On the Origin and Development of the Silent Heroes Memorial Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oldenburgische Beiträge Zu Jüdischen Studien Band 10

Oldenburgische Beiträge zu Jüdischen Studien Schriftenreihe des Seminars Jüdische Studien im Fachbereich 3 der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Band 10 Herausgeber Aron Bodenheimer, Michael Daxner Kurt Nemitz, Alfred Paffenholz Friedrich Wißmann (Redaktion) mit dem Vorstand des Seminars Jüdische Studien und dem Dekan des Fachbereichs 3 Mit der Schriftenreihe „Oldenburgische Beiträge zu Jüdischen Studien“ tritt ein junger Forschungszweig der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg an die Öffentlichkeit, der sich eng an den Gegenstand des Studienganges Jüdische Studien anlehnt. Es wird damit der Versuch unternommen, den Beitrag des Judentums zur deutschen und europäischen Kultur bewußt zu machen. Deshalb sind die Studiengebiete aber auch die Forschungsbereiche interdisziplinär ausgerichtet. Es sollen unterschiedliche Themenkomplexe vorgestellt werden, die sich mit Geschichte, Politik und Gesellschaft des Judentums von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart beschäftigen. Ein anderes Hauptgewicht liegt auf der biblischen und nachbiblischen Religion. Ergän- zend sollen aber auch solche Fragen aufgenommen werden, die sich mit jüdischer Kunst, Literatur, Musik, Erziehung und Wissenschaft beschäftigen. Die sehr unterschiedlichen Bereiche sollen sich auch mit regionalen Fragen befassen, soweit sie das Verhältnis der Gesellschaft zur altisraelitischen bzw. Jüdischen Religion berühren oder auch den Antisemitismus behandeln, ganz allgemein über Juden in der Nordwest-Region informieren und hier auch die Vernichtung und Vertreibung in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus behandeln. Viele Informationen darüber sind nach wie vor unberührt in den Akten- beständen der Archive oder auch noch unentdeckt in privaten Sammlungen und auch persönlichen Erinnerungen enthalten. Diese Dokumente sind eng mit den Schicksalen von Personen verbunden. Sie und die Lebensbedingun- gen der jüdischen Familien und Institutionen für die wissenschaftliche Geschichtsschreibung zu erschließen, darin sehen wir eine wichtige Aufgabe, die mit der hier vorgestellten Schriftenreihe voran gebracht werden soll. -

A Study of Early Anabaptism As Minority Religion in German Fiction

Heresy or Ideal Society? A Study of Early Anabaptism as Minority Religion in German Fiction DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ursula Berit Jany Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Advisor Professor Katra A. Byram Professor Anna Grotans Copyright by Ursula Berit Jany 2013 Abstract Anabaptism, a radical reform movement originating during the sixteenth-century European Reformation, sought to attain discipleship to Christ by a separation from the religious and worldly powers of early modern society. In my critical reading of the movement’s representations in German fiction dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, I explore how authors have fictionalized the religious minority, its commitment to particular theological and ethical aspects, its separation from society, and its experience of persecution. As part of my analysis, I trace the early historical development of the group and take inventory of its chief characteristics to observe which of these aspects are selected for portrayal in fictional texts. Within this research framework, my study investigates which social and religious principles drawn from historical accounts and sources influence the minority’s image as an ideal society, on the one hand, and its stigmatization as a heretical and seditious sect, on the other. As a result of this analysis, my study reveals authors’ underlying programmatic aims and ideological convictions cloaked by their literary articulations of conflict-laden encounters between society and the religious minority. -

Germany, Socialism and Nationalism 1373

c07.qxd 3/19/09 9:38 AM Page 1373 International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, ed. Immanuel Ness, Blackwell Publishing, 2009, pp. 1373–1381 Germany, socialism and nationalism 1373 issue of support for the German military effort Germany, socialism precipitated a split within the Social Democratic and nationalism Party. On the eve of the war in July 1914, the SPD’s leadership instructed the party’s Reichstag John M. Cox delegation to vote for the war budget – a decision that was deeply unpopular among the party’s rank Led by Adolf Hitler, the National Socialist, or and file. Nazi, Party took power in Germany in January The war greatly compounded the party’s 1933, promising a “thousand-year empire.” Twelve internal divisions and by 1917 open factions had years later, Germany and most of Europe lay in appeared, competing for control of local organ- ruins, German Nazism having been subdued by izations and of the party’s formidable press the armies of the Soviet Union and the Western apparatus. In April 1917 the left wing formed Allies, led by the United States and Britain. its own party, the Independent Social Demo- But while outside forces were required to bring crats (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei down Hitler’s tyranny, the Nazi dictatorship Deutschlands) (USPD). The USPD was, how- was never free from domestic opposition. The ever, not simply a product of dissension within Third Reich, as the Nazi government was called, the SPD leadership; it also reflected the explosive found its most persistent and numerous enemies social conditions of 1917 resulting from labor in the remnants of Germany’s left-wing parties, protests and a deepening popular abhorrence of which Hitler had ruthlessly suppressed upon the war. -

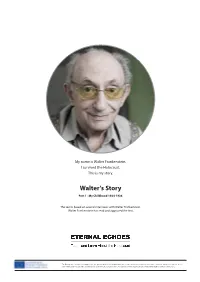

Walter's Story

Walter’s Story My name is Walter Frankenstein. I survived the Holocaust. This is my story. Walter’s Story Part 1 · My Childhood 1924-1936 The text is based on several interviews with Walter Frankenstein. Walter Frankenstein has read and approved the text. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 1 Walter’s Story My Childhood 1924-1936 My Family I come from a small town called Flatow. When I grew up, the town was located in northeastern Germany in what was then known as West Prussia. The entire province became a part of Poland after the Second World War. My father was called Max Frankenstein. His step-parents managed a general store and a tavern in Flatow, and father and his wife later took over the business. They had a son, Manfred, in 1910. A couple of years later, in 1914, they had twins. One of the children died but Martin survived. A while later their mother died from blood poisoning after opening a tin and cutting herself on the lid. My father met my own mother, Martha, in 1923. At the time, she was living with her parents in Braunsberg. She moved to Flatow when they married, and I was born one year later on 30 June 1924. When I was four years old, my father died of pneumonia and heart failure. -

Aktuell Feiert Nr

12. 2017 | No. 100 from and about berlin aAUS UNDk ÜBERt BERLINu ell Jubiläum: aktuell feiert Nr. 100 Anniversary: aktuell celebrates No 100 Filmpremiere: Dritte Generation: „Alte Dame“: „Die Unsichtbaren – My Journey to Berlin 125 Jahre Hertha BSC Wir wollen leben“ Third generation: “Old Lady”: Film première: My journey to Berlin 125 years of Hertha BSC “The Invisible – We Want to Live” INHALT CONTENTS Hertha BSC wird 125 und entdeckt den Mannschaftsarzt Dr. Horwitz wieder Celebrating its 125th anniversary, Hertha BSC remembers its former team doctor Notes of Berlin – eine Hermann Horwitz Hommage an all die 16 Notizen, die Berlin tagtäglich im Stadtbild hinterlässt A homage to all the notes and signs left every day in Berlin’s cityscape „Die Unsichtbaren“ – ein Kinofilm über vier junge Jüdinnen und 58 Juden, die das Dritte Reich mitten in Berlin überlebten “Die Unsichtbaren” – A feature film about four young Jews who survived the Third Reich right in the heart of Berlin 36 Ihre Briefe an die Redaktion Your letters to the editor 48 Berlin übernimmt für ein Jahr die Bundesratspräsidentschaft Berlin is taking on the presidency of the Federal Council for one year 21 Inhalt Contents 2 Editorial Leserbeiträge Editorial Readers’ Contributions 40 Filmpremiere in Deutschland: Schwerpunkt: Jubiläum „Die Unsichtbaren – Wir wollen leben.“ In Focus: Anniversary Film première in Germany: “The Invisible – We Want to Live” 4 Masal tow! 42 Trotz allem kann ich stolz sagen: Mazal tov! „Ich bin ein Berliner!“ 8 „Liebe ehemalige Mitbürger …“ Despite it all, I can proudly say “Dear former fellow-citizens …” “I am a Berliner!” 12 „Ein Stück Heimat“ – der Kalender 44 My Journey to Berlin: The Presence of History The calendar – “A bit of Heimat” 45 Erinnerungen 14 In eigener Sache: aktuell im neuen Gewand Memories A word from the editor: aktuell in makeover 46 „Berlin bleibt Berlin!“ mode 48 Leserbriefe Berliner Ereignisse Letters to the Editor Life in Berlin 16 „Dr. -

German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 the Facts and the Problems © Beim Autor Und Bei Der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand

Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand German Resistance Memorial Center German Resistance 1933 – 1945 Arnold Paucker German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 The Facts and the Problems © beim Autor und bei der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Redaktion Dr. Johannes Tuchel Taina Sivonen Mitarbeit Ute Stiepani Translated from the German by Deborah Cohen, with the exception of the words to the songs: ‘Song of the International Brigades’ and ‘The Thaelmann Column’, which appear in their official English-language versions, and the excerpt from Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s poem ‘Beherzigung’, which was translated into English by Arnold Paucker. Grundlayout Atelier Prof. Hans Peter Hoch Baltmannsweiler Layout Karl-Heinz Lehmann Birkenwerder Herstellung allprintmedia GmbH Berlin Titelbild Gruppe Walter Sacks im „Ring“, dreißiger Jahre. V. l. n. r.: Herbert Budzislawski, Jacques Littmann, Regine Gänzel, Horst Heidemann, Gerd Meyer. Privatbesitz. This English text is based on the enlarged and amended German edition of 2003 which was published under the same title. Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2005 ISSN 0935 - 9702 ISBN 3-926082-20-8 Arnold Paucker German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 The Facts and the Problems Introduction The present narrative first appeared fifteen years ago, in a much-abbreviated form and under a slightly different title.1 It was based on a lecture I had given in 1988, on the occasion of the opening of a section devoted to ‘Jews in the Resistance’ at the Berlin Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand, an event that coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the Kristallnacht pogrom. As the Leo Baeck Institute in London had for many years been occupied with the problem, representation and analysis of Jewish self-defence and Jewish resistance, I had been invited to speak at this ceremony. -

Provenienzforschung an Der Kunsthalle Zu Kiel Gemälde Und Skulpturen

Provenienzforschung an der Kunsthalle zu Kiel Gemälde und Skulpturen Verfasser: Dr. Kai Hohenfeld Projektleitung Provenienzforschung Kunsthalle zu Kiel: Dr. Annette Weisner Tel.: +49 431 880-5780 E-Mail: [email protected] Direktorin Kunsthalle zu Kiel: Dr. Anette Hüsch gefördert vom Deutschen Zentrum Kulturgutverluste Kunsthalle zu Kiel Christian-Albrechts-Universität Düsternbrooker Weg 1 24105 Kiel Forschungsstand: 31.10.2017 Provenienzforschung Kunsthalle zu Kiel, Christian-Albrechts-Universität Verfasser: Dr. Kai Hohenfeld Projektleitung: Dr. Annette Weisner ([email protected]) Forschungsstand: 31.10.2017 Inhalt Provenienzforschung an der Kunsthalle zu Kiel – Gemälde und Skulpturen... 3 Künstlerindex............................................................ 6 Als kriegsbedingt verlagertes Kulturgut (sog. Beutekunst) identifiziert.. und zurückgegeben: Vasilij Dmitrievič Polenov, Inv. 908 ............... 7 Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, Inv. 477, erworben 1936 .............. 16 Carl Trost, Inv. 480, erworben 1936 .................................. 24 Friedrich Loos, Inv. 498, erworben 1938 .............................. 28 Christian Sell, Inv. 513 und 514, erworben 1940 ...................... 32 Philipp Harth, Inv. Pl 47, erworben 1942 ............................. 35 Johann Heinrich Hintze, Inv. 544, erworben 1948 ...................... 37 Alexander Kanoldt, Inv. 545, erworben 1948 ........................... 39 Ernst Barlach, Inv. Pl 49, erworben 1949 ............................. 41 Lovis Corinth, Inv. 548, erworben -

Überleben Im Untergrund Reihe Solidarität Und Hilfe Rettungsversuche Für Juden Vor Der Verfolgung Und Vernichtung Unter Nationalsozialistischer Herrschaft

Beate Kosmala Claudia Schoppmann (Hrsg.) Überleben im Untergrund Reihe Solidarität und Hilfe Rettungsversuche für Juden vor der Verfolgung und Vernichtung unter nationalsozialistischer Herrschaft Herausgegeben im Auftrag des Zentrums für Antisemitismusforschung von Wolfgang Benz Band 5 Beate Kosmala · Claudia Schoppmann (Hrsg.) Überleben im Untergrund Hilfe für Juden in Deutschland 1941–1945 Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme: Überleben im Untergrund : Hilfe für Juden in Deutschland 1941–1945 / Beate Kosmala ; Claudia Schoppmann (Hrsg.). – Berlin : Metropol, 2002 (Reihe Solidarität und Hilfe ; Bd. 5) ISBN 3-932482-86-7 Gefördert von der Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung © 2002 Metropol Verlag Kurfürstenstr. 135 D–10785 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: Primus Solvero, Berlin Inhalt Wolfgang Benz Solidarität mit Juden während der NS-Zeit Eine Einführung 9 Beate Kosmala · Claudia Schoppmann Überleben im Untergrund Zwischenbilanz eines Forschungsprojekts 17 Karl-Heinz Reuband Zwischen Ignoranz, Wissen und Nicht-glauben-Wollen Gerüchte über den Holocaust und ihre Diffusionsbedingungen in der deutschen Bevölkerung 33 David Bankier Was wußten die Deutschen vom Holocaust? 63 Inge Marszolek Denunziation im Dritten Reich Kommunikationsformen und Verhaltensweisen 89 Claudia Schoppmann Rettung von Juden: ein kaum beachteter Widerstand von Frauen 109 Ursula Büttner Die anderen Christen Ihr Einsatz für verfolgte Juden und „Nichtarier“ im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland 127 Kurt Schilde Grenzüberschreitende -

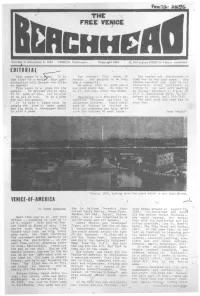

Rick Davidson

Number 1, December 1, 1968 VENICE, California Copyright 1968 10, 000 copies FREE to Venice residents x EDITORIAL v This paper is a p>oem. It is Our subject this issue is Any reader cah contribute in the first of a series. Your par Venice. Our purpose is to ere- some way to our next poem. Any ticipation will decide how often ate a community. Venice resident may join-in our we appear. We would like to give you a collective staff decisions by This paper is a poem for the new poem every day. We hope to rowing to our next work meetin people. We decided not- to sell do it, for now, every two weeks. on Sunday, December 8, 8 p.m. à*t 1727 W. Washington Blvd. To vol it to some of you, but to give * • it to all of you. It is a poem Beachhaa.d is a non-profit en unteer by phone, call 399-7681. .for all the people. terprise produced entirely by The next poem you read may be It is also a paper made -by volunteer workers. Every resi^ your own. people who love to make poems dent of Venice is invited to and dig doing a newspaper which join our endeavor and help tcT de is also a poem. cide the outcome of each issue. Free Venice1. Venice, 1924, looking down the canal which is now Main Street. VENICE-OF-AMERICA ^ by JANE GORDON the La Ballona Township (now they broke ground on August 15. called Santa Monica, Ocean Park, 1904. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Acknowledgments vii List of Abbreviations ix Introduction 1 Varieties of Anti-Nazi Resistance 4 Sources of Resistance: Jewish, Youth, Leftist Movements 6 Chapter 1: Assimilation and Alienation: The Origins and Growth of German-Jewish Youth Movements 11 The Jewish Experience in Germany 12 Assimilation: An Uneasy Balance 14 German and German-Jewish Youth Groups, 1900-1933 15 German-Jewish Youth Groups, 1933-1939 19 Socialism and Jewish Youth Politics 22 Chapter 2: Neither Hitler Nor Stalin: Resistance by Dissident Communists and Left-Wing Socialists 27 End of Weimar Democracy and the Emergence of Left Splinter Groups 33 The “Org” (Neu Beginnen) 34 Decline and Demise of the Org 40 The Left Opposition in Berlin 41 Clandestine Activities of the Left Oppositionists 44 Jews in Socialism’s Left Wing 47 Chapter 3: Repression and Revival: Contradictions of the Communist-led Resistance in Berlin 57 Initial Setbacks and Underground Organization 58 Stalin-Hitler Treaty: Disorientation and Accommodation 61 German Marxism and the “Jewish Question” 63 Jews in Berlin’s Communist-led Resistance 67 Communist Politics: Weapon or Obstacle? 73 vi Jewish, Leftist, and Youth Dissidence in Nazi Germany Chapter 4: “Thinking for Themselves”: The Herbert Baum Groups 81 Herbert Baum: Origins and Influences 83 Baum and the Structure of His Groups, 1933-1942 86 Toward Anti-Nazi Action 91 Chapter 5: “We Have Gone on the Offensive”: Education and Other Subversive Activities Under Dictatorship 95 Persecution and Perseverance 96 Heimabende: Underground -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungliste 4. Quartal 2000

Geschichte Neuerwerbungliste 4. Quartal 2000 Geschichte: Einführungen ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie.......................................................................................................... 2 Historische Hilfswissenschaften.............................................................................................................................. 5 Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie ................................................................................ 8 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege ..................................... 17 Alte Geschichte ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit .............................................................................................. 32 Deutsche Geschichte ............................................................................................................................................. 37 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte..................................................................................................... 46 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns, Tschechiens und der Slowakei................................................... 52 Geschichte Skandinaviens -

The Fate of Young Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany

Walter Laqueur: Generation Exodus page A “This latest valuable addition to Walter Laqueur’s insightful and extensive chron- icle of European Jewry’s fate in the twentieth century is an exceedingly well- crafted and fascinating collective biography of the younger generation of Jews: how they lived under the heels of the Nazis, the various routes of escape they found, and how they were received and ultimately made their mark in the lands of their refuge. It is a remarkable story, lucidly told, refusing to relinquish its hold on the reader.” —Rabbi Alexander M. Schindler, President emeritus, Union of American Hebrew Congregations “Picture that generation, barely old enough to flee for their lives, and too young to offer any evident value to a world loath to give them shelter. Yet their achieve- ments in country after country far surpassed the rational expectations of conven- tional wisdom. What lessons does this story hold for future generations? Thanks to Walter Laqueur’s thought-provoking biography, we have a chance to find out.” —Arno Penzias, Nobel Laureate “Generation Exodus documents the extraordinary experiences and attitudes of those young Austrian and German Jews who were forced by the Nazis to emigrate or to flee for their lives into a largely unknown outside world. In most cases they left behind family members who would be devoured by the infernal machines of the Holocaust. Yet by and large, some overcoming great obstacles, some with the help of caring relatives or friends, or of strangers, they became valuable members of their adopted homelands. Their contributions belie their small numbers.