UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Do Young Children Acquire Case Marking?

INVESTIGATING FINNISH-SPEAKING CHILDREN’S NOUN MORPHOLOGY: HOW DO YOUNG CHILDREN ACQUIRE CASE MARKING? Thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences 2015 HENNA PAULIINA LEMETYINEN SCHOOL OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 8 DECLARATION .......................................................................................................................... 9 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT .......................................................................................................... 9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: General introduction to language acquisition research ...................................... 11 1.1. Generativist approaches to child language............................................................ 11 1.2. Usage-based approaches to child language........................................................... 14 1.3. The acquisition of morphology ............................................................................. -

Morphological Causatives Are Voice Over Voice

Morphological causatives are Voice over Voice Yining Nie New York University Abstract Causative morphology has been associated with either the introduction of an event of causation or the introduction of a causer argument. However, morphological causatives are mono-eventive, casting doubt on the notion that causatives fundamentally add a causing event. On the other hand, in some languages the causative morpheme is closer to the verb root than would be expected if the causative head is responsible for introducing the causer. Drawing on evidence primarily from Tagalog and Halkomelem, I argue that the syntactic configuration for morphological causatives involves Voice over Voice, and that languages differ in whether their ‘causative marker’ spells out the higher Voice, the lower Voice or both. Keywords: causative, Voice, argument structure, morpheme order, typology, Tagalog 1. Introduction Syntactic approaches to causatives generally fall into one of two camps. The first view builds on the discovery that causatives may semantically consist of multiple (sub)events (Jackendoff 1972, Dowty 1979, Parsons 1990, Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1994, a.o.). Consider the following English causative–anticausative pair. The anticausative in (1a) consists of an event of change of state, schematised in (1b). The causative in (2a) involves the same change of state plus an additional layer of semantics that conveys how that change of state is brought about (2b). (1) a. The stick broke. b. [ BECOME [ stick STATE(broken) ]] (2) a. Pat broke the stick. b. [ Pat CAUSE [ BECOME [ stick STATE(broken) ]]] Word Structure 13.1 (2020): 102–126 DOI: 10.3366/word.2020.0161 © Edinburgh University Press www.euppublishing.com/word MORPHOLOGICAL CAUSATIVES ARE VOICE OVER VOICE 103 Several linguists have proposed that the semantic CAUSE and BECOME components of the causative are encoded as independent lexical verbal heads in the syntax (Harley 1995, Cuervo 2003, Folli & Harley 2005, Pylkkänen 2008, a.o.). -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

The Finnish Noun Phrase

Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere Corso di Laurea Specialistica in Scienze del Linguaggio The Finnish Noun Phrase Relatore: Prof.ssa Giuliana Giusti Correlatore: Prof. Guglielmo Cinque Laureanda: Lena Dal Pozzo Matricola: 803546 ANNO ACCADEMICO: 2006/2007 A mia madre Table of contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………….…….…… III Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………........ V Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………VII 1. Word order in Finnish …………………………………………………………………1 1.1 The order of constituents in the clause …………………………………………...2 1.2 Word order and interpretation .......……………………………………………… 8 1.3 The order of constituents in the Nominal Expression ………………………… 11 1.3.1. Determiners and Possessors …………………………………………………12 1.3.2. Adjectives and other modifiers …………………………………………..… 17 1.3.2.1 Adjectival hierarchy…………………………………………………………23 1.3.2.2 Predicative structures and complements …………………………………26 1.3.3 Relative clauses …………………………………………………………….... 28 1.4 Conclusions ............……………………………………………………………. 30 2. Thematic relations in nominal expressions ……………………………………….. 32 2.1 Observations on Argument Structure ………………………………….……. 32 2.1.1 Result and Event nouns…………………………………………………… 36 2.2 Transitive nouns ………………………………………………………………... 38 2.2.1 Compound nouns ……………….……………………………………... 40 2.2.2 Intransitive nouns derived from transitive verbs …………………… 41 2.3 Passive nouns …………………………………………………………………… 42 2.4 Psychological predicates ……………………………………………………….. 46 2.4.1 Psych verbs ………………………………………………………………. -

The Esperantist Background of René De Saussure's Work

Chapter 1 The Esperantist background of René de Saussure’s work Marc van Oostendorp Radboud University and The Meertens Institute ené de Saussure was arguably more an esperantist than a linguist – R somebody who was primarily inspired by his enthusiasm for the language of L. L. Zamenhof, and the hope he thought it presented for the world. His in- terest in general linguistics seems to have stemmed from his wish to show that the structure of Esperanto was better than that of its competitors, and thatit reflected the ways languages work in general. Saussure became involved in the Esperanto movement around 1906, appar- ently because his brother Ferdinand had asked him to participate in an inter- national Esperanto conference in Geneva; Ferdinand himself did not want to go because he did not want to become “compromised” (Künzli 2001). René be- came heavily involved in the movement, as an editor of the Internacia Scienca Re- vuo (International Science Review) and the national journal Svisa Espero (Swiss Hope), as well as a member of the Akademio de Esperanto, the Academy of Es- peranto that was and is responsible for the protection of the norms of the lan- guage. Among historians of the Esperanto movement, he is also still known as the inventor of the spesmilo, which was supposed to become an international currency among Esperantists (Garvía 2015). At the time, the interest in issues of artificial language solutions to perceived problems in international communication was more widespread in scholarly cir- cles than it is today. In the western world, German was often used as a language of e.g. -

Affectedness Constructions: How Languages Indicate Positive and Negative Events

Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith B.S. (Doshisha Women’s College) 1987 M.A. (San Jose State University) 1995 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser Professor Soteria Svorou Professor Charles J. Fillmore Professor Yoko Hasegawa Fall 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events Copyright 2005 by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Affectedness constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Chair This dissertation is a cross-linguistic study of what I call “affectedness constructions” (ACs) that express the notions of benefit and adversity. Since there is little research dealing with both benefactives and adversatives at the same time, the main goal of this dissertation is to establish AC as a grammatical category. First, many instances of ACs in the world are provided to show both the diversity of ACs and the consistent patterns among them. In some languages, a single construction indicates either benefit or adversity, depending on the context, while in others there is one or more individual benefactive and/or adversative construction(s). Since the event types that ACs indicate appear limited, I categorize the constructions by event type and discuss Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin

1 Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief introduction to the Japanese language, and natural language processing (NLP) research on Japanese. For a more complete but accessible description of the Japanese language, we refer the reader to Shibatani (1990), Backhouse (1993), Tsujimura (2006), Yamaguchi (2007), and Iwasaki (2013). 1 A Basic Introduction to the Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan, and belongs to the Japanese language family (Gordon, Jr., 2005).1 The first-language speaker pop- ulation of Japanese is around 120 million, based almost exclusively in Japan. The official version of Japanese, e.g. used in official settings andby the media, is called hyōjuNgo “standard language”, but Japanese also has a large number of distinctive regional dialects. Other than lexical distinctions, common features distinguishing Japanese dialects are case markers, discourse connectives and verb endings (Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyujyo, 1989–2006). 1There are a number of other languages in the Japanese language family of Ryukyuan type, spoken in the islands of Okinawa. Other languages native to Japan are Ainu (an isolated language spoken in northern Japan, and now almost extinct: Shibatani (1990)) and Japanese Sign Language. Readings in Japanese Natural Language Processing. Francis Bond, Timothy Baldwin, Kentaro Inui, Shun Ishizaki, Hiroshi Nakagawa and Akira Shimazu (eds.). Copyright © 2016, CSLI Publications. 1 Preview 2 / Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin 2 The Sound System Japanese has a relatively simple sound system, made up of 5 vowel phonemes (/a/,2 /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/), 9 unvoiced consonant phonemes (/k/, /s/,3 /t/,4 /n/, /h/,5 /m/, /j/, /ó/ and /w/), 4 voiced conso- nants (/g/, /z/,6 /d/ 7 and /b/), and one semi-voiced consonant (/p/). -

Conjugation Class and Transitivity in Kipsigis Maria Kouneli, University of Leipzig [email protected]

April 22nd, 2021 Workshop on theme vowels in V(P) structure and beyond University of Graz Conjugation class and transitivity in Kipsigis Maria Kouneli, University of Leipzig [email protected] 1 Introduction • Research on conjugation classes and theme vowels has mostly focused on Indo- European languages, even though they are not restricted to this language family (see Oltra-Massuet 2020 for an overview). • The goal of this talk is to investigate the properties of inflectional classes in Kip- sigis, a Nilotic language spoken in Kenya: – in the nominal domain, the language possesses a variety of thematic suffixes with many similarities to Romance theme vowels; the theory in Oltra-Massuet & Arregi (2005) can account for their distribution – in the verbal domain, the language has two conjugation classes, which I will argue spell out little v, and are closely related to argument structure, espe- cially the causative alternation • Recent syntactic approaches to the causative alternation treat it as a Voice alterna- tion: – the causative and anticausative variants have the same vP (event) layer, but differ in the presence vs. absence of an external argument-introducing Voice head (e.g., Marantz 2013, Alexiadou et al. 2015, Wood 2015, Kastner 2016, 2017, 2018, Wood & Marantz 2017, Nie 2020, Tyler 2020). (1) a. The cup broke. Anticausative b. Mary broke the cup. Causative • I show that the causative alternation in Kipsigis cannot be (just) a Voice alterna- tion: (in)transitivity in the language is calculated at the little v level for most verbs that participate in the alternation. Roadmap: 2: Inflectional classes in Kipsigis 3: Theories of the causative alternation (with a focus on morphology) 4: More on the causative alternation in Kipsigis 5: The challenge for Voice theories 6: Conclusion 1 Maria Kouneli Theme vowels in VP structure 2 Inflectional classes in Kipsigis 2.1 Language background • Kipsigis is the major variety of Kalenjin, a dialect cluster of the Southern Nilotic branch of Nilo-Saharan. -

Towards Possessive Sentences Classification in English – the Preliminary Study

Linguistics and Literature Studies 1(1): 37-42, 2013 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2013.010106 Towards Possessive Sentences Classification in English – The Preliminary Study V.A. Yatsko*, T.S. Yatsko Katanov State University of Khakasia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract The paper focuses on the structure of puck; also: an instance of having such control (as in football); predicative possessive constructions described in terms of 2) something owned, occupied, or controlled: property [4]. semantic features distinguished within scope of predication Christian Lehmann [5 p. 7] notes that control of the analysis, viz. causative, agentive, inchoative, egressive, possessum by the possessor is the default assumption and continuative, and stative features. Features that are in insofar the default interpretation of the possessive relation. complementary distribution yield contaminated forms of Such an interpretation excludes from the present analysis possessive constructions: inchoative-causative, sentences, in which X and Y are non-human, see (1) below, as inchoative-agentive, egressive-causative, egressive-agentive, continuative-causative, continuative-agentive. Causative well as sentences expressing family relations: *Nichols has a possessive constructions are taken to be basic since their brother, but he is not a twin. According to a broader structure corresponds to the structure of the prototypical approach possession is treated as a relational concept that situation while the other ones are derived from them by covers relations between persons and their body parts and omission of appropriate semantic features. The structure of products, between persons and their kin, between persons causative possessive sentences is described in terms of and their material belongings, between persons and things componential analysis. -

The Influence of Animacy and Context on Word Order Processing: Neurophysiological Evidence from Mandarin Chinese

Impressum Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, 2011 Diese Arbeit ist unter folgender Creative Commons-Lizenz lizenziert: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Druck: Sächsisches Druck- und Verlagshaus Direct World, Dresden ISBN 978-3-941504-13-4 The Influence of Animacy and Context on Word Order Processing: Neurophysiological Evidence from Mandarin Chinese Von der Philologischen Fakultät der Universität Leipzig genehmigte DISSERTATION Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae Dr. Phil. vorgelegt von Luming Wang geboren am 16. Februar 1981 in Zhoushan, China Dekan: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Lörscher Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Balthasar Bickel Prof. Dr. Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky Prof. Dr. Kaoru Horie For my mother tongue, one of the many languages in this world. Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the support and friendship of many people. If life is like online sentence processing in the sense that one must make a decision even without being sure of where it will lead, those people are definitely “prominent” characters that have greatly influenced my decisions, especially when I was experiencing “ambiguities” during different periods. I would like to thank them in chronological order. I thank my parents for giving me the initial processing preference, which has driven me to become closer to those things and people that I like, but unexpectedly lead me farther from them. I thank them from the bottom of my heart for their continuing selfless love. I am lucky for having been a student of Prof. Kaoru Horie and Prashant Pardesh during my MA studies at Tohoku University in Japan. -

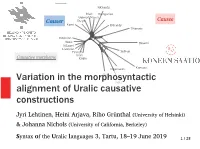

Variation in the Morphosyntactic Alignment of Uralic Causative

0.1 NKhanty Mari Hungarian Udmurt Mansi Causer Erzya Causee Komi EKhanty TNenets Estonian Votic SSaami NSaami Livonian Finnish Selkup Inari Causative morpheme Kildin Kamass Nganasan Variation in the morphosyntacticSEst Veps alignment of Uralic causative constructions Jyri Lehtinen, Heini Arjava, Riho Grünthal (University of Helsinki) & Johanna Nichols (University of California, Berkeley) Syntax of the Uralic languages 3, Tartu, 18–19 June 2019 1 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● Extension into the Uralic languages of the approach described in Nichols et al. (2004) – Lexical valence orientation: Transitivizing vs. detransitivizing (or causativizing vs. decausativizing) languages – In addition, phylogenetic models of Uralic language relationships – Phylogenies taking into account both valence orientation (grammar) and origin of relevant forms (etymology) 2 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● 22 Uralic language varieties: – South Sámi, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, Kildin Sámi – Finnish, Veps, Votic, Estonian, Southern Estonian, Livonian – Erzya – Meadow Mari – Udmurt, Komi-Zyrian – Hungarian, Northern Mansi, Eastern Khanty, Northern Khanty – Tundra Nenets, Nganasan, Kamass, Selkup 3 / 28 Alternation in animate verbs ● For animate verbs, all surveyed languages are predominantly causativizing – e.g. ’eat’ / ’feed’: North Sámi borrat / borahit; Estonian sööma / söötma; Northern Mansi tēŋkwe / tittuŋkwe; Hungarian eszik / etet ● Little decaus., much caus.: North Sámi, S Estonian, Mari, Samoyed; much decaus., little caus.: Kildin Sámi, Livonian, -

CAUSATIVE CONJUGATION Lntroduction the Grammatical Category "Causative" Is Semantically Definable As a "Macrosituation" Consisting of Two "Microsituations"

CHAPTER FOUR THE SEMITIC CAUSATIVE CONJUGATION lntroduction The grammatical category "causative" is semantically definable as a "macrosituation" consisting of two "microsituations". A microsituation consists of two constants: thema and rhema or subject and predicate. When two such microsituations are combined so that one is considered the cause of the other, we speak of a causative macrosituation.' It is obvious that there are many ways of realizing this semantic structure on the expression Ievel of a language. We are here concerned with one of these devices, viz. the causative verb. Such a verb represents two elements of the causative macrosituation: the predicates of both the causing and the caused microsituations. The causative macrosituation Iooks like this: the fiddler cause the girl dance s p S* P* A characteristic of the situation underlying the causative verb is that the predicate of the causing situation is empty of all semantic content except the feature causativity. 2 In transformational terms, the surface structure can be described as the result of predicate raising of P* and objectivization of S *. the fiddler cause-dance the girl In many languages, predicate raising does not usually occur. Instead P is realized as a separate verb 'to cause'. This is also found in Semitic although we mostly have causative verbs including both P and P*. 3 Syntactically such verbs are characterized by valency increasing: a monovalent verb ( = intransitive) is made bivalent by the addition of one actant, viz. the causator ( = S), while the former first actant (S*) is moved 1 For the following analysis see especially Nedyalkov/Silnitzky, 1 f.