504,29 TORINO TO 1010811180 GRUGLIASCO 29.456,97 TORINO TO 1010812090 RIVAROLO CANAVESE 31.300,33 TORINO TO 1010812550 SETTIMO TORINESE 24.358,84 TORINO TO 1010812620 TORINO 601.191,34 VERBANO-CUSIO-OSSOLA VB 1011020570 PREMOSELLO-CHIOVENDA 15.450,00 VERCELLI VC 1010881360 SERRAVALLE SESIA 30.531,22 BERGAMO BG 1030120200 BARIANO 28.103,81 BERGAMO BG 1030120240 BERGAMO 64.700,58 BERGAMO BG 1030120860 CURNO 30.503,16 BERGAMO BG 1030121220 LOVERE 31.999,29 BERGAMO BG 1030121730 ROMANO DI LOMBARDIA 5.381,30 BRESCIA BS 1030150260 BRESCIA 66.529,42 BRESCIA BS 1030150600 DARFO BOARIO TERME 16.397,84 BRESCIA BS 1030150620 DESENZANO DEL GARDA 7.853,36 COMO CO 1030240720 COMO 88.371,39 COMO CO 1030241380 MASLIANICO 33.163,82 COMO CO 1030241510 MONTORFANO 25.176,14 LECCO LC 1030980130 CALOLZIOCORTE 30.300,43 LECCO LC 1030980420 LECCO 29.380,24 -

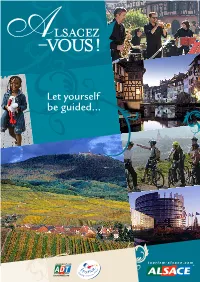

Let Yourself Be Guided…

Let yourself be guided… tourism-alsace.com Contents Introduction 4 to 7 Strasbourg Colmar and Mulhouse Escape into a natural paradise 8 to 17 Discover nature Parks and gardens Well-being and health resorts Wildlife parks and theme parks Hiking Cycle touring, mountain biking, high wire adventure parks, climbing Horseback packing Golf and mini-golf courses Waterborne tourism Water sports, swimming Airborne sports Fishing Winter sports Multi-activity holidays Taste unique local specialities! 18 to 25 Gastronomy, wine seminar, cookery classes Visit the markets Museums of arts and traditions Towns and villages “in bloom”, handicraft Half-timbered houses, traditional Alsatian costume Festivals and traditions Lay siege to history! 26 to 35 Museums Land of fortified castles Memorial sites Religious heritage Practical information about Alsace 36 to 45 Access Accommodation Disabled access Alsace without the car Family holidays in Alsace Weekend and mini-breaks French lessons Festivals, shows and events Tourist Information Offices Tourist trails and routes Map of Alsace The guide to your stay in Alsace Nestling between the Vosges and the Rhine, Alsace is a charming little region with a big reputation. At the crossroads of the Germanic and Latin worlds, it is passionate about its History, yet firmly anchored in modern Europe and open to the world. Rated as among the most beautiful in France, the Alsatian towns and cities win the “Grand prix national de fleurissement”, “Towns in Bloom” prices every year. Through their festivals and their traditions, they have managed to preserve a strong identity based on a particular way of living. World famous cuisine, a remarkably rich history, welcoming and friendly people: in this jewel of a region there really is something for everyone. -

Les Vins Rouges

LES VINS ROUGES Les Vins de CAHORS (A.O.C) 75 cl MAGNUM Le Clos de Gamot à Prayssac – Maison Jouffreau * Clos de Gamot ………………………………………….….….……………….………………………….…..…....2012…………....27 €……….............…..….… * Clos de Gamot ………………………….….……………………….………….………………………….…..…....2011…………....29 €……….............…..….… * Clos de Gamot …………………………………….……….…………………..……….………………….….…....2010…………....35 €……….…...70 € ...….…. * Clos de Gamot ………………………………………..………….………….………………….…………….....….2009……….…………………….….…79 € ….….…. * Clos de Gamot …………………………………….………….……….……………….........................….2005….……..….45 €……….….…90 € ……..…. * Clos de Gamot ………………………………………….…….……….……………….........................….2000….……..….59 €………..….118 € …….…. * Clos de Gamot …………………….………………………….….…………………..………………………..….….1998……….…...65 €..…......................... * Clos de Gamot ………………………………….………….….……………….………………………….…..…....1995…………....75 €……….............…...…… * Clos de Gamot …………………………….……………….…………………..……….………………….….…....1990…………....85 €…………....170 € ..….…. * Clos de Gamot ………………………….………………….………….………..…….…………………….……....1989……….…...89 €………......198 € …..….. * Clos de Gamot ………………………………………..…….…………….…….….….………………………..…….1988………..…..89 €………….…198 € ……... * Clos de Gamot ……………………………..……………………….……….…………………..………….……..…1985……..…….105 €…….………….………...….. * Clos de Gamot « Cuvée des Vignes Centenaires « ……………………………...…………….…..2010….………...55 €………….............…….… * Clos de Gamot « Cuvée des Vignes Centenaires « …………………………………………....…...2005……...…….69 €………....…138 € …..... * Clos de Gamot « Cuvée -

Sub Ambito 01 – Alessandrino Istat Comune 6003

SUB AMBITO 01 – ALESSANDRINO ISTAT COMUNE 6003 ALESSANDRIA 6007 ALTAVILLA MONFERRATO 6013 BASSIGNANA 6015 BERGAMASCO 6019 BORGORATTO ALESSANDRINO 6021 BOSCO MARENGO 6031 CARENTINO 6037 CASAL CERMELLI 6051 CASTELLETTO MONFERRATO 6052 CASTELNUOVO BORMIDA 6054 CASTELSPINA 6061 CONZANO 6068 FELIZZANO 6071 FRASCARO 6075 FRUGAROLO 6076 FUBINE 6078 GAMALERO 6193 LU E CUCCARO MONFERRATO 6091 MASIO 6105 MONTECASTELLO 6122 OVIGLIO 6128 PECETTO DI VALENZA 6129 PIETRA MARAZZI 6141 QUARGNENTO 6142 QUATTORDIO 6145 RIVARONE 6154 SAN SALVATORE MONFERRATO 6161 SEZZADIO 6163 SOLERO 6177 VALENZA SUB AMBITO 02 – CASALESE ISTAT COMUNE 6004 ALFIANO NATTA 6011 BALZOLA 6020 BORGO SAN MARTINO 6023 BOZZOLE 6026 CAMAGNA 6027 CAMINO 6039 CASALE MONFERRATO 6050 CASTELLETTO MERLI 6056 CELLA MONTE 6057 CERESETO 6059 CERRINA MONFERRATO ISTAT COMUNE 6060 CONIOLO 6072 FRASSINELLO MONFERRATO 6073 FRASSINETO PO 6077 GABIANO 6082 GIAROLE 6094 MIRABELLO MONFERRATO 6097 MOMBELLO MONFERRATO 5069 MONCALVO 6099 MONCESTINO 6109 MORANO SUL PO 6113 MURISENGO 6115 OCCIMIANO 6116 ODALENGO GRANDE 6117 ODALENGO PICCOLO 6118 OLIVOLA 6120 OTTIGLIO 6123 OZZANO MONFERRATO 6131 POMARO MONFERRATO 6133 PONTESTURA 6135 PONZANO MONFERRATO 6149 ROSIGNANO MONFERRATO 6150 SALA MONFERRATO 6153 SAN GIORGIO MONFERRATO 6159 SERRALUNGA DI CREA 6164 SOLONGHELLO 6171 TERRUGGIA 6173 TICINETO 6175 TREVILLE 6178 VALMACCA 6179 VIGNALE MONFERRATO 6182 VILLADEATI 6184 VILLAMIROGLIO 6185 VILLANOVA MONFERRATO SUB AMBITO 03 – NOVESE TORTONESE ACQUESE E OVADESE ISTAT COMUNE 6001 ACQUI TERME 6002 ALBERA LIGURE 6005 -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

SWE PIEDMONT Vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER

SWE PIEDMONT vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER ITALY Italy is a spirited, thriving, ancient enigma that unveils, yet hides, many faces. Invading Phoenicians, Greeks, Cathaginians, as well as native Etruscans and Romans left their imprints as did the Saracens, Visigoths, Normans, Austrian and Germans who succeeded them. As one of the world's top industrial nations, Italy offers a unique marriage of past and present, tradition blended with modern technology -- as exemplified by the Banfi winery and vineyard estate in Montalcino. Italy is 760 miles long and approximately 100 miles wide (150 at its widest point), an area of 116,303 square miles -- the combined area of Georgia and Florida. It is subdivided into 20 regions, and inhabited by more than 60 million people. Italy's climate is temperate, as it is surrounded on three sides by the sea, and protected from icy northern winds by the majestic sweep of alpine ranges. Winters are fairly mild, and summers are pleasant and enjoyable. NORTHWESTERN ITALY The northwest sector of Italy includes the greater part of the arc of the Alps and Apennines, from which the land slopes toward the Po River. The area is divided into five regions: Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna. Like the topography, soil and climate, the types of wine produced in these areas vary considerably from one region to another. This part of Italy is extremely prosperous, since it includes the so-called industrial triangle, made up of the cities of Milan, Turin and Genoa, as well as the rich agricultural lands of the Po River and its tributaries. -

Grape Varieties for Indiana

Commercial • HO-221-W Grape Varieties for Indiana COMMERCIAL HORTICULTURE • DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE PURDUE UNIVERSITY COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE • WEST LAFAYETTE, IN Bruce Bordelon Selection of the proper variety is a major factor for fungal diseases than that of Concord (Table 1). Catawba successful grape production in Indiana. Properly match- also experiences foliar injury where ozone pollution ing the variety to the climate of the vineyard site is occurs. This grape is used primarily in white or pink necessary for consistent production of high quality dessert wines, but it is also used for juice production and grapes. Grape varieties fall into one of three groups: fresh market sales. This grape was widely grown in the American, French-American hybrids, and European. Cincinnati area during the mid-1800’s. Within each group are types suited for juice and wine or for fresh consumption. American and French-American Niagara is a floral, strongly labrusca flavored white grape hybrid varieties are suitable for production in Indiana. used for juice, wine, and fresh consumption. It ranks The European, or vinifera varieties, generally lack the below Concord in cold hardiness and ripens somewhat necessary cold hardiness to be successfully grown in earlier. On favorable sites, yields can equal or surpass Indiana except on the very best sites. those of Concord. Acidity is lower than for most other American varieties. The first section of this publication discusses American, French-American hybrids, and European varieties of wine Other American Varieties grapes. The second section discusses seeded and seedless table grape varieties. Included are tables on the best adapted varieties for Indiana and their relative Delaware is an early-ripening red variety with small berries, small clusters, and a mild American flavor.